Sewage Sludge Repackaged as Garden Fertilizer Tests Positive for Toxic Chemicals

February 10, 2022

Sewage sludge that many wastewater treatment facilities lightly treat and then sell throughout the United States as home fertilizer contains concerning levels of controversial substances.

Last year the Sierra Club and the Michigan-based Ecology Center found toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, better known as PFAS or “forever chemicals,” in nine fertilizers made from sewage sludge — commonly called “biosolids” in ingredient lists — and mapped businesses selling sludge-based fertilizers and composts for home use.

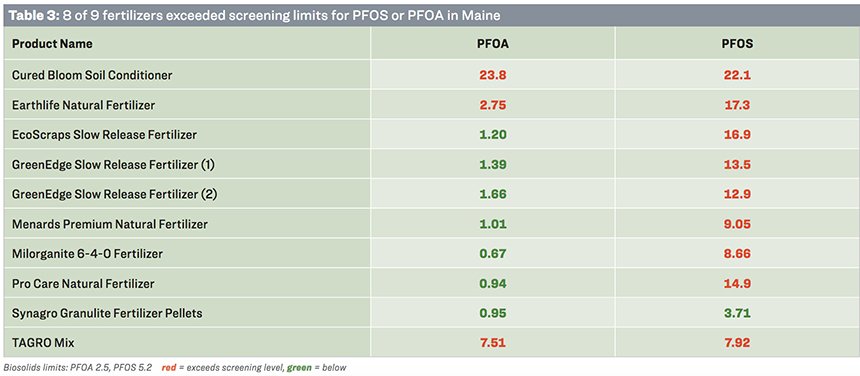

Eight of the nine products tested exceeded the screening guideline for perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) or perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) set in Maine, the state with the strictest safeguards for PFAS levels in sludge spread on agricultural lands. PFOS and PFOA are two of the more dangerous forever chemicals. They are no longer manufactured in the United States, but they are still produced internationally and can be imported in consumer goods.

Overall, there may be as many as 5,000 of these manufactured chemical compounds on the market today. They persist in the environment and in our bloodstreams, as these compounds suffer no degradation in light or air or through biological processes. Since they are highly mobile, their contamination is spreading through soil into ground and surface waters and accumulating in fish, shellfish, wildlife, and crops.

PFAS levels in these home fertilizers and compost raise concerns that the chemicals could be contaminating fruits and vegetables and could be harming those who eat them, according to those behind the 2021 report. Forever chemicals, which have been linked to cancer, thyroid disease and weakened immunity, coat food packaging, fabrics, and waterproof clothing. They are used in electronics, firefighting foam, anti-fogging sprays, waxes, microwave popcorn bags, some pizza boxes, and countless other items. They have seeped into drinking water supplies in both Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Sludge in the Garden: Toxic PFAS in Home Fertilizers Made From Sewage Sludge noted many of the products made from sewage sludge are labeled as “eco,” “natural” or “organic” — even though biosolids are not allowed to be applied on farms growing certified organic produce.

Sierra Club and Ecology Center researchers bought nine fertilizers: Cured Bloom; TAGRO Mix; Milorganite 6-4-0; ProCare Natural Fertilizer; EcoScraps Slow-Release Fertilizer; Menards Premium Natural Fertilizer; GreenEdge Slow Release Fertilizer; Earthlife Natural Fertilizer; and Synagro Granulite Fertilizer Pellets.

Of the 33 PFAS analyzed in the products, 24 were detected in at least one product. Each product contained from 14 to 20 detectable PFAS.

Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) wastewater treatment facility sludge regulations allow land application of sludge as fertilizer and soil amendment.

However, most of the sludge generated in the state is either incinerated or buried in a landfill, according to an agency spokesperson. Domestic septage — liquid or solid material removed from a septic tank, a cesspool, a portable toilet or a marine sanitation device — is not considered sludge.

Another DEM spokesperson noted the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is currently conducting a risk assessment study for PFAS in biosolids. He said the DEM “is waiting for that work to be completed before making any determination on the issue.”

“As it stands, however, DEM does not require testing for PFAS in sewage sludge,” he wrote in an email to ecoRI News. “The only municipality testing for PFAS in sludge is Bristol, which has a permit with MADEP [Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection] because Bristol’s sludge is used as compost in Massachusetts.”

Massachusetts has the long-term goal of “virtually eliminating” PFAS in biosolids, but is still developing a screening limit and management plan to achieve this goal. Two-plus years ago, PFAS were found in a biosolids fertilizer the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority has been selling for nearly three decades.

Connecticut doesn’t allow the use of biosolids as fertilizer.

The North East Biosolids & Residuals Association, a corporate-supported nonprofit that promotes the use of sewage sludge and other wastes as fertilizers, soil amendments and sources of energy, claims wastewater, septage and biosolids are not PFAS sources.

“Wastewater treatment processes do not utilize PFAS chemicals,” according to the New Hampshire-based organization. “Only in a few worst-case scenarios have wastewater and biosolids been implicated in PFAS water contamination at levels of concern.”

The EPA has a health advisory of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. The maximum contaminant level in Massachusetts for its six listed PFAS is 20 ppt. Rhode Island follows the federal advisory.

Maine is one of the only states that has guidelines to prevent biosolids from contaminating agricultural lands and groundwater. It requires all biosolids be tested for three PFAS prior to land application. When concentrations exceed a screening limit of 2.5 parts per billion for PFOA, 5.2 for PFOS and 1,900 for perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS), agricultural fields must also be tested to ensure repeated applications haven’t led to soil concentrations over the limit.

Forever chemicals, which can be highly toxic to humans, are virtually unregulated, meaning industries are legally allowed to flush PFAS down wastewater drains where they settle out in the solid materials during wastewater treatment.

The report’s authors have called for stricter regulation of sludge, for the industry to address its PFAS waste, and for regulators to impose limits for the entire class of PFAS compounds instead of just a few.

Sonya Lunder, senior toxics policy advisor for the Sierra Club, said the EPA and states need to take “swift action to enact strong standards to safeguard us from toxic PFAS continuing to flow into our wastewater and keep contaminated sewage wastes out of home gardens and farm lands.”

“While chemical companies have profited handsomely from PFAS chemistry, our drinking water, farms, dairies and the American public have paid the price,” she said.

The EPA requires biosolids be tested for phosphorus, pathogens and nine heavy metals before application, but the federal agency does not set any limits for PFAS.

In 2019, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection tested 44 fields sprayed with biosolids and consistently found alarmingly high levels of forever chemicals in soil, in cows and in at least one farmer’s blood.

Of the 44 samples taken from farms and other operations that use fertilizer and compost made from sewage sludge, all contained at least one PFAS. In all but two of the samples, the chemicals exceeded safety thresholds for sludge that Maine set in 2018. The Pine Tree State developed the standards after milk from cows on a dairy farm that spread biosolids were found to be contaminated with high levels of PFAS.

Last month, cattle from a small Michigan farm that sold beef to schools and at farmers markets tested positive for unsafe levels of PFAS.

Sewage sludge is expensive to dispose of because it must be landfilled or incinerated, but the waste management industry, according to a 2019 story in The Guardian, is increasingly using a money-making alternative: repackaging the sludge as fertilizer and injecting it into the U.S. food web.

About half of the sewage sludge produced by U.S. wastewater treatment facilities is spread on farmland and gardens. Biosolids hold nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients that help crops grow.

This practice, according to the story, is behind a growing number of public health problems. Spreading pollutant-filled biosolids on farmland is making people sick, contaminating drinking water, and infiltrating crops, livestock and humans with pharmaceuticals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, and forever chemicals.

While studies have found that fruits and vegetables absorb forever chemicals, there are no standards for PFAS in food. The presence of perfluoroalkyl acids in biosolids destined for use in agriculture has raised concerns about their potential to enter the terrestrial food chain via bioaccumulation in edible plants, according to a 2013 study.

“PFAS chemicals pose huge, complicated, and expensive management challenges at the end of their useful life,” according to the 20-page report. “While this investigation highlights the challenges posed by wastewater disposal and biosolids reuse, it is important to note upfront that it is far simpler, less expensive, and more effective to stop using the chemicals in most consumer and industrial uses, rather than attempt to contain and manage wastes.”

Editor’s note: On April 20, Maine Gov. Janet Mills signed into law a bill that is the first in the country to ban the spreading of sludge and sludge-derived compost as fertilizer, because of concerns about PFAS contamination.

Thank you ECORI News for bringing this to the public’s attention!

What next?

forever chemicals last ‘forever’…..we certainly do not want to grow food in this!

What is the point of paying for the work of federal agencies like the EPA, and the Department of Agriculture, as well as state agencies to protect consumers from contaminants when they ignore major problems, provide lax or no guidance to states and back off if a big corporation cashing in on selling these materials to states and fertilizer manufacturers challenge them? Why aren’t states requiring higher standards, labeling food products that are coming from states that do not test food they export to other states, and requiring stores to remove or clearly label chemicals that contain “forever chemicals”? Climate change will be a major world wide challenge to agriculture and the food supply. Why add the completely avoidable health problems of these chemicals being freely used in agriculture?