Ocean State Grapples with How and Why of Beach Closures

April 13, 2019

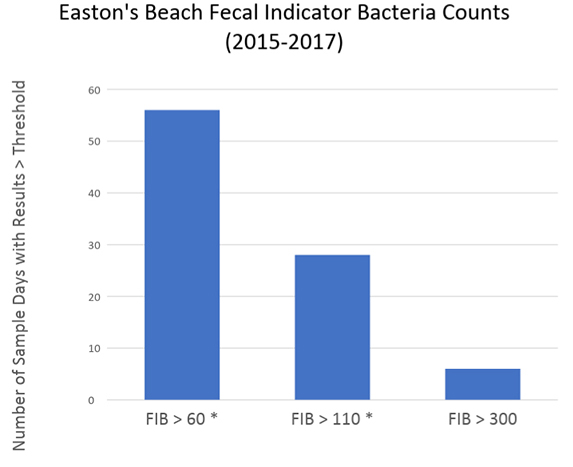

NEWPORT, R.I. — Nearly 100 times between 2015 and 2017, or about once every three days, water sampled at Easton’s Beach tested high for fecal matter. The popular beach, however, was only closed on four separate occasions for a total of six days.

The Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH), with help from Middletown-based Clean Ocean Access (COA), samples water at 70 marine beaches during the summer season — Memorial Day through Labor Day. The samples are analyzed to estimate the counts of enterococci, found in human and animal waste.

The Rhode Island standard for enterococci is a maximum of 60 colony-forming units (cfu) per 100 milliliters in both fresh and saltwater beaches. Anything above that is considered unsafe for recreational use.

From 2015-2017, Easton’s Beach water samples tested above 60 cfu 55 times, above 110 cfu 28 times, and above 300 cfu five times, according to DOH and COA data.

The fact Easton’s Beach was closed only four times — all in 2015, on Sept. 1-4, July 8-9, June 18-19, and June 16-17 — despite 88 samples testing above 60 cfu doesn’t speak to carelessness or some public-health coverup. By the time samples are collected and tested, some 48 hours have passed and tides have come and gone, leaving decisions to close beaches based on professional judgement. It’s an imperfect system that also feels political pressure to keep tourist destinations open.

The Ocean State has some 400 miles of coastline, with some of its beaches seeing up to 10,000 visitors in a single day during the summer.

“Under the current system, decisions are made two days late,” said Sherry Poucher, DOH’s beach program coordinator. “Sometimes we get the prediction right and sometimes we don’t. We don’t want to falsely close a beach, and we don’t want to threaten public health by keeping a beach open.”

To better protect both public health and the state’s economy, DOH and COA partnered on a recently completed project funded by a $16,000 grant from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “Research Needs for Marine Beaches” used an EPA software program that predicts beach water quality to improve management at high-concern beaches, such as Easton’s Beach and Oakland Beach in Warwick.

DOH’s Poucher and Jillian Chopy, a research assistant, and COA project manger Eva Touhey and research assistant Sabrina Pereira plugged some 50 variables, including rainfall, wind direction and speed, tide data, and air and water temperatures, into the modeling program. They presented the project’s results April 9 at the Newport Public Library.

Their efforts focused on Easton’s Beach and Oakland Beach — beaches with historical trends of increased bacteria levels — for the years 2015-2017. They sifted through data from various state and federal agencies to get the necessary variable information. It was a time-consuming task that took four months.

The modeling predictions for the two popular beaches that the EPA software created are going to be used to advance the state’s understanding of bacteria levels at high-use beaches, improve public health, and provide a model for studying future locations along Rhode Island’s coastline. The data is expected to help create a management approach that better understands the how and why of water-quality problems at local beaches.

Water-quality conditions for recreational use, such as swimming and boating, are a public-health indicator focused on the risks of fecal pathogen contamination. Fecal coliforms, escherichia coli, and enterococci are considered primary indicators for the presence of human pathogens in water.

For instance, on June 7 2006, after heavy rains, Atlantic Beach in Middletown and Easton’s Beach were closed after both were found to have 24,192 cfu per 100 milliliters. The beaches remained closed for four days.

Exposure to harmful microorganisms through swimming and boating can cause health problems such as gastroenteritis and sore throats, or even meningitis and encephalitis. Fecal pathogens are the leading cause of water-quality impairment in the country.

The stream that runs into Easton’s Beach, from a moat across Memorial Boulevard, is a primary source of enterococci contaminating one of Rhode Island’s signature beaches.

The $6 million Easton Beach UV Stormwater Disinfection System treats polluted runoff before it’s released into Easton’s Stream. The ultraviolet system of lights began operating in May 2011 and has reduced the number of days Easton’s Beach and Atlantic Beach have been closed to swimming.

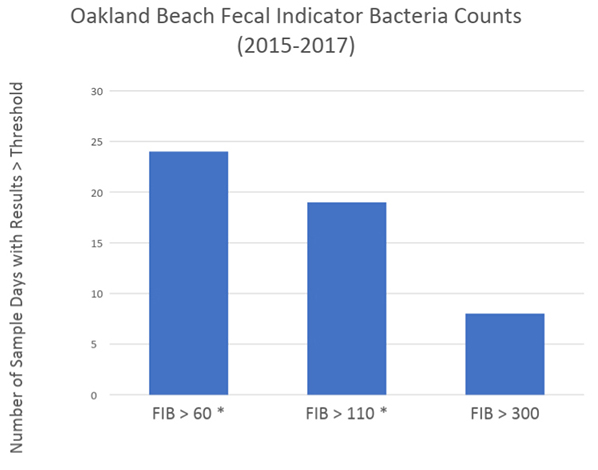

For the past 12 years Oakland Beach also has consistently exceeded recreation standards for enterococci. Poucher said the beach has one of the highest closure rates of all licensed beaches in the state.

From 2015-2017, Oakland Beach water samples tested above 60 cfu 24 times, above 110 cfu 19 times, and above 300 cfu eight times, according to DOH and COA data. The beach was closed eight times in those three years.

In the Narragansett Bay watershed, where Oakland Beach is, bacterial pollution is often present because of stormwater runoff and overflows from wastewater treatment facilities. Contamination from these sources is magnified by impervious surfaces such as concrete and asphalt and precipitation. The upper estuary in Narragansett Bay in particular suffers from high pathogen loading.

Poucher noted that City Park Beach, on the opposite shore from Oakland Beach, has significantly fewer closed beach days. The City Park Beach shore is parkland and the area is less developed than that around Oakland Beach. It also has fewer visitors.

Going back to data from 2006, Poucher said it doesn’t appear the water-quality problem at Oakland Beach is getting any better. She and the others who competed the “Research Needs for Marine Beaches” project hope their researched leads to significant improvements.

It’s absolutely disgusting how this state can call itself the Ocean State (but really not) and have so many beach closures. Something must be done about stormwater runoff to start. Look to Bristol for how they cleaned up its town beach.

Data but no specific recommendations for solving the problem. No examples of how other beaches have solved their problems. No facts for people to grasp and relate to their behavior or the behavior of the government or the economy. Frustrating article.