For R.I.’s Disenfranchised Populations, Their Next-Door Neighbor is Often Pollution

Low-income housing, assisted-living facilities, and schools in these neighborhoods built on contaminated ground

June 13, 2022

PROVIDENCE — Miguel Sanchez’s response to the question was less an answer and more of an example. When asked what environmental justice means to him, the Olneyville resident spoke about the 2020 dumping of contaminated material in his neighborhood, where 75% of the residents are people of color.

“If that happened in the East Side of Providence it would have been gone the next day,” said Sanchez, a member of the Olneyville Neighborhood Association. “It’s the example I like to bring to people’s attention — just as matter of fact of how that happened and how long it took [to remove the piles]. I don’t think people were held accountable.”

Olneyville’s health and well-being were not priorities when the state agency that rebuilt the 6-10 Connector using 1950s specs allowed the project’s primary developer to dump contaminated dirt in one of the city’s two environmental justice neighborhoods. (The other is South Providence.)

The illegal dumping wasn’t made public by the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT), but by heavy-equipment operators who complained of excessive dust at worksites throughout the extensive construction site.

When their pleas for help were not addressed by either the developer or state agencies — even though RIDOT was aware of the problems associated with the trucked-in fill — the union for the heavy-equipment operators launched its own investigation. A test paid for by the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 57 found the material contained two times the acceptable levels of carcinogenic aromatic hydrocarbons and four times the acceptable levels of benzo(a)pyrene, another carcinogen.

The union’s findings came to light in mid-September 2020.

RIDOT and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) had relied on fill tests performed by an independent firm that was selected and paid by the project’s primary construction company, Barletta Heavy Division Inc. The Massachusetts-based company also told RIDOT that all of the suspect fill came from the MBTA Orient Heights Station redevelopment project in East Boston, which the Canton contractor was also overseeing.

A Local 57 employee, however, followed dump trucks and monitored radio discussions between drivers to determine that at least some of the contaminated 6-10 Connector fill was hauled in from railway transit projects in Pawtucket/Central Falls and Jamaica Plain, Mass.

A test of material in 2019 at the site for the Pawtucket/Central Falls commuter rail station and bus hub project found excessive levels of arsenic and toxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. RIDOT and DEM eventually confirmed that some of the illegally dumped material came from the Pawtucket/Central Falls bus and rail station construction site, another project led by the 6-10 Connector’s primary contractor.

After receiving contradictory results from the contractor and the union, a test conducted by a RIDOT consultant and DEM found the material dumped in Olneyville to be contaminated.

The contractor was ordered to remove a 2,500-cubic-yard pile next to a ramp for Plainfield Pike, another pile of about 1,600 cubic yards worth of hazardous fill, and any other toxic material dumped at the construction site.

After the contractor failed to act in a timely manner, RIDOT quietly issued a formal notice Aug. 3, 2020, to the company ordering the toxic piles be removed by Aug. 17.

The deadline passed without any action taken. The state didn’t really seem to care. RIDOT’s director downplayed the toxicity of the material during a Sept. 10 WPRO radio interview, saying the material that had been dumped near Olneyville homes was clean.

Six days later, and after Local 57’s concerns had been made public, RIDOT issued a press release that noted the fill “showed levels of some contaminants above regulatory thresholds. As a result, DEM and RIDOT agreed that the soil should be removed.”

By early November 2020, the contaminated Olneyville piles remained. ecoRI News reached out to RIDOT and other state agencies to find out what was going on.

RIDOT referred questions about the matter to State Police and the attorney general’s office. State Police declined to discuss the matter and directed inquiries back to RIDOT. The Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH) said it couldn’t discuss a matter that is being actively investigated, but noted the agency is looking into the matter with DEM.

“I apologize that we are not at liberty to go into all the details of the logistics of the piles,” RIDOT’s communications director wrote in a Nov. 5 email. “We are as frustrated as I am sure you are about our inability to clarify facts and misstatements. The Director’s and our hands are tied right now but we hope to be able to clear up a number of allegations in the near future. When the Director is ready and able to talk about this entire sequence of events, we will be sure to reach out to you. This should be shortly.”

ecoRI News never heard back, and the RIDOT director has never spoken about the “sequence of events.” The investigation, which allegedly included the U.S. attorney’s office for the District of Rhode Island, has yet to file any charges or even issue a statement.

In a June 8 email to ecoRI News, a spokesperson for the attorney general’s office wrote, “Our investigation is ongoing. I will be able to follow up with you when we have an update.”

By the end of 2020, some six months after the contaminated fill was dumped on Olneyville, the contaminated material was finally removed from a community where 64% of the population is Latino and 11% is Black.

The fact that underprivileged communities are in some of the most polluted environments in the United States is no coincidence. These neighborhoods are often chosen for bus terminals, fossil fuel infrastructure, chemical plants, incinerators, landfills, and contaminated fill because business interests and the lawmakers they financially support know it is difficult for the residents who live in these communities to object. They can’t afford to hire an attorney to protect their interests. They may speak English as a second language. They lack powerful connections.

Industrial disease

A polluted river winding its way through different neighborhoods diminishes public enjoyment and residents’ well-being, even if many of the people living and playing along its banks don’t realize it and those in power do.

The nearly 20-mile-long Woonasquatucket River, since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution 260 years ago, has dealt with all kinds of contamination. But before the pollution deluge became too much for Mother Nature to overcome, Merino and Donigian parks in Olneyville during the later years of the 1800s were destinations for people looking to enjoy a swim, a picnic, and some green space.

But by the end of the aughts a century and a half later, the popular parks and the river that flows by them were little more than dumping grounds, trashed with tires, shopping carts, and a disgusting assortment of other debris.

The more pressing concern, however, was the decades of industrial toxins that had built up in the Woonasquatucket River’s sediment, making it unswimmable and the fish in it inedible.

Warning people of these dangers, however, was never a priority for those in the know. By the end of the 19th century, for instance, municipal and state officials should have advised swimmers against taking a dip in the Woonasquatucket River, especially in its lower reaches.

While factories, mills, and other industry used the urban river as a power source, these operations also used it as a dumpster and a toilet for waste.

Among the contaminants of the Industrial Revolution that made their way into the Woonasquatucket River were: trace amounts of heavy metals such as cadmium and zinc used to set dyes on fabrics, and copper, iron, pewter, and tin used to make tools and parts; volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds, such as carcinogens hexachlorophene, perchloroethylene (PCE), and trichloroethylene (TCE), used to clean machinery and tools; and pesticides containing arsenic and mercury that were used to prevent insect damage to cotton and wool.

Over time one site along the banks of the Woonasquatucket River above all others became the biggest concern for those living downstream, mainly because of unregulated use, storage, and disposal of hazardous substances.

From 1943 to 1971, the Centredale Manor site on Smith Street in North Providence was used by two companies for chemical manufacturing and for drum recycling. Before that, from 1921-1940, the site was occupied by the Centredale Worsted Mill and then the Olneyville Wool Combing Co.

In the early 1970s, all the buildings on the contaminated site — by this time the property’s history of use and the Woonasquatucket River’s polluted past were well known — were demolished to make way for assisted-living apartments for seniors and low-income people (Centredale Manor) and an affordable housing community (Brook Village).

But construction of the Brook Village apartments was halted in 1977, when DOH responded to complaints of noxious fumes, and found more than 50 abandoned chemical drums. In the early ’80s, more drums, containing acid, solvents and ink wastes, were found at the site by DEM.

Elevated levels of dioxin and furan — some of the most toxic chemicals known to science — polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), semi-VOCs, and heavy metals were eventually detected in the soil, sediment, groundwater, and surface water at the site.

Dioxin contamination — e.g., 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin was released into the river for years as a byproduct of the production of hexachlorophene — in fish collected from the Woonasquatucket River was first documented in 1996. DOH and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a fish consumption advisory for sections of the Woonasquatucket River. Mercury and PCBs were also found in the eels and sunfish tested.

Dioxin, though, continues to be the substance of concern when it comes to the Woonasquatucket River, according to Michael Byrns, a DOH risk assessment toxicologist.

DOH still advises against eating fish caught below the Smithfield-Johnston line.

Despite all the work completed to remediate the Centredale Manor Superfund site and the health of the river that bore the brunt of its pollution, DOH also recommends people not swim or wade in the Woonasquatucket. Paddlers are advised to shower after spending time on the river.

State officials and Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council staff and volunteers have put a lot of time and effort into cleaning the river, but Byrns said the day when recreational activities in the river and eating fish taken from it are safe is still a ways away.

The Woonasquatucket River is a mainstay on DEM’s list of impaired waters. Stormwater outfalls, rushing polluted runoff from parking lots, roofs, and other impervious surfaces, dot the river’s banks.

The EPA, DOH, and community groups have used multilingual outreach programs to inform people of the potential health risks posed by the river and the toxic-laden largemouth bass, American eels, and white suckers swimming in it. EPA representatives have knocked on doors to inform residents that it’s not safe to fish or swim in the Woonasquatucket River. “Don’t Eat The Fish” signs, in both English and Spanish, have been posted.

These efforts, however, haven’t been enough. Weather-beaten and vandalized signs haven’t been replaced. People move. The river’s contaminated fish still provide food for families hungry now. Officials know people are still eating fish caught from the Woonasquatucket River.

During an April 12 online environmental health risk assessment update on the Woonasquatucket River by DOH, state officials noted, despite 24 years of outreach, that the public still needs to be better educated about the river’s health risks. DOH plans to conduct surveys this spring and summer to find out how many people are eating fish or other animals they catch in the Woonasquatucket River and its watershed.

Eugenia Marks, a local environmental champion and the retired senior director of policy for the Audubon Society of Rhode Island, recalled speaking with a child catching reptiles from the murky waters of the Woonasquatucket River who told her the turtles help feed his family.

Melissa Guillet noted she got sick after volunteering at a cleanup along the river, despite immediately taking a shower once she got home.

Persistent pollutants

Dioxins are a group of chemically related compounds that belong to the “dirty dozen” — a group of dangerous chemicals known as persistent organic pollutants. They are highly toxic and carcinogenic and can cause reproductive and developmental problems, damage the immune system, and interfere with hormones.

Dioxins are hydrophobic, which means they don’t dissolve in water, and they are considered a stable chemical, which means they never break down. Since even a trace amount of dioxin can cause harm, they are measured in parts per trillion (ppt).

Historic dioxin levels at the Centredale Manor site have ranged from 94 to 8,200 ppt. For comparison sake, the EPA’s maximum contaminant level for dioxin in drinking water is 0.03 ppt.

“These dioxin levels are among the highest we’ve seen in New England for aquatic sediments,” Richard Pruell, a scientist at the EPA’s Narragansett Laboratory, said in 1998.

The Centredale Manor site was placed on the EPA Superfund list two years later. Remediation work, much of it taxpayer funded, has included capping, the removal of waste and contaminated soil, and the removal of contaminated sediment in Allendale and Lyman Mill ponds.

Attempts to reduce the amount of metals making their way into the river began in the 1950s, but federal requirements for industrial pretreatment of wastewater did not go into effect until the 1972 Clean Water Act.

But concerns about the health of the river and the communities along its banks didn’t begin in earnest until the early 1990s, when the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council was created in part to “improve low-status communities in Providence by transforming the forgotten Woonasquatucket River.”

The Blackstone, Providence, and Seekonk rivers share similar stories.

Air pollution problems

While unregulated and underregulated industry has polluted our waterways, it also has done a number on the air we breathe, especially to the lungs of people living in communities sacrificed for profit and the convenience of others.

The above video, taken on the afternoon of Aug. 28, 2017, shows pollution spewing from the smokestack of a scrap-metal operation on Delaine Street in Olneyville.

The video was shot by a former Olneyville resident from the fourth floor of the Rising Sun Mills apartments on Valley Street. The person who shot the video admitted it “is a particularly bad example” of the pollution the community regularly experiences. But the amount of less-egregious pollution — combined with outbursts of more-noticeable occurrences — foisted upon the neighborhood quickly adds up.

Forty-one percent of residents in the Providence neighborhood were diagnosed with a chronic disease or had a family member diagnosed with a chronic disease, such as asthma, diabetes or heart disease, according to a community assessment conducted a decade ago by DOH.

Obesity and tobacco use certainly factor into the community’s health outcomes, but so does the amount of pollution this neighborhood, walled off by the 6-10 Connector from the rest of the city, is forced to live with.

And invisible pollution is just as concerning as the nasty concoctions that pour out of smokestacks and tailpipes. In fact, Rhode Island is fond of building low-income housing, assisted-living facilities, and schools on top of ground loaded with unknown mixtures of waste.

Shhh: Hidden dangers

On a March morning in 1999, residents in the Providence neighborhood of Hartford — separated from Olneyville by Route 6 and the Woonasquatucket River — saw bulldozers breaking ground on an overgrown but well-known former dump. The Springfield Street site had been selected for two new schools — DelSesto Middle School and Anthony Carnevale Elementary School — a year earlier, but construction began before the work was permitted, with no communication to the surrounding community.

While an estimated 300,000 tons of waste and fill material were dumped in the Springfield Street landfill before the site became overgrown, it was never a licensed facility. But during debate about the construction of the proposed schools, the city, which had operated the site in the 1960s and ’70s, denied that it had been a dump at all.

Dirt testing, however, revealed the site was contaminated with heavy metals and VOCs — toxic compounds that easily escape the ground and enter the air we breathe. While capping can block heavy metals — the Springfield Street site was capped with 2 feet of clean soil — remediating VOCs is more difficult. Buildings can have a “chimney effect,” pulling volatile substances out of the ground and into the interior air.

Children are particularly vulnerable to toxic vapors circulating in a building.

Concerned neighborhood parents and residents teamed up with Rhode Island Legal Services to file civil action lawsuits against the city and DEM. One suit charged environmental racism, because the prospective student body was predominantly children of color; another charged failure to give adequate notice of the planned construction and demanded the schools not be opened due to potential hazards.

The schools were completed, and operate to this day. To mitigate the potential health hazards, both schools have foundation-level ventilation and air-monitoring systems, which are supposed to be inspected quarterly.

Another Providence school, Jorge Alvarez High School in the city’s southern Reservoir Triangle neighborhood, also was built atop spoiled ground.

In the past 20 years, the non-white share of the neighborhood’s population increased from 25.7% in 1990 to 59.5% in 2000 to 71.7% in 2010, according to a 2011 white paper titled The Demographics of the Reservoir Triangle.

Alvarez High School, which opened in 2007, was built on remediated land that had been heavily contaminated by the Gorham Silver Manufacturing Co., which operated there for 94 years before closing in 1986.

The 37-acre site that stained the surrounding neighborhood was contaminated with industrial pollutants, such as the familiar alphabet soup of toxins PCBs, TCE, PCE, and PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), that degraded soil and water quality, most notably that of Mashapaug Pond. (While in operation, Gorham used the 4-acre company-owned cove on 70-acre Mashapaug Pond as a waste lagoon.)

The city’s largest water body shares a similar past and present with the Woonasquatucket River. It is unsafe to eat fish from Mashapaug Pond or come in contact with its water.

When Alvarez High School was built, the surrounding parcels — also part of the polluted Gorham property — were left unremediated. A DEM lawsuit against the city brought a court order for increased fencing and signage between the school grounds and unremediated areas.

In 2010, ecoRI News reported there were broken locks on the gates and gaps in the fence between the school and the neighboring toxic land. Local residents told us they had seen children playing on a pile of contaminated dirt behind the loosely erected fence.

Fourteen feet. That was the distance from the westernmost outer wall of Alvarez High School to the 8-foot-high fence. For five-plus years a few signs and the shoddy fencing — a lawsuit was required to even make that happen — were the extent of the efforts made by the city to clean up hazardous material next to a public school.

Much of the anger the community vented about the site of Alvarez High School, which is also equipped with air monitors and sub-slab ventilation, and the contaminated parcels next door centered on a lack of communication and concern from city officials.

The polluted pile was eventually removed and the neighboring site remediated largely because of the tireless work of Amelia Rose, then director of the Environmental Justice League of Rhode Island; a 38-page health consultation presented to the public at a meeting in August 2010 by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, an Atlanta-based federal public-health agency; and a marginalized community that began to push back.

In 2012, the General Assembly passed a bill that prohibited the construction of schools on industrial waste sites where there is potential for toxic vapors to seep into classrooms. The law was proudly touted by state officials as the most stringent in the nation.

Ten months later, a movement was underway to gut the law and allow construction of schools on contaminated industrial sites where there could be potential vapor intrusion. In fact, DEM, one of the original legislation’s most avid supporters, submitted testimony in favor of two bills looking to revise the law.

The Rhode Island Mayoral Academies pushed for the revision so it could build a new publicly funded charter school on a contaminated site on Roosevelt Avenue in Pawtucket. “If we don’t develop these properties, then they lie fallow,” an attorney for the organization said at a Statehouse hearing in early 2013.

At the same 2013 Statehouse hearing, Rose, who pushed hard for the 2012 law, noted she supported the idea of reusing brownfields, but not at the possible expense of society’s most vulnerable.

“We value the reuse of brownfield sites. It doesn’t do anyone any good to leave them festering,” she said. “But there are appropriate uses, like commercial, industrial uses that aren’t polluting and open space, which many inner-city neighborhoods are lacking. They would be excellent sites for solar panel arrays and wind farms. They’re not appropriate for schools, senior centers, and shelters.”

Rose, who is now the executive director of Groundwork Rhode Island, concluded her testimony by saying the use of contaminated sites for the latter impacts populations society deems expendable and disposable.

A few years later, two well-known supporters of the Rhode Island Mayoral Academies, Central Falls Mayor Charles Moreau and House Speaker Gordon Fox, were convicted on federal corruption charges.

The project never materialized.

Toxic air kills

By the 1970s there was so much air pollution in some U.S. cities that it was often difficult to see the sky. Progress has been made, but some 200,000 people in the United States still die every year from toxic air, many of them people of color or low-income. Air pollution can raise the risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, lung cancer, and stroke. People who have medical conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and hypertension are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution.

Air pollution causes about 4.2 million deaths annually worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. The Switzerland-based organization estimates the escalating climate crisis will cause an additional 250,000 deaths a year between 2030 and 2050.

Last month, a new report — Pollution and Health: A Progress Update published in The Lancet Planetary Health — found pollution is the world’s largest environmental risk factor for disease and premature death, causing one in six deaths worldwide.

“Urgent attention is needed to control pollution and prevent pollution-related disease, with an emphasis on air pollution and lead poisoning, and a stronger focus on hazardous chemical pollution,” according to the May 17 report. “Pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss are closely linked.”

The recent report is an update on a 2017 publication by The Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health that addressed the devastating health impact and economic costs of air, water, and soil pollution on humans and the planet.

Most of this death and destruction is tied to the extraction, transport, and burning of fossil fuels.

By 2050 it is projected that the number of heat waves in Rhode Island will quadruple to about 40 days a year. This is of particular concern given that three of the state’s five counties — Kent, Providence, and Washington — flunked the American Lung Association’s latest air pollution test. (There is no monitor collecting data for the other two counties, Bristol and Newport.)

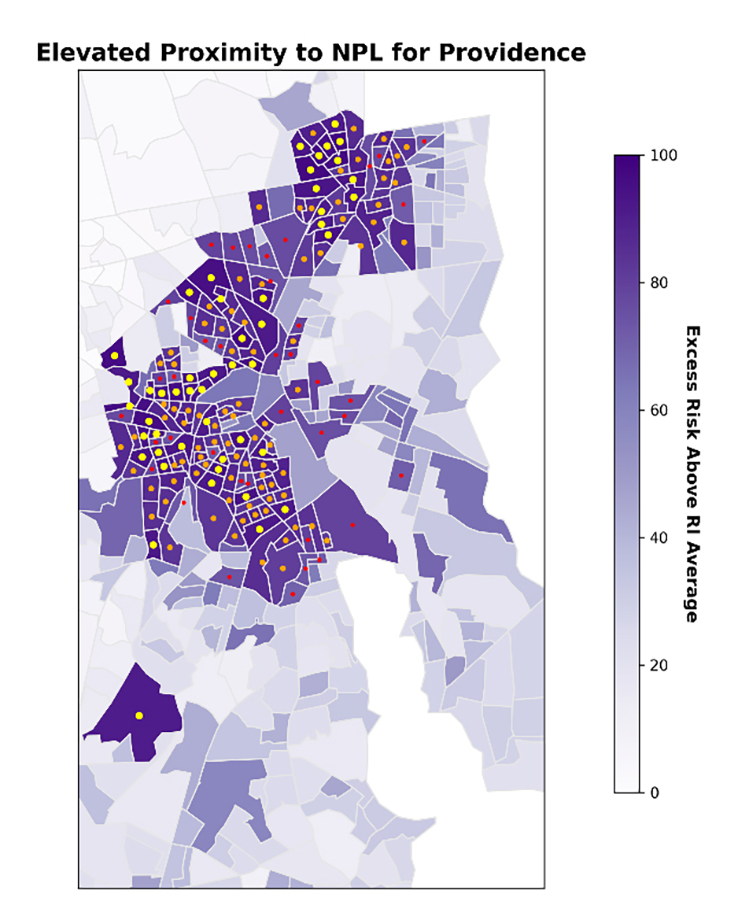

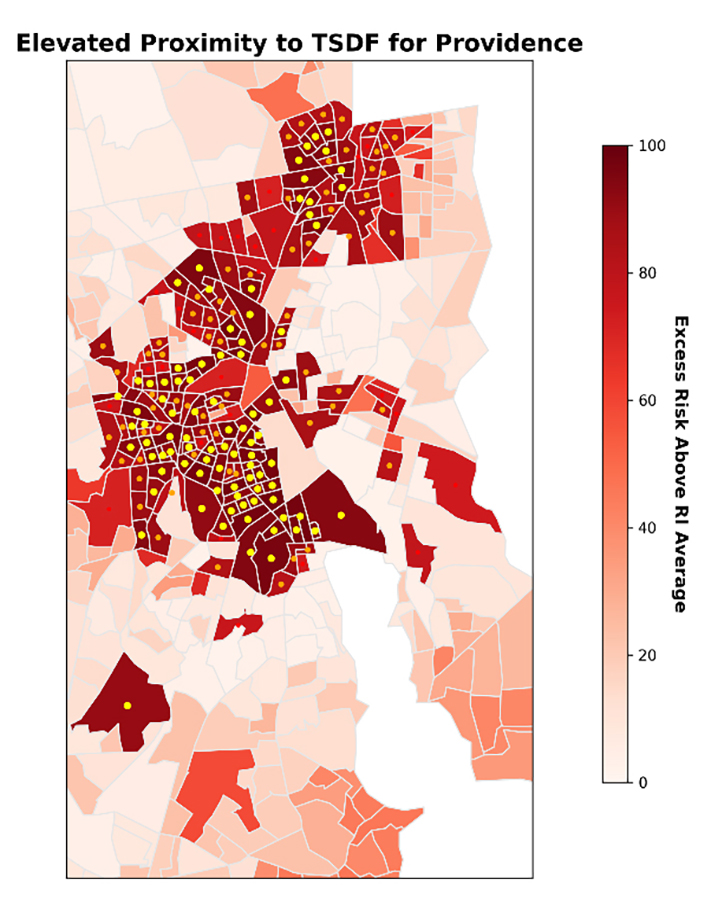

More than 100,000 Rhode Islanders live with asthma, and some 55,000 adults have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, according to DOH. They are disproportionately impacted by an increase in ozone levels and particulate matter, such as the levels experienced in Olneyville, South Providence, Washington Park, and other areas in the state’s urban core.

A 2021 study found people of color in Rhode Island have been exposed to significantly higher levels of air pollution than white people for decades.

Black people nationwide are three times more likely to die from air pollution than white people, in part because they are 70% more likely to live in counties that are in violation of federal air pollution standards. A 2014 study found that, on average, people of color are exposed to 38% higher levels of nitrogen dioxide pollution than white people.

Nitrogen dioxide comes from sources such as vehicle exhaust and power plants. Breathing it is linked to asthma and heart disease. The EPA lists it as one of the seven key air pollutants it monitors.

The transportation sector accounts for 35% of Rhode Island’s greenhouse gas emissions and plenty of air pollution, especially for the people who live or go to school near interstates 95 and 195. But despite last year’s Act on Climate law that mandates the state lower climate emissions by 2030, Rhode Island has no plan in place to reduce tailpipe emissions.

In its 2014 study, University of Minnesota researchers found that in most areas lower-income non-white people are more exposed to air pollution than higher-income white people, and on average, race matters more than income in explaining differences in nitrogen dioxide exposure.

Rhode Island, at No. 6, was ranked in the 15 states with the largest NO2 exposure gaps between white people and people of color, according to the study.

When it came to the 15 urban areas with the largest exposure gaps between white people and people of color, Providence ranked No. 5, right after Boston.

Same as it ever was

Last week the Senate showed how much it cares about pollution and the public health/climate problems it creates by passing a bill that would allow the incineration of plastic — a process greenwashed by the plastics industry as “advanced recycling.”

The 19 senators — and the five others who couldn’t be bothered to show up for the June 7 vote, for fear of perhaps voting against the will of Senate President Dominick Ruggerio, D-North Providence, and the fossil fuel industry — decided business interests outweigh established environmental law that prohibits the burning of plastic waste. The legislation is opposed by every major environmental organization in the state.

As Kevin Budris, a senior attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation noted, if this bill becomes law, “advanced recycling” facilities could move into Rhode Island without the same siting restrictions, operating standards, public permitting processes, and government oversight that apply to other waste and recycling facilities.

The amended version of the bill that passed did place restrictions on where these plastic-melting facilities could be located. The legislation limits these operations to within a mile radius of a state facility. Countryside Drive in North Providence is safe, but neighborhoods around the Central Landfill in Johnston and the Port of Providence are targeted in the bill.

Pyrolysis, which an American Chemistry Council lobbyist told legislators last month is an advanced technology, is a century-old practice that heats solid organic matter in the absence of oxygen, resulting in the release of gases, oils, and char. Creating the heat necessary to melt plastic takes a lot of energy, and more is needed to treat the waste than can actually be recovered. That is why few pyrolysis facilities to manage waste are in operation around the world.

The bill refers to melting plastic as innovative and a solution to the environmental challenges Rhode Island faces, but fails to note this energy-intensive process is inconsistent with Act on Climate mandates.

The bill begins with “Rhode Island is committed to a clean environment and protection of its natural resources,” but fails to note the amount of heavy metals and dioxins that will be concentrated in the resulting byproducts.

Those who sponsored the controversial bill appear more concerned about the life expectancy of the Central Landfill and the wants of special interests than the heath of their constituents.

The names of politicians, department heads, businesses, and processes change, but the unjust system plows on.

To view the series, click here.

I’m not quite sure what Rhode Island would do without the meticulous, human-centered work by ecoRI to expose the state’s environmental problems and the people who, often willingly, exacerbate them. Please keep up the good work.

This article is great and points out a number of environmental issues facing Rhode Islanders, but I would like to point out what I see as a major misrepresentation of facts in the Persistent Pollutants section. The author points out that historic dioxin levels at the r site have ranged from 94 to 8,200 ppt (parts per trillion) and then notes that “the EPA’s maximum contaminant level (MCL) for dioxin in drinking water is 0.00000003”. First off, it is absolutely required that the MCL have a unit on it, otherwise it is insinuated that the unit is ppt, which is untrue. The .00000003 limit has units of mg/L. .00000003 mg/L actually equals .03 ppt. Clearly, the 94 to 8,200 ppt concentrations previously identified are wildly out of compliance, so there is no need to misrepresent the EPA’s MCL. The sentence should read “the EPA’s maximum contaminant level for dioxin in drinking water is 0.03 ppt” if the article is to be scientifically accurate and perceived as trustworthy.

Elena, mistake corrected. I didn’t make the adjustment. Nothing sinister. Just an English major exhibiting his math skills.

Important, well-researched article!

EcoRI is a very important source of information for all Rhode Islanders.