Tree Inequity in Rhode Island is a Stark Problem

November 20, 2020

Imagine an organism that breathes through the very edges of its being. It takes in carbon dioxide and water through tiny pores and uses light from the sun to turn these into sugars. As it does this, it releases oxygen, a sort of breath of satisfaction after hard work.

Trees, when you break it down like this, are truly mind-blowing organisms. And beyond being incredible specimens of biology, they provide innumerable benefits to humans and the planet we call home.

Without them, we suffer.

In a world that is warming rapidly, with Rhode Island being one of the fastest warming places in the United States, trees can help mitigate the heat-island effect by capturing carbon and providing shade.

But in addition to mitigating climate change, trees also help with human health and well-being.

According to American Forests, a national nonprofit conservation organization formed in 1875, “trees across the U.S. absorb 17.4 million tons of air pollutants, preventing 670,000 cases of asthma and other acute respiratory symptoms annually.”

Conversely, places that lack tree canopy also tend to be the poorest, the hardest hit by the impacts of the climate crisis, and the most urbanized, making tree access a social justice one as well.

“Trees are more than just scenery for our cities,” American Forests president Jad Daley said. “They are critical infrastructure to protect people in our rapidly warming climate and are as essential for public safety as are streetlights.”

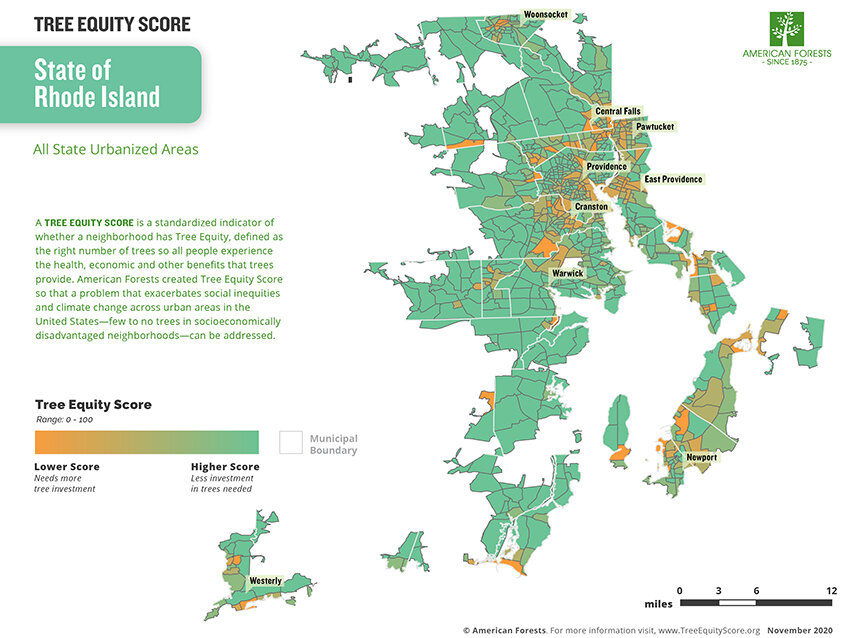

To provide tree canopy information for residents, government officials, activists, and nonprofits, American Forest recently launched an online Tree Equity Score map, which shows which areas have abundant tree cover and which are lacking. The three locations that were chosen to pilot this effort were Rhode Island, Maricopa County, Ariz., and the San Francisco Bay Area.

The project was born in 2019 in part because of the U.S. Climate Alliance, which had the backing of 25 governors, including Rhode Island’s governor, Gina Raimondo.

“When our federal government backed out of the Paris climate accord, what is now 25 governors stepped up and wanted to meet the goals set forth by that accord,” said Molly Henry, Rhode Island climate and health fellow at American Forests.

The goals included encouraging sustainability in the energy sector and creating strategies to mitigate the impacts of the climate crisis.

“Trees can be part of that, wetlands, soil carbon all those things, so the Rhode Island group identified urban forestry as our pathway,” said Henry, who is the on-the-ground coordinator for the Rhode Island Tree Equity Score effort.

Henry noted that Rhode Island was chosen to pilot the program partially because of its small size and urbanized topography.

“Rhode Island is a great place to do pilots because of the size and … at one point we described ourselves as one big urban forest because we are so urbanized,” she said. “So it seemed like a great way to test our tools and to look at tree equity from a statewide lens.”

The team at Washington, D.C.-based American Forests bought light detection and ranging (LIDAR) tree canopy data specific to Rhode Island and worked with the University of Vermont’s Spatial Analysis Lab to process the information, getting an accurate portrait of what tree canopy looks like in the Ocean State.

“The data at this point is around 18 months old, but it’s still 99 percent accurate to where tree canopies are in 2020 in Rhode Island,” said Chris David, senior director of GIS and technology at American Forests. “We want to deliver that level of resolution and accuracy nationally.

The American Forests team combined this information with Rhode Island Census data to create a complex map that shows who has access to plentiful tree canopy, who doesn’t, and what it means for human and environmental health.

The Tree Equity Score map shows tree canopy information for various municipalities in the state, and even goes as granular as various neighborhoods or census block groups. The Tree Equity Score analyzer tool for Rhode Island examines a Tree Equity Score on a deeper level, revealing the potential environmental and human health impacts of a tree planting project at the parcel level.

The discrepancies between both rural and urban and rich and poor are stark.

One portion of Providence, near Dyer Street, has a tree equity score of 49 out of 100. The block has 13 percent existing tree canopy, with a tree canopy goal of 40 percent. The demographics within this orange-colored block show 83 percent of the population are people of color and 93 percent are living in poverty.

Conversely, across the river in College Hill, numerous blocks have tree equity scores of 100, meaning they meet (or exceed) their tree canopy goals.

The program’s analyzer tool takes this concept even further, and allows users to create detailed reports for various locations across the state, compare various neighborhoods, and even adjust various inputs to see, for example, what would happen if a certain number of trees were planted in a specific location.

“It’ll tell you how much CO2 you’re pulling out of the air, what your annual sequestration will be once these trees reach maturity after 25 years, and all of these other co-benefits — stormwater infiltration, air quality, energy, cooling and heating,” David said. “So we provide estimates. It gets pretty powerful.”

Henry and other local stakeholders, such as the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, the Department of Health, and various nonprofits, hope that by having this information readily available will enable residents, activists, and policymakers to have the evidence to back up their needs.

“The biggest focus for us was trying to make this as accessible as possible, so that residents can go in and look and see what their tree equity looks like in relation to other neighborhoods and start to look at creating a movement and advocacy, to go to their elected officials and say, ‘Hey, this isn’t right,’” Henry said.

David noted that the other major goal of this project is even broader in scale: to bring this same kind of map to the rest of the country.

“This is one part of a larger strategy for us to deliver tree equity tools across the country,” he said. “This is a tool to help us achieve a larger goal.”

The word for world is forest. Ursula LeGuin

This is a really interesting study. Digging into the methodology on the website, it looks like they took some really good steps to try to account for population density in urban blocks, which was one of my first thoughts. So the patterns in the urban core should be quite revealing and definitely warrant some careful thought about what are the mechanisms of tree inequity and how to overcome them. I would say, however, that the methodology seems still to need some work outside the urban core. For example there are prominent low equity areas in Cranston, Point Judith, Exeter, and Barrington but when you look at what’s included they are the sites of the ACI, coastal dunes and marshes, Shartner Farms, and Four Town Farm respectively, so probably not just the inequity of tree distribution. Provocative study giving us lots to think about.

I seem to recall reading about this before. Was this pulled from the archives???? Meanwhile I just found this site http://www.planning.ri.gov/planning-areas/land-use/land-use.php and this one https://www.egovlink.com/public_documents300/sycamoretownship/published_documents/Planning%20and%20Zoning/Applications/Zoning%20Worksheets/Impervious%20Surface%20Ratio%20Worksheet.pdf. Have we ever thought to have municipalities re-examine the impervious surface ratio with regards to new developments? Meanwhile have you noticed how unused parking lot spaces are somehow being converted into more unnecessary fast food restaurants and ATMs? Shouldn’t we be asking for this barren landscape to be converted to green space instead of looking for more tax revenue? Wishful thinking. Have you ever noticed too how a store goes up and then no sooner it’s closes all to soon. Then it reopens elsewhere hoping for better profits without any repercussions. Why is that? Shouldn’t they be bonded to help offset the cost of abandonment as it relates to the destruction of wildlife habitat ????