Legal Filings Question Champlin’s Marina Agreement

February 22, 2021

The legal saga continues over the controversial expansion of Champlin’s Marina & Resort on Block Island. The project slated for Great Salt Pond threatens an environmentally sensitive tidal lagoon under pressure from summer boaters in need of dock space in the crowded 800-acre body of water.

In response to the the surprising mediated agreement reached Dec. 29 between the marina’s owner and the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) board, the attorney for the project’s opponents recently filed several documents in Rhode Island Supreme Court — all targeting the state coastal zoning agency.

In the Feb. 16 filings, R. Daniel Prentiss called the mediated agreement “a backroom arrangement.” The CRMC board, he said, “engaged in blatantly illegal procedure” with no authority to settle ongoing litigation without the town of New Shoreham and other intervenors, which include the Block Island Conservancy, the Block Island Land Trust, the Committee for the Great Salt Pond, and the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

A Jan. 8 joint motion filed by CRMC and Champlin’s Realty Associates Inc. asking the Supreme Court to consummate the memorandum of understanding (MOU) is “astonishing for its brazen illegality and amateurish execution,” Prentiss wrote in opposition to the motion. “Its repellent, deeply corrupt effort to effect an inside, secretly contrived fix of contested litigation is a naked affront to the rule of law and to the dignity of this court, whose jurisdiction over the matter is exclusive.”

CRMC declined to comment on the latest proceedings. But Champlin’s attorney Robert D. Goldberg contends that the town of New Shoreham and other intervenors are non-party intervenors and therefore can’t determine the outcome of the litigation.

“Champlin’s and CRMC entered into mediation in good faith to settle a 17-year-old dispute,” Goldberg’s spokesperson, Dyana Koelsch, told ecoRI News.

The legal fight between CRMC, Champlin’s Marina, the town of New Shoreham, and environmental groups began in 2003, when a proposal to nearly double the marina’s size was announced. CRMC denied the application in 2006. Champlin’s appealed to Superior Court, where the decision was reversed. Opponents appealed to Supreme Court, which asked Superior Court and CRMC to review the decision. In 2013, CRMC denied the expansion again. Champlin’s appealed. Last February the Supreme Court upheld CRMC’s decision.

Champlin’s appealed last July. According the Hummel Report, the mediation process went forward with retired Supreme Court Chief Justice Frank J. Williams at the behest of CRMC. A deal was brokered between CRMC and Champlin’s in late December for a 1.5-acre buildout without participation by the town and other intervenors. The mediation was held in executive session and the meeting minutes are sealed.

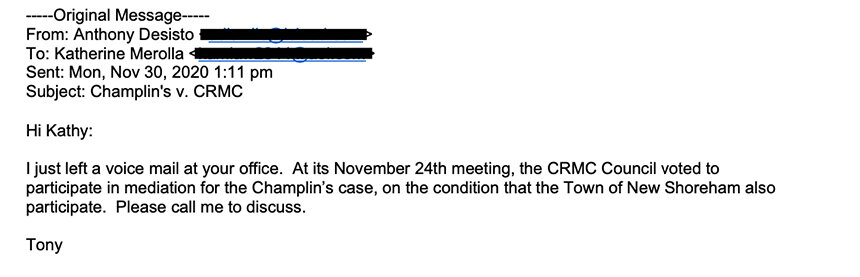

The opposition was shocked to learn that mediation went forward after the town was told it wouldn’t occur without New Shoreham representation. Prentiss cited a Nov. 30, 2020 email from CRMC’s attorney stating that the agency would only join the mediation if the town participated. CRMC’s attorney, Anthony DeSisto, later told the Hummel Report that the comment was a “misstatement.”

Goldberg noted that Prentiss and the New Shoreham Town Council made the decision not to accept an invitation to join the mediation in a nonpublic executive session.

“Disappointingly, and without any discussion with the mediator or the parties to the lawsuit, the town and its attorney, who also represents the other intervenors, decided in a closed-door meeting not to participate in the mediation,” Koelsch said.

The Feb. 16 court filings detail other aspects of the case. CLF was granted intervenor status by the court in 2004. The environmental legal group with its own team of lawyers filed a memorandum Feb. 17 stating its opposition to the mediated CRMC-Champlin’s agreement, noting that both parties were incorrect to say that CLF had been notified of the invitation to mediate because Prentiss had been notified.

“CLF is not now and never has been represented in this matter by Attorney Daniel Prentiss,” CLF attorney James Crowley wrote. “Regardless of any communication the CRMC did or did not have with Mr. Prentiss regarding mediation, CLF was not in any way notified of, or invited to participate in, the mediation that resulted in the MOU between Champlin’s and the CRMC.”

Champlin’s has 10 days from the recent filing to respond to the request for oral arguments or ask for more time. No timeline has been set for proceedings.

News about the MOU rankled Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha, prompting him on Feb. 8 to ask the court to intervene in opposition to the CRMC-Champlin’s agreement. Neronha contends that CRMC didn’t have jurisdiction in the case and failed to comply with the court-mandated process.

Champlin’s objected to the attorney general’s request to intervene on Feb. 9, saying that the case has been settled. It noted that state agencies like CRMC have jurisdiction over environmental actions, not the attorney general.

Goldberg cited a 2008 Supreme Court decision that will likely be relied on to argue that the CRMC-Champlin’s agreement is valid. In that case, the town of Richmond, an intervenor, was denied its objection to a settlement agreement between the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) and a textile mill that polluted soil and groundwater.

The judge criticized DEM for “ham-handed treatment” toward the town by giving it a draft of the settlement on the day it was signed. But the judge ultimately ruled that DEM had the authority, as a state agency empowered by the General Assembly, to make the agreement.

The CRMC-Champlin’s case and the subsequent spotlight on CRMC’s deficiencies prompted Senate leadership to table the recent fast-tracking of CRMC reappointments made by Gov. Gina Raimondo. The reappointments of CRMC board chair Jennifer Cervenka, vice chair Raymond Coia, and member Donald Gomez were paused the morning of Feb. 10, the same day their confirmation hearings were scheduled before the full Senate. As of Feb. 19, the three appointments “remain on the desk,” according to Senate spokesperson Greg Pare.

The reappointments of two other CRMC board members, Joy Montanaro and Jerry Sahagian, were pulled before the Feb. 3 Senate committee hearing that ultimately advanced Cervenka, Coia, and Gomez to the full Senate.

Meanwhile, Save The Bay issued its support for Neronha’s request to intervene, noting the ecological risks of the project. The environmental group has long criticized the CRMC board over its review and approval process for coastal development. In this case, the agency failed to adhere to the Administrative Procedures Act, according to Save The Bay.

“The MOU was filed without findings demonstrating that environmental impacts to public trust resources were carefully evaluated — findings relating to competing public trust uses, harbor safety, water quality, erosion and impacts to diversity of plant and animal life,” said Kendra Beaver, staff attorney for Save The Bay, in a recent press release. “The attempted settlement circumvented the public process mandated by law, reversed earlier decisions, excluded parties and the public, and creates a dangerous precedent.”

The marina was sold Dec. 23, 2020, less than a week before the mediation agreement was signed. Champlin’s Realty Associates Limited Partnership’s general partner, Champlin’s Realty Associates, Inc., sold the marina and adjacent properties for $25 million to Great Salt Pond Marina Property LLC, a unit of Cranston-based Procaccianti Companies.

The real-estate investment and development company told ecoRI News that it isn’t part of the litigation, which was started by the previous owner, Joseph Grillo.

“[Procaccianti’s] full attention is directed towards addressing the many deferred maintenance issues that exist at the property,” Champlin’s Marina & Resort spokesperson Annie Mulholland said. “The design team is currently putting the final touches on a comprehensive property improvement plan which will include full renovations of the guest rooms and public spaces, as well as significant improvements to the marina infrastructure.”

Those changes, Koelsch said, are “significantly scaled back” from the 2003 plan and will not allow for an increase in its current boat count of 250. It also puts in place explicit rules for boats that will be docked there and rules for the entire marina, she noted.

“We believe the agreement as outlined in the MOU not only protects the environment of the Great Salt Pond,” Koeslch said, “it also allows for use and enjoyment by Rhode Islanders who otherwise might not have had access.”

When asked about the environmental protections, Koelsch referred to the CRMC-Champlin’s agreement outlining a reduced seaward expansion of the docks, limits on mooring uses, mandatory in-slip pump outs, and lighting requirements.

The controversial MOU implies that getting bigger and offering more parking increases public access, because “marinas are a principal means by which the boating public gains access to the tidal waters, and thereby provide an important public service.”

So, if you have the money to appeal, appeal, appeal, you can pretty much have your way. This is especially disappointing when our environment seems on the verge of collapse in part due to over-development. These boating tourists who demand to be accommodated seem to have forgotten what drew them to BI in the first place. I’m assuming it was its quaint beauty, but now I suspect it’s just the desire to be "seen."