Blasting Near Aging Pipeline to Build Proposed Solar Project Makes Nearby Neighbors Nervous

March 31, 2023

CRANSTON, R.I. — A few days before Christmas in 1986, Walter and Clara Lawrence were offered a deal they simply couldn’t accept. It was insulting, but not quite as bad as the offer their neighbors received.

Two representatives from the Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co., sitting at the couple’s dining room table, offered the Lawrences a one-time payment of $10 for the right to dig a 50-foot-wide, 700-foot-long trench in their yard to bury a natural gas (methane) pipeline, according to Walter. He said the company also offered $4,000 to cover all damages to the property, but noted Tennessee Gas in its own incomplete appraisal of damages estimated those costs to be about $23,000. Before taking the Lawrences to court, the company’s final offer was the one-time $10 payment and $6,872 for damages.

The Moreaus, the Lawrences’ neighbors across the street, were allegedly offered a fruit basket, for a perpetual easement on their property for the pipeline and a metering station in the southeast corner of their land. The Moreaus — the late Judy and Robert — told the company their property, the historic Thomas Baker Farm, dated back to the pre-Revolutionary War era and was entitled to protection under the National Historic Preservation Act.

Tennessee Gas also offered to buy both properties, according to court documents.

Both couples declined the offers. Neither wanted to move — the Lawrences have lived at their current Natick Avenue address since 1970; Clara has lived on the historic street since she was 9 — and neither wanted a fossil fuel pipeline running under their property. Walter noted he and Clara — both 87 now — would still have to pay taxes on the 50-foot-by-700-foot right-of-way with limited use. He also noted he spoke with at least five local insurance agencies who told him an ordinary homeowners policy would not cover liability should an accident happen.

“Why should I go in a risk pool to cover any accident that might happen if this thing blows up,” Walter said.

The two neighborly couples would spend the next several years fighting TPG’s favored route for the pipeline project. Their fight took them to courts in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C. They had to travel to the District of Columbia to find a law firm with the expertise to handle such a case.

The Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP) is a network of methane pipelines that starts in southern Texas and ends in northeastern Massachusetts, cutting through Connecticut and Rhode Island. The 11,900-mile-long system is operated by the Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co., a subsidiary of Kinder Morgan. The Houston-based oil and gas giant operates 83,000 miles of pipeline and 143 fuel terminals, and is one of the nation’s largest shippers of crude oil, gasoline, and methane. In 2021, Kinder Morgan claimed $16.6 billion in revenue and $70.4 billion in assets.

After the Lawrences and the Moreaus rejected TPG’s offers, the company took the two western Cranston couples to court under the power of condemnation to seize private property for public use.

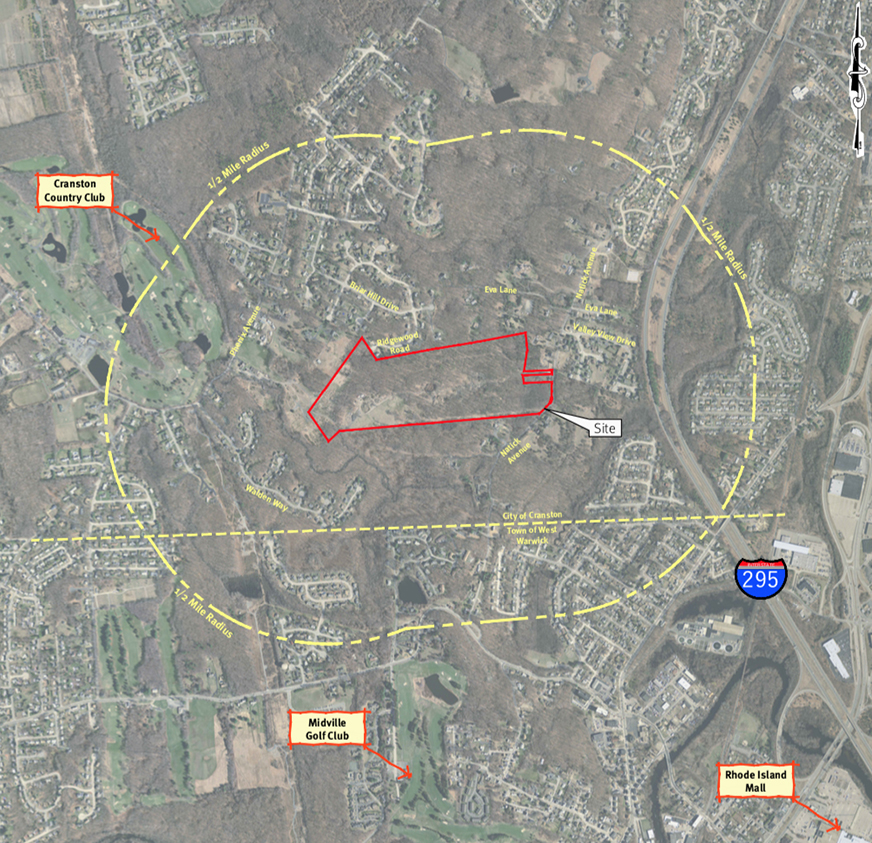

Thirty-plus years later, an 8-megawatt solar array on 62 acres of open space is planned for the Natick Avenue property under which the Tennessee Gas Pipeline runs.

Residents are concerned the disturbance of land and topsoil and the removal of vegetation, including trees, on a sloped property in order to build a utility-scale ground-mounted solar installation will exacerbate stormwater runoff and erosion and increase sedimentation in nearby wetlands.

They are also concerned that the proposed blasting of ledge to build the solar project will damage the three-decade-old pipeline, especially after how the permitting process for the pipeline unfolded.

“In the process [of building the pipeline], they pierced a wetland and violated it,” said Drake Patten, who has lived across the street from the pipeline and the Lawrences since 2014. “And there was a pretty big case that resulted from that. That piece of the story is something that Walter and Clara can speak to in great detail.”

The longtime couple recently did just that, for two-plus hours with this ecoRI News reporter at the home of Patten, and her husband, Wright Deter. The dining room table we sat around was covered with manila folders filled with documents, maps, and photographs. There was even a VHS tape — one of 15 videos Walter shot during the construction of the pipeline just beyond his property line.

Solar flare

Residents living near the gas pipeline, such as the Lawrences and Patten and Deter, who own the 48-acre Hurricane Hill Farm, the former property of the Moreaus, have spent the past five years fighting the proposed Natick Avenue Solar project, which is across the street from Patten and next door to the Lawrences. Solar panels would cover about 30 acres, or roughly half of the property.

Patten supports renewable energy development, but, like many others in the state, favors the responsible siting of industrial-scale projects on already-developed areas that are vacant, underused, or surrounded by asphalt — not on open space, farmland, or forestland, whether across the street or across the state.

The applicant (Natick Solar LLC) and developer (Revity Energy LLC, formerly Southern Skies Renewable Energy) started the application process to build the solar facility off Natick Avenue in 2018; the project received master plan approval a year later. The property is owned by Phenix Avenue resident Ronald Rossi.

“The proposed Natick Avenue project, and others like it in the city, were made possible after the City Council changed the zoning rules, mostly impacting the western part of the town, to allow solar panels by right in rural residential areas,” Patten said. “Facing backlash about approved projects, the council then approved a moratorium on new projects and eliminated solar installations entirely as a zoned use.”

In May 2022, citing procedural issues with public comment, Superior Court Judge Netti Vogel ruled, in a lawsuit brought against those behind the solar project by Patten, Deter, the Lawrences, and others, that the project’s master plan must go before the Planning Commission again.

The Natick Avenue Solar project is expected to be on the Planning Commission’s April 19 agenda.

Rerouted pipeline

The construction of the Rhode Island section of the Tennessee Gas Pipeline was finished in the early 1990s. The preferred route, the one the company tried to buy for a sawbuck and some fruit, was eventually rerouted — in large measure because of the tenacity of the Lawrences and Moreaus.

In November 1986, Tennessee Gas applied to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) under the provisions of the Natural Gas Act for a certificate of public convenience and necessity to condemn certain property to build and operate a pipeline from its Massachusetts facility to a termination point in Cranston, according to a 1993 lawsuit.

Nearly three years later, in May 1989, FERC approved the company’s initial pipeline route. Upon learning of this order, the Moreaus sought to intervene in the FERC proceedings. During this same period, Tennessee Gas sought to have the 1989 order modified to include the revisions it had made to the pipeline route in 1988. Before FERC could act on the company’s motion to amend, Tennessee Gas filed an action seeking a condemnation order for that portion of the Moreau property needed for the pipeline construction.

In September 1990, FERC granted a Tennessee Gas motion to amend the pipeline route. This modified route went around the Lawrence property and through that of the Moreaus. The Moreaus were granted a rehearing by FERC. In November 1990, U.S. District Court in Rhode Island issued an order condemning a portion of the Moreau property. The Moreaus appealed to the First Circuit Court of Appeals.

A year later, Tennessee Gas notified the Moreaus that it was seeking approval of another change in the pipeline route which would reroute the pipeline around their property. FERC approved the company’s second revision to its pipeline route, and in April 1992 Tennessee Gas dismissed its condemnation actions against the Moreau and Lawrence properties. Tennessee Gas then took the Lawrences and Moreaus to court seeking nearly $1.5 million to cover the company’s legal costs. The court ruled against the Kinder Morgan subsidiary.

The couples’ doggedness came at a considerable cost, however. “Just about our life savings,” Walter said. Clara nodded in agreement, saying, “A lot. Quite a lot.”

The Lawrences began the search for representation in Rhode Island. One law firm wanted $10,000 “just to look into the situation,” Walter said.

The Lawrences were eventually put in touch with Simons & Simons, a Washington, D.C.,-based law firm led by the husband-and-wife team of Morton and Barbara Simons. The attorney couple asked for a $300 deposit — the Lawrences and Moreaus split the cost.

Wanting to meet their would-be attorneys in person before hiring them, the Lawrences drove 400 miles to D.C. in their Dodge Caravan to deliver the deposit in cash. They drove down on a Sunday.

At the end of their journey to Linnean Avenue in D.C., where the attorneys lived and worked, it became a confusing jumble of roads bisected by a park and Walter got lost. It was the late 1980s with no mobile phones or Google maps, so Walter stopped and asked for directions.

“I see this fella standing on the sidewalk outside of a bar, so I asked him,” Walter recalled. Soon there was a map on the hood of the Caravan and the bar patron is telling Walter he is an Episcopalian and a little drunk. He tells the couple to follow him.

“So here I am, a Baptist, being led by a drunk Episcopalian,” Walter said. “We follow him … and he stops and he motions like that [Walter starts pointing with his right hand]. Down there.”

The Lawrences got a hotel room down the street from the small law firm and visited with Morton and Barbara Simons the following morning.

Permit problems

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management approved a permit for the TGP pipeline on Aug. 27, 1991, but then realized nearly a year later that wetlands had been altered, according to the paperwork in the Lawrence files. There are about 7 acres of total wetlands on both sides of Natick Avenue in the area where the pipeline is laid.

On July 15, 1992, DEM served Tennessee Gas with a notice of suspension of permit and order. Two inspections, one in early June of that year and the other later that same month, found “that during construction of the pipeline, TGP had altered certain freshwater wetlands. Those “areas were not shown or represented on the revised plans on which [DEM] partly based its issuance plans.”

The notice told TGP to “cease and desist from undertaking any additional alterations or work in furtherance of the permit.” TGP appealed. The courts eventually ruled in the company’s favor. The pipeline was already in operation.

The Lawrences claim the alternate route, which runs close to their property line and is about 10 yards away from their home at one point, was never advertised and no public comment was ever accepted.

The 36 miles of 20-inch and 16-inch-diameter welded steel pipeline begins in Sutton, Mass., and runs south through the Massachusetts towns of Northbridge, Douglas, and Uxbridge, where it reaches Rhode Island and goes through Burrillville, North Smithfield, Smithfield, and Johnston before ending in Cranston at the West Warwick border, according to the project’s November 1988 environmental assessment.

The 75-page assessment notes pipeline “padding consisting of a 6-inch layer of sand or gravel, crushed rock, or screened trench soil, would be placed on the trench floor to protect the coating and support the pipe. Topsoil from the ROW [right-of-way] would not be used as padding.”

Walter, whose career was spent in the construction trades, watched closely as the pipe was laid behind his house, taking photos with his camera and even buying a clunky videotape recorder to document the work. He believes those guidelines weren’t properly followed. He noted workers were less than thrilled by his presence.

His photo collection shows that neither gravel nor sand were put down to protect the sections of pipe. His pictures show welding rods and rocks left in the trenches. They show stones under and around pipes and welded joints. One photo shows where a rock banged against a section of pipe, leaving the coating scraped. He believes removed topsoil was in fact used as trench padding.

Walter called city officials, his local representatives in the General Assembly, DEM, and the state’s Public Utilities Commission (PUC) about his pipeline concerns. He was routinely told he needed to call someone else.

By the time a PUC official came to his house, about a month later, the pipeline was completely buried. The official showed up with a guest.

“He had a woman with him. She was all dressed up, had high-heeled shoes … they come into my yard and he says, ‘I’m here to inspect a pipe for the PUC,’” said Walter, who recalled the man’s name. “She grabs his hand and they walk down from the house. They get to the wall [an old stone wall], they climb over — she’s got high heels on — and the thing is all mud because it had been raining and it’s a wetland and she’s walking through it with him hand in hand. He says there’s nothing wrong with it. Well, how can he see the pipe?”

A 1992 Providence Journal-Bulletin story reported that the PUC was investigating a resident’s complaint about how the pipeline was buried. The PUC gas safety technician who visited with the Lawrences told the newspaper he expected the agency to require Tennessee Gas to unearth part of the line so officials can make sure the fill complies with state and federal standards.

Walter said the unearthing of the pipeline to check that work never happened.

The Lawrences’ stories regarding what they say was a rushed effort to the lay the pipe has Patten, Deter, and other nearby neighbors worried about the construction of the proposed ground-mounted solar installation above the aging fossil fuel infrastructure.

“They’re going to be blasting next to the pipeline and that concerns us,” Patten said. “Obviously, we were talking from our neighborhood because that’s what we know, but we understand this pipe runs across the state. So were these conditions mismanaged everywhere?”

Lack of class

The U.S. Department of Transportation, through the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, uses either Location Class or High Consequence Area to describe places where pipelines are located.

A Kinder Morgan Developer Handbook published in August 2021 addresses the potential impact of blasting near its pipelines.

“Blasting can profoundly impact our pipelines. Please forward any proposed blasting activities within 1000 feet of our pipeline, allowing two weeks for review and approval,” according to the handbook. “If the blasting will occur within 100 feet, you will be required to hire a blasting inspector with seismograph equipment on site during your blasting activities.”

Neighbors are concerned a lack of communication between all the entities involved regarding the possible blasting of the site to install solar panels will compromise the pipeline below. They are also interested in finding out what class of pipeline runs through their neighborhood.

Gas pipelines are classed based on where they are located at the time that they are laid. Patten said she has been trying to obtain that information but has been repeatedly told it’s not available to the public.

“Because they are classed at the time when they go in, it’s based on what’s there,” Patten said. “At the time, western Cranston was rural. We hadn’t had the land rush that we have now. We don’t know what the class of pipe is that’s going through the neighborhood.”

Cornell Law School notes a pipeline operator must have records that document the current class location of each gas transmission pipeline segment and that demonstrate how the operator determined each current class location.