It Is An Insect World and Humans Are Just Living In It

Rhode Island catches buzz about protecting pollinators

February 1, 2024

For much of the year, except now, if Rachael Bonoan isn’t in a classroom or in her office, there’s a good chance the assistant professor of biology at Providence College is roaming the 150-acre campus searching for bugs. Pollinators to be precise.

Since 2020, Bonoan and her students have identified 110 insect pollinators on campus, feeding on 30 species of flowering plants.

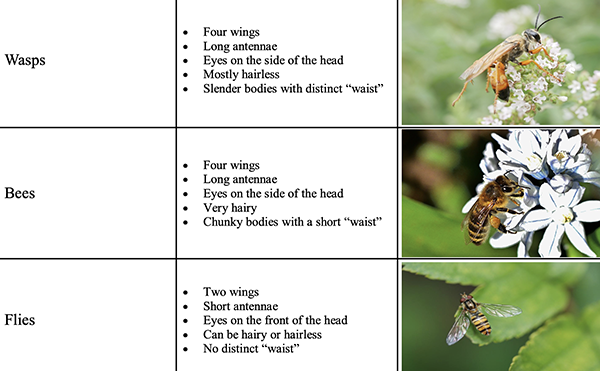

“Mostly bees, because that’s our main focus, but we also have butterflies, wasps, and some flower-visiting flies,” Bonoan said. “I would say the flies are the hardest for us to learn to identify just because they’re quick and small. We’ve got some really big beautiful wasps that are just really easy to identify in the field.”

Besides catching and observing insects, the researchers also study which plants might be best for pollinators.

As an undergraduate student, she was studying birds, but her career path took an unexpected turn.

“I had the opportunity to do a summer research project studying butterflies, and I realized, ‘Wow, I can get paid to chase insects around with a net.’ This is kind of what I grew up doing,” Bonoan said. “I’ve always loved insects.”

We all should, because without them, none of us would be here.

Pollinators, especially bees, and not just honeybees, play a significant role in maintaining the function and diversity of ecosystems through their unique relationship with native flowering plants.

Pollinators account for the fertilization of some 35% of crop production worldwide. Crop pollination services are worth up to $530 billion annually. Basically, wild pollinators feed us for free.

Of all flowering plants, nearly 90% require an animal — mostly insects, but also vertebrates such as birds and bats — to transfer pollen from one flower to another, allowing the plant to produce seeds and fruits.

Most pollinators, however, are insects, most notably bees, butterflies, flower flies, wasps, and moths. Bumblebees, for one, are important pollinators that visit a variety of native plants. Rhode Island has historically been home to about 12 bumblebee species.

Bonoan noted insect pollinators get most of their nutrients from flowers — pollen provides protein and fats, nectar provides carbohydrates, and both provide trace amounts of vitamins and minerals.

But many wild pollinators are declining in abundance, diversity, and geographic distribution. Their increasing loss creates accumulating risk.

The persistent assault on native pollination systems — by intensive agriculture, the overuse of pesticides, development, the burning of fossil fuels, and a proliferation of lawns — poses a significant threat to human and ecosystem health.

Certain pollinators, such as the rusty patched bumblebee, are heading toward extinction. Some 50 butterfly species in New England are in decline, according to Robert Gegear, assistant professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and founder of the Beecology Project.

Surveys of Rhode Island’s bumblebee and eastern carpenter bee populations, conducted from 2014 to 2021 by Howard Ginsberg and Steven Alm’s research groups at the University of Rhode Island, found that nearly half of these species may have disappeared from the state.

Total insect mass worldwide is decreasing by 2.5% annually, according to a 2019 study. About 40% of insect species are declining and a third are endangered, with butterflies and moths among the worst hit.

While land-use management, lawn-care chemicals, habitat loss, the climate crisis, and other factors play a prominent role, Bonoan is studying an often neglected part of the puzzle: Whether insect pollinators are getting a well-rounded diet.

“If they’re healthier, they’re going to be able to deal with whatever environmental stressor better,” Bonoan said.

She explained that if, like humans, insect pollinators are eating a balanced diet, they are likely healthier and better equipped to deal with change. Industrial fields of monoculture and carpets of lawn provide nothing more than a human diet high in corn syrup and processed foods.

Bonoan noted lawns are “food deserts” for pollinators.

“Lawns are really bad for pollinators and are really bad for the environment in general,” she said.

She spoke about trees as an overlooked but important source of pollinator food.

“We tend to forget that trees flower too, right? We think of gardens, and we forget about trees,” Bonoan said. “But those are some of the earliest spring resources. There are a lot of bees that really rely on those trees.”

Insect pollinators play vital role

As the late biologist and naturalist Edward O. Wilson once said about these vital invertebrates: “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.”

To better protect these priceless creatures requires information that allows for the development of effective conservation and restoration strategies. How to recreate landscapes, destroyed by relentless building and poisoned by chemicals, that truly support pollinator biodiversity is a complex issue.

To that end, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and its partners, including PC’s Bonoan and URI’s Alm, a few years ago launched an initiative called the Rhode Island Pollinator Atlas. The effort, at least at this moment, is solely focused on bees — data are still being collected for both the Rhode Island Bumblebee Survey and the Rhode Island Wild Bee Survey.

The effort to inventory the state’s bee species — and, in the future, perhaps all pollinating insects — is significant and designed to inform future conservation plans that protect native pollinators.

There are an estimated 250 species of bee in Rhode Island, but the state’s collection of bees, unlike its birds, has never been comprehensively surveyed.

DEM officials said conducting an inventory of Rhode Island’s bees will help determine which species need help and which plants and habitats are most important for their survival. The work will also be used to assess human and environmental threats.

Funding for the initiative comes from several sources: federal and state grants for species of greatest conservation need and habitat protection; the Washington, D.C.-based Wildlife Management Institute, which pays for the salary of contract biologists; and the work of volunteers.

The project’s current supervisor, DEM biologist David Kalb, noted native solitary bees are of particular concern.

“When most people think of a bee, they think of a honeybee, which is actually not even a native bee,” Kalb said. “There’s a whole host of other native bee species that are also really important. … They have symbiotic relationships with their host plants. They rely on their host plants just as much as some of their host plants rely on them.”

These countless, intertwined relationships support biodiversity.

Jen Brooks, DEM’s volunteer program coordinator, noted that if people stopped planting nonnative vegetation and went native, that would go a long way in supporting pollinator health.

“We always say messy is best for bees,” she said. “Leave the leaves and hallowed stem-type plants because they serve as nesting materials … providing a messy, more natural area for bees is really helpful.”

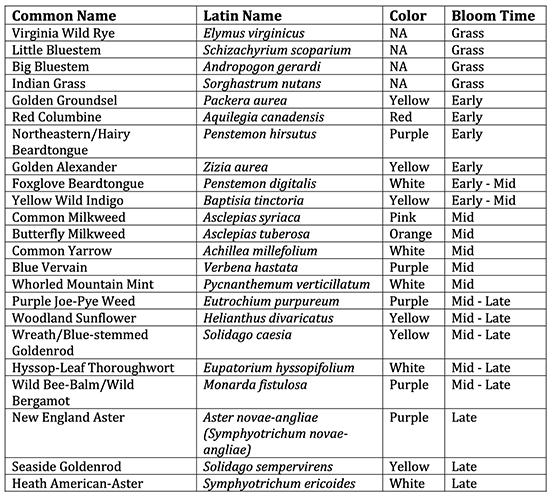

The preference of pollinators varies by species, but, in general, native insects prefer native plants. That relationship, though, is much more complicated than that simple premise. It can take a variety of plants to support one pollinator species, as many insects require a host plant plus sources for nectar and pollen. Those three needs aren’t typically provided by a single plant species.

Native bees, for instance, have vastly different flower preferences than honeybees, which were brought over from Europe. Short-tongued bees are attracted to cup-shaped flowers, while long-tongued bees prefer tubular ones. The preference of medium-tongued bees falls somewhere in between. Many lawn-covered residential and commercial landscapes lack flowers, especially tubular ones.

Wasps visit flowering plants regularly to feed on nectar and, in some cases, to eat and gather pollen from flowers. Wasps tend to specialize on small, shallow flowers with concentrated nectar — lots of sugar — because, unlike bees, they have short mouthparts. They are efficient pollinators of some milkweed and orchid species. About a dozen wasp species can be found in Rhode Island.

Flower flies, also known as syrphids or hoverflies, are an important but underappreciated insect pollinator group. There are more than 6,000 species of flower flies worldwide and 850 species in North America. They regularly visit flowers to forage for nectar and pollen, to rest, or to look for mates. When they visit, pollen gets stuck to their hairs, which allows them to carry out the ecosystem service of pollination. Eight species of flower flies are common in Rhode Island.

But as pollinator species once common in southern New England fade, such as the yellow-banded bumblebee, the yellow bumblebee, the half-black bumblebee, and the aforementioned rusty patched bumblebee, the impact doesn’t end with their disappearance. The plants they bonded with over centuries are also impacted, and so are we.

The part of the pollinator biodiversity decline that goes largely unnoticed is the impact on ecosystem services. Interactions between native species, which have co-evolved for millenniums, support the sequestration of carbon, soil decomposition, and water purification. Their significance goes way beyond food production.

Humans can’t replicate these services and systems.

The experts ecoRI News spoke with for this story offered some tips for supporting pollinators and helping ourselves:

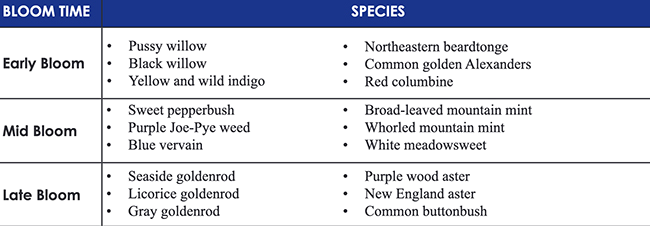

Select nectar and pollen plants so there are blooms in every season — March-May, June-July, and August-September.

Spring floral resources, and trees, are important for at-risk pollinators.

The species of a plant is typically far more beneficial to pollinators than named cultivars.

Select plants that target as many species of pollinators as possible, as a good habitat will support species at risk over the entire season.

Don’t use weedkillers and insect poisons, as they can limit the availability of flowers available for insect pollinators to feed on and/or can poison the nectar and pollen they collect.

Mulch with compost or leaves instead of wood chips to make the ground more accessible for ground-nesting bees.

Allow flowers such as clover and dandelions to grow in your lawn, by mowing less and not as short.

Refrain from clearing leaf litter and cutting old plant stalks, as insects lay their eggs in these and use them for overwintering shelter.

Leave dead trees on your property, as many pollinators use decaying trees to lay their eggs and pupate into adults.

Create gardens. Native, community, rain/retention, windowsill, and rooftop.

To be a Rhode Island Bumblebee Survey volunteer, click here. To be a Rhode Island Wild Bee Survey volunteer, click here. To view Rachael Bonoan’s research on insect pollinators, click here.

We need insects, and the insects do more good for our communities than anything that comes from the State House

An excellent article.

Some months ago I wrote a short article on how to read plant labels to find straight species versus hybrids and cultivars: https://eastgreenwichnews.com/the-power-of-the-plant-label/

Regarding flower flies, as the article states, there are about 8 species that are “common,” meaning they’re easy to catch on mid-to-late summer flowers, but iNaturalist lists over 40 species as having been found in the state, and a perusal of the “Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America” indicates well over a hundred additional species might be present in Rode Island. Under the auspices of the RI Natural History Survey, for which I work part time, I’ll be in the field this summer (and beyond) working to develop a checklist of flower fly species for the state.

Yes, we do need insects like lady bugs, the Six-spotted Tiger beetle, the Locust borer, the Ant lion, Cuckoo wasp, the Pale green Assassin, Dogbane Leaf beetle, Crane flies, Spine Assassin, the American Carrion beetle, Fireflies, et cetera and yet all that is written it seems is the subject of saving POLLINATORS and not other invertebrate species on RIDEM’S 2015 WAP list of wildlife Needing the Greatest Conservationhttps://dem.ri.gov/programs/bnatres/fishwild/swap/sgcnsci.pdf like the Bombardier beetle, Tumble bug and Goldsmith beetle, etc.. Meanwhile I have been photographing native bumble bees for more than 5 years for the Beecology Project including a nest site in my yard. Having said this, I like to add Leaving the Leaves speaks of the need for hibernation of not only native bees but other wildlife too. But Uprooted tree roots make great homes for Solitary Bees and more habitats locations can be found in https://xerces.org/sites/default/files/publications/18-014.pdf. Snags in trees are also are great nesting sites for many wildlife species too! Lastly, Bug boxes if not maintained and properly located do more harm than good!!!