Why Orphaned Washington State Cougars are Ending Up in Eastern Zoos

Cougar advocates who have studied mortalities are concerned that hunters may be killing too many females

April 18, 2024

Editor’s Note: ecoRI News is publishing this story as part of a content-sharing partnership with fellow independent, environmental news organization Columbia Insight. Based in Hood River, Ore., Columbia Insight reports on environmental issues affecting the Columbia River basin.

About six months after she and her family moved into an off-the-grid home on 35 acres near Husum, Wash., Kelsha Erickson started losing chickens.

At one point, she lost four birds in less than two weeks.

That put an end to free-ranging for the three remaining chickens. Erickson confined them to a pen she built from fence panels and chicken wire.

“I had accepted the risk to my chickens, and knew I didn’t have a completely secure structure, because having toddlers, there are limitations to what you can get done in a day,” she says. “I thought we were good.”

But one day, while she was in town, her husband called to tell her that bobcats or cougars had killed another chicken.

One of the cats had reached into the pen and decapitated a chicken but was unable to pull its body through the fence.

The culprits turned out to be three hungry cougar kittens that lost their mother before they learned how to hunt wild prey.

Without her, they wouldn’t survive the winter.

But Erickson and wildlife specialists at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife intervened.

Starving orphans

When Erickson got home from town that day, she found two frustrated cougars outside her chicken pen.

She fired a few shotgun shells to scare them off.

Ten minutes later, she heard her dog growling. The cats were back, desperate for a chicken dinner.

Erickson emailed a photo of the cats to a neighbor, who told her they were cougar kittens that looked emaciated.

The next morning, Erickson called the Washington Fish and Wildlife Department’s local wildlife conflict specialist, Todd Jacobsen, to tell him about the three kittens. She had already consulted him earlier when she thought she was losing chickens to a bobcat.

“Within four hours, he was up here,” Erickson says.

Jacobsen set up trail cameras to look for an adult accompanying the kittens but didn’t see one.

“The fact that [the kittens] were out by themselves and showing up during the day at the same residence, that’s not normal cougar family behavior,” he says. “I am certain that they were orphaned.”

It’s not clear how the mother died.

Cougar mothers “don’t just walk away or abandon their young,” says Richard Beausoleil, the state wildlife agency’s cougar and bear specialist. “Something happened.”

Four cougars were killed within the same game management unit as the Ericksons’ home during the month before the kittens were discovered, but there’s no evidence that one of them was the kittens’ mother.

Jacobsen offered Erickson options for dealing with the kittens.

She chose to help him trap the kittens so that one of his colleagues could try to find a new home for them.

Cougar country

A year ago, Erickson, her husband, and their twins — a boy and a girl — were living in Lake Oswego, Ore., a Portland suburb. Erickson saw a real estate listing for a remote, ridge-top property on a logging road in Washington’s Klickitat County and showed it to her husband.

At first it was a joke, but by May 2023 they had bought the house and moved in.

Erickson spent her early childhood in Alaska and is no stranger to rural living. Still, she wasn’t expecting to see so many rattlesnakes near her new home.

With two toddlers, she worries more about the snakes than cougars.

“Seeing cougars at all is a pretty rare occurrence, and it’s even more rare to see cougar kittens,” says Jacobsen.

At Erickson’s house, Jacobsen set up live traps and cameras. He hung meat in the traps.

By morning, two of the kittens were caught.

Jacobsen and a co-worker transferred the two captured animals to kennels.

The kennels had livestock dishes with food for the cats. Erickson used a funnel to give them water.

The next morning, they found the third kitten in a trap and transferred it to a kennel.

Jacobsen and his colleagues fed the animals again, then transported the kennels to Beausoleil in Wenatchee, Wash.

Before they left, Erickson took some photos.

“If you weren’t there hearing them with this low growl and swatting at the door, they do look rather cuddly,” says Erickson. “But they’re not cuddly, not if you want to keep your fingers and your eyes.”

“We’ve been calling them ‘spicy’ kittens,” she says.

Killing of female cougars on the rise

When the kittens reached Beausoleil, Jacobsen chemically immobilized them, examined them, and used tweezers to remove a birdshot pellet from one of the kittens. The shot had come from Erickson’s warning blast, but the injury was superficial.

Beausoleil reported that the kittens were thin but doing OK.

The three animals, two males and one female, all weighed between 21 and 23 pounds.

Beausoleil estimated their age to be about 17 weeks, based on their size and eye coloration. Cougar eyes change from blue to yellow as the animal matures, and cougars typically stay with their mothers until they are about 18 months old.

Two facilities accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums have agreed to take the orphans. Two of the kittens will go to North Carolina, and the third to Pennsylvania.

Washington cougar kittens that have been placed at zoos over the past 20 years have been seen by about 40 million to 50 million people, Beausoleil says. “There’s a lot of nationwide education in that.”

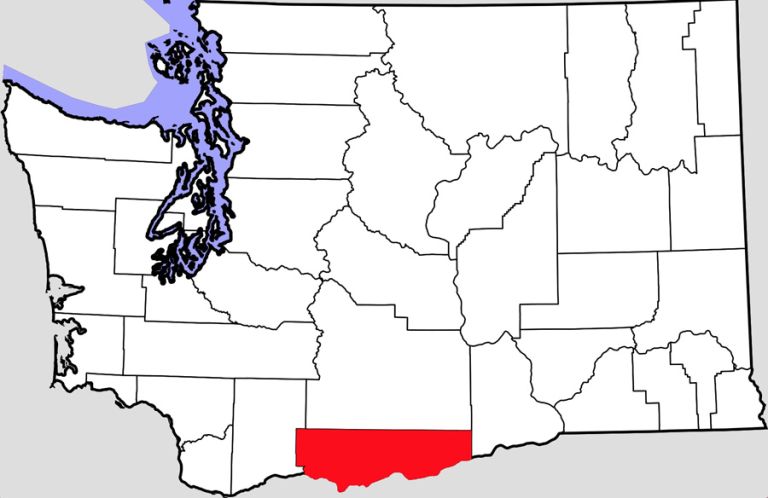

In southwest Washington’s Region 5 — which includes Klickitat, Skamania, Clark, Cowlitz, Wahkiakum and Lewis counties — this is the third litter in 13 months that Jacobsen’s team has rescued.

During his six previous years on the job, there were none.

The first capture happened in October 2022, in the town of Klickitat. A domestic dog had killed one kitten, but its two littermates were rescued and sent to the Houston Zoo.

A second litter was captured in May 2023, after a landowner shot a female cougar while it was killing a sheep. One of the kittens died, but two others survived and ended up at the Philadelphia Zoo.

While these kittens will spend their lives in confinement, young cougar kittens typically starve to death when they lose their mothers. They are also lost to hunting, vehicle collisions, and disease.

Even at seven or eight months, cougars may not be able to survive on their own, says Beausoleil.

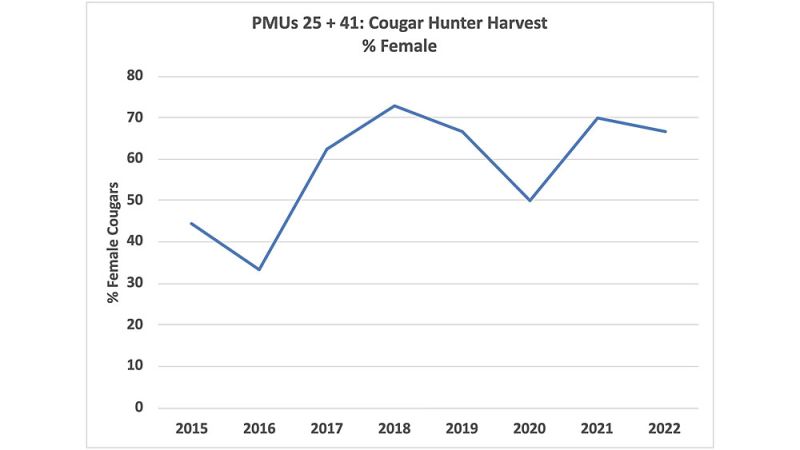

Cougar advocates who have studied mortalities in Washington are concerned that hunters may be killing too many females. In five of the six past years, 62%-73% of hunter harvests reported in the two population management units (PMUs) in Klickitat County and eastern Skamania County have been female.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is assessing the latest cougar population information statewide.

“Locally, there’s no doubt the mortality is higher than we want it,” Beausoleil says.

The continuing removal of cougars by the Klickitat County Sheriff’s Office has contributed to the rise in mortalities in the county.

Cougar spotting

In Washington, it’s unlawful to kill spotted kittens, which usually weigh less than 80 pounds, or adult cougars accompanied by spotted kittens.

However, Jacobsen says “it can be really challenging” for people to tell male and female cougars apart — or even to correctly identify a cougar.

The majority of “cougar” sightings reported to the wildlife agency turn out to be house cats.

Adult females are typically smaller than males, and nursing females tend to have darker fur around their teats, but this marker is difficult to see.

Males have a black penis sheath — a black spot about the size of a quarter located between the legs and a few inches below the anus — that is also difficult to see, because it’s usually covered by the tail when the cougar is moving.

“Seeing cougar kittens by themselves on multiple days is a pretty good indicator that they’re orphans,” Jacobsen says.

He encourages hunters to spend time observing a cougar before shooting. That may enable the hunter to determine whether the cougar is a mother with kittens.

Erickson grew up in a family of hunters and says she wouldn’t be opposed to shooting an adult cougar that’s a persistent threat.

But she’s glad she got the chance to help state wildlife experts “find a better solution for the kittens than starvation or getting killed by hunters.”

She’d like other people experiencing cougar conflicts to know that there are nonlethal alternatives available.

Just ban hunting… Killing beings for sport is simply unethical. It’s a shame it’s still allowed in a “progressive” country.