Community Effort Makes Barrington More Climate Resilient

February 22, 2020

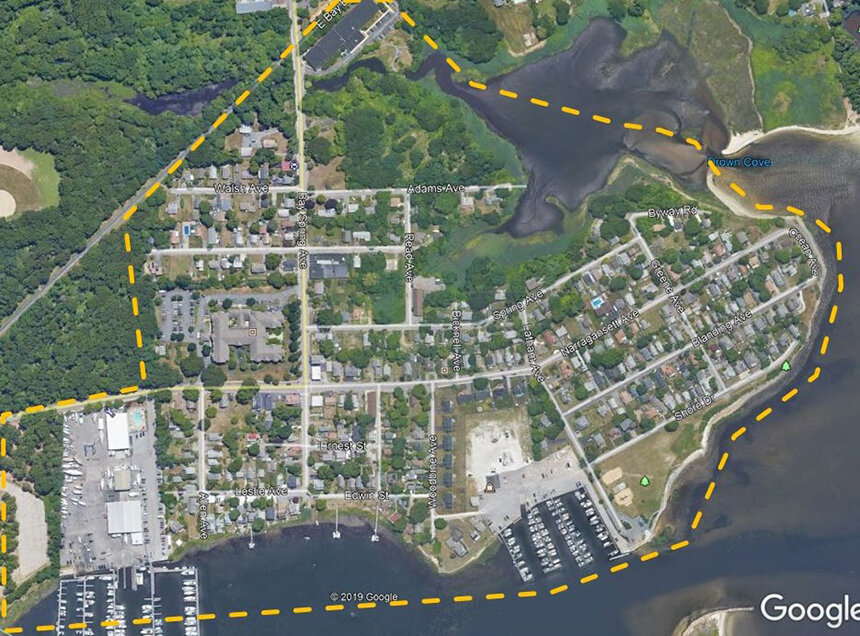

BARRINGTON, R.I. — The town, one of the lowest-lying communities in the Ocean State, occupies two peninsulas bound by Narragansett Bay to the west and the Palmer and Warren rivers to the east. The Barrington River separates the peninsulas. Unsurprisingly, sea-level rise, storm surge, and a crumbling shoreline pose serious threats.

The densely populated Bay Spring neighborhood, which juts out to where the Providence River meets Narragansett Bay, is one of the town’s most at-risk areas. Increased flooding and severe shoreline erosion have given the neighborhood a firsthand look at what the climate crisis looks like.

If the neighborhood’s climate challenges are ignored, marsh migration will eventually impact homes along Allin’s Cove and in other susceptible areas.

Town and state officials began addressing the visible climate impacts on the Bay Spring neighborhood and Latham Park about a decade ago. Repairs to the existing stone revetment protecting the northerly portion of Latham Park were completed in 2014.

Two years ago, a $234,000 grant from the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) helped fund the installation of a new playground and pedestrian walkways, the creation of rain gardens, and the planting of natural buffers at the popular waterfront park. The project also included the addition of more parking.

More recently, as part of an ongoing community-level effort, local officials, residents, and other stakeholders began a process to create a resilience plan for the neighborhood. The project’s goal is to build awareness about the climate crisis and identify specific actions that can be implemented to increase local resilience, according to Arnold Robinson, regional director of planning for Fuss & O’Neill, who is working with the town on the project.

A neighborhood tour was held Feb. 8 to identify areas of concern, and a brainstorming workshop was held Feb. 12 to share ideas. A workshop is scheduled for Feb. 26 from 7-9 p.m. at the Bay Spring Community Center, 170 Narragansett Ave., to prioritize potential actions and projects.

Robinson said the best community plans are those driven by the participation of residents, property owners, businesses, and civic organizations. With plenty of homes, two senior-housing facilities, and two marinas, he said the neighborhood is a “good place to apply real solutions,” such as allowing parts of Latham Park to flood and then drain naturally.

Among the other ideas that have been discussed include: building an oyster reef off Latham Park to slow erosion; salt marsh regrowth; better managing stormwater runoff; protecting western shore beaches with natural and hybrid infrastructure; and Read Avenue property buyouts and/or infrastructure removal.

Phil Hervey, the town’s director of planning, building and resiliency, said Read Avenue “is getting shredded” from frequent flooding, even during high tides.

Robinson and Hervey, both Barrington residents, noted that an important aspect of the project is not to impose solutions on residents.

“People living in the neighborhood have the best ideas because they live with the issues every day,” Robinson said. “They see solutions to the problems and challenges.”

A final report will be submitted to the town once all community input has been gathered, according to Robinson. He said the report would essentially be a shopping list of projects to make the neighborhood more climate resilient.

With nearly 20 miles of coastline, the Bay Spring neighborhood isn’t the only section of Barrington exposed to the impacts of a changing climate. The town is among the Rhode Island communities most at risk of flood damage from a hurricane.

Two roads — Wampanoag Trail and County Road — are among the most vulnerable in the state to sea-level rise. New Meadow, the lowest-lying land in town, is already prone to severe flooding. Mathewson Road and the houses that line it are threatened by storm surge.

Walker Farm, an old pig farm along Hundred Acre Cove and the Barrington River that has been town-owned property since the 1970s, like Allin’s Cove in the Bay Spring neighborhood, is suffering from erosion.

To address this problem, the town is allowing a low-level area about the size of a football field in the middle of the property to revert back to a salt marsh. With funding help from DEM, the town is also removing concrete long ago dumped along Walker Farm’s shoreline. Its removal, along with the creation of a 50-foot natural buffer, will help reshape the shoreline with vegetation that will make the area more resilient to storms.