‘Pokémon in Real Life’: How One App Helps Experts and Amateurs Cast Wider Net Into Natural World

November 20, 2023

Forty years ago, when Karen Beck started identifying the wildlife around her, she clomped around woods and wetlands with a backpack filled with heavy textbooks.

One for butterflies, one for plants, one for soils, and so on, she said.

“Granted, the more you did it, the more you learned,” said Beck, who is a landscape architect by trade. “Hopefully, you could bring fewer and fewer books, but it was always something where you were spending a lot of your time, sitting on the ground somewhere, hopefully not in poison ivy, figuring out what was around you.”

But then, a few years ago, when Beck participated in her first BioBlitz — a 24-hour species-identifying bonanza hosted by the Rhode Island Natural History Survey — she discovered something game-changing: an app called iNaturalist.

“I absolutely fell in love with it,” Beck said. “I thought it was the best thing ever.”

All of a sudden, it didn’t matter very much if she didn’t have the right guidebook in her bag. “To have an app in your hand with your phone that basically identified everything,” she said, “it was mind blowing.”

Beck is now one of many Rhode Island naturalists — amateur, expert, or somewhere in between — using the app to help them explore the world around them and to add to scientific discovery.

iNatualist allows users to catalog species using artificial intelligence and crowdsourcing to identify what organism you are looking at.

A user can upload a photo, audio clip, or gif to the app, which can suggest what it could be based on where and when it was taken and what it looks or sounds like. A poster can use iNaturalist’s suggestions, make their own guess, or leave the observation without an ID.

The post then pops up on a map, unless the user chooses to obscure the observation’s location or it’s a rare species, so that other users can see what was found in a given area and help correct or confirm what it is.

Deana Tempest Thomas, founder of the Rhode Island Mycological Society, said iNaturalist has been especially helpful for the fungi-finding community.

Fungi are an often overlooked biological kingdom, Tempest Thomas said, but having more eyes out in the world looking for the organisms, big and small, is helping expand the community’s knowledge of mushrooms and their brethren.

She particularly likes the map function of iNaturalist, which can show her not just that a fungus has been found in Rhode Island, but how many times and in what types of areas.

Unlike many plants, fungi don’t grow in the same places season to season or year to year, but having a record of where one has been found in the past can help Tempest Thomas share that information with landowners, to show them how they can conserve species.

“Things are disappearing faster than we can get an assessment,” she said, explaining that mycologists are particularly data deficient. But iNaturalist helps them fill those gaps.

The Fungal Diversity Survey, a nonprofit that promotes fungal conservation, recently challenged at-home mycologists to find some species thought to be rare in the Northeast, and report their findings on iNaturalist.

Through the challenge, Thomas Tempest said Rhode Island fungi-finders have been able to show that some species considered rare to the area do exist in the state.

For Thomas Tempest personally, her IDs of a few cordyceps — fungi that grow on insects — have only been possible with help from the wider mycological community through iNaturalist.

“There’s no book for this kind of thing,” she said, adding that that type of fungi is rarely reported. She gave a little fist pump into the air while discussing it, mimicking her reaction to the interesting find.

On top of employing iNaturalist to get a better understanding of the natural world, some academics are using the app in their classrooms and to aid their research.

Providence College professor James Waters, a comparative physiologist whose research often focuses on ants, said she sees iNaturalist as an easily accessible and extensive database, in part because it’s open to everyone, not just experts like her.

Technically, Waters’ 8-year-old could take a break from Minecraft and hop on iNaturalist to help make an identification just like an academic, she said.

“You don’t have to be an expert, you don’t need a Ph.D.,” she said, and in that way, it’s a pretty “democratic” platform.

There is debate about whether that’s a good thing, Waters said, because it can lead to incorrect identifications, “but I don’t think we should ignore what people are recording.”

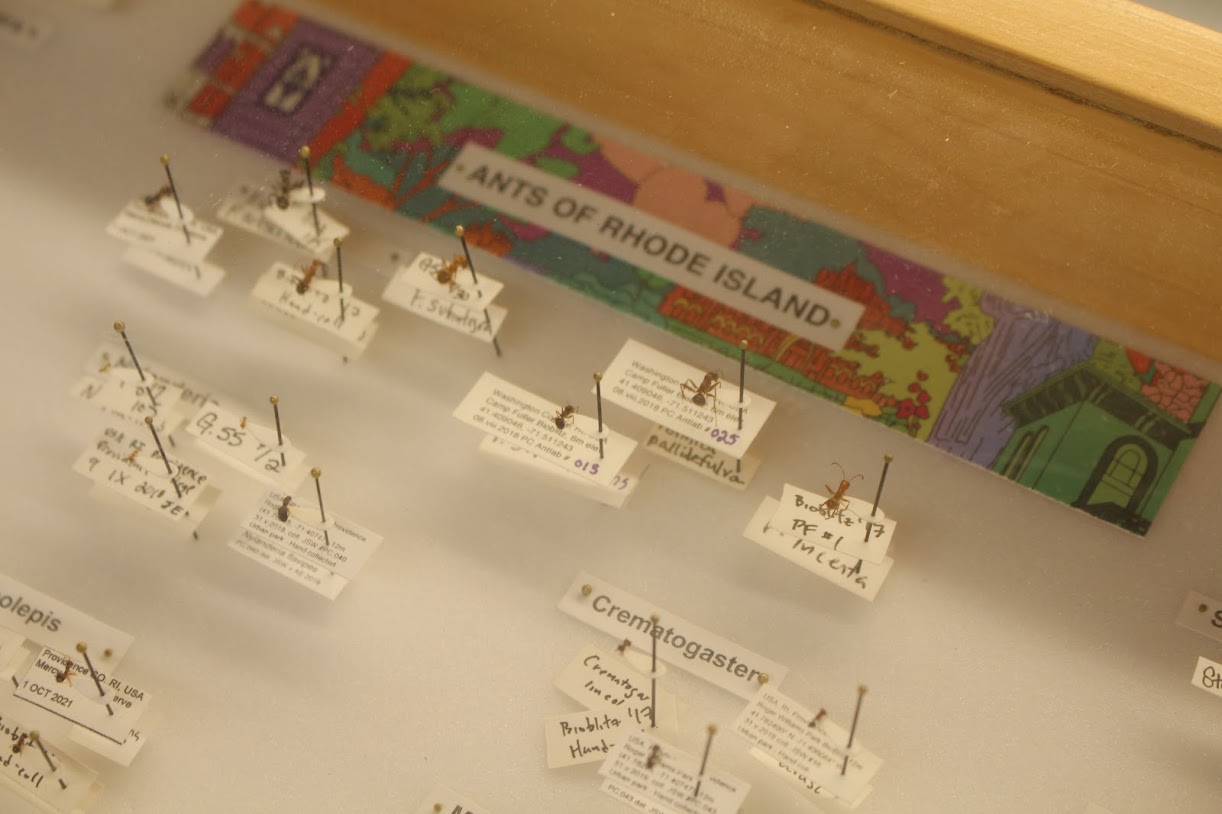

Waters recently used the app to create a survey of ants in Rhode Island, to get a better sense of what species are marching around the Ocean State.

There aren’t many ant experts nearby, so Waters said iNaturalist has been a great way to access other scholars. Some of the app’s users have been able to correct her IDs, which she said she appreciates.

“It’s nice to be able to tap into that wider community,” she said.

Her favorite identification from iNaturalist is the needle ant, an invasive species that Waters and her students found on campus. The identification key for the species in her guidebook wasn’t very good, but by posting the photo of the insect on iNaturalist and pointing some colleagues to it, they were able to figure out what it was — and that it was the first New England sighting of the tiny insect.

There are limiting factors for the app, like the inability to upload full videos (you can upload stills, gifs, and links to videos uploaded elsewhere). Video is actually important for ant identification, Waters said, because how an ant marches can be a big clue to what type it is.

iNaturalist is “one type of evidence that can be used,” Waters said. “It’s one piece.”

Water’s colleague, assistant professor Rachael Bonoan, who works in the lab next door, also uses iNaturalist with her students and her research.

Bonoan is a pollinator ecologist, and at the start of one of her courses, she takes her students on a “pollinator safari.”

The purpose of the exercise is to teach them the basics of field observations. They use butterfly nets and iNaturalist to start learning how to identify life around them.

“A lot of students don’t think we have wildlife on campus,” Bonoan said, “but we have a lot!”

iNaturalist, which is easy to use and requires no extra equipment, gets them engaged.

One of her students said the app is like “Pokémon in real life.” He went on to win both semester-long iNaturalist challenges that Bonoan holds, recording the most observations and most species identified.

The app also gives her students access to experts they likely wouldn’t otherwise interact with.

For a project on Rhode Island’s pollinators, there are a few people on iNaturalist that are the “big names in bee taxology,” Bonoan said, who have helped her researchers and students identify the species they’re observing. “These are the people whose papers we read in class.”

Beck said the collaboration is part of what she also loves about being on iNaturalist.

“It’s citizen scientists who have no background whatsoever, kids, people who have multiple Ph.D.s,” she said. “It’s the whole gamut from one end of the spectrum to the other.”

Beck’s observations have had a research impact. She sent a species specimen to a scientist in Spain, and recently someone from Harvard University reached out about a beetle she had found in her backyard.

“It’s fascinating what people are researching and the fact that you can help them, even not being an expert yourself,” she said. “I think iNaturalist is the bomb.”