Rats! Municipalities Beef Up Their Efforts to Control the Wily Rodents

August 31, 2023

CRANSTON, R.I. — As the COVID-19 pandemic raged across the state, cities and towns grappled with a different widespread situation. As restaurants closed from government-mandated shutdowns and businesses pivoted en masse toward a remote work environment, municipalities everywhere saw a growing number of complaints about everyone’s favorite neighbor: the common brown rat.

Their appearance as pests is both ubiquitous and unmistakable; nearly everyone has seen one somewhere at some point in their lives. Similar in appearance to mice, rats have dense short fur that can range in color from brown to gray, cute round ears, whiskers and a hairless tail. On average, a fully grown rat is 16 inches in length and can weigh as much as a pound or more.

Rats are having a big impact in Rhode Island. Since 2020, residents in Pawtucket, North Providence, East Providence, Johnston, and Cranston have all made headlines expressing concerns over their neighborhoods’ rat problems, and their scramble to get the rodents under control.

“I’m not kidding, it’s almost every house I go to,” said John Donegan, a City Council member. “When someone answers the door and I ask them if they have any concerns or issues, three out of four people will say rats. In certain neighborhoods, it’s every single person.”

Donegan was first elected to the City Council in 2018, representing the city’s third ward. His ward includes a number of working-class neighborhoods in north-central Cranston, close to the Providence city line, such as Laurel Hill, Arlington, and the area around Stebbins Stadium.

The city’s rat problem isn’t new, said Donegan, it’s something he’s routinely heard from constituents since assuming office. In 2019, when he was still a freshman council member, Donegan said he reviewed the last five years of data from the rodent baiting program, which offers inspections and baited rodent traps to any homeowner, free of charge, and found that his own ward had the most requests for rat traps.

There was a huge surge in complaints during COVID, he said. When restaurants had to close during the pandemic, rats lost an easy source of food and had to disperse into other areas to eat. It coincided with a time where people were home more often, generating more trash in residential areas and creating what Donegan said was “kind of a perfect storm.”

“I just feel for the people that tell me, ‘John, I can’t sit in my backyard on a Saturday during the summer because there are rats running around in the middle of the day,’” Donegan said. “Or the people that tell me, ‘We saved up for years to buy a house here in Cranston and we just moved to this place and we really love it, but there are rats running through our yard and my dog catches five rats a week.’”

Rats’ persistence as human pests lie squarely within their unique ability to adapt and survive. They’re primarily nocturnal creatures, only venturing out from their underground nests, called burrows, at night to scavenge for food. Their nocturnal clock and underground lifestyle help protect them from their natural predators, which tend to be a lot of the natural predators of most mammals: hawks, owls, coyotes, foxes, and everything else in the ecosystem hellbent on eating them. Living closer to humans allows them to find easy food sources and dodge their natural predators, allowing their population to balloon.

Rats will eat almost anything; one study on the contents of rats’ stomachs suggests the rodents can digest some 4,000 food items, and their specific diet will depend on their environment. Away from human cities and development, they can eat a variety of plants and whatever protein source they can get their paws on — fish, lizards, chicks, or even other rodents. In cities and towns, there’s one food source they love and can easily access above all others: trash.

For rats, American cities and towns are the promised land. On average, Americans generate 4.5 pounds of trash per day per person. It’s estimated the United States wastes 60 million tons of food a year — about 325 pounds of waste per person every year.

When it comes to trash, rats are heat-seeking missiles and it doesn’t take much to attract and build a new rodent infestation. A single backyard can sustain a colony of up to 50 rats. While it increases in the warmer months, their breeding cycle is not attached to any one season. On average, a pregnant female rat will give birth to around eight pups, and they are capable of having up to seven litters a year.

“It’s a very slow, slow cooking, it’s like putting a big kettle of water on a low span,” said Robert “Bobby” Corrigan, noted rodentologist and pest control expert, describing how quickly rats can spread. “It’ll be a long way off, but eventually we’re going to end up with a spillover.”

Despite their ubiquity in our cities, rats aren’t really something most local or state governments bother to put resources toward or keep tabs on. When a city somewhere in the country has a rat problem, Corrigan is usually the guy they call. He’s one of the few people who has spent his life chasing rats. “I just wanted to branch out,” Corrigan said in a phone interview earlier this year. “I was an entomologist at first and I wanted to study something nobody else did. One thing led to another, and I’ve never looked back.”

Rats also carry disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists dozens of different diseases associated with rats and other rodents on its website, but the actual number of diseases carried by rats is likely to be much less dramatic. Studies on New York City rats show they carry multiple bacteria like E. coli and salmonella, and in some cases diseases such as leptospirosis and hantavirus.

The diseases carried by rats can spread to people directly, typically via direct contact with the rodents, their feces, urine or saliva, or bites. Rats can also carry fleas, ticks, and mites, which can spread their own diseases between rodents and people.

The same traits that allow rats to thrive — their ability to eat a wide range of food sources, quick turnaround times for breeding, their overall ability to adapt to their environment — has made tracking their movements impossible. There is no way to track rats, said Corrigan, and there never will be. The best most cities can do is to break local neighborhoods into quadrants and use statistical sampling techniques to get a rough idea of how prevalent rat populations are in that area.

Their movements typically mirror new developments, apartments or restaurants. The more people coming in, the more trash is generated, the more food sources out there exist to attract rats.

“We can say which areas of the city tend to have the highest rat complaints, or the highest rat sightings, and not worry about the number,” Corrigan said. “If it’s a lot of complaints, a lot of rat sightings, that needs attention; forget about how many rats.”

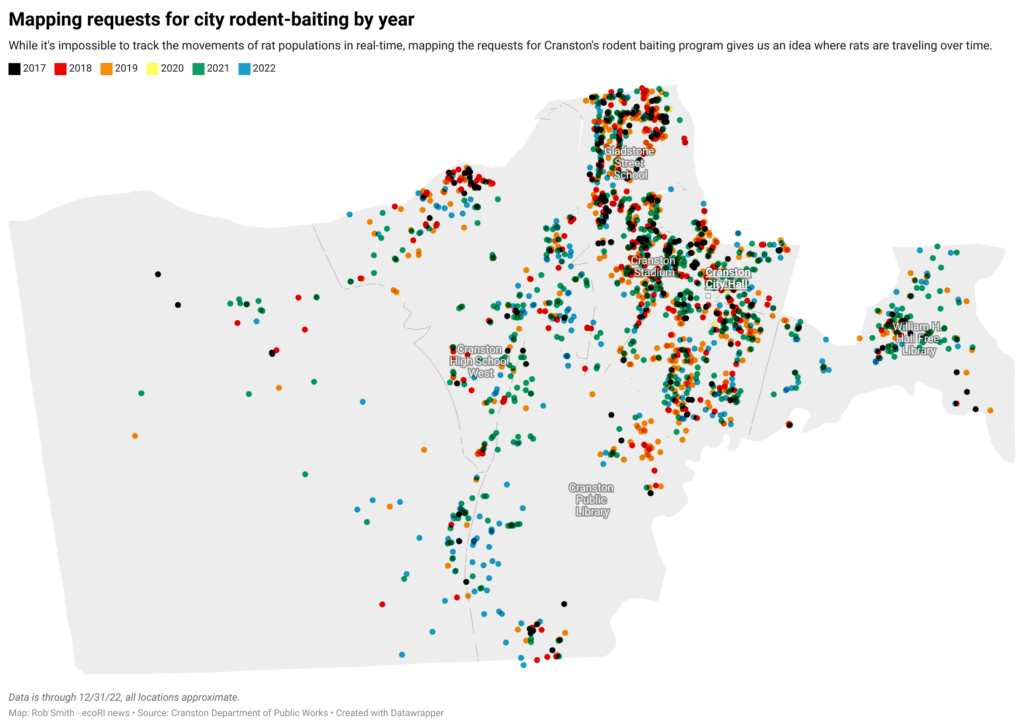

Through several public records requests, ecoRI News has obtained the last five years of data from Cranston’s rodent baiting program — the city’s master list of what addresses have requested city rat services, when they requested the services, and when the Department of Public Works fulfilled the request. While it’s almost impossible to track individual rat populations, tracking complaints and requests for traps can suggest when and where our rodent friends hang out and where they are going.

Data from the records show that in the years following the pandemic, the city’s rodent baiting program experienced less a surge and more a deluge of new requests for rodent inspections and baiting. In 2021, 618 new addresses requested rodent baiting from the DPW, more than double what the city recorded in 2020. That number only declined slightly the following year, with 511 new addresses requesting baiting and traps for the first time in 2022.

The good news for this year is, the city is on track to see a sharp decline in new requests for rat traps; as of June 1, only 89 new addresses have requested traps, a trend closer to the program’s average before the pandemic.

Meanwhile, mapping that same data — plugging every address into a map of the city — shows that Cranston, when it comes to rats, is very much a tale of two cities. The greatest number and concentration of requests for the rodent baiting program are clustered in the city’s working-class neighborhoods in central Cranston, in areas close to the city line in Providence, and the Edgewood area in eastern Cranston. The neighborhoods that Donegan represents as the Ward 3 council member still rank high.

But those rats aren’t staying put; they’re on the move every year. Data on requests from 2021 and 2022 shows a visible trail of rat trap requests spreading south toward Warwick, close to major roadways, and another line of trap requests making their way west, toward some of the city’s wealthiest suburbs, an area that has traditionally been light on rat sightings.

“[Rats] have been climbing pretty steadily, especially in the Northeast sector, from Boston down to D.C.,” Corrigan said. “I track them every year in terms of city complaints and surveys, and they’ve been increasing over the past 10 years by 15%, easy. In some areas they’ve increased up to 30%.”

Rats aren’t just a growing problem in Cranston or Rhode Island. In his travels, Corrigan said he has seen an uptick in rat complaints around the world, from Europe to New Zealand. But ultimately the reasons for the global upward trends in rats remain unclear.

Climate change could be a contributing factor, as New England’s snowy winters and sub-zero temperatures gradually become a distant memory. Despite their fur coats, rats aren’t built to thrive in extreme cold temperatures. Unlike other mammals, they don’t hibernate in the winter either.

Instead, rats compensate with their underground burrows, which are designed to retain heat for the nest, and their high metabolism to keep them warm. Their reproductive cycle typically slows down in the winter. For rats it makes more sense to wait until spring, rather than expose their pups to possibly dangerous cold temperatures.

It’s far riskier for rats to leave their nest during winter’s colder months; it gives them a limited amount of time to forage for food and make their way back to the nest before freezing to death or dying from exposure. As the region’s winters become more and more mild and and snowstorms become scarce, it’s one less thing keeping rat populations in check.

Increased development and construction — of housing subdivisions, of office space, of new restaurants — could also be a major factor, according to Corrigan. New construction means more people, and more people means more food waste and trash, and more garbage means rats have the perfect conditions to thrive.

“The rats are very unforgiving when we make mistakes with our trash, given that we’re all linked together,” Corrigan said. “It’s about density of people, it’s about our trash, it’s about construction, it’s about old sewer lines.”

Meanwhile, in recent years, Cranston has stepped up its rodent control in a big way. This year the City Council allocated a $25,000 budget for the rodent control program, nearly three times what the program was allocated in 2017. The program still has a single employee, however.

In 2019 the City Council also passed a new rodent control ordinance, sponsored by Donegan, with a little teeth. Under the ordinance, property owners can be cited and fined for not acting quickly enough to a known rodent infestation. They can be fined $50 every 30 days until the DPW director deems the property free from rats.

“It was not meant to be a revenue generator,” Donegan said of the law. “It isn’t meant to give people a hard time for not maintaining their property. I mean things like trash out in the yard, piles and piles of debris that could lead to rats burrowing and whatnot.”

Other municipalities in Rhode Island’s urban core are following suit. In June, WJAR reported that Johnston was launching a rodent control program for residents with single-family homes. The town has reported an increase in complaints since the pandemic, especially in the eastern, denser part of town near the Woonasquatucket River. Johnston is expected to gauge the success of the program in late September.

Unfortunately, the grim reality is, no matter what measures cities and towns take to control their rodent populations, we’re always going to be living with rats. There are too many unseen places, sewers, rivers, and debris piles, where rats can hide and propagate. For pest management experts, the name of the game is population control; keep rat numbers down below a certain amount so they don’t become a public health risk or nuisance.

“Rats are an issue, and they’re an issue that has public health implications,” Donegan said. “But even from a quality-of-life standpoint, people deserve better.”

Everyone wants to obliterate feral cat populations but with a well controlled TNR program, the rat problem subsides. It will never go away but the cats will keep it under control. I used to have a feral colony that I tended to, fed daily and all were captured and ‘fixed’. The bakery across the street from where I lived at the time no longer had a major rat problem.

We need more coyotes

We have 2 feral / TNR barn cats and they will rarely go after the rats. The rats are bigger than squirrels and perhaps faster and travel underground preferable to the trees. Our barn cats completely decimated the chipmunk, mouse, and vole populations. Kings of the barn! Rats are so big when I find them dead their body is wholly intact. Seem to be killed out of boredom rather than as prey. I guess the city maybe they would be more desperate than here, where you can’t go 10 feet without stirring something up.

We have a major rat problem here out in the country of West Kingston. They have setup tunnels all around our backyard and throughout our chicken run and underneath the coop. It went from zero to countless really quickly. I am watching closely on the hawks that have been frequent visitors recently. They seem to be leaving our animals alone, and hopefully going after the rising rat population (and the poor bunnies). I guess we need to get serious on eradicating them before coyote or hawks are attracted and decide cat or chicken would be a better meal…

I’m surprised the article doesn’t mention secondary poisoning of birds of prey as one reason for rising rodent populations. Aren’t the same poisons that kill rats and mice also killing the birds that eat them?