Products for Body and House Aspire to Wean Us Off Toxins

November 28, 2022

Look around any big grocery store and notice the mountains of single-use plastic packages, cradling everything from cantaloupe cubes to baby wipes to squirt cheese.

If you are a biochemist looking at ingredient labels, you also will notice that skin-care products, household cleaners, and many other items may contain chemicals that can cause cancer, decreased fertility, hormonal and immune system disorders, and high cholesterol.

If the thought of all that plastic in the environment and toxins in our bodies sends your blood pressure soaring, you have a tool to fight back. It’s in your wallet.

Many companies across the country, including a few in Rhode Island, are manufacturing and selling products that eliminate harmful or toxic ingredients on the inside and plastic or non-degradable packaging on the outside.

The simple principle of use, refill, and reuse drives the strategy of many of these producers, which are selling toxin-free necessities such as body hygiene products, household cleaners, laundry soaps, and baby and pet products, largely through the internet and delivery services but sometimes through local retailers or resellers.

“Refill Is the New Recycle,” declares the website for Blueland, maker of many personal and household cleaners that it mails to customers in recyclable boxes packaged with paper tape and water-based inks.

(The refill-is-the-new-recycle declaration echoes a growing sentiment among plastic pollution experts in this country that recycling can never significantly stem the tide of throwaway plastics, partly because plastics come in many forms and contain many petrochemical additives that cannot be easily separated and reused.)

A common strategy is buying non-toxic products delivered in a recyclable container and then refilling it from the same producer, sometimes via a recurring subscription. Mailing boxes and envelopes for these goods are almost universally recyclable.

In order to reduce the weight of products during shipping, at least one company, Blueland, has engineered cleaning products, like dishwashing and laundry detergents, to remove the water, creating a compact dry tablet of chemicals to which the consumer just adds water.

Producers of toxin-free goods and eco-friendly packaging are not working in isolation. Many organizations offer technical guidance and certifications for excellent work. These include the biopreferred program and biobased certification of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Safer Choice, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) certification, the Plastic Pollution Coalition, Made Safe, Green America, and the Forest Stewardship Council, for one company’s bamboo toothbrushes.

Purity From Johnston

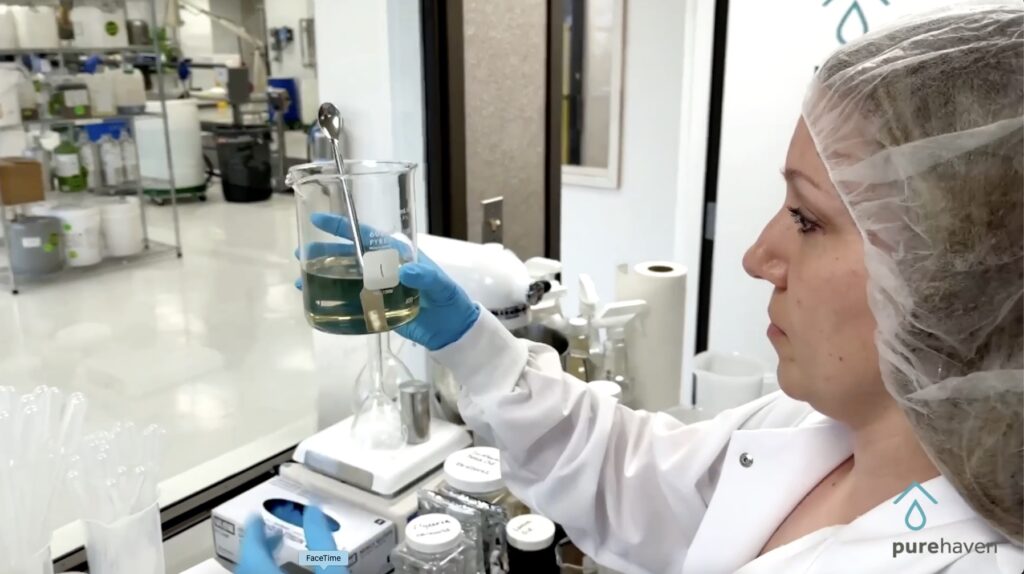

Pure Haven, a maker of skin-care products, household cleaners, and pet and baby products in Johnston, R.I., was founded in 2009 by Kim Anderson, after her teenage daughter learned some frightening facts about toxins in personal-care and cleaning products while doing a science fair project. (Ava Anderson Non-Toxic was eventually sold after some controversy arose.)

Miranda Inglis, Pure Haven’s CEO, said the company is a small-batch manufacturer that controls the integrity of every ingredient it uses, from sourcing and purchase through handling, heating, and mixing — all of which can change the chemical structure of ingredients — to bottling. The water in Pure Haven products is multi-filtered and treated with ultraviolet light and reverse osmosis. Equipment is cleaned carefully, as are bottles that go to consumers.

Common commercial products on grocery or pharmacy shelves may be laced with toxic chemicals and carcinogens partly because of a law dating to the days of the Great Depression. Inglis said the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 in effect exempted cosmetics from FDA oversight. She said about 80,000 different chemicals may be used in personal- and skin-care products and household cleaners. Of this number, 1,300 are banned in Europe; only 11 are banned in the United States.

Even people who diligently read ingredient labels on products cannot learn all of what is in them, Inglis said, because some elements — called “sub-ingredients” or “contaminants” — are a byproduct of the manufacturing process, and there is no requirement to name them. Also, product manufacturers are allowed, by law, not to name the ingredients in a “fragrance” or “parfum” because those are considered to be a trade secret.

Inglis said categories of ingredients that are never used in Pure Haven products include parabens, endocrine disruptors (which mimic hormones), petroleum-based chemicals, silicones, dyes, sulfates, formaldehyde, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, commonly known as PFAS and sometimes called “forever chemicals,” which are suspected of a wide range of threats to human health.

(In addition to entering the blood stream and brain through the skin, these forever chemicals will inevitably be washed off and go into wastewater systems and waterways, according Inglis.)

Conversely, Pure Haven products use ingredients that are almost all recognizable and pronounceable: shea butter, coconut oil, baking soda, aloe vera juice, chia seed extract, witch hazel, and extracts of orange peel, cucumber and aspen bark, to name a few.

“You can make a very good product that works without [toxic] ingredients,” said Inglis, adding that the cosmetics and skin-care industry “is mostly self-regulated. And big [manufacturers] want to be able to keep their costs down.”

The implicit message that Pure Haven conveys to its customers, Inglis said, is “you shouldn’t have to worry about this. We are going to control all the variables we can to make sure you are getting a safe product.”

She noted safe alternatives to commercial personal-care and household products are not cheap, because the availability of materials to make non-toxic goods is not in step with the need. Only when scientists and laboratories ramp up production of alternative ingredients will they be widely available to manufacturers. Also in the case of Pure Haven, goods are made in small batches, which requires more handling and staffing through the manufacturing process.

Add Water, Start Cleaning

Blueland, with employees and factories scattered throughout the country, was co-founded in 2019 by Sarah Paiji Yoo and John Mascari, who are now, respectively, CEO and COO of the company. As is often the case with origin stories of these companies, a woman was alarmed about the health impacts of mainstream products on her family and started thinking about alternatives. Yoo said her “aha” moment happened when she was looking into formula for her first baby, and she discovered the danger of microplastics in drinking water.

Yoo and Mascari’s important breakthrough was the idea of condensing the chemicals in hand soap or laundry soap, for example, down to a compact powder tab, with the consumers adding water at home. The huge benefit was to remove water and lighten the product, thus slashing shipping costs. An initial shipment of hand soap, laundry and dishwasher detergent, or household cleaner from Blueland includes tabs of condensed chemicals along with a glass bottle for soap, tin box for detergents, and a plastic spray bottle for cleaners. Refills of tabs come in paper envelopes.

Commercial “pods” of laundry detergent or dishwasher detergent are often wrapped in a thin layer of plastic called polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, also identified as PVOH). Experts disagree about the degree of danger, if any, to the environment from PVA in laundry or dishwasher detergent pods; some claim PVA goes straight into water treatment systems and waterways, where it breaks down into microplastics.

Blueland, working with the Plastic Pollution Coalition, has initiated a petition drive asking the EPA to regulate the use of PVA in packaged goods such as laundry pods. “The plastic film doesn’t readily biodegrade and over 75% of intact plastic PVA particle end up in our oceans, rivers, canals and soil,” according to Blueland. “The plastic has the potential to absorb dangerous chemicals and then make its way back up our food chain.”

The petition asks the EPA to do extensive health and environmental tests of PVA and remove it from the Safer Choice List, a centralized source of ingredients that are safer for human and environmental health.

The company is equally serious about the purity of ingredients. “Every ingredient is evaluated down to the molecular level,” Yoo said. “We have a robust certification of chemicals” along with approvals and certifications by entities like the Safer Choice program and Made Safe.

Yoo said Blueland has a million customers and has sold more than 10 million products. Its growth was propelled in part by appearances on the TV shows “Shark Tank” and the “Today Show,” along with write-ups in The New York Times and Vogue and word of mouth on social media.

Also, Yoo said, consumers are motivated. “It is exciting to see how many consumers have good intentions and want to make good choices,” she said, adding that products like Blueland’s also must be effective and easy to use.

When people hear about adding water to a tab of cleaning chemicals, they respond, she said, “This makes so much sense; why haven’t we been doing this before?”

Carcinogens in the Laundry

In 2006, Kate Jakubas, who later founded Meliora Cleaning Products, was a toxicologist working on a project to remove lead from the brass alloy that was used to make faucets. She became interested in the idea of removing toxins from common products, so she enrolled at Illinois Institute of Technology to study environmental engineering.

Near the time of her graduation in 2013, Jakubas read about a campaign by Women’s Voices for the Earth that eventually succeeded, she said, in forcing Proctor & Gamble to remove a carcinogen, 1,4-dioxane, from a laundry detergent. She took a business class and wrote a plan for a new business that would create a toxin-free laundry detergent.

The business soon became Meliora Cleaning Products, launching with a laundry powder. Jakubas, now COO, acquired a partner, Mike Mayer, now company president, and began manufacturing the laundry powder, followed by cleaning products and bath and body soaps. They got into stores by knocking on doors of retailers — like Mom’s Organic Market, an East Coast chain — and asking for shelf space. They attended farmers markets as a way to talk to consumers and learn what products they wanted.

Jakubas said Meliora’s marketing targets “the greenest of green consumers” but added, “We don’t believe that safe cleaning should be out of reach of any people.”

Meliora vets the environmental impact of its suppliers and always tries to source ingredients from the local economy. Jakubas said Meliora employs 13 people at its factory in Chicago and its products are sold in 300 stores. Its annual sales are between $1 million and $10 million.

Meliora markets its environmentally friendly products as a matter of self-interest for consumers. “We find that most people care about the health of themselves, their kids, their pets,” according to the company.

Meliora partners with Made Safe, which certifies the integrity of ingredients in products, and it is a certified B Corp, a designation for companies that meet high standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency.

Dishwashing Experts

Re:Dish, a company founded in 2020 in New York City, aims its considerable entrepreneurial and management firepower at a slightly different problem: single-use plastic food containers that, not surprisingly, are helping to inject tons of plastic into landfills and waterways.

Alison Rogers Cove, founder and CEO of Cambridge, Mass.-based Usefull, also envisions a circular foodware solution that would spell the end of disposable takeout products, most of which are not recyclable and wind up in a landfill or as litter.

Re:Dish is modeled on a laundry pickup and delivery service. Re:Dish provides sturdy, covered, plastic food containers to, say, the cafeteria or food service of large schools, companies, or institutions. The cafeteria fills the containers and serves the food. Diners then deposit the soiled containers in a Re:Dish-branded bin that goes back to the company for cleaning and immediate return to the customer.

Caroline Vanderlip founded Re:Dish after she spent a few years noticing the growing piles of trash in public places around in her home in New York. Those piles would have included some of the 1 trillion items of food-service packaging per year that are used once and thrown away in the United States.

Customers for Re:Dish are located from Westchester County to mid-New Jersey, and they include seven schools, law firms, a media company, and a big tech company. A single Re:Dish food container is used hundreds of times before it is ground into plastic scrap and reused for a new purpose. Vanderlip, the company’s CEO, said the company has tried to gamify lunch hour for diners by putting a QR code on each container. People can scan the code and see a history of how many times it has been used.

The QR code is a bit of fun, but with a deeper purpose. Vanderlip hopes employees of a firm using Re:Dish will get used to returning the containers to a branded bin and hopefully apply the principle of reuse in their own lives.

“We want to inculcate into [customers’] populations the whole idea of reusability,” Vanderlip said.

Re:Dish is serious about its own environmental footprint. It began auditing and measuring its own waste stream in 2021 and says its total waste diversion rate is 76%. That includes 2,400 pounds of food scrap sent to composting facilities, and a directive to its container supplier to stop wrapping plastic film around new products.

Re:Dish washing equipment is some of the most energy-efficient machinery on the market; it recirculates water from the final rinse and uses it again for the first rinse. There is a plan in the works to purify and reuse all water used for washing. Electric delivery vehicles are on order.

Re:Dish is big on gathering metrics of energy expended and waste deferred. This plays well into the needs of some corporate clients.

Many companies of all kinds are working to burnish their reputation in the eyes of customers, investors, and shareholders by adopting environmentally friendly practices. They are keenly aware of their ESG (environmental, social, and governance) profile as they craft and maintain a virtuous public image.

RE:Dish’s proprietary dashboard, called DishTrack, allows customers to manage their reusable container inventory and also to know their environmental impact from moment to moment. DishTrack provides metrics like carbon and water reduction that can feed directly into its customers’ emissions reporting and help customers meet their ESG goals.

“Corporations want to measure and publicize their environmental friendliness,” Vanderlip said. “Lenders, for example, are using a company’s ESG metrics as one way to evaluate a company’s future.”

Tapping into the reuse and sustainability methods of Re:Dish can be a boon for companies that are working on net zero goals or those that have made promises about pro-environmental actions and policies. “And now they have to figure out how to do it,” Vanderlip added.

According to the website Investopia, “(ESG) investing refers to a set of standards for a company’s behavior used by socially conscious investors to screen potential investments. Environmental criteria consider how a company safeguards the environment, including corporate policies addressing climate change, for example.”

Reselling, Refilling

Dana Lane, founder of The Matter Shoppe, based in Providence, was fairly new to Rhode Island in 2016 when she got a mailing from the state that promoted composting, and, later, a flyer describing the ways people were mismanaging their recycling. She learned the state has a single central landfill, and she was taken aback by what looked to her like a meager effort to stave off a trash apocalypse.

Around the same time, she took a hard look at her own trash and found lots of bottles for personal-care items, including supposedly eco-friendly products wrapped in plastic.

Lane decided to create a business as a “reseller,” buying eco-friendly products like shampoo and laundry detergent at wholesale prices and them reselling them at a markup through her website.

She came up with her first $4,000 for the business by collecting and returning bottles and cans in Massachusetts, which has a bottle deposit and return program, and another $4,000 through crowd funding. She bought a van (a former U.S. mail truck) and in 2022 she began cruising places that welcomed her and like-minded consumers, like farmers markets and a vegetarian restaurant.

Looking to the future, Lane hopes to use the van as a “refillery,” where customers can bring empty containers to refill or to buy a product in its own container, with the idea of refilling it in the future. Plans also include acquiring more vans, hopefully operated by solar power.

Lane defends her business model against critics who question the environmental impact of transporting the goods, and those who complain about the often-higher prices for green products.

She said her company uses only the U.S. Postal Service, so it does not put additional trucks on the roads.

As to the higher cost of sustainable products, Lane offers a multitude of reasons: ethical labor practices bring higher costs; high-quality reusable materials cost more than disposable materials; current low demand for sustainable products requires vendors to invest more in new technology, packaging, and equipment; and many vendors are artisanal small businesses that cannot buy supplies in large volumes.

Ana Duque runs a similar business in Pawtucket called Green Tenderfoot, a zero-waste company she started in 2019 that allows customers to buy products that lower their waste footprints, such as metal straws, mesh grocery bags, and reusable feminine products. The business also features personal-care refilling stations.

Lane believes producers and business owners bear the responsibility to make people aware that eco-friendly products are a good and accessible way to buy necessities and fight pollution. “Spreading awareness starts with business owners and people who sell the products,” she said. “We have to shift the ways we package and sell things.”

Great article. I didn’t know about PVAs – I’ve used Dropps for years now and had no idea the film could be problematic. I decided to make the switch to Blueland for my household cleaning products!

Thank you for sharing this information. I especially enjoyed learning about local companies and appreciated the fact that you included links.