Threats Remain to Atlantic’s Only National Monument

March 13, 2019

PROVIDENCE — The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, the only national monument in the Atlantic Ocean, remains controversial more than two years after it was designated by President Obama in September 2016.

Fishermen brought suit to overturn the designation — the suit was dismissed last October, but it’s being appealed — President Trump has threatened to use his executive authority to revoke the designation, despite uncertainties as to whether he can legally do so, and the Interior Department has recommended that the Trump administration reopen the monument to commercial fishing.

Peter Auster, however, argued in a lecture at Roger Williams Park Zoo on Feb. 28 that the 4,900-square-mile area about 150 miles off Cape Cod is deserving of protection because of its high species diversity, wide variety of habitats, and its numerous creatures that are sensitive to disturbance.

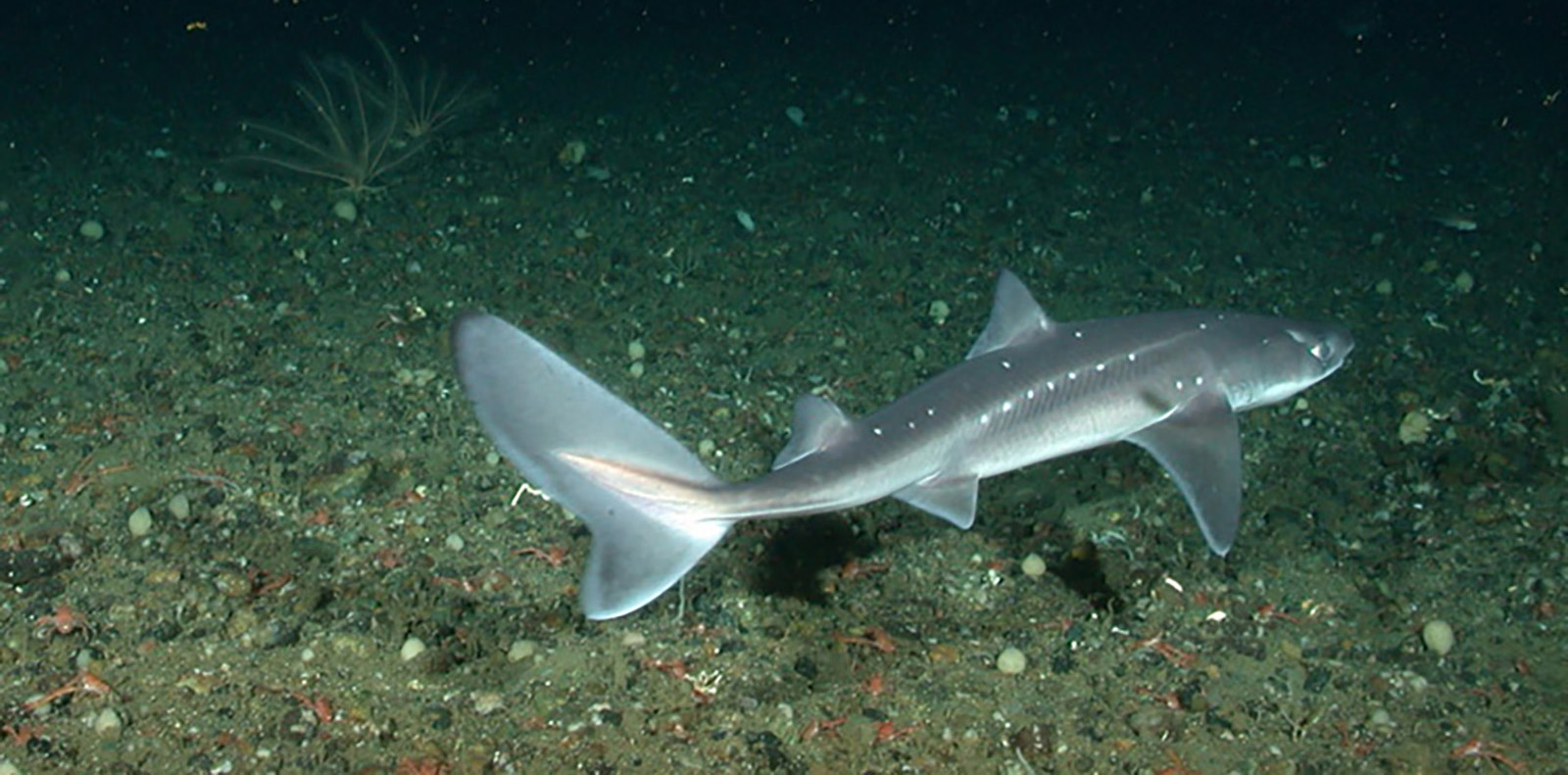

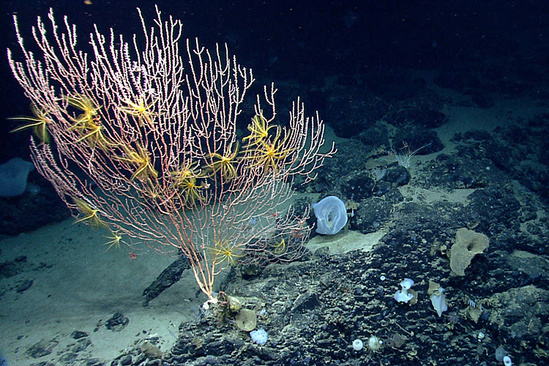

A senior research scientist at Connecticut’s Mystic Aquarium, Auster was a key player in building the scientific case for why the area should be designated a national monument. He has led multiple research projects to explore the area using submersible vessels, remotely operated vehicles, and autonomous vehicles, all of which have revealed an unusual array of marine life, from “Dr. Seussian species” of fish to dozens of kinds of deep-sea corals.

“A dive into the canyons and seamounts demonstrates the magic of the ocean,” he said. “There’s a whole garden of organisms that live there.”

The monument includes a portion of the edge of the continental shelf, where the seafloor drops sharply from a depth of about 600 feet down to 3,000, and where four extinct underwater volcanoes jut upward from the seafloor. The monument got its name from those underwater volcanoes — called seamounts — and a number of canyons carved into the shelf edge by ancient rivers.

“Those canyons and seamounts create varied ecotones in the deep ocean with wide depth ranges, a range of sediment types, steep gradients, complex topography, and currents that produce upwelling, which creates unique feeding opportunities for animals feeding in the water column,” Auster said.

Using colorful photographs of rarely seen creatures to illustrate his presentation, Auster called the area a “biodiversity hot spot,” noting that at least 73 species of deep-sea corals live in the area, including 24 that were found there for the first time during a research expedition in 2013. Many of those corals serve as hosts to other creatures — crabs, shrimp, and starfish, for instance — that are only found on those particular corals.

New England Aquarium researchers have found that the monument’s surface waters serve as feeding grounds for an abundance of whales, sea turtles, sharks, and seabirds, as well as fish that migrate from the deep water to the surface every day to feed.

In addition, Maine Audubon recently discovered that the monument area is where many of the region’s Atlantic puffins spend the winter. And researchers from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Mass., found that significant numbers of the extremely rare True’s beaked whale, one of the deepest diving marine mammals in the world, spends the summer in monument waters.

Despite these recent discoveries, scientists say there is still a great deal to be learned about the area.

“We don’t yet know everything we need to know to manage the monument,” Auster said.

On his scientific to-do list is an assessment of the biological diversity of the area and how it’s distributed in the monument; an assessment of ecological change over time; a better understanding of species interactions; and an assessment of how the region has recovered from natural and human-caused disturbances.

While the status of the monument remains in limbo, a number of additional threats may be lurking. So far, commercial fishing has only impacted the shallow areas of the monument on the continental shelf, but Auster said there are increasing efforts to fish in the deeper waters. In addition, the Trump administration is advocating for expanded oil and gas exploration in the waters off the East Coast, and the growing seabed mining industry may see the seamounts as potentially valuable sites for methane hydrate mining or manganese crust mining.

While Auster seems somewhat confident that the monument designation will hold, and he’s already working on making the case for a second marine national monument in the Atlantic — this one at Cashes Ledge in the middle of the Gulf of Maine — he acknowledged that there are influential political forces at work that could derail the monument designation.

“Like every monument, there are people who suggest that it isn’t a good thing to conserve examples of our natural heritage for future generations,” Auster said. “The end of this story remains to be written.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.