Get the Lead Out: A Lethargic Work in Progress

Critics say Rhode Island’s efforts are taking too long and placing an unfair burden on low-wealth families and marginalized communities

July 25, 2022

Childhood lead poisoning has declined sharply since its zenith in the 1970s, but it is still a significant problem, especially in Rhode Island’s urban core.

Despite substantial improvements in the prevention of childhood lead poisoning and the passage of lead abatement laws, several hundred children in Rhode Island are still poisoned annually. Many of them live in marginalized neighborhoods.

In 2020, the statewide number of first-time lead poisoning cases among children 6 and younger increased to 472, up from 388 in 2019, according to the Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH).

Of those 472 cases, 69% were recorded in four cities — Central Falls (Pawtucket Water Supply Board), Pawtucket (Pawtucket Water Supply Board), Providence (Providence Water), and Woonsocket (Woonsocket Water Division) — and where 74% of the youth exposed were children of color, according to DOH.

During a late-March environmental justice forum sponsored by the Rhode Island Sierra Club, David Veliz, chair of the Sierra Club’s Environmental Justice Committee and director of the Interfaith Coalition to Reduce Poverty, said lead poisoning is “one of the biggest environmental justice hazards impacting our children and community.”

Children can get lead poisoning by eating lead chips from flaking window sills (they need to be stripped to the wood to remove all of the lead paint) or other long-ago painted areas that are peeling; ingesting or breathing dust that contains lead; drinking tap water that contains lead from old pipes; eating fruits or vegetables that have lead on them from the soil around pre-1978 homes; and/or from some toys and household products.

Lead exposure can affect nearly every system in the body and, because such exposure often occurs with no obvious symptoms, it frequently goes unrecognized.

If a person is exposed to high levels of lead over a short period of time or exposed to lower levels over time, they may experience abdominal pain, depressed, distracted, tired, forgetful, irritable, and/or pain or tingling in the hands and feet, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Lead poisoning can also expose children to brain and nervous system damage, slowed growth and development, and learning and behavior problems — e.g., reduced IQ, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, juvenile delinquency, and criminal behavior.

A 2016 paper titled “Lead exposure and violent crime in the early twentieth century” studied the effect of cities’ use of lead pipes on homicide between 1921 and 1936. The authors found lead water pipes exposed entire city populations to much higher doses of lead than have previously been studied in relation to crime. Their work suggested that the use of lead service pipes considerably increased city-level homicide rates.

“A growing body of evidence in the social and medical sciences traces high crime rates to high rates of lead exposure,” according to the paper. “Scholars have shown that lead exposure and crime are positively correlated using data on individuals, cities, counties, states, and nations.”

A 2017 working paper, using a dataset linking preschool blood lead levels, birth, school, and detention data for 120,000 children born between 1990 and 2004 in Rhode Island, analyzed the impact of lead on behavior, most notably in regards to school suspensions and juvenile detention.

The authors found a one-unit increase in lead increased the probability of suspension from school by 6.4% to 9.3% and the probability of detention by 27% to 74%.

Lead exposure in early childhood has also been linked to diminished cognition, poor impulse

control, inattention, and aggressive behavior. Exposure can also lead to hearing and speech problems, anemia, and seizures. The impacts are irreversible.

“Lead exposure can cause long-term effects that can be hard to identify as related to lead poisoning, like trouble concentrating, difficulty in school, difficulty with impulse control, irritability, other sorts of behavioral challenges and learning difficulties,” Devra Levy, community organizer for the Providence-based Childhood Lead Action Project, told the online audience during the Sierra Club’s March 29 forum. “It’s most dangerous for kids under 6 because their systems are developing … but also because kids crawl around and put their hands in their mouths.”

She noted lead poisoning is a “classic example of an environmental justice issue that has been tied up with race and class for decades.”

The use of leaded paint peaked in the 1920s and gradually fell off until its ban in 1978. At its peak in the ’70s and before its use was prohibited in 1986, leaded gasoline emitted about 250,000 tons of lead annually into the environment.

Since it does not break down, most of the lead ever produced remains in soil, dust, and other environs. The odorless and colorless metal can only be detected through chemical analysis.

“The history of lead is really rooted in racism and exploitative advertising,” Levy said. “In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, society and doctors were catching on that lead was dangerous. Companies knew that lead was dangerous to kids from very early on, but companies pushed it really strong, even though there were other options available.”

She noted business interests even advertised to children directly. She showed a slide of a Dutch Boy children’s book titled The Dutch Boy’s Lead Party. Levy said the book was published at a time, in 1923, when lead-paint companies knew their product was poisoning and killing children.

“As those dangers became more well known, paint companies were on the record blaming Black and Latinx parents for lead poisoning, saying it was the result of messy homes or poor parenting,” Levy said. “Attempting to shift blame off of the companies who were really promoting the product.”

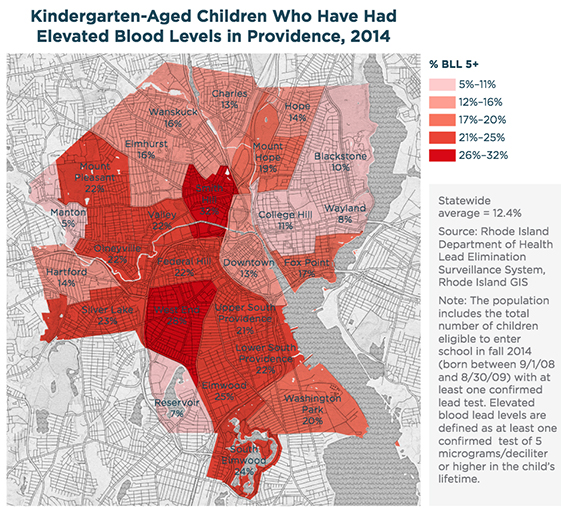

Much of Rhode Island’s lead poisoning is concentrated in the poorer and less white neighborhoods in the four cities previously mentioned.

For example, in the Providence neighborhood of Olneyville 14% of children younger than 6 had elevated blood lead levels, some of the highest in the city, according to a DOH community assessment conducted a decade ago.

Citywide, lead poisons 10% to 30% of Providence’s kindergarten-aged children, depending on the neighborhood, according to the city’s Climate Justice Plan.

The 88-page report, which was released in 2019, also notes that city neighborhoods near polluting industries and highways have the highest rates of poverty and non-white populations. These same low-wealth communities also have the highest lead poisoning and asthma rates in the state. They also have fewer trees compared to wealthier and whiter neighborhoods.

Paint chips

More than 70% of Rhode Island’s housing has potential lead hazards that can poison children, according to DOH. The most prevalent lead exposure in Rhode Island comes from lead-based paint and paint dust found in dwellings built before 1978.

The problem can only be solved with a strong commitment from municipal and state officials, funding, and the proactive enforcement of Rhode Island’s Lead Hazard Mitigation Act, according to environmental justice advocates.

This past spring, for example, Cranston City Council member John Donegan proposed the Safe Occupancy Ordinance, which would require landlords to get a certificate for safe occupancy for each dwelling unit before they could rent the space.

To obtain the certificate, a landlord would need to have the unit(s) inspected; maintain the unit(s) in compliance with state and local housing codes; proof of a Lead Safe Certificate; and pay a $100 fee per unit. The fees collected would be used to create a permanent source of funding to support the development, repair, and rehabilitation of low- and moderate-income housing.

In February, after a third child tested positive for elevated lead blood levels, enforcement action was taken against two Providence landlords who own and operate a property built in 1900 that has had multiple cases of lead poisoning in children. A Rhode Island Superior Court judge ordered the owners to hire licensed professionals to complete lead hazard remediation at an apartment on Wealth Avenue within seven days of the issuance of the court order.

Earlier this year the attorney general’s office also asked for a preliminary injunction compelling two defendants to immediately remediate the lead hazards at their rental property in East Providence. Last November, Attorney General Peter Neronha had sued the defendants for long-standing lead violations following the childhood lead poisoning of a tenant. A repeat inspection by DOH in late December 2021 confirmed that the lead hazards were still present.

In May, the attorney general’s office filed lawsuits against three landlords for noncompliance with state lead poisoning prevention laws at rental properties on Garden Street in Pawtucket and Ward Street in Woonsocket. Neronha said significant lead hazards were found in the homes.

Earlier this month the attorney general’s office filed lawsuits against five landlords for noncompliance with state lead poisoning prevention laws. All of the lawsuits involve properties where significant lead hazards were found and a child was determined to have lead poisoning.

“Landlords who prioritize profits over the health of children and the risk of lead poisoning will find themselves facing a strong response from our office,” Neronha said in the press release announcing the most-recent lawsuits. “The allegations against the defendants here, and against those in other cases we have brought, are that a landlord was notified multiple times that there is a lead hazard on their property, that a child living there was lead poisoned, and that they did nothing about it. These circumstances are unacceptable, the health consequences are serious, and strong action by this Office is warranted.”

Since last fall the attorney general’s office has filed 17 lawsuits against landlords who have failed to fully address serious lead violations on their properties. (The state maintains an online list of lead certifications, violations, and licensed lead professionals.)

The CDC currently uses a blood lead reference value of 3.5 micrograms per deciliter to identify children with blood lead levels that are higher than most children’s levels.

Children of color who live in urban areas are at the highest risk of poisoning caused by lead-based paint. A CDC study determined that 11.2% of Black children and 4% of Latino children are poisoned by lead paint, compared with 2.3% of white children.

While the United States put restrictions on the lead content of paint in 1977 and banned it a year later, leaded paint was never systematically removed from old buildings.

In 2020, the CDC estimated that about 3.6 million families in the United States were at risk of lead poisoning because of the presence of lead-based paint in their homes.

Lead in water, however, is the part of this public health problem that is typically overshadowed by the more publicized aspects of lead-laced paint and lead-containing soil and dust. The water problem routinely takes a regulatory back seat, especially when it comes to rental units. For instance, leases require a lead disclaimer in the case of paint, but not water. There is also no legal requirement for landlords to regulate lead in water, or even inform their tenants of a potential problem.

While Rhode Island health officials have noted other sources are bigger contributors to elevated levels of lead in children’s blood, they do not discount the threat posed by lead in drinking water, especially when no level of lead exposure is considered safe.

Leaded water

When the systems of lead pipes that run under Providence and the state’s three other core cities were first installed, many people didn’t know about or understand the dangers of lead poisoning. As a result, lead remains the primary connection for water running to older homes. The fix is complicated, and expensive, as copper piping is the replacement.

And while the use of lead solder for drinking water pipes was banned 35 years ago, there is no law that requires these pipes to be replaced. Rhode Island, like New England’s five other states, has old housing stock with plenty of lead plumbing.

The number of lead pipes carrying water to homes in all 50 states ranges from 9.7 million to 12.8 million, yet most states do not track this public health threat, according to a 2021 analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

In an effort to characterize the scope and geographic reach of this health problem, the NRDC requested estimates of total lead water pipes from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Just 10 states and the District of Columbia were able to provide the organization with statewide lead pipe estimates. Another 10 states, including Rhode Island, failed to respond, despite at least three requests for the data.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has found lead-heavy water systems are disproportionately impacting people of color and low-wealth communities, putting them at greater risk of lead exposure and elevated blood lead levels.

A 2020 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) examined Providence Water’s service line data and reported that people of color, renters, and low-wealth families are more likely to live in homes with lead service lines.

Providence Water’s system is one of the largest in the country to routinely exceed federal lead standards. Federal law requires that if more than 10% of sampled high-risk homes have lead above 15 parts per billion (ppb), water utilities must immediately notify customers and take additional action, such as preventing corrosion that causes lead leaching.

Providence Water, however, is hardly the only utility battling leaded water. Since 2013, about 1,400 water systems nationwide have reported excessive lead levels of more than 15 ppb at least once, according to the EPA. Among the cities that have faced this problem are Fall River and New Bedford, Mass.

For the past decade Providence Water has been working to replace these lines. The utility’s service area contains an estimated 27,500 lead service lines. In 2012, a panel consisting of six nationally recognized leaders in corrosion control was convened.

This advisory panel consisted of: Marc Edwards, a civil engineering/environmental engineer at Virginia Tech who helped bring the Flint, Mich., water tragedy into focus (40% of Flint’s population lives below the poverty line); Abigail Cantor, a chemical engineer specializing in water quality investigations; Stephen Estes-Smargiassi, director of planning and sustainability at the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority; Daniel Giammar, professor of environmental engineering at Washington University in St. Louis; Michael Schock of the EPA’s National Risk Management Research Laboratory; and David Reckhow, a professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

They hypothesized that the increased lead levels are being caused by iron corrosion within the many miles of unlined cast-iron distribution piping in the utility’s distribution system.

Critics of Providence Water’s replacement effort, however, have maintained this health-protecting work is taking too long to complete and allege the way it is being done has disproportionately raised the risk of lead exposure for Black, Latino, and Indigenous people.

In a complaint filed with EPA in early January, five advocacy groups claim Providence Water violated federal regulations and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because the utility requires property owners to pay to replace lead pipes running from the curb to the home.

“All families deserve lead-free drinking water, regardless of race, class, or any other factor,” Laura Brion, executive director of the Childhood Lead Action Project, is quoted in the Jan. 5 press release that announced the filing of the complaint. “Right now, ProvWater will only fully replace lead pipes for property owners with enough money to pay out of pocket or take out a loan. This amounts to obvious race and class discrimination and needs to stop.”

When a service line is only partially replaced, the section from the water main to the curb stop, it can raise the level of lead in the water for several months because the work disturbs the remaining private-side line that runs from the curb to the house, increasing the release of lead particulates and resulting in higher lead levels in the short-term with no long-term reduction in lead.

The 43-page complaint notes Providence Water’s process to replace lead service lines (LSLs) generally happens as part of its water main infrastructure rehabilitation projects during which the utility replaces only the portion of the LSL that runs from the water main to the curb.

“To replace the entire LSL, Providence Water requires homeowners and landlords to pay for replacing the private-side LSL, at a cost of up to $4,500 through a 10-year, 0% interest loan program,” according to the complaint. “When these customers lack the resources to pay or borrow money to pay for the private-side LSL replacement, Providence Water proceeds with a partial LSL replacement, putting residents at a higher risk of lead exposure from drinking water.”

The Childhood Lead Action Project, the South Providence Neighborhood Association, Direct Action for Rights and Equality, the National Center for Healthy Housing, and Environmental Defense Fund claim this practice creates disproportionate health impacts.

“This is true because Black, Latinx, and Native American residents of Providence Water’s service area tend to have less of an ability to pay for a full LSL replacement and are more likely to rent their homes compared to their white and often wealthier counterparts,” according to the complaint. “An EPA environmental justice analysis of its recent LCR [Lead and Copper Rule] revisions found that ‘household-level changes that depend on ability-to-pay will leave low-income households with disproportionately higher health risks.’”

In the complaint, the five groups note that 42% of participants in a zero-interest loan program to finance lead pipe replacement were in Providence’s wealthiest zip code, which is home to about 9% of the population served by Providence Water.

They have asked EPA to direct Providence Water to offer full service line replacement at no cost to customers and to track the impact of lead replacement programs on residents by race.

Dangers of lead

Lead pipes can contaminate drinking water, which can cause developmental delays in children, put fetuses at risk because lead can cross the placental barrier, and is harmful to all people regardless of age and health status.

Providence Water’s lead levels routinely exceed the EPA’s standard for action. The utility serves Providence, Cranston, Johnston, North Providence, and parts of Smithfield.

Providence Water has exceeded EPA’s lead action level under the Lead and Copper Rule — the regulations implementing the Safe Drinking Water Act for lead in drinking water — every year since 2006, with the exception of 2015.

The January complaint filed by the advocacy groups notes the “utility was recently ranked second-worst on a national priority watch list for lead.” It also notes homes serviced by its lead service lines “routinely have water samples with lead levels above 100 parts per billion.”

“Full replacement of LSLs is the only way to eliminate this source of lead exposure from drinking water,” according to the complaint.

Providence Water, which supplies about 60% of Rhode Island with its drinking water, has noted it takes the issue of lead seriously. The utility is working with the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank to maximize federal funding earmarked for the removal of lead service lines, saying the program will be designed to prioritize replacements in low-wealth neighborhoods.

Since 2012 Providence Water has raised the pH of its water — adding phosphorous is a common practice — to initiate reactions that minimize lead corrosion. When water interacts with buildup inside pipes, it results in the increased or decreased leaching of lead.

In January 2021, the EPA awarded Providence Water a $6.4 million grant to fund the replacement of some 1,400 private-side lead service lines.

“This work will reduce lead exposure via drinking water for an estimated 3,700 people,” according to the grant application. “All of these lead service line replacements will be conducted within opportunity zones as defined by the United States Department of Treasury and ‘disadvantaged communities’ as defined by the state of Rhode Island.”

In April, water main and service line construction work began in Providence’s Washington Park and Charles Street neighborhoods. The work included the rehabilitation of some 63,100 linear feet — about 12 miles — of mains and the replacement of public and private lead service lines, according to Providence Water. As a result of grant funding secured by Providence Water, the utility said there was no cost to income eligible customers — household incomes of less than $58,000 — to replace private-side lead service lines.

Letters from Providence Water warned this construction could cause a surge in lead levels in residents’ drinking water, writing: “You may experience a TEMPORARY increase in lead levels in your water from particles dislodged during the lead service line replacement.”

The Washington Park and Charles Street projects were part of Providence Water’s Infrastructure Rehabilitation Program. About $140 million has been invested to replace or reline more than 116 miles of water main since the program began in 1996, according to Providence Water.

“In the interest of public health and environmental justice,” Senate Majority Leader Michael McCaffrey, D-Warwick, introduced the Lead Poisoning Prevention Act during this year’s General Assembly session.

McCaffrey said the legislation would give “new urgency to the replacement of antiquated, unsafe lead pipes.”

The proposal would have created a lead water supply replacement program for both public and private service lines, with a requirement that all impacted lines are replaced within 10 years. Financial assistance would have been provided through the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank, including no-cost options for property owners.

It would have required Rhode Island’s 30 water utilities to conduct a comprehensive inventory of lead water lines in their service areas. It would have also established new notification and reporting requirements for utilities to ensure transparency in the identification and replacement of service lines containing lead.

McCaffrey noted that with “unprecedented financial resources available to Rhode Island through the federal infrastructure bill and the American Rescue Plan Act, the present moment offers a rare opportunity for us to accelerate efforts to eliminate lead in water systems.”

“Access to safe, lead-free drinking water should never depend on someone’s ZIP code or economic status,” he said. “No family should have to fear that their home, an environment that should be safe and nurturing, may be poisoning their children.”

The bill passed the Senate on June 14 after being revised via a floor amendment. The legislation failed to make it out of the House before the session ended.

This story was funded by a grant by the EJMP Fund for Philanthropy to examine the intersection of the environment and public health.

To view the series, click here.

Many years ago, working with a mental health agency I made a few strategic phone calls. to folks associated with the ACI. it was quite clear that many of the people in the ACI had lead poisoning . If we want safer communities one of the most important things to do is get the lead out.

I know this handout https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/documents/fight_lead_poisoning_with_a_healthy_diet_2019.pdf will not remove the threat of lead poisoning, but it can help reduce the toxic levels in the body if combined with flushing the water faucet before use, when cooking or washing produce and or filtering the water and lastly not boiling the water for cooking purposes https://jwcwater.org/water-quality/lead/ . I personally filter water for use in my kitchen and for drinking.