Melting Arctic Sea Ice Not Just a ‘Far Away’ Problem

October 21, 2022

NARRAGANSETT, R.I. — The Arctic Ocean may be nearly 1,700 miles north of Rhode Island, but melting sea ice there affects the climate here.

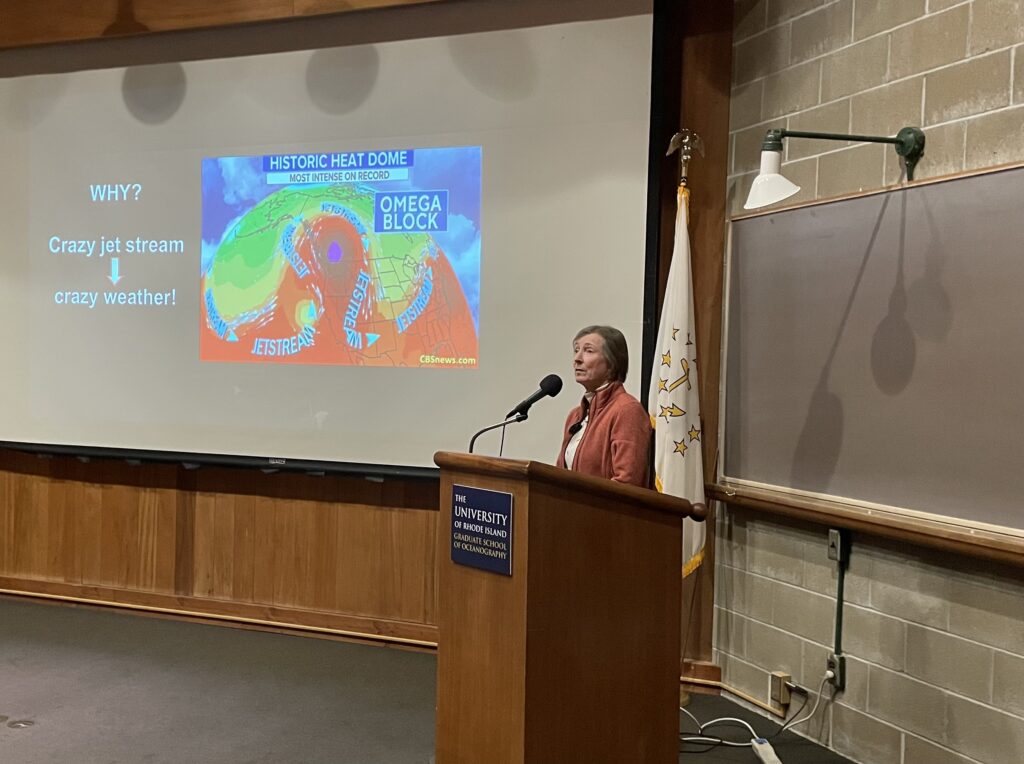

Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, formerly the Woods Hole Research Center, told the audience at the Oct. 19 Charles and Marie Fish lecture at the University of Rhode Island’s School of Oceanography that the impacts of melting Arctic sea ice include sea-level rise and extreme weather events.

And those impacts aren’t happening sometime in the distant future. Francis made it clear that climate-change effects, such as changes in the patterns of the jet stream and the polar vortex, are being observed now and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is urgent.

The jet stream is an air current that moves around the Earth a few miles above the surface. Pointing to a map showing curves and loops in the jet stream rather than a single band of air flowing from the west, Francis said those changes in the flow cause extreme weather.

“What you see is that it’s taking this very loopy pattern, dipping way up toward Alaska and the jet stream separates the cold air to the north from the warm air to the south, so whenever we get one of these great, swooping northward bulges in the jet stream like that, it’s allowing all this warm air to get pumped up from the tropics, way up into British Columbia,” she said.

When the jet stream dips southward, cold air moves in.

“The jet stream is responsible for just about all the weather that we experience around here,” Francis said.

Another major contributor to our weather is the polar vortex, areas of low pressure and cold air, much higher in the atmosphere than the jet stream, that surround both the North and South poles and strengthen in winter.

When the polar vortex is disrupted, cold air moves south.

“When we get one of these disruptions, it also tends to reinforce the waves that are in the jet stream, making them even bigger, and when we have big waves like this in the jet stream, they tend to stay where they are for a long time, and so the weather that they create also tends to stick around for a long time,” she said.

Here’s where the changes in the Arctic climate come in: Researchers have determined that disruptions to the polar vortex, during which cold air leaves the Arctic, are occurring more often.

“All of that cold air has left the Arctic and it’s gone down over the continent,” Francis said.

Temperature records show that the Arctic is warming faster than any other place on Earth.

“The most recent estimates are about four times faster than the globe as a whole, and this is a very big deal,” Francis said.

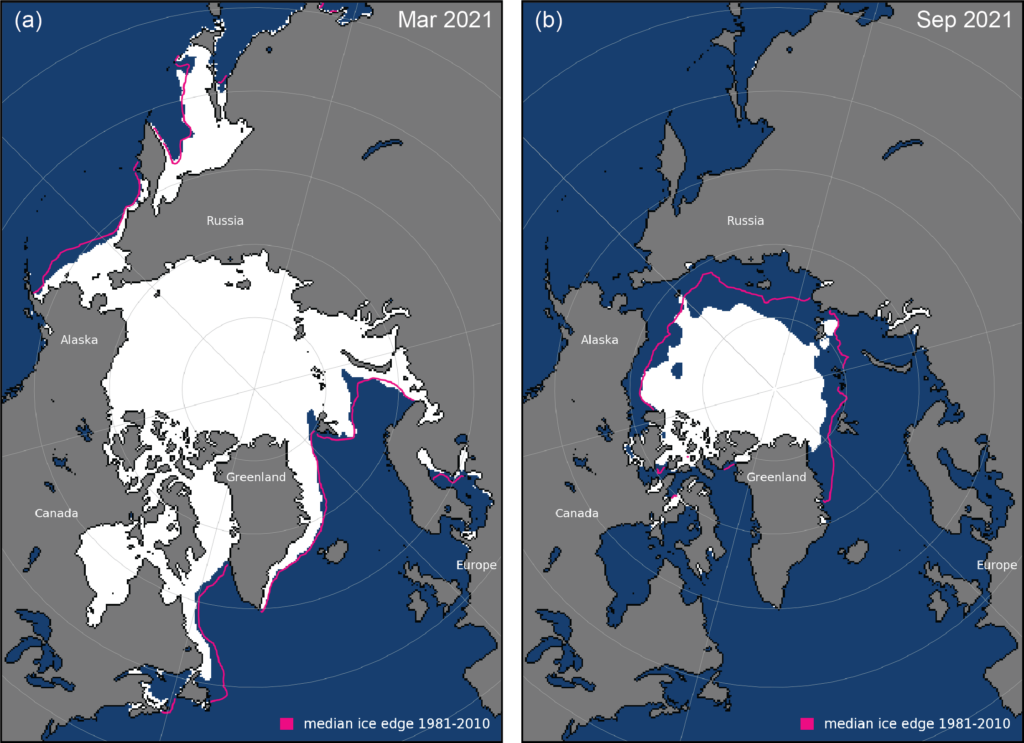

As the Arctic warms, the sea ice melts, and the loss of the white ice, which reflects the sun, and the increase in dark, open water that absorbs the sun, cause the ice to melt even faster.

“Comparing what it was back in the early ‘80s, we’re losing all of those thick ice types,” Francis said. “Basically, all of the thick ice has disappeared and this is only a 40-year period. Not only are we losing the ice thickness, we’re losing the ice area.”

As the sea ice disappears, Arctic permafrost, frozen soil, is also thawing, and as it thaws, it releases greenhouse gases.

“As that permafrost thaws, the microbes in the soil start digesting all of that organic matter and what comes out? Carbon dioxide and methane, adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere,” Francis said. “So, this is a potentially huge what we call a positive feedback or a vicious cycle that’s beginning to happen up in the high Arctic.”

Francis said the connection between the atmosphere and the ocean, which is currently experiencing its own heat waves, one off the Pacific coast of North America and another of the East coast, extending north all the way to Greenland.

“These marine heat waves tend to favor those northward bulges in the jet stream, not always, but they tend to favor that configuration,” Francis said. “I think, in this case, it’s certainly playing a role in the pattern that we have right now. … The ocean and the atmosphere are intimately connected and we’re trying hard to unravel some of these relationships that are unfolding as the climate evolves. … We think that there’s an interaction between a marine heat wave in the south and the heat that’s coming out of the Arctic Ocean as the sea ice starts to form in the fall.”

Francis described conditions in the future, which will be improved or catastrophic, depending on how humans address the climate crisis.

“There are different options, and of course, both options depend on us,” she said. “No matter what we do today, we’re in for a lot more warming, a lot more climate change, a lot more extreme weather, a lot more sea-level rise. But, if we can start now, we can avert the worst.”

On the other hand, Francis warned that doing nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will result in a total loss of summer sea ice in the Arctic Ocean by 2050.

“If we keep emitting greenhouse gases like there’s no tomorrow, we’re going to see a summer very soon when there’ll be no sea ice left at all in the Arctic Ocean,” she said. “And we’re very confident that it’s probably going to happen sometime, certainly before 2050. It could happen any summer now, actually.”