Playing Shark Tag Takes Teamwork

March 27, 2024

The shortfin mako shark in the above video is wearing an expensive accessory bought by a South Kingstown-based nonprofit co-founded by a lifelong Rhode Islander.

Jon Dodd, the Atlantic Shark Institute’s executive director, said getting an acoustic tag, or any tag, for that matter, onto a shark works like a “NASCAR pit stop.” A crew of four, sometimes six, has a maximum of 12 minutes to get a tag attached and take a blood sample and measurements. If a sharks begins to look lethargic, Dodd said the animal is immediately placed back in the sea, even if all the data hasn’t been collected or the tag fastened.

A hose is put in the shark’s mouth to flush salt water through its gills, and a towel is often placed over the eyes to keep the animal calm.

The Atlantic Shark Institute, an all-volunteer nonprofit, partners with other shark scientists and researchers, which allows collaboration to play a critical role in the research, management, and conservation of large predatory sharks in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, according to Dodd.

“We have to spend wisely to advance science,” he said. The institute’s budget gets a helping hand from 20 local boat captains who provide their vessels and fuel free of charge for tagging research.

Dodd noted tagging allows researchers and scientists to track where sharks go and when. Shark tagging in southern New England mostly happens from June to September, and the rest of the year is spent analyzing data.

Given the vulnerability of most of the shark species they are tagging, studying, and tracking, Dodd said, they abide by strict protocols regarding the way the sharks are handled when they are being caught, tagged, and measured. He noted that traditional J hooks, which can fatally puncture an organ, have been replaced by circle hooks, which are more likely to lodge in the corner of a shark’s jaw, making removal easier. Fishery regulations also require hooks to be composed of corrodible metals which, unlike stainless steel, degrade faster and increase the chance of a shark’s survival if a hook can’t be removed.

The type of tag used is determined by the species caught and the study being conducted, according to Dodd.

The least expensive are national fisheries tags — an index card in a plastic tube attached to the base of the dorsal fin. These cards are provided by NOAA Fisheries for free. A shark swims around and “if somebody caught it someday, they say please unscrew the cap and the card rolls out and it says please call the National Fishery Service and tell us where you caught this shark, what size it was, et cetera. So pretty cool.”

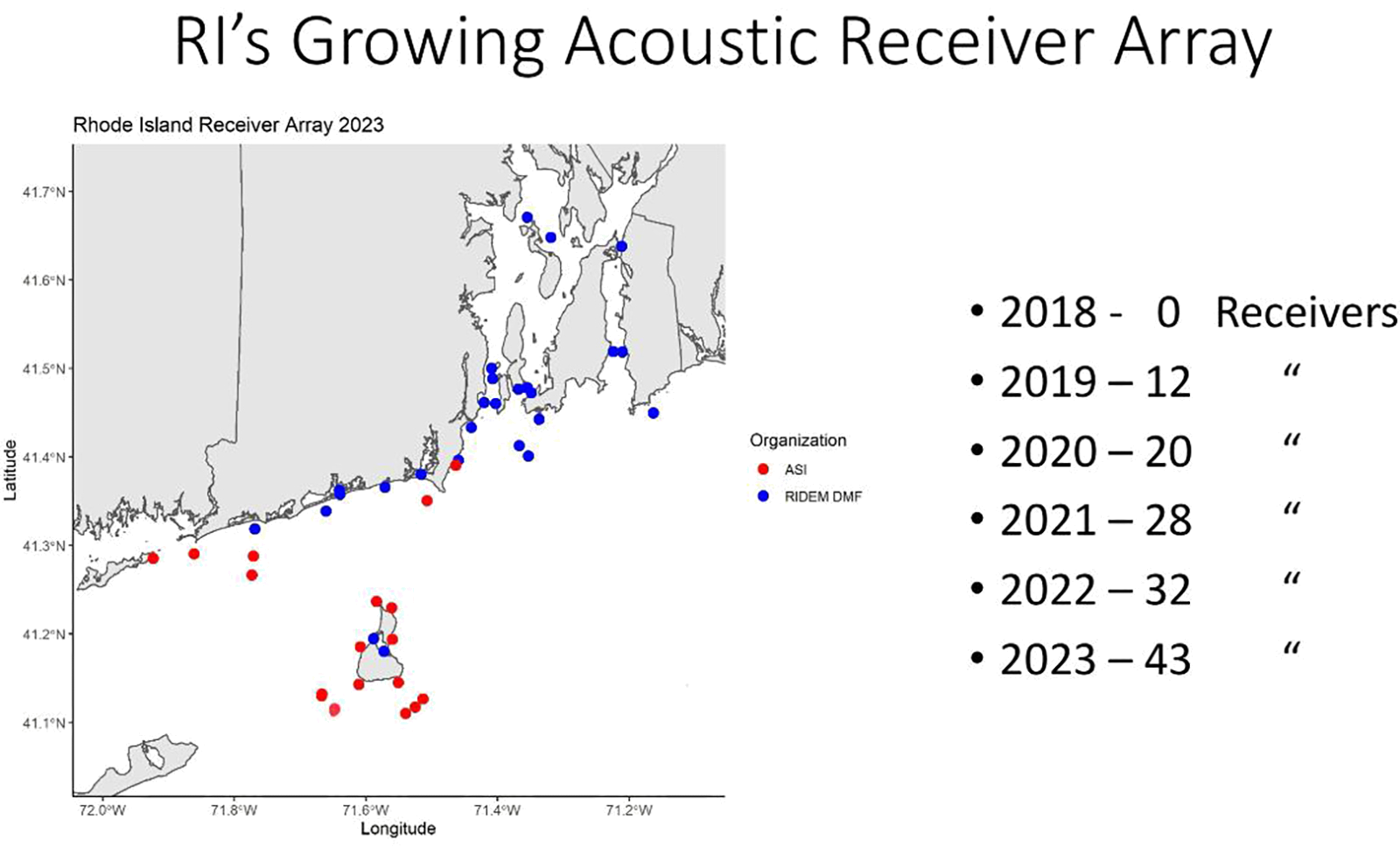

Acoustic tags, which cost $425 and last about a decade, track a shark’s movement via signals picked up by acoustic receivers, which cost $2,500 each, that have been placed up and down the East Coast. Both the Atlantic Shark Institute and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management have placed receivers in local waters.

Pop-up satellite archival tags — each with a price tag of up to $4,000 — provide even more detailed data beyond location, such as water depth and temperature. They last about two years before the battery dies and the tag corrodes and falls off the shark.

This technology, from rolled-up information cards in plastic tubes to satellite receivers, allows researchers to better understand the migratory patterns of different species.

The Atlantic Shark Institute’s geographic focus is the Atlantic Ocean, from Canadian waters to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. It also supports research in Bermuda, the Bahamas, the Caribbean, the Azores, and in the Bay of Fundy.

The institute’s mission, and that of its science partners, is “to do the highest quality shark research to help manage and conserve these magnificent animals.”

Dodd, a La Salle Academy and University of Rhode Island graduate, helped launch the institute in 2018, after a 25-year career running a financial business with one of his brothers. During that time, his passion for shark research never waned.

During a recent conversation with ecoRI News, Dodd often used the words “beautiful” or “awesome” to describe a shark species — well, maybe not spiny dogfish.

Dodd has spent much of the past 45 years, even while working full-time in a totally different field, thinking about, learning about, and studying sharks. He has caught, released, and tagged some 1,000 sharks for various research projects during the past four-plus decades.

The Providence native graduated URI with a degree in biology with a fisheries focus. But his passion for sharks began when he was a young teenager and came across a blue shark while boating locally.

“When I saw my first shark, I was fascinated, and it just kept rolling,” Dodd said. “But it quickly went from fascination to concern. It was just this realization that man will take a lot of things out of an ecosystem, and it didn’t feel right.”

His concern about the species grew during the 1980s and ’90s, especially as he watched the popularity of shark tournaments grow, the number massacred for their fins increase, and the amount killed in bycatch rise.

“We take over 100 million out of the ocean every year. It’s just too many,” said the 62-year-old Dodd. “And the big problem is that a lot of these sharks are very slow growing and slow maturing. I’ll give you a perfect example. Everybody loves the white shark because it’s so iconic, but it takes the female great white 33 years before she’s sexually mature. So we’re talking right now and it’s March 21, 2024, so if a white shark is born while we’re chatting that shark will finally reproduce when I’m 95 years old.

“For the first time she can finally replace herself, but what’s the chance that her pup [litter sizes range from 4-12 individuals] survives? A lot of things can eat you, you can bite the wrong hook, you can sit on a longline and die because you’ll basically suffocate. You can get dragged up somewhere. You can get caught by a recreational guy that poses with it too long and kills it. What’s the chance that you survived 33 years so you can reproduce?”

By tagging as many sharks as they can, Dodd and his respected team of partners hope their research provides a clearer picture of the types of sharks that swim off the southern New England coast, their health, and behavior.

Dodd said that as ocean temperatures rise, the range and type of sharks in New England waters is changing. He noted data from the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer indicates the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 99% of the world’s oceans. He said New England has the fastest increasing ocean temperatures in the country, up 3 degrees in the past century-plus. These warming waters are leading some sharks further north and bringing in warm-water sharks from the Caribbean.

Among the warm-water sharks Dodd and his team are now catching and tagging are blacktips and spinners.

Besides those two sharks, the institute also monitors the common thresher, porbeagle, shortfin mako, and white, and is juggling about a dozen research projects, including seasonal movements of great whites in Rhode Island and shark-population density off Block Island.

The United States boasts one of the best-managed and sustainable shark fisheries in the world, Dodd said, but it is still witnessing declining shark numbers. He noted that an appearance of sharks in a certain area doesn’t mean their populations are healthy worldwide.

For many species, harvests aren’t sustainable and an alarming number of species are considered vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered as a result, according to Dodd. He noted sharks are critical to ocean health in a variety of ways. He said humans can’t continue to kill some 100 million sharks every year and not create (or expect) long-term impacts to the health and well-being of the marine ecosystem.

Since 1975 the world’s shark populations have declined by 71%, according to the Save Our Seas Foundation. It’s a disturbing trend that Dodd said has major implications beyond the marine environment.

He likes to tell people, “Shark health is ocean health and ocean health is our health.”

“Sharks are the apex predator, and they regulate everything underneath them,” Dodd said.

He noted an absence of sharks can enable second-tier predators and/or prey species to grow unchecked, creating a cascading impact on the oceanic food web that can limit biodiversity and degrade an entire marine ecosystem, such as a coral reef.

A similar degradation of ecosystems happens on land when humans remove wolves.

Federal protections that prohibit the killing of some shark species, including great whites and shortfin makos, have helped their populations somewhat stabilize. But most sharks are highly migratory and aren’t protected worldwide.

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsRecent Comments

Leave a Reply

Your support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings

Great article Frank and very well done. We appreciate all you do to bring attention to environmental issues facing our region and the nation. Keep up the excellent work!