Lifelong Warren Resident Captures Palmer River’s Wildness

But a changing climate is stressing vital coastal marshes along the river and in the mid and upper reaches of Narragansett Bay

July 12, 2021

WARREN, R.I. — Shrouded in morning fog, the Palmer River appears peaceful, vibrant and unspoiled. Bufflehead ducks dive for food and black-capped chickadees forage in the brush. The marsh vegetation is healthy and free of docks or houses leaning over the water. Only the din of nearby traffic serves as a reminder of the inevitable spoiling of natural places.

This 5-mile eastern edge of the brackish river has largely been spared from development, thanks in large part to high-voltage power lines that run parallel to the shore, about 50 yards from the river’s edge. The inner marsh, or high marsh, has pockets of forested swamp, the natural habitat. Other portions are flat and muddy cow pasture. A golf course and industrial parks protrude into the wetlands’ undefined landward edge.

This delicate coastal zone has been a lifelong playground for Butch Lombardi. The Warren native spent the late 1940s and ’50s exploring the river with friends and dip netting for blue crabs with his father. His family lived in a two-story, two-family home at the foot of the river, a busy commercial street outside their front door. Belcher Cove — the neighborhood’s shared backyard — was visible from his bedroom window.

“Somebody always had a boat,” Lombardi recalled. “We were always near the water, on the water or in the water.”

Lombardi and his childhood friends regularly explored the river in a 12-foot motorboat. Three Trees Island, now called Tom’s Island, was a frequent destination. Today, the trees are gone and the tiny island has shrunk and been bifurcated by higher water levels and receding grasses. But the overall setting has changed subtly over the decades.

As a phone company technician for 31 years, Lombardi repaired equipment across New England, in places where he now photographs wildlife such as Block Island and Nantucket, Mass. In retirement, he has become an accomplished wildlife photographer specializing in capturing images of avian inhabitants in coastal communities.

Birds of prey, such as osprey and bald eagles, weren’t around when he was a kid, but have slowly reappeared after the ban on the insecticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) in 1972. Some 30 nesting platforms have been built within the Palmer River watershed during the past decade to welcome these seasonal visitors.

Other wildlife has prospered, such as diamondback terrapins, which nest each summer along the inland sand of Warren and across the river in Barrington.

But the river is facing threats. Pollution halted shellfishing and aquaculture in 1992. Monitoring by environmental agencies in Rhode Island and Massachusetts and by the Environmental Protection Agency indicates the problem stems from high amounts of fecal coliform bacteria from farms upstream in Massachusetts. Runoff from major roadways, such as Interstate 195, which crosses the Palmer River north of Warren, also contributes to elevated nutrients.

Residential and commercial development in Barrington and in Seekonk, Swansea and Rehoboth, Mass., have shrunk the watershed’s natural pollution control. Some 600 acres of forest and farmland in the watershed were lost to development between 1995 and 2018. None of the Massachusetts municipalities have public sewer systems. The environmental agencies, however, say pollution-control plans adopted by farms will lessen the amount of harmful runoff.

But the sanctuary is transitioning in other ways. The salt marsh floods more often, disrupting the nesting of the saltmash sparrow, a species expected to go extinct within 20 years. The higher water level and tides impede the marsh from draining. Stranded pools and puddles erode the vegetation, leaving patches of muck in place of estuarine habitat.

Wenley Ferguson, Save The Bay’s director of habitat restoration, called marsh erosion in mid and upper Narragansett Bay, such as along the Palmer River and in Hundred Acre Cove in Barrington, “pretty significant.”

“We have noticed widening of creeks and ditches and marsh edge erosion over the past decade,” she wrote in an email. “There has been a significant increase in fiddler crabs as well in the last 8 or more years, taking advantage of the new niche of die off zones on the marsh platform. These area are easier for them to burrow in than when there is healthy marsh. The peat is now riddled with burrows.”

Photographic eye

Lombardi’s passion for nature and photography grew from his time in Boy Scouts. He started taking photographs in 1968 using the Bellows camera his father brought home from World War II.

Born in 1946, Lombardi is at the lead edge of the Baby Boomer generation. The surge in population created a wave of new construction. Habitat was lost as pollution grew. Marshes were considered nuisances and turned into parking lots, subdivisions and municipal dumps. His home on Market Street was near an active dump where trash was burned and seagulls were the dominant species.

At age 9, Lomabardi and his family moved across town, near the Warren River, which is fed by the Palmer River and flows into upper Narragansett Bay. During summers, Lombardi and his friends played in Burrs Hill Park, then swam at Warren Town Beach across the street.

In the ’50s and ’60s there was always open, dry beach regardless of the tide level. Today, high tides regularly envelop the entire beach.

“A moon tide as a kid is now a normal tide,” Lombardi said. “A moon tide now is a flood tide. On a king tide there is no beach, it’s gone. If this keeps going the beach is going to be across the street.”

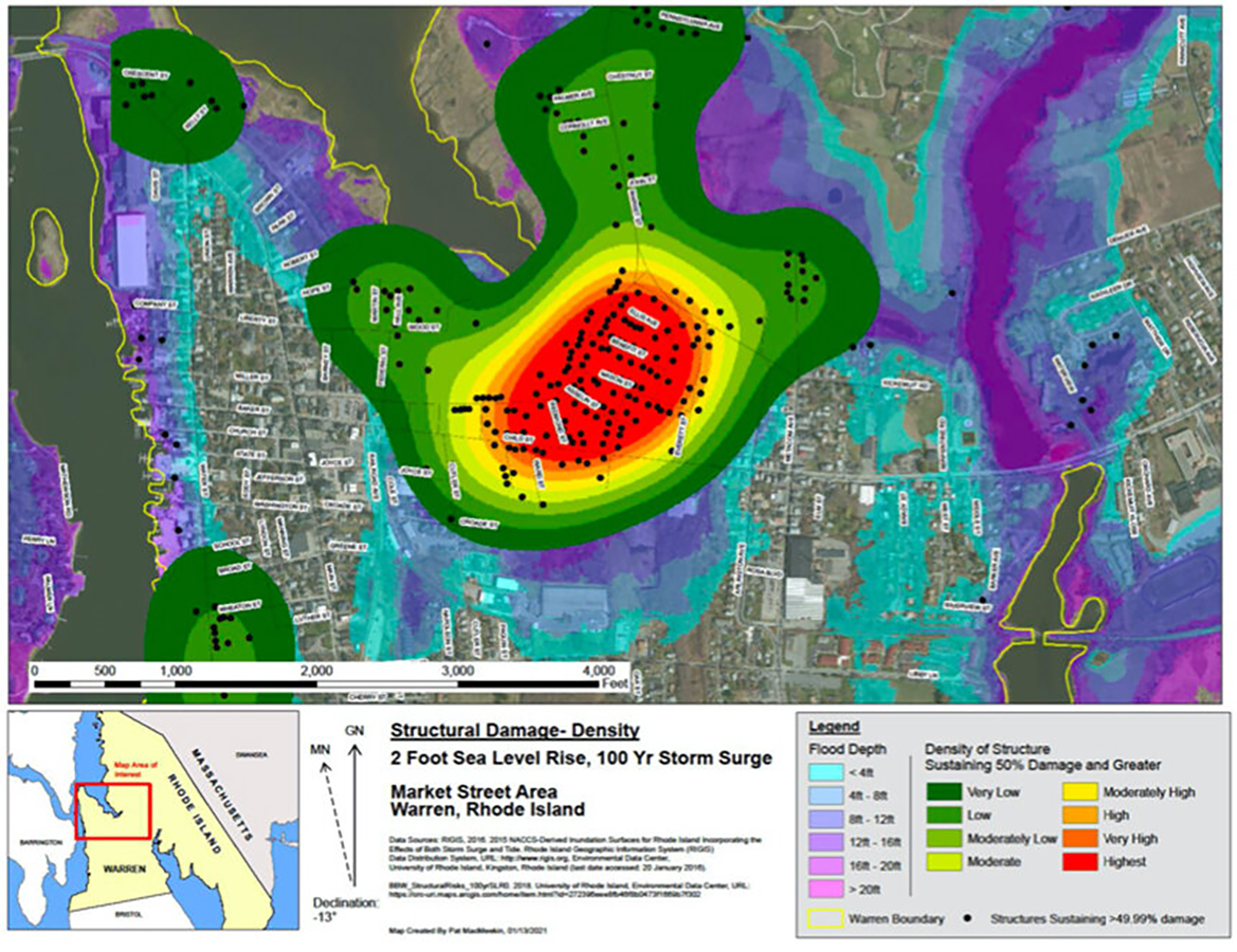

Warren, one of Rhode Island’s smallest municipalities at 11 square miles, is also one of the most threatened by the climate crisis. Its highest elevation is a mere 7 feet above sea level. The town is surrounded by water, and flooding and sea-level rise maps predict massive shoreline and even inland inundation.

Town officials are taking action to protect coastal infrastructure. The wastewater treatment plant on the Warren River was fortified against storm surges. Bioswales were built near the public beach to control stormwater runoff and flooding. Town planners were early participants in the federally funded Municipal Resilience Program.

Wastewater pump stations are being elevated and strengthened. The town plans to raise a 2-acre lot it bought next to the American Tourister Mill, preserving an iconic building that will anchor additional retail space with a waterfront walkway. The town has plans to redevelop the Metacom Avenue and Market Street areas.

But the work, so far, is slight progress toward what is needed to address a waterlogged future. Town planner Robert Rulli said the shoreline is too large to re-engineer for sea-level rise and intensifying storms.

Lombardi’s neighborhood on Market Street, Rulli noted, is one of the most at risk. Storm drains are reverse flooding during high tides and street foundations are washing away beneath the asphalt. Major damage to homes and businesses is expected from extreme weather. Flood gates were considered and rejected at the site of the former dump, which is now a park.

“That’s an area where we are not going to hold it back,” Rulli said.

He hopes to engage National Grid about protecting a substation and natural-gas transmission station next to Belcher Cove. So far, the utility hasn’t responded to Rulli’s request to talk.

The town planner is exploring compromises for residents and business such as property buyouts and scouting land for new housing. Plans have been drawn for a residential and retail development in a outdated shopping center on Metacom Avenue.

“I’m not trying to scare people but I want to be proactive and be sure we have a plan,” Rulli said.

Despite the town’s minor work done to address a massive problem, Warren is ahead of many other Rhode Island municipalities. The town partnered with Barrington in the state’s Municipal Resilience Program for projects in both communities. Rulli stressed that regional partnerships and projects are necessary to address the problem.

“Some of these things we have to collaborate on because climate change doesn’t understand borders,” he said.

He noted public support requires educating residents and other stakeholders. With help from an intern, Rulli designed maps showing probable flooding in five-, 10- and 20-year increments. The images are intended to reinforce the concepts of major structural damage and repetitive losses. He said they inform insurers, property owners and state planners of the trouble ahead.

“All in all, people are somewhat apathetic about it,” Rulli said. “There are people that get it, but it’s a small portion of the population.”

Lombardi said people don’t take the climate crisis seriously because the changes are happening slowly. But every small environmental loss, he said, has a domino effect on the environment.

“Everything that gets compromised, compromises something else. That’s what people don’t understand,” he said.

To see more stories in this series, click here.

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsRecent Comments

Leave a Reply

Your support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings

Great article on this area I live in and love.

I’m so happy we are recognizing some of the environmental problems we face, or some of us do, and are trying to address them.

It’s all about educating the uneducated and getting more people to be concerned and getting on board.

A big Salute goes out to Mr. Lombardi.

Peter Nilsen

President

Rhody Fly Rodders

America’s Oldest Saltwater Fly Fishing Club

Barrington, RI

Thank you ecoRI to Tim Faulkner for this important story. We are all interconnected in the effects that climate change is having on our communities, states, and country. Stories like this one are vital to raising awareness and for more concerned citizens to take action to help slow effects of climate change.

A very interesting and well written article thank you!

Great commentary, Butch… we all must do our best to keep God’s creation pristine.