Supporters Rally to Push New Bottle Bill, Promising Less Litter and More Money for Recycling

March 11, 2023

PROVIDENCE — The wheels are turning, and even accelerating, toward a change in Rhode Island law that could help keep plastic, metal and glass trash off roadsides and beaches, and also force beverage distributors to help pay for the costs of recycling, which now fall entirely on communities and taxpayers.

One mechanism for a cleaner state and enhanced recycling would be a new beverage container deposit-and-return bill, or “bottle bill,” now before the General Assembly. Supporters say the bill (H5502) is designed to be the gold standard of these laws: effective, convenient, and equitable to all.

The new bottle bill, despite its alliterative nickname, covers a deposit-and-return system for bottles and cans made of glass, metal, and plastic, containing most beverages, but not including milk, juice boxes, or juice pouches.

The bill contains provisions designed to ease the objections of opponents of bottle bills defeated repeatedly in the past. These new provisions include an opt-out for small retail stores, and grants to help businesses adapt to the system, like purchase of “reverse vending machines” that accept returns.

A broad coalition of environmentalists calling itself the Zero Waste Coalition is pushing the House bill, sponsored by Rep. Carol Hagan McEntee, D-South Kingstown.

Kevin Budris, advocacy director for Just Zero, echoed the views of other supporters when he said the time is ripe for Rhode Island to join the 10 other states and many foreign countries that require container deposit-and-return programs.

“There is an increasing recognition in Rhode Island” — by ordinary people, environmentalists, and legislators — “that a bottle bill is the proven solution to waste, and to stem the tide of plastic production and pollution,” Budris said. “This is a great piece of legislation and this is the year. Rhode Islanders are ready for action. There is a broad coalition working to get this bill across the finish line.”

A longer-term objective of the bill is to require that, over the years to come, a higher percentage of bottles and cans bought and returned in Rhode Island must be cleaned, sanitized, and reused. The bill would require 50% of containers to be reusable by 2034. The goal is to reduce the manufacture and use of virgin plastics for new containers. Collecting and isolating beverage containers through a deposit-and-return system keeps them clean, untainted by non-food liquids, and safe for refill and reuse, according to the bill’s supporters.

“This bill could get us to a 90% redemption rate [for beverage containers],” Budris said. “This sets a pathway to reusable beverage containers, which is the ultimate goal.”

A coalition of at least 13 environmental organizations that are pushing the bill held an information session and pep rally March 9 at the Statehouse library. Among the speakers was McEntee, the House sponsor of the bill, and Sen. Bridget Valverde, D-North Kingstown, a supporter of strong recycling who promised the group that a corresponding Senate bill would be coming soon.

McEntee said she has shepherded about four previous and unsuccessful bottle bills through the General Assembly. Like other speakers, she said residents and legislators are primed this year to push a bill into law.

“The time has come. We need to get forceful with this,” McEntee said.

She, along with Valverde, said constituents are really aggrieved by litter from bottles and cans, adding, “Even those opposed to a bottle bill agree that we have to do something about plastic waste.”

Braced for opposition

McEntee predicted strong opposition to the bill, particularly from major beverage producers. “The business community is saying a bottle bill is too difficult; we don’t want dirty bottles coming back to our stores; we don’t have room for them,” she said. “I get that, but we don’t have a choice.”

Jed Thorpe, state director of Clean Water Action, agreed that “opposition will be fierce, especially from big beverage companies” such as Coca-Cola, Nestlé, and Anheuser-Busch. As an example, Thorpe said large beverage companies spent $7 million in 2015 to defeat a ballot question in Massachusetts that asked voters to modernize that state’s existing container deposit-and-return law.

Valverde said she grew up in Connecticut, where there is a bottle bill, and people considered it no big deal to save and return their beverage bottles and cans.

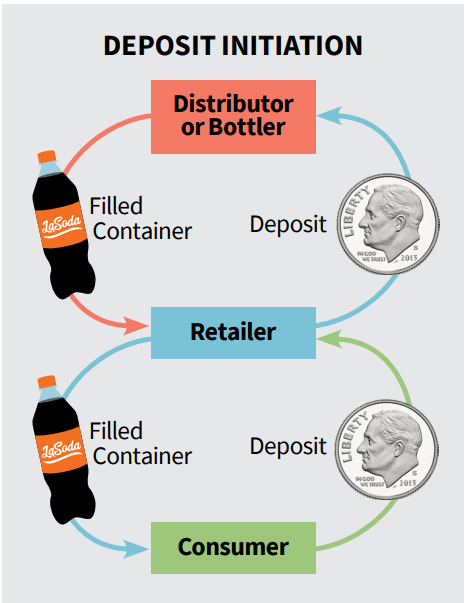

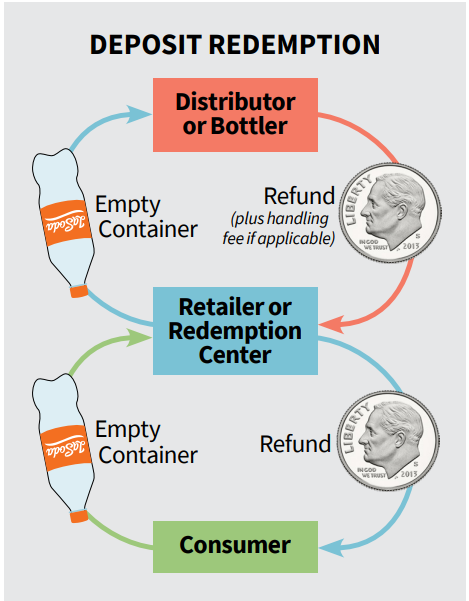

Under the Rhode Island bill, retailers who sell beverages would be required to accept empty bottles and cans and to refund 10 cents per container to the customer. Containers could be returned for the deposit to any retailer that sells the beverage, regardless of where the beverage was purchased, with some exceptions. Containers may be returned to the retailer or to freestanding redemption centers that could be set up around the state.

Retailers ultimately would return the used bottles and cans to distributors or bottlers. They, in turn, may sell the containers to recyclers. Since this is a stream of once-used beverage containers, the long-term hope is that recyclers clean and sanitize the containers and make them available for refill and reuse, slowing the need to produce more new containers.

There are exceptions in the bill, some of them to assuage worries raised in arguments over previous bottle bills. Retailers with less than 2,000 square feet of space would be allowed to opt out of the program. Restaurants, bars, and hotels would be responsible only for bottles and cans sold to their own customers; they would not be required to accept containers from the general public. The law would apply to bottles up to 3 liters in size, a concession to businesses that deal with much larger containers of bottled water, of the size for water coolers. The bill covers the controversial “nips,” the nickname for tiny single-shot containers of alcoholic beverages that have turned into a litter plague.

Also, some income from the law, in the form of unclaimed deposits, would be made available as grants for various purposes to support the intent of the program. Budris said, for instance, a retailer might get a grant to expand their store to allow for empty bottle storage, or to buy a reverse vending machine, which accepts empty bottles and issues refunds.

Under the bill, beverage distributors would be required to pay a handling fee of 3.5 cents per container to the state, to help cover the costs of the program. Tagging the beverage producer to help pay the freight for disposal of its packaging is known as the principle of extended producer responsibility. Under this principle, which has been applied to hard-to-dispose products like paint and mattresses, producers of goods accept some responsibility, cost, and labor to dispose of products and packaging.

“The point of the handling fee is to fund the system,” Budris said. “The bottle bill seeks to shift the cost of recycling off of state residents and on to the corporations that profit from the single-use beverage containers that are polluting the environment.

“The beverage industry has been historically hostile to bottle bills because they want to avoid that cost. But handling fees give [distributors] some skin in the game. They have to bear their part of the burden” of recycling cost and roadside trash.

Also, distributors would be responsible for record keeping of containers sold and returned, and they would have to turn over unclaimed deposits to the state Division of Revenue. That money would go to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management to manage the system and also to help pay for grants.

More effective recycling

Experts in plastics say unequivocally that plastic recycling — never higher than 9% in the United States — cannot solve plastic pollution or lead to the cleaning, refilling, and reuse of plastic beverage and food containers. That is partly because recycled plastics often are contaminated with unsanitary material such as motor oil, solvents, and cleaning products.

The Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation receives plastics at its materials recycling facility in Johnston via curbside recycling, which does not isolate food and beverage containers from dirtier plastics, glass, and aluminum. Consequently, the facility ends up crushing and bundling much of the collected material and selling it to recycling firms to be “downcycled” into lower-grade materials not fit for reuse for food or beverages.

Clean Water Action also notes that “right now in Rhode Island, all of the glass that is recycled [through curbside pickup] is not actually being turned into new bottles but is instead being used as landfill cover or in road construction.”

Jared Rhodes, director of policy and programs for the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation (RIRRC), said an effective container deposit-and-return system could have the effect of reducing the flow of recyclables to the facility and consequently reduce the revenue RIRRC gets from selling those materials.

“Resource Recovery would expect the implementation of a bottle redemption program in Rhode Island to reduce the amount of mixed recyclables flowing into our materials recycling facility and subsequently the amount of marketable commodities and associated revenues,” Rhodes said.

He added, “Resource Recovery last estimated the potential revenue impact of a RI bottle redemption program in FY22. At that time, Resource Recovery projected what would now be a 4.89 % reduction when compared against our audited FY 22 revenue total. This would be considered a material change by accounting standards.”

Budris noted that, like other businesses, RIRRC could apply for grants through the new program, possibly for purposes like upgrading its recycling machinery or installing container redemption machines.

Distractions from litter tax

A topic that often arises when the General Assembly is looking at bills to rein in roadside litter is the Litter Control Tax, usually just called the “litter tax.” Passed in 1984 under Gen. Laws § 44-44-10 and amended over the years, the Litter Control Tax is imposed, via annual permits based on gross receipts, on businesses that sell food or beverages. In its early years, the Litter Control Tax helped pay for some public educational programs to discourage littering. Tax revenues were deposited in restricted receipt accounts. The law was amended in 1995 to move litter tax revenues into the state’s general fund.

The tax is an irritant to food and beverage business owners, particularly since revenues are not used specifically to combat littering. (The litter tax and a separate Beverage Container Tax raised $3.5 million in 2020, $3.9 million in 2021, and $3.5 million in 2022, but the revenues from the two taxes cannot be reported separately, said a spokesperson for the state Division of Taxation.)

An appropriations bill now before the General Assembly (H5200) would repeal the hated litter tax, raising speculation that the proposed repeal could be a sweetener designed to help beverage retailers swallow the task of adapting to a bottle bill.

During arguments before the General Assembly last year over bills to ban single-use plastic bags used by retailers (which passed) and to ban nips (which didn’t), liquor store owners and beverage business people said the solution was not to ban bags and nips, but to enforce anti-littering laws, with help from the litter tax revenues to pay for trash barrels, billboards, and public education. Punish the litterers, not the liquor store owners, they argued.

Thorpe, of Clean Water Action, said the litter tax argument was a distraction from real solutions by claiming litter was a problem of bad people making bad choices. No amount of trash barrels and billboards, Thorpe said, could get remotely as close to diverting trash from cast-off beverage containers as a bottle bill could.

An interesting twist to bottle bill theater in Rhode Island in this year’s session is a bill introduced by Rep. David Bennett, D-Warwick, that would apply a deposit-and-return system only to nips. Empty nip bottles carpet roadsides and outdoor places in all parts of Rhode Island, enraging many residents.

Bennett’s bill (H6054) would place a deposit of 25 cents on nip bottles and establish a full deposit-and-return system like the one proposed in the larger bottle bill. In addition, Bennett’s bill would require that all nips must be no smaller than 2 inches by 2 inches, which is larger than many nip bottles now on liquor store shelves. The larger size would make it more feasible for nips to be captured in the sorting process at the materials recycling facility at the state landfill. Now, landfill operators say, nips slip through too-wide grates in the sorting equipment and cannot be collected and bundled with waste plastics or glass.

A popular liquor sold in nips in Rhode Island is Fireball; empties are famous for appearing on the ground all over the state. Bennett said officials at Sazerac, the bottler that makes and sells Fireball, have told him the bottle will be redesigned and re-introduced in a larger size in the next few months.

A 1989 law that has gone unenforced for three-plus decades likely makes the sale of nips illegal in Rhode Island.

Members of the Zero Waste Coalition include Audubon Society of Rhode Island, Environment Council of Rhode Island, Conservation Law Foundation, Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council, Clean Water Action, Blackstone River Watershed Council, Just Zero, Save the Bay, Friends of the Saugatucket, Ocean Recovery Community Alliance, Be the Solution to Pollution, Clean Ocean Action, and Zero Waste Providence.

One wonders why “nips” are even allowed anywhere. They not only produce litter as the article explains, but almost as important but scarcely mentioned, is that they are an obvious contribution to driving while drinking and getting rid of the evidence, “nip and toss”.

Nips are only of value to liquor manufacturers and distributors and people that shouldn’t have them in the first place alcoholics.

If Rhode Island is serious about reducing its roadside litter problem we need a bottle bill especially for smaller size bottles most litter found is of.bottles a pint or less in size as the size decreases the amount of litter generated increases.

A bottle bill will put a so called bounty on the recovery these products.

A benefit of this bill not normally discussed is the reduced amount of money expended to clean the environment.

I’m all in favor of a bottle bill but instead of going back to grocery stores, the bottles should go to redemption centers. Every town should have a redemption center. Used bottles that are not rinsed properly or found on the side of the road are filthy many times and they are smelly and not very hygienic to bring into a clean store.

RI is a lovely place, but a trashed state on display for the world. 138 towards Newport has had trash/bottles on it for almost 6 months. Plus people get high and roam drunk daily in and around the forests, parks and preserves in Washington county and throw out whatever they please.

The State cannot keep up, many of the towns do not have the staff to do much litter pickup and rely on volunteers. And if there are not enough volunteers – well too bad just deal with it.

One of the organizations is “Ocean Recovery Community Alliance” NOT “solution” Thanks!

there is now a hearing scheduled on the bill H5502 on Thurs 3/23 in the House Lounge at the “rise” – often about 4:30pm.

Its a complicated bill intended to address a lot of issues.

I’m not sure why Resource Recovery Corp is negative – wouldn’t more bottles/cans getting recycled both enhance their revenue and extend the landfill life?