Environmental Injustices Dumped on Two Providence Neighborhoods Illuminate Impacts of Structural Racism

May 23, 2022

PROVIDENCE — Environmental injustices and the apathetic attitudes that allow them to fester collide head-on in two neighborhoods along the city’s toxic waterfront. This intersection of societal inequality highlights the numerous environmental justice issues Rhode Island faces, from heat islands in the state’s urban core to the historic theft of Indigenous lands to an absence of safe and convenient transportation choices to a lack of access to affordable housing and healthy food.

The neighborhoods of South Providence and Washington Park are connected by Allens Avenue — arguably the state’s most distressing roadway.

Residents, businesses, schools, and health clinics in the area are forced to deal with a headache-inducing stink, heavy truck traffic, illegally idling vehicles, and government officials who have long done little to nothing to reduce the unfair burden placed on these communities in the name of economic growth.

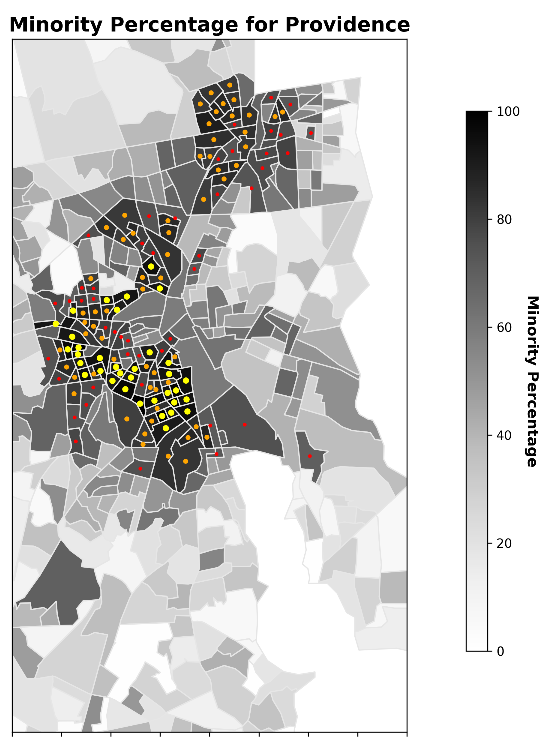

Sen. Tiara Mack, a Providence Democrat who was elected to the Rhode Island Senate in 2020, has said companies in the Port of Providence have long believed they could “pick on” the surrounding communities, which, she has noted, are predominantly Black, brown, and low-income. The 2016 Brown University graduate and many others believe it is time for local and state officials to start listening to the neighborhoods’ concerns.

The city’s industrial waterfront is perfectly placed to pollute the nearby neighborhoods, according to Sarah Hsu, a founding member of Medical Students for a Sustainable Future, who served as the organization’s 2021 executive chair.

“It is unfair right now that across the street at the Providence Community Health Center, nearby at the Chapman Primary Care Clinic, we are seeing patients who are breathing this toxic air, and that is not all right,” Hsu, a Brown University medical student, said last year during a protest of fossil fuel expansion in the Port of Providence. “At best we should start tearing down everything in this port, at minimum we should be doing nothing. But at no point should we be expanding.”

From Davol Square to the north and Washington Park to the south, the area is or has been home to dilapidated buildings tagged with graffiti, mountains of scrap metal, illegally piled asphalt, mounds of coal, liquefied natural gas and propane storage tanks, a shell terminal, chain-link fences topped with barbed wire, vacant and neglected properties trashed with all sorts of debris, and a buffet of stored chemicals, many of them combustible and/or toxic.

Sidewalks often obstructed by overgrown vegetation and bicycle lanes covered with grit and litter welcome pedestrians and bicyclists brave enough to make the journey. When the wind blows from the west, recreational boaters and anglers say dust from the scrap-metal operations that line Allens Avenue creates a sheen of pollution on the Providence River’s surface.

Businesses in the Port of Providence that pollute the environment are afforded more rights than those who suffer the consequences. The receipts go back years.

For instance, it is criminal for anglers, some of whom are fishing to feed their families, to take too many striped bass and tautog from the polluted waters around Providence, but it is only a civil offense to actually pollute said waters.

The anglers’ offenses are deemed illegal, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) emails press releases and posts the arrests on social media, and punishment is swift.

But an Allens Avenue business that opened in 2009 without many of the required permits, including the one needed to conduct car-crushing operations, and is caught dismantling, in the Providence River, vessels it doesn’t have the authority to be storing is issued toothless administrative violations. These notices of violation are buried on DEM’s website and no press releases are issued. The company’s illegal operation and the pollution it generates continues to this day.

A similar story has played out for a petroleum-storage business on Allens Avenue with a history of odor complaints and noncompliance.

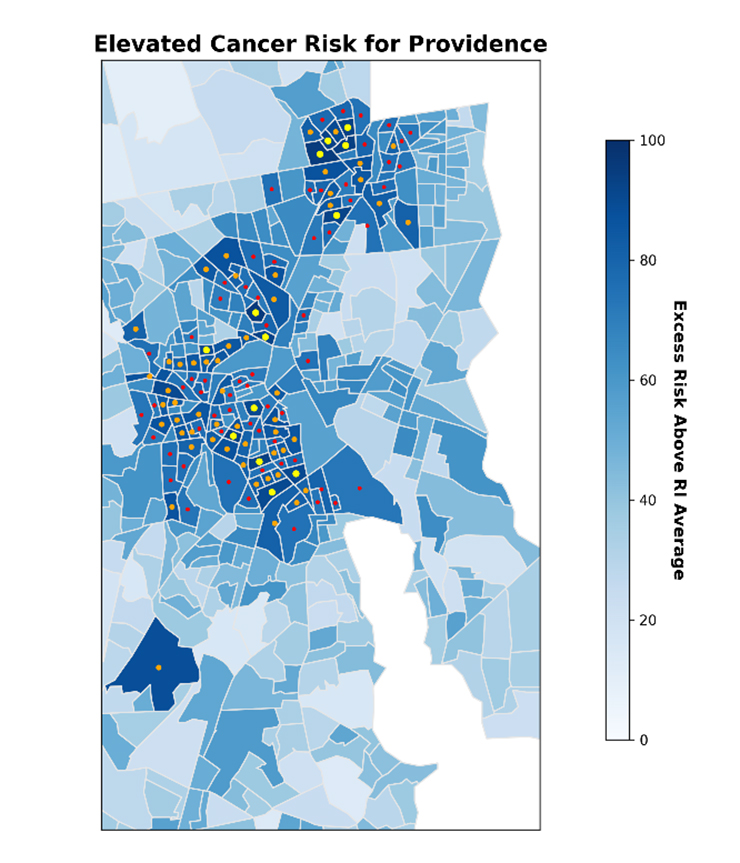

South Providence’s population is 90% people of color: 55.8% Latino and 34.2% Black. Washington Park’s population is nearly 61% people of color: 46.9% Latino and 14% Black.

Unjust living conditions

Front-line communities, like these two Providence neighborhoods and other sacrificed areas in the state, across the country, and around the world, bear the burden of environmental degradation and deteriorating public health. These communities, in which people of color are typically the majority, routinely deal with poor air and water quality, toxic industries operating nearby, a lack of green space, and increasing summer, and spring, heat.

The people who live in these neighborhoods don’t seek these conditions. They are forced upon them for different reasons, none of them just. The inequities expand around them, despite their fears, because those in power have deemed these neighborhoods can be defiled in the name of economic growth. Low wages — the federal minimum wage has been stuck at $7.25 since 2009 — and a lack of affordable housing outside of these sacrifice zones leave few options for single parents, those living on fixed incomes, and families struggling financially.

South Providence resident Monica Huertas, founding director of The People’s Port Authority, a community organization created to oppose the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure along the Providence waterfront, has noted the exhausting effort required in “constantly needing to build massive grassroots resistance whenever a corporation wants to put a polluting facility in our neighborhood.”

About a dozen polluters are routinely listed in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxics Release Inventory for the city’s 02905 zip code. This section of Providence contains a greater number of polluting facilities than any other zip code in Providence County.

Air pollution from the Port of Providence and Interstate 95 has caused the South Providence and Washington Park neighborhoods to endure some of the highest rates of asthma in southern New England — a problem that will get worse as temperatures rise and ozone alert days increase, according to the city’s own Climate Justice Plan.

Rhode Island as a whole has the fourth-highest rate of asthma in the country, with 11.2% of the population suffering from the respiratory condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The national average is 7.8%.

Community pushback

During the past half-dozen years, especially when a liquefied natural gas (LNG) expansion project proposed by National Grid was pushed through — thanks largely to acquiescent elected officials, a governor who forbade the Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH) from commenting on the controversial facility, and state agencies more concerned about business interests than the public’s well-being — South Providence and Washington Park residents began to push back.

“We quickly realized … that it wasn’t just about LNG or liquefied natural gas, but it was about LPG, liquefied petroleum gas, and scrap metal and tar and cement — all these pollutions and companies all in one spot,” Huertas said during a March 29 environmental justice forum sponsored by the Rhode Island Sierra Club. “Tanks and chemicals, and just all these crazy things on top of each other. Things that you will never find in a high-income neighborhood or in a white neighborhood, especially if that neighborhood is high-income.”

In response, residents of South Providence and Washington Park raised their concerns, and voices, at public hearings. They created community groups, such as The People’s Port Authority. They protested outside the Statehouse. They organized toxic tours of their neighborhoods. They took time away from their families and sacrificed free time in hopes of keeping their communities from becoming more toxic.

This more-aggressive approach eventually got community members seats on stakeholder groups, giving them more of a say in the future of their neighborhoods. But the communities’ invisible past, when few spoke in their defense, continues to put residents at risk.

Jennifer Rourke of Renew Rhode Island, a member of the Renew New England Alliance that has 150 members working to make sure people have, among other things, clean water and clean air, noted during the March forum the need for the state to address racial discrimination by listening to the people who live, work, and play in South Providence and Washington Park.

“Everyone knows that smell, and it bothers everyone,” the Warwick resident said. “So just imagine if you have to live there every day, so why not do the right thing and clean up the community.”

For decades the public-health impacts of building more polluting infrastructure along the Providence River and upper Narragansett Bay were barely debated, much less mentioned or considered.

Operations along the Allens Avenue waterfront include a hot-mix asphalt plant that emits compounds linked to child development disorders and to cancer, and an oil terminal that emits similar pollutants and other toxins linked to neurological and respiratory disorders.

The area is also home to chemical-processing plants. At one facility operated by a packager and distributor of specialty chemicals, some 3 million pounds of chemicals, such as chlorine, ammonium, and formaldehyde, are stored.

“The Port of Providence has a long history of environmental problems that concentrate many of Rhode Island’s most concerning pollution and safety issues in neighborhoods that are economically and racially disadvantaged. Because of that history, the residents of the area feel disenfranchised and believe that their voices and health do not matter to government,” according to a three-page DOH letter critical of the National Grid LNG project. “Although the current project does not appear to make those pollution and safety problems substantially worse, it continues that historical pattern of discounting the voices of the people that live in the region and sets a precedent that may lead to additional, more concerning, projects in the future.”

Then-Gov. Gina Raimondo ditched the letter before it was to be submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

A late-November 2017 hearing in the basement of the Rhode Island Department of Administration building on Smith Street, which featured a notable police presence, provided a delayed opportunity for opponents to express concerns about National Grid’s LNG expansion proposal.

Rep. Marcia Ranglin-Vassell, D-Providence, called the project a “toxic facility” and an “environmental threat.” “Our community is not a dumping ground for rich corporations,” she said.

The project, despite significant community opposition, was approved less than a year later.

Continued push of pollution

Last spring, after another fossil fuel expansion project had been proposed for the Providence waterfront, a crowd of about 100 people, rallied by The People’s Port Authority and the Rhode Island Interfaith Coalition to Reduce Poverty, gathered in opposition at the corner of Allens Avenue and Terminal Road.

David Veliz, director of the Interfaith Coalition to Reduce Poverty, noted the amount of pollution South Providence and Washington Park residents are subjected to is a clear example of environmental injustice that has gone unchecked by those in power.

“You can’t get more inequality than the environmental racism we’re seeing in this community,” he said.

A Texas-based propane storage and wholesale company is looking to add six 90,000-gallon LPG storage tanks to its Port of Providence footprint. The tanks would link up Sea 3 Providence LLC, a subsidiary of Blackline Midstream LLC, to an existing rail line for liquid petroleum gas delivery by train and expand its Fields Point operation, which currently hosts a 19-million-gallon cold-storage tank.

“We’re saying enough is enough, and we certainly can’t add six more tanks,” Huertas said at the June 10 protest.

Terri Wright, a resident of the area and an organizer with Providence-based Direct Action for Rights and Equality, said neighborhood pollution is multi-leveled. With each breath, she said, residents are forced to “pick your poison.”

“What community can reach its full potential under these conditions?” Wright asked.

Alfred Jeffries shares the communities’ concerns.

While he doesn’t live in South Providence or Washington Park, his South Elmwood neighborhood is close by. For years he has witnessed the decline in environmental and public health in the neighborhoods to his north and supports efforts to right the wrongs.

He is also now concerned that deterioration could reach further into his neighborhood — which was drastically altered in 1966 when Route 10 opened, taking with it a chunk of Roger Williams Park — with LPG being delivered on railroad tracks that are a difficult putt from some residents’ back yards in a densely populated neighborhood.

The 79-year-old’s home doesn’t abut the tracks that carry freight to and from the Port of Providence, MBTA commuters, and Amtrak and Acela passengers, but he is concerned the damage a flammable fuel “rumbling through the neighborhood and past people’s homes” could have should there be an accident.

“This is not a wealthy neighborhood and dragging LPG through it is too much, in my opinion,” said Jeffries, a member of the South Elmwood Neighborhood Association who has lived at his Potter Drive home for nearly 40 years. “It crosses a line and endangers people and property.”

Don Rotteck has lived on Alger Avenue for three and a half decades. Trains go zipping past the six railroad tracks behind his home throughout the day, but it is the constant moving of freight cars at night and at 2 and 3 in the morning on weekends that disturb his quality of life.

They both believe efforts should be focused on making stressed communities safer, healthier, and greener.

“Every neighborhood deserves a park where kids and adults can play and have a nice time,” said Jeffries, who lives within walking distance of Roger Williams Park and Joseph Williams Field.

The future of the Sea 3 project resides with the state’s Energy Facility Siting Board (EFSB).

Support grows slowly

Times are changing, albeit slowly, for the Washington Park and South Providence neighborhoods.

The Sea 3 project, like the waste-processing and transfer facility proposed before it, has drawn intense opposition from neighbors, businesses, and environmental groups. Both proposals, however, also drew the rebuke of elected officials and government offices.

The developer of the dump proposed for the corner of Allens and Thurbers avenues pulled the project after the mayor announced his opposition and the city’s planning and development deputy director recommended the City Plan Commission reject it.

The City Council unanimously passed a resolution in December calling on the EFSB to commit to a full review of Sea 3’s proposal. (The board did just that at an April 21 hearing.) The Providence Emergency Management Agency director has noted her concerns with Sea 3’s plan to expand its LPG operation.

The mayor, attorney general, dozens of state legislators, and DEM have also come out against Sea 3 expansion.

“Residents of South Providence have historically been ignored and underrepresented in the decision-making process surrounding the most intensive industrial land uses in the State,” City Council President Pro Tempore Pedro Espinal wrote in a statement following the council’s Dec. 2 vote. “We as a community have come together as one voice to clearly state that we do not support any expansion or development in the Port of Providence that may lead to increased safety risks for the local residents. I look forward to moving forward with legislation and public advocacy that will uplift our community and conserve our environment.”

Susan Shim Gorelick is a Jamestown resident but she has witnessed firsthand how Washington Park, South Providence, and other distressed communities in Rhode Island have suffered.

It is why she founded the Coalition Center for Environmental Sustainability, to help build a movement that connects with the people who are living with these burdens and to champion environmental, social, and economic justice for all.

Gorelick, who came to the United States from South Korea 45 years ago when she was 15, told ecoRI News that to address these inequalities the people living in silenced and marginalized communities need to be heard.

She said imposing organizational or funder agency on these communities — or on the environment, for that matter — won’t solve the problems that engulf them.

“We are all in this together,” Gorelick said. But “Rhode Island is so small those people in power … if you are not in their group and if you don’t have groupthink … they will keep you at arm’s length. At the same time, guess what, who suffers: community that really needs.”

To view the series, click here.

This is an inconceivable and absolutely intolerable situation; I’m surprised the port is allowed to operate at all. It’s a city neighbor for God’s sakes! With the elections coming up, what are the candidates’ stands? It’s obvious the port should be shut down; it’s a situation on the verge of a horrendous accident. Will there be anything on the ballot about this? The population is so vulnerable; I had no idea RI had such a high asthma rate. –

This is a disgusting and Toxic article illustrating peoples lack of sense and use Race as a divisive device. The Working Waterfront is a necessary means in our industrialized city and the communities have been built around the working waterfront , not the other way around . I’m sorry but long ago this part of Providence was home to the Largest Costume Jewelry Manufactures in the world producing untold amounts of pollution . All theses politicians do cause problems and offer no viable solutions . Where they suppose the Fuels we depend on be stored . The Gasoline the makes it possible for us to drive to work , the Diesel Fuel we depend on to heat our homes and deliver our commercial goods . Stop victimizing lower income individuals and Turning our businesses into Villains .