Ticking Bomb: Climate Crisis Increases Rhode Island Lyme Disease Cases

January 8, 2020

New, emerging research suggests that the climate crisis is bad for human health.

To date, much of the reporting on the climate crisis has focused on the physical impacts of temperature increases, such as sea-level rise, melting ice caps, heat waves, and hurricanes.

Lately, scientists in a diverse range of disciplines have begun studying the wider impacts. For example, the respected medical journal Lancet has reported the results of an international, multidisciplinary collaboration that found widespread adverse health impacts from the climate crisis, such as a downward trend in crop yields worldwide, which threaten food production and food security, and rising temperatures and increased rainfall are increasing vulnerability to mosquito- and tick-borne diseases.

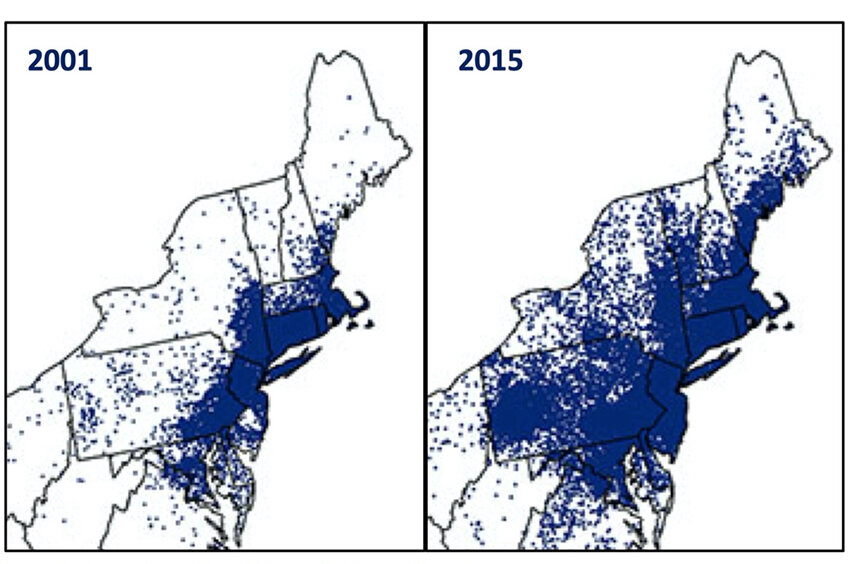

There are important consequences for Rhode Island, where the climate crisis is exacerbating a surge in Lyme disease. In fact, since 2001, Lyme disease has increased by more than 300 percent in the Northeast.

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States. It’s transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Ixodes scapularis — commonly known as the deer tick or blacklegged tick. Typical symptoms include a characteristic skin rash, fever, headache, and fatigue. If left untreated, infection can spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system.

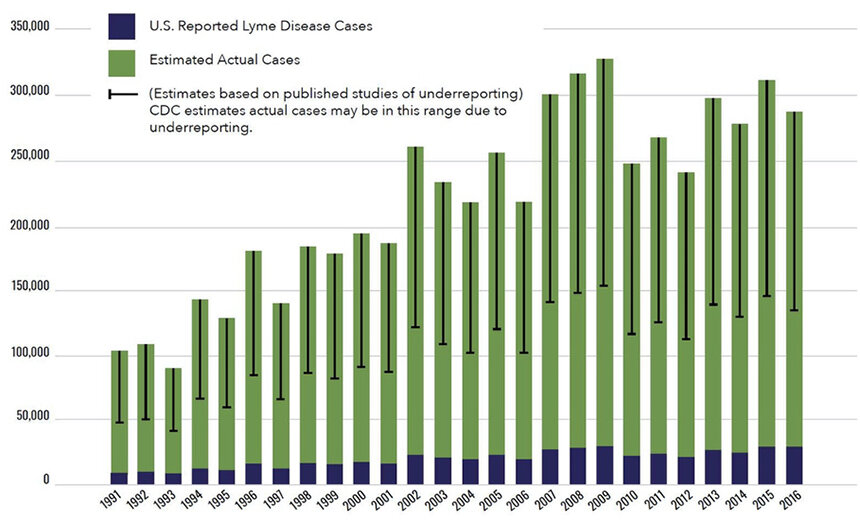

Possible cases of Lyme disease are reported to state and local health departments, which report confirmed and probable cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Each year, about 30,000 cases of Lyme disease are reported.

However, there appears to be a massive underreporting of Lyme disease. Recent research suggests that as many as 300,000 people may get Lyme disease annually in the United States.

Lyme disease appears to be a characteristic example of the link between the climate crisis and the occurrence and spread of disease.

Tick survival depends on environmental factors, and increases in both temperatures and humidity have contributed to surges in the tick population. Edson Severnini, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, projects that the number of Lyme disease cases will increase by more than 20 percent in the coming decades.

Higher temperatures spur ticks to venture farther in search of hosts, such as deer and, since deer are more plentiful after warmer winters, the tick population will increase. Also, as temperatures rise, people may engage in more outdoor activities, increasing their exposure to ticks.

Since ticks spend most of their lives in environments where temperature and humidity directly impact their survival, the Environmental Protection Agency uses Lyme disease as an indicator of climate change.

Most Lyme disease patients who are diagnosed and treated early can fully recover. But, an estimated 10 percent to 20 percent suffer from chronically persistent and disabling symptoms. The number of such chronic cases may approach 30,000 to 60,000 annually, according to a 2018 white paper.

Research by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health suggests that chronic Lyme disease is more widespread and more serious than previously understood and costs the U.S. health-care system between $712 million and $1.3 billion a year.

While a blood test can confirm early Lyme disease, there is no definitive test for the long-term, chronic symptoms, which makes it a “controversial topic in medicine,” according to Emily Adrion, a Ph.D. candidate at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“They cost the health care system about $1 billion a year and it is clear that we need effective, cost-effective and compassionate management of these patients even if we don’t know what to call the disease,” she wrote in the 2015 study.

The CDC estimates the total costs of early Lyme disease to be roughly $1.1 billion annually. When the costs of chronic Lyme disease are added, the total cost jumps to between $26 billion and $77 billion dollars a year.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident.