Southern New England’s Contaminated Landscape Costs Plenty to Clean Up

Region’s three states work to redevelop a District of Columbia-sized heap of contaminated brownfields

February 20, 2023

Southern New England’s three states cover 17,322 square miles and a significant portion of that space has been adulterated by two-plus centuries of incineration, smelting, metal plating, textile manufacturing, etching, electroplating, and dumping.

Much of the environmental harm and public health deterioration that followed came after laws had been enacted but were often ignored and inadequately enforced.

The combination of apathy, selfishness, and greed that continues to place profit over the well-being of both nature and humans has led to polluted landscapes — the worse of those identified as Superfund sites or brownfields — often surrounded by marginalized neighborhoods that predominantly house low-wealth families and people of color. The remediation of these sites is frequently funded by taxpayers via government grants and/or bond funding, robbing budgets of money that could have been used to educate, house, and care for people to cover the expense of cleaning up after careless others.

A brownfield, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, is a property, the expansion, redevelopment or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, and/or contaminant. Brownfield sites include former factories in urban centers, mills in historic villages, and dumps in rural areas. The criteria to list a brownfield varies by state.

These properties often have certain characteristics in common: abandoned or for sale or lease; have been used for commercial or industrial purposes; and were likely reported to authorities because contamination was found.

Brownfield contamination can stem from activities that took place or conditions that arose before current ownership and operation of a property, and often as a result of lawful conduct, especially in the years before federal regulations. Others were created after the impacts were obvious, known or illegal.

The EPA’s Brownfields Program began in 1995. The agency has estimated there are about 450,000 brownfields currently in the United States.

In Connecticut, 841 inventoried brownfields encompass more than 4,200 acres, or some 6.5 square miles. Hartford, a city that is 36% Black and 46% Hispanic/Latino, leads the way with 92 brownfield sites. Bridgeport, a city that is 35% Black and 42% Hispanic/Latino, is next with 75. In both cities, the number of people living in poverty is above 20% — Hartford at 28% and Bridgeport at 23%. (The statewide poverty rate is 10.1%, while 12.7% of the state is Black and 17.7% is Hispanic/Latino.)

Darien, the richest municipality in Connecticut, with a median household income of $251,200 and a population that is 87% white, has zero brownfields. The rest of the state’s top 5 wealthiest communities — Old Greenwich, Weston, Riverside, and Westport — also don’t host an identified brownfield.

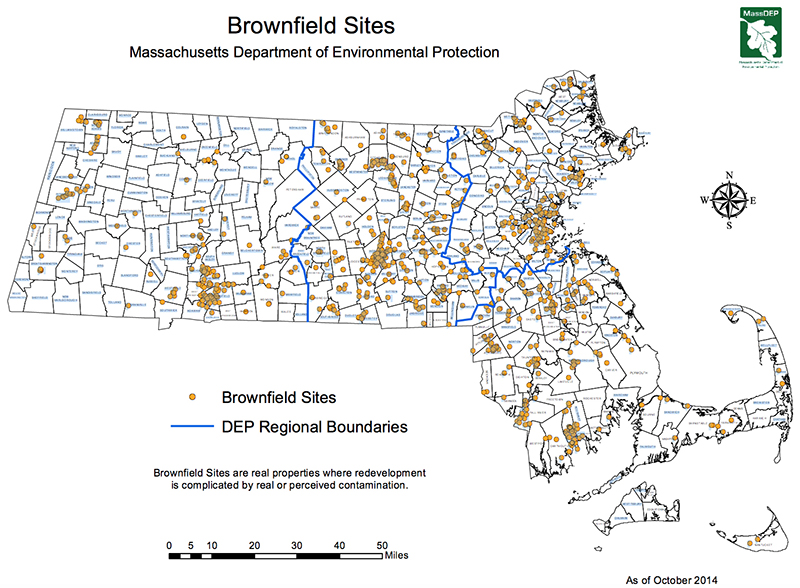

Massachusetts lists 1,278 brownfields covering 18,635 acres — 29 square miles of contaminated landscape. Among the 20 municipalities with a dozen or more brownfields are New Bedford (28), Attleboro (19), and Fall River (12). The toxic concoctions at these 59 sites include 1,2-dichloroethene, 1,2-methylnaphthalene, asbestos, coal gas waste, fuel oil, lead, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, tetrachloroethene, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and waste oils.

The two municipalities with the most brownfields — Worcester (137) and Springfield (78) — also feature significant populations of people of color, 44% and 72%, respectively, and high levels of poverty, 19.3% and 26.3%, respectively. (The statewide poverty rate is 10.4%, while 9.3% of the state is Black and 12.8% is Hispanic/Latino.)

The state’s five wealthiest Massachusetts municipalities — Dover, Sherborn, Wellesley, Weston, and Carlisle — have a combined two identified brownfields, one each in Wellesley and Weston.

Based on its remediation regulations, Rhode Island lists about 2,800 brownfields totaling some 22,000 acres — roughly 34 square miles or, as Michael Healey, chief public affairs officer for the Department of Environmental Management, noted about a third of the 61,000 acres the agency’s Division of Fish and Wildlife maintains in 24 wildlife management areas.

Of Rhode Island’s identified brownfields, 378 (14%) are in environmental justice areas and another 334 in these disenfranchised neighborhoods have been remediated, according to Ashley Blauvelt, an environmental engineer with DEM’s Site Remediation Program.

In the past two years, the Ocean State has added 115 brownfields — 59 in 2022 and 56 in 2021. Blauvelt said the discovery of these sites in Rhode Island is tied to the real estate market and the economy. For instance, in 2010, two years after the Great Recession of 2008, the state only added 30 brownfields to its inventory.

A property is typically identified as a potential brownfield when it’s going to be sold, refinanced or redeveloped — “basically, anytime there’s financing involved,” Blauvelt said. The property owner, buyer or bank will have the property’s soil tested for contaminants. If they are found to be above acceptable standards, DEM is contacted and the agency’s seven-person Site Remediation Program becomes involved.

“If they find something, anything above one of our standards, they have to report it,” said Blauvelt, a member of the Site Remediation Program team for the past 14 years. “That’s how the process kind of gets started. That triggers the need to do a site investigation and a further assessment of the property, depending on what the historical use might have been. I hate to call it this, but we’re a reactive program … the way our regs are written, we don’t go necessarily hunting for these sites.”

Redevelopment issues

Some of the brownfields remediated in the three states now host schools, affordable housing, senior centers, and assisted-living facilities. Their cleanup applauded by most everyone, but what is sometimes proposed for or built on top of these toxic grounds can generate concern, especially if the process excludes the local community.

In Rhode Island, for instance, the trend of building schools on contaminated sites in marginalized neighborhoods had to be curbed by a 2012 bill that prohibits the construction of schools on industrial waste sites where there is potential for toxic vapors to seep into classrooms.

Less than a year later, when development interests attempted to gut the law, Amelia Rose, the then-director of the Environmental Justice League of Rhode Island, which pushed hard for the 2012 legislation, noted at a Statehouse hearing that she supported the idea of reusing brownfields, but not at the possible expense of society’s most vulnerable.

“We value the reuse of brownfield sites. It doesn’t do anyone any good to leave them festering,” Rose testified. “But there are appropriate uses, like commercial, industrial uses that aren’t polluting and open space, which many inner-city neighborhoods are lacking. They would be excellent sites for solar panel arrays and wind farms. They’re not appropriate for schools, senior centers, and shelters.”

The decade-old law was drafted after schools, such as Alveraz High School, DelSesto Middle School, and Anthony Carnevale Elementary School, were built on contaminated sites in Providence.

The debate started in March 1999, when local residents saw bulldozers breaking ground on an overgrown but well-known former dump on Springfield Street. The site had been selected for the middle and elementary schools in 1998, but construction began before it was permitted, and with no communication to the surrounding community.

The Springfield Street landfill was unique because, while an estimated 300,000 tons of waste and fill material were dumped there before the site became overgrown, it was never a licensed facility. In 1999, the city, which had operated the site in the 1960s and ’70s, denied that it had been a dump at all.

Testing revealed the soil at the site was contaminated with heavy metals and VOCs — chemicals that easily escape the ground and enter the air we breathe. While soil capping can block heavy metals, VOCs are trickier. Buildings can have a “chimney effect,” pulling volatile substances out of the ground and into their interior air.

Concerned residents teamed up with Rhode Island Legal Services to file civil action lawsuits against the city and DEM. One suit charged “environmental racism,” because the prospective student body was predominantly non-white; another charged failure to give adequate notice of the planned construction and demanded that the schools not be opened due to potential hazards.

The schools opened in 1999. To counteract the potential health hazards, both schools include a foundation-level — or “sub-slab” — ventilation system and an air-monitoring system. The systems are inspected quarterly. This ventilation system works by a vacuum that sucks out potentially contaminated air at the foundation and routes it through a pipe to the roof, where it is released.

The vast majority (88%) of the students enrolled at Anthony Carnevale Elementary School are non-white, with Hispanic/Latino being the largest percentage of the student body. At DelSesto Middle School, 77% of the students are Hispanic/Latino and 10% are Black.

Jorge Alvarez High School, which opened in 2007, was built on the former site of the Gorham Manufacturing Co. As a result of the various jewelry manufacturing processes used at the Gorham factory for nearly a century, much of the land and water on the Adelaide Avenue site were significantly contaminated. Chemical solvents, such as trichloroethylene and perchloroethylene, that were used to clean metal and machine parts in the factory seeped into the land and created underground pools.

A sub-slab ventilation system was installed to vent out any potential soil gas vapors coming from contaminated groundwater. Indoor air quality of the school is tested every three months to ensure there is no contamination.

In the years leading up to the school’s construction and opening, the non-white percentage of the neighborhood’s population increased from 25.7% in 1990 to 59.5% in 2000 to 71.7% in 2010.

Championed for both economic return on investment and public benefits, brownfield redevelopment projects are not without their risks. The biggest risk is underestimating the size and scope of a cleanup.

Improperly assessing a remediation can reduce or eliminate the fiscal return on a project and/or overlook a future public health hazard. For example, regulatory changes in the identification and designation of contaminants of emerging concern, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Labeled as “forever chemicals,” PFAS are a family of fluorinated compounds that are both highly mobile and persistent in the environment. These compounds have only become a common focus of regulatory concern in the past six years.

An enduring legacy

The Industrial Revolution left many southern New England cities and towns with a lasting legacy: pollution that turned once-health land and water into toxic dumps.

In 1793, the opening of America’s first water-powered textile mill, on the Blackstone River in Pawtucket, marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. This manufacturing triumph also gave Narragansett Bay a jump-start over many of the nation’s other estuaries in serving as a receptacle for industrial waste.

By the early 1970s, the Audubon Society had labeled the Blackstone River “one of America’s most polluted rivers,” and the Woonasquatucket, Charles, and Housatonic rivers, among others in southern New England heavily used by manufacturers, had been profoundly altered by their industrial pasts.

By the end of the 1980s, thousands of brownfields pockmarked the southern New England landscape, especially in its core urban areas. Remediating brownfields is a constant battle that pits public health and environmental concerns against cost factors. Cleanup efforts are often interrupted by hidden obstacles, such as underground storage tanks filled with petroleum products, and finding the parties responsible so they can pay their share can be grueling.

This practice of contaminating the environment and then leaving behind scarred remains — after the offending business goes bankrupt, leaves for greener pastures, or ties up the matter in court knowing local and state entities often lack the funding and the gumption to fight — continues to this day.

These dilapidated properties, however, often represent do-overs, especially in a region lacking space.

“It’s not like we can expand our borders and become bigger,” DEM’s Healey said. “So we have to become smarter at reusing these contaminated sites, because in many cases they’re in really important blocks in areas of cities or towns, and they’re now in sort of a decrepit state.”

These infirm and toxic sites, however, are largely concentrated in economically distressed areas. Their remediation and reuse key to community revival, but too much brings gentrification and too little keeps neighborhoods disenfranchised.

During the past 28 years, southern New England has been the beneficiary of considerable EPA funding to help remediate brownfields. As of last July, the region had received $310,855,354 to assess and remediate brownfields — Rhode Island $51.5 million, Massachusetts $153 million, and Connecticut $107 million.

But transforming brownfields into community assets is no easy task. It takes money — plenty of it — patience, often a public-private partnership, and some creative thinking — such as encouraging/incentivizing ground-mounted solar projects on these polluted parcels.

Late last year, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont announced $24.6 million in state funding to help communities with the costs associated with assessing and remediating 41 blighted parcels in 16 municipalities. The grant and loan funding for this work came from the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development’s Brownfield Remediation and Development Program.

In Hartford, $3.5 million in state funding helped remediate the former Capewell Horse Nail Factory site into a mixed-use residential and commercial space known as the Capewell Lofts. Abandoned since early 1980s, the Popieluszko Court site had contained high levels of asbestos, lead, VOCs, and PCBs.

“We really enjoy this line of work. Being part of the effort to revitalize properties to get them back on the tax roll and to, obviously, clean them up is very rewarding,” said Raymond Frigon, assistant director of the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection’s Remediation Division, who has been with the agency for 32 years. “It’s been amazing to see renewed interest in these properties. We’ve had more applications to our brownfield programs in the last three-year period then I would venture to say than we’ve ever had. This is a good thing.”

In 1998, Massachusetts passed a law, the Brownfields Act, creating financial incentives and liability relief for parties that take on brownfield remediation projects. The law provides funding to administer programs targeted toward the cleanup and reuse of contaminated properties. In 2006, the state extended the Brownfields Tax Credit and made the credits transferable. The Legislature also periodically recapitalizes the Brownfields Redevelopment Fund.

David Foss, statewide brownfields coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, noted there is no standard outcome of brownfield redevelopment, but listed some examples of successful projects, including public park and open space, rail trail and bike paths, municipal facilities, senior centers, schools, medical and biotechnology offices, senior and affordable housing, mixed-use commercial and residential developments, and ground-mounted solar arrays.

He singled out the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) redevelopment project in North Adams, which saw a 16-acre industrial brownfield transformed into one of the largest contemporary art museums in the country. (There are currently nine brownfields listed in the western Massachusetts city.)

“It’s a beautiful success story that took a lot of stakeholders to say, ‘Hey, we want to make this investment in this community,’” Foss said. “Having that neighborhood outreach is really important.”

In 1995, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed the Industrial Property Remediation and Reuse Act. This law established legal liabilities for cleaning up contaminated sites and established the structure for liability relief for parties interested in cleaning up and redeveloping brownfields.

“Most of the sites that are reported to us are actually reported as a result of banks requiring due diligence,” DEM director Terrence Gray said. “If they find issues, they have to report those issues to us. And then the banks a lot of times want a resolution. It doesn’t have to be a full cleanup, but they want certainty as to what we’re going to require so they can sort of monetize that in whatever financing they’re developing for the property.”

The remediation of brownfields, however, typically involve taxpayer money. For example, last year Rhode Island voters approved, by an overwhelming 67%, a $50 million Green Bond that included $4 million in matching grants to clean up former industrial sites “so they may revitalize our neighborhoods, be returned to tax rolls, and create jobs.”

Rhode Island has so far invested more than $14 million for 62 projects in 15 municipalities through the Brownfields Remediation and Economic Development Fund. Half of that funding has helped remediate sites in environmental justice areas, according to state officials.

Among the brownfield projects that bond funding has helped redevelop include: the Westerly Education Center; the What Cheer Flower Farm; two Woonsocket middle schools; ground-mounted solar arrays; Community MusicWorks; and the Thames Street Landing in Bristol.

That $14 million, according to state officials, has leveraged nearly $950 million in other brownfield investments and cleaned up more than 200 contaminated acres. These projects have helped build new schools, businesses, affordable housing, and recreational space on formerly vacant properties throughout the state.

From locomotive and jewelry manufacturing to textiles and steel mills, southern New England has a long history of industrialization. While the region’s manufacturing industry gave rise to an economic boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, few operating mills remain today.

It was with a slight tip of the hat to those industries that made Providence economically successful that The Steel Yard was founded in 2002. Those who started the nonprofit artists collective also wanted to acknowledge the legacy of environmental degradation that heavy manufacturing has had on the city and state’s natural resources.

Two decades ago, The Steel Yard site was closed and in disrepair. For years, Providence Steel had sprayed its finished girders with lead-based paint, with the overspray leaving high concentrations of lead in the property’s soil.

The cost to transform this 3.5-acre brownfield on Sims Avenue into a community asset was substantial. The eight-year remediation project cost a few million dollars, and was completed thanks to federal and state grants, fundraising efforts, and donated materials and labor. Today, the old Providence Steel buildings have been converted into more than 9,000 square feet of workspace for artists and classrooms for education and job training in the industrial arts. The property has become a signature city attraction.

Birth of a brownfield

The Clean Air Act, the primary federal law intended to reduce and control air pollution nationwide, was initially enacted in 1963. It has been amended many times since.

The Clean Water Act is the main federal law governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters. The initial major law to address water pollution, called the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, was enacted in 1948. It took on its modern form when it was rewritten in 1972. Major changes, in 1977 and 1987, were made via amendments.

The Safe Drinking Water Act was passed by Congress in 1974, with amendments added in 1986 and 1996.

To keep future brownfield births down, these environmental laws and others, including those at the state and local level, need to be enforced in a non-selective manner. Taxpayers can no longer afford apathetic leadership and timid politicians that look the other way when irresponsible operations contaminate land and water for a better profit or because they just don’t care.

A 14-year-old scrap-metal operation at 434 and 444 Allens Ave. in Providence, a capped 6-acre hot spot along the city’s waterfront, perfectly illustrates how an environmental and public health hazard is created: years of timid enforcement, lack of political leadership, and an unneighborly business.

Rhode Island Recycled Metals (RIRM) opened illegally in 2009 without all of the necessary permits, including the one required to conduct car-crushing operations. It wasn’t until 2015 that the state took legal action against the company, and when it finally did, the business thumbed its nose at efforts to have fuel-leaking derelict vessels removed from the Providence River and keep its land-based operations from leaking contaminated runoff into upper Narragansett Bay.

To this day, 14 years after it began an unauthorized operation, RIRM has failed to face any significant punishment, as the business slowly and begrudgingly addresses several environmental violations and the matter remains stuck in litigation limbo. Since the original complaint was filed by DEM on March 4, 2015, more than 70 court hearings and conferences have been held. RIRM has been cited for disturbing the soil cap at the site with trucks and heavy machinery, for releasing pollutants from dismantled vehicles, and for inadequate runoff control systems and improper operations.

The scrap yard’s polluting operation was the impetus behind a 2016 petition, signed by 1,288 residents representing all 39 Rhode Island cities and towns, that Save The Bay delivered to then-Gov. Gina Raimondo. The petition read, in part: “Furthermore, as a taxpayer, I don’t want to pay the price of cleaning up pollution by others — pollution that could have been prevented with timely enforcement of environmental laws.”

The Allens Avenue site was contaminated during the 1980s by a computer and electronics shredding company that was allowed to conduct its operations on bare soil. The property has tested positive for toxins such as PCBs, a carcinogen commonly used in electronics. Some of the contaminated soil was removed and the site was capped.

The property sat unused until RIRM opened in 2009. The current and previous owners never received permits from the city or DEM to operate a scrap yard.

A lack of environmental enforcement from the beginning and fearful, uninterested, and possibly corrupted elected officials emboldened the business to ignore regulations designed to protect environmental and public health.

State officials and neighborhood residents now worry the 12-inch soil cover on the property has eroded, exposing the previously remediated site to Mother Nature and the public.

Nearly eight years ago, after an April 7, 2015 Superior Court hearing to get RIRM to clean up its property, it was suggested the company was low on cash and may not be in business much longer.

An attorney representing RIRM, told ecoRI News scrap-metal prices had dropped 70%, leaving the company “out of money.”

“It’s our understanding that their intent is to close the facility,” DEM’s chief of compliance and inspection said at the time.

Instead of the the city, DEM, and the Coastal Resources Management Council assertively enforcing laws from the start, officials were now hoping the low price of scrap metal would solve a problem the state had failed to adequately address.

When the business and its representatives were peddling the “we have no money” defense, there was legitimate concern that RIRM might just walk away without cleaning up its piles of scrap metal, vehicle parts, unidentified steel barrels, and large boats, one of which was still submerged.

“This site really is a mess,” Michael Rubin, assistant attorney general, said during that April 2015 court hearing.

Nearly eight years later, the illegitimate business continues to operate.

That is how a brownfield is born.

Note: The population demographics and poverty rates used in this story came from the U.S. Census Bureau. To read a story about Superfund sites in southern New England, click here.