Climate Crisis Slams Headfirst Into Public Health

Continued burning of fossil fuels is choking Rhode Island’s wellness

December 12, 2022

The Ocean State is on the front lines of the climate crisis, the tentacles of which reach into almost every social determinant of health — clean air, safe drinking water, sufficient food, and secure shelter.

But the many effects climate change is having and will have on public health, from the serious to the modest, are often lost among conversations about sea-level rise, melting glaciers, drought, and extreme weather.

A policy brief published in October in The Lancet highlighted the impacts climate change is having on public health, noting the burning of fossil fuels has “created an accelerating health crisis. The health impacts in the U.S. are far-reaching and predicted to increase in the coming years.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that between 2030 and 2050, the climate crisis is expected to cause about 250,000 additional deaths worldwide annually, and not all of those lives will be lost in hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, and flooding. Many of those lives will be lost to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress.

The direct damage costs to health are estimated to be between $2 billion and $4 billion annually by 2030, according to the Switzerland-based organization.

“The phase out of polluting energy systems, for example, or the promotion of public transportation and active movement, could both lower carbon emissions and cut the burden of household and ambient air pollution, which cause 7 million premature deaths per year,” according to WHO.

While climate change most certainly poses a significant threat to future human health, an increasing number of people here and across the globe are already feeling the effects of health woes brought on by this worldwide emergency.

The Lancet policy brief noted that in July nighttime temperatures were the warmest in U.S. history, and nearly two-thirds of people across the continental United States and Puerto Rico were affected by drought.

“Communities and health systems across the U.S. face compounding health crises including the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, gun violence, racial injustice, and economic insecurity,” according to the policy brief. “Climate change and its health risks converge with these crises, furthering the urgent need for decisive action to protect health.”

Global warming, human health, and equity are explicitly bound, and the impacts can be devastating, from the obvious (displaced families after big storms) to the hidden (wildfire smoke accounts for a quarter of fine particulate matter in the United States).

In 2021, more than 200 leading health and medical journals around the world called climate change the “greatest threat to global public health.” A 2021 paper noted human health “is already being harmed by global temperature increases and the destruction of the natural world.”

“The science is unequivocal; a global increase of 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average and the continued loss of biodiversity risk catastrophic harm to health that will be impossible to reverse,” according to the paper published in The Lancet.

In September, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a report calling the climate crisis “the most significant public health challenge of the 21st century.”

Health issues

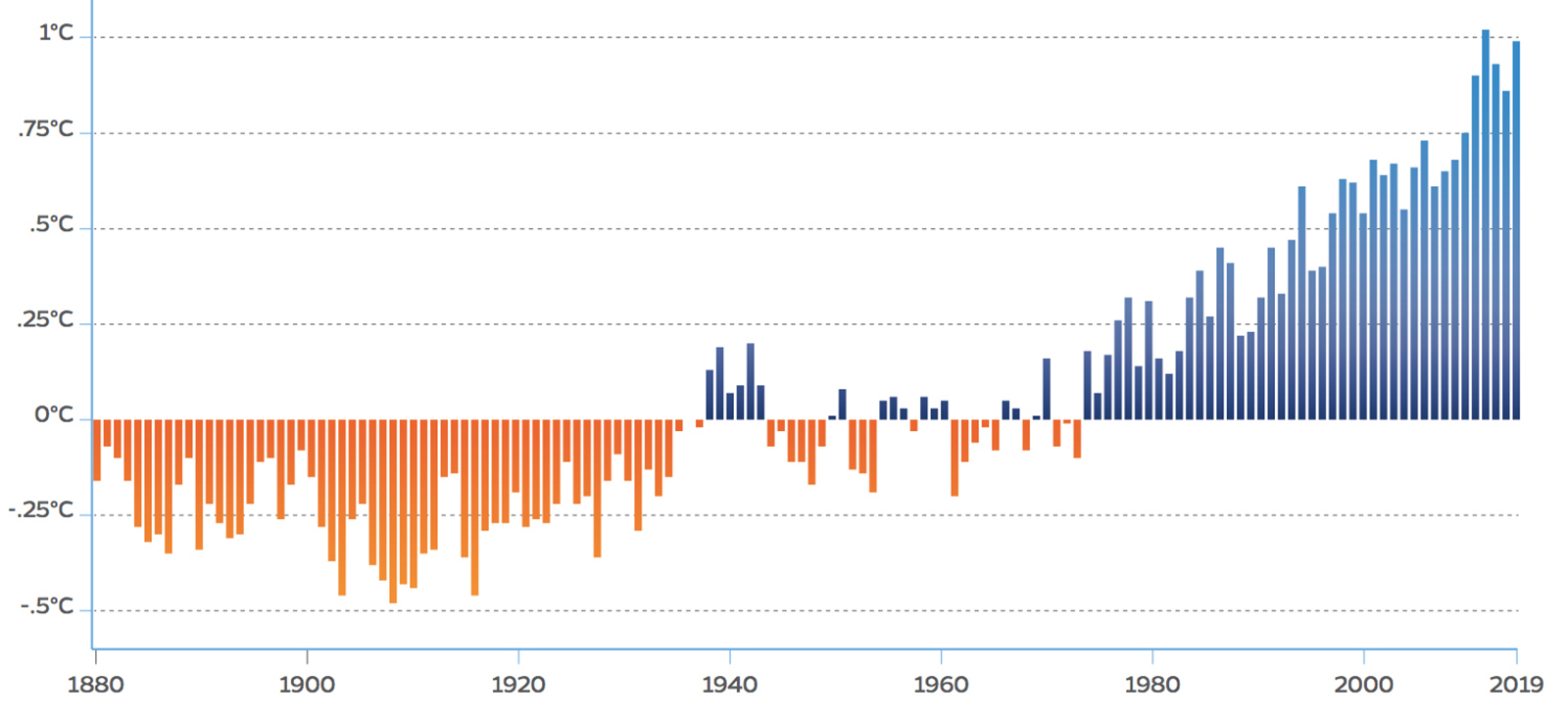

Since the turn of the 20th century, the average annual temperature across the contiguous United States has risen 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, and the country is projected to see the temperature increase up to another 2.5 degrees by the end of this century, because of past climate emissions alone. (Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases can stay in the atmosphere for centuries, and the oceans are slowly absorbing the heat trapped by these gases.)

Over the past 150 years, atmospheric carbon dioxide has risen from 280 parts per million to 420; more than a quarter of that increase has occurred since 2005, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Some climate-related events, such as hurricanes and wildfires, have immediate and obvious health impacts. Other threats being exacerbated by the climate crisis have a more insidious affect on human health: more frequent heat waves (heat stroke); poor air quality (asthma); increases in water, food, and vector-related disease (Lyme disease); and more intense rains and chronic flooding (allergies).

Rachel Calabro, the Rhode Island Department of Health’s (DOH) climate change program manager, said structural problems “rooted in systemic racism and economic inequities” deepen the health problems being caused by the climate crisis.

“We know that health outcomes are associated with economic and racial disparities,” she said. “Climate change is really going to exacerbate that in myriad ways for, you know, people who are already vulnerable.”

Emily Hough, a senior fellow at Brown University working on health care and climate change, said trees, especially in urban areas, help keep summer temperatures down and help reduce air pollution. But she noted they are lacking in many marginalized neighborhoods.

“That’s another area where you see huge inequity,” she said. “You look at the populations who, for example, live right next to the highway and compare that with the people who live on leafy green streets.”

Heat stroke: Average U.S. summer temperatures from 2017-2021 were 1.4 degrees higher than the 1986-2005 average. The years 2013 to 2021 all rank among the 10 warmest years on record, and 2021 was the 45th consecutive year with global temperatures above the 20th-century average. This year saw record-breaking heat waves across the United States.

When people are exposed to extreme heat, they can suffer from potentially deadly illnesses, such as heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Hot temperatures can also contribute to deaths from heart attacks, strokes, and other forms of cardiovascular disease. Heat is the leading weather-related killer in the United States, according the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Unusually hot summers have become more common across the contiguous 48 states, heat waves have become more frequent and intense, and these trends are expected to continue. As a result, the risk of heat-related deaths and illness is expected to increase.

When Rhode Island sees multiple days of temperatures above 80 degrees, emergency room visits begin to increase, according to DOH. Calabro noted temperatures are now flirting with 90 degrees in early June and early September when students are still in school or returning for a new year.

But harmful summer heat isn’t the only concern; higher winter temperatures are driving some of the country’s fastest warming, particularly in the Northeast. Rhode Island has already surpassed the 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warming threshold, and Connecticut and Massachusetts are approaching that mark.

The effects of heat are not felt evenly across communities. Historically redlined neighborhoods have more oil and gas wells, higher levels of air pollution, less tree cover and green space, and hotter temperatures — up to 12.6 degrees hotter than other neighborhoods.

As a result, residents of these communities experience higher rates of adverse health outcomes such as heat-related illness, cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and poor maternal health outcomes.

“The increasing intensity, duration, and frequency of heat waves due to human-caused climate change puts historically underserved populations in a heightened state of precarity, as studies observe that vulnerable communities — especially those within urban areas in the United States — are disproportionately exposed to extreme heat,” according to a 2020 study titled “The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: A Study of 108 US Urban Areas.”

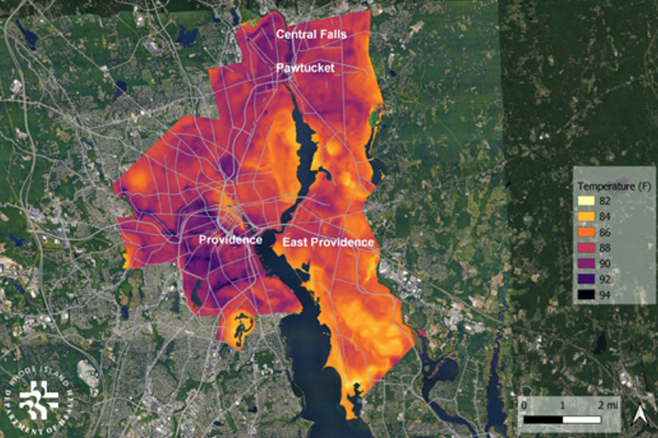

In Rhode Island, research has shown that many neighborhoods in Central Falls, East Providence, Pawtucket, and Providence warm by 10 degrees more than others, according to a 2021 paper co-written by Calabro. She recently told ecoRI News some of these neighborhoods can be as much as 18 degrees hotter at times.

The paper, titled “The Rhode Island Climate Change and Health Program: Building Knowledge and Community Resilience,” noted that from 1981 to 2010 there was an average of 9.3 days of 90 degrees or higher in Greater Providence annually. That number increased to 11 days a year from 2010 to 2014. There were 23 such days in 2020 and 19 in 2021.

Last August, with an average temperature of 77 degrees, tied (August 2018) for the hottest August on record for Providence, according to the National Weather Service.

“Overnight temperatures are staying warm. That’s dangerous for our health, because our bodies can’t cool off,” said Calabro, noting high nighttime temperatures deprive people without air-conditioning of time to recover from the day’s heat stress. “If you have multiple days where the nighttimes are over 70 degrees, that’s where we see hospitalizations go up with older people.”

Asthma: Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter, especially from fossil-fuel-burning road traffic, causes childhood asthma, according to the American Thoracic Society.

Thousands of children younger than 5 die prematurely annually from lower respiratory infections caused by air pollution from the burning of oil, gas, and coal, according to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The higher temperatures that come with climate change promote more ground-level ozone, a powerful lung irritant that can trigger asthma attacks. Climate change can also worsen air quality by increasing air stagnation, slowing air pollutant removal in regions experiencing drought, and lengthening the time between rains that remove pollutants from the air.

Despite decades of progress on cleaning up sources of air pollution, more than 40% of Americans — some 137 million people — are living in places with failing grades for unhealthy levels of fine particulate matter or ozone, according to the American Lung Association’s 2022 State of the Air report.

The 155-page report noted Americans experienced more days of “very unhealthy” and “hazardous” air quality than ever before in the two-decade history of the annual report, first published in 2000. Three out of every eight Americans live in counties with F grades for ozone smog. In addition, 27.8 million children and 18.5 million people age 65 or older are exposed to ozone air pollution and face an increased risk of harm. Gasoline- and diesel-burning vehicles are a leading cause of air pollution that causes health problems for vulnerable groups and in marginalized communities.

In Rhode Island, about 100,000 people live with asthma — the state’s low-income adults are 40% more likely than other adults to have asthma, according to DOH — and some 55,000 adults have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and are disproportionately impacted by high levels of ozone and fine particulate matter.

Two of the three reporting counties in Rhode Island, Kent and Washington, improved their grades from F to D, while Providence County maintained a failing grade, according to the 2022 State of the Air report for the Ocean State. These three counties account for 87% of the state’s population. The state’s two other counties, Bristol and Newport, don’t collect the data.

Calabro said DOH has been working with public housing authorities to obtain air conditioners for families who have children with asthma.

“We’re actually physically delivering air conditioners to people and that’s not a sustainable solution,” she said. “We need to work with the Office of Energy Resources and other agencies to really think holistically about who is qualifying for energy retrofits in their homes. How we can get lower-income people and people in public housing and renters to have better access to weatherization and energy efficiency.”

Lyme disease: Studies provide evidence that as temperatures increase and frost-free seasons grow, ticks that carry Lyme disease and other human pathogens will likely continue to expand their geographic and seasonal distribution in the United States, increasing the potential risk of human disease, according to the EPA.

For example, the life cycle and prevalence of deer ticks are strongly influenced by temperature. Deer ticks are mostly active when temperatures are above 45 degrees.

The incidence of Lyme disease in the United States nearly doubled from 1991 to 2018, from 3.7 reported cases per 100,000 people to 7.2, according to the EPA. Maine and Vermont have experienced the largest increases in reported cases, which helps explain why Lyme disease, since 2001, has increased by more than 300% in the Northeast.

The number of Lyme disease cases, the major vector-borne disease in Rhode Island, has risen — the state has the fourth-highest rate of Lyme disease in the country, according to DOH — along with cases of babesiosis and anaplasmosis, according to a 2021 study. The study noted these increases might relate, in part, to climate change, but also listed other environmental changes, such as land use as it relates to habitat and vertebrate host populations for tick reproduction, as possible contributing factors.

Warmer and wetter conditions may also increase the abundance and range of mosquitoes that carry West Nile virus, Zika virus, and other pathogens.

Changes in temperature and precipitation can also affect the growth, survival, spread, and toxicity of waterborne bacteria, viruses, and toxic algae that directly or indirectly cause illness in humans.

In addition to disruptions in food supply caused by drought, flooding, and other extreme weather, warming temperatures and other climate changes are altering the prevalence and distribution of pests, pathogens, and food species, both on land and at sea, with health consequences. For example, warming waters off the coast of Alaska are making shellfish toxic, endangering the lives of Indigenous people.

Scientists also expect climate change to alter the nutritional profile of some foods, as higher concentrations of carbon dioxide can increase carbohydrate production, while also lowering levels of protein and other essential minerals in crops such as potatoes, rice, and wheat.

Allergies: Changing climate conditions can impact the amount of fungal allergens in the air. A 2020 paper titled “The effects of climate change on respiratory allergy and asthma induced by pollen and mold allergens” noted respiratory health can be particularly affected by climate change and that the duration and intensity of pollen/allergy season can be altered by global warming.

Mold proliferation is increased by floods and heavy rains are responsible for severe asthma, according to the paper’s authors.

DOH’s Calabro noted that “if you live in a poorly drained area, flooding is going to impact your home more readily.” The Providence resident said the quality of housing, especially those being rented by low-income families, is a concern, as poor upkeep can lead to mold becoming a health problem. (Other problems caused by derelict landlords include lead paint, drafty windows, and inefficient heating systems.)

Hay fever symptoms are familiar: runny and stuffy nose; sneezing; eye irritation; and itchy nose and throat. The offending allergen for about 75% of people suffering from hay fever is ragweed. Ragweed growth rates increase and the plants produce more pollen when carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases. If fossil fuel emissions continue unabated, pollen production is projected to increase 60%-100% by 2085.

“Thunderstorms during pollen seasons can cause exacerbation of respiratory allergy and asthma in patients with hay fever,” according to the 2020 paper. “A similar phenomenon is observed for molds. Measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions can have positive health benefits.”

Water woes, itchy and scratchy, mental health

When it comes to drinking water, climate pressures are particularly taxing. More frequent and heavy rains and the flooding they cause increase drinking water contamination. The creep of seawater — thanks to sea-level rise and storm surge that is reaching further inland — into private wells and freshwater aquifers is a growing problem in Rhode Island. Drought and increased development is forcing the pumping of more groundwater, which impacts aquifers and private wells.

“Rising air and water temperatures and changes in precipitation are intensifying droughts, increasing heavy downpours, reducing snowpack, and causing declines in surface water quality, with varying impacts across regions,” according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment. “Future warming will add to the stress on water supplies and adversely impact the availability of water in parts of the United States.”

The burning of fossil fuels and the growing accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere also exacerbates common health nuisances. For example, poison ivy grows faster and is more toxic when atmospheric carbon dioxide increases. More than 350,000 cases of contact dermatitis from exposure to poison ivy are reported — many others are not — in the United States annually.

Researchers say the number of cases is likely to increase if poison ivy grows faster and becomes more abundant. The reactions may also become more severe because poison ivy produces a more potent form of urushiol, the allergenic substance, when carbon dioxide levels are higher.

Besides taking a physical toll on human bodies, these effects can also impact mental health and well-being — and some populations and communities are especially vulnerable. High-risk residents include those who are very young or very old, people with a disability, and those living in poverty.

Climate change impacts, including disasters, heat, and economic losses, are associated with increased risk of depression, stress, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, grief, substance abuse, disempowerment, and hopelessness, according to a 2016 scientific assessment.

People who rely on electric medical equipment, for example, spend time during the more frequent and intense storms being fueled by climate change fretting about the electricity going out, especially if they are housebound. Others with severe health conditions worry about flooding making roads impassable.

Susceptibility to the mental health impacts of the climate crisis is higher for communities with close ties to the land, including people living in rural and agricultural areas and Indigenous communities, and for children and young people, according to a 2021 study.

Brown University’s Hough noted climate anxiety is a growing mental-health concern.

More than two-thirds of Americans experience some climate anxiety, according to a 2020 survey by the American Psychological Association. A 2021 global survey found 84% of children and young adults ages 16-25 are at least moderately worried about climate change and 59% are very or extremely worried.

The latter group should be concerned, as children and young adults will disproportionately suffer the consequences of global warming. A 2021 UNICEF report estimated that a billion children will be at “extremely high risk” as the impacts of climate change accelerate.

Health preparedness

A 2020 report by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Trust for America’s Health noted Earth’s climate is changing at a rate unprecedented over the past thousand years.

Although natural variability contributes to these changes, scientists overwhelmingly agree that human activities have been the dominant cause of climate change since the mid-20th century. Emissions of greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels and other human actions are trapping heat in the atmosphere.

The world’s five warmest years have all occurred since 2015, with nine of the 10 warmest years occurring since 2005, according to NASA. This continues a trend that dates back to the 1960s: each decade has been warmer than the previous one.

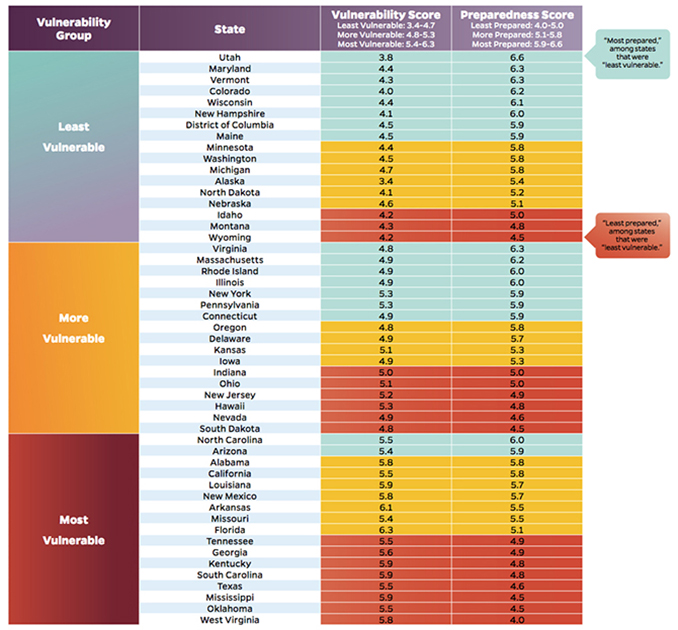

The 140-page Johns Hopkins report assessed all 50 states and the District of Columbia on their level of preparedness for the health effects of climate change. The researchers found a great deal of variation. Some states have made significant preparations, while others have barely begun. Eight states in particular — Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia — are both most vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change and least prepared.

When it comes to climate health preparedness, southern New England’s three states fell roughly in the middle of the pack — Massachusetts (19th), Rhode Island (20th) and Connecticut (24th).

The report’s researchers emphasized that every state, including those rated as most prepared, can do much more to protect residents from the harmful health impacts of climate change.

“The impacts of climate change on our health demand that policymakers respond,” said Megan Latshaw, a scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, when the report was announced. “Our goal is that every single state will take this as a clarion call and think of this report as a starting point to do more to help make residents’ lives safer.”

The Rhode Island Climate Change and Health Program, run by DOH and initially funded by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant, primarily addresses extreme heat, air quality, respiratory illnesses, and vector-borne diseases. Vulnerable populations such as seniors, youth, outdoor workers, and residents in the state’s urban core are the focus of the program’s work.

The program’s main adaptation activities include extreme heat messaging to outdoor workers, Lyme disease outreach to local communities, and climate resiliency in the urban core municipalities.

“It’s not always obvious what kind of health impact you are going to see,” Hough said.

This story was funded by a grant by the EJMP Fund for Philanthropy to examine the intersection of the environment and public health. The other stories funded by this grant can be found here and here.

Thank you for connecting the dots between city planning and public health.

Another factor to consider is that global deforestation is leading to major pandemics as most of the viruses that cause diseases like Covid are coming into humans due to people moving into places that were once relatively uninhabited forests. So deforestation increases the global temperatures and brings new diseases. In order to have a livable planet and livable communities we need to eliminate emissions and protect forests

Thank You for such a well written and informative article.