Fear Factor: Hollywood Produced ‘Creature Features’ Left Us Unsympathetic to Plight of Sharks

Half a century later our murderous rampage at sea rages on

March 27, 2024

We’re easily triggered, deathly afraid of things we needn’t be, and apathetic to the dangers we create. It’s a deadly combination.

We are actually the beasts, the monsters, the things that go bump in the night. We’re the mindless killing machines. We just project our savagery onto the animal kingdom.

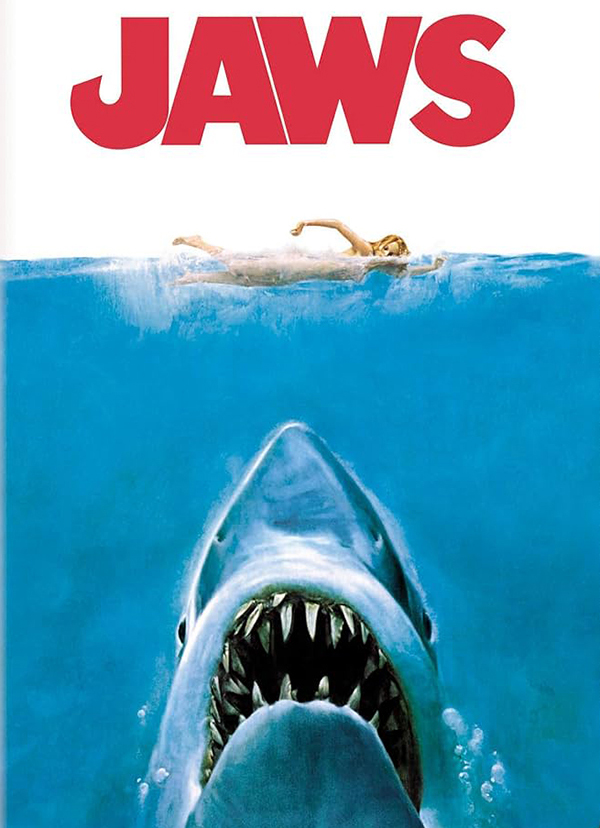

And the summer of 1975 showed the natural world how easy it is to get our hackles up. All it took was a 25-foot-long make-believe shark. The mechanical beast created for our entertainment altered the lives of sharks, and not for the better. The blockbuster “Jaws” — the 2-hour movie is based on Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel of the same name — forever changed how humans perceive these awesome creatures.

The movie is great. In fact, it’s the only one I can remember going to with my late father. We played a lot of sports together, mostly baseball and soccer, and watched a lot of sports together, mostly hockey and basketball, but movie-going wasn’t a Carini thing.

Anyway, I left the theater that afternoon wanting to be a marine biologist. Many others left with a different urge. The famous tagline from the 1978 sequel — “Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water …” — didn’t improve human-shark relations. Overnight, people became afraid. A great white sighting caused an instant panic. It still does.

The movie (and its four spinoffs) led to vendetta and revenge killings of great white sharks. Shark fishing tournaments became all the rage.

During the past 50 years numerous researchers have documented how the movie, which I admittedly enjoyed, has transformed the plight of sharks. It makes me sick to my stomach, as sharks are in my wild kingdom triumvirate along with wolves and donkeys. (Yes, I realize donkeys are a wild stretch.)

University of Sydney professor Chris Pepin-Neff, in 2015, coined the term the Jaws Effect to describe the enormous, detrimental impact the movie had on the public’s opinion of sharks.

He wrote that the “storylines from Jaws underpin the lasting strength of the Jaws Effect: the attribution of intentionality to the shark; the perception that human-shark interactions lead to fatal outcomes; and the belief that the shark must be killed to end the threat.”

Pepin-Neff noted negative perceptions of sharks predate films. At issue, he wrote, is the way in which fictional conceptions have implications for public perceptions and policy responses.

“Jaws” is one of the most recognizable movies in the “creature feature” genre, right up there with “Godzilla” (my personal favorite). This genre portrays animals as villains. These movies are popular, but their impact on the human psyche can be profound, according to a study published in August in the Journal of Environmental Media.

“Through analysing the biography, film poster and trailer on the IMDb database, it was found that sharks were the most depicted species in creature feature films,” according to the U.K.-based study.

A 2021 study found 96% of the 109 creature feature movies analyzed depicted shark interactions with humans as threatening. It’s no surprise then that humans have become inordinately and irrationally scared of sharks. They are presented as relentless killers of humans.

But shark incidents are rare. You are 7 times more likely to be hit by lightning than be bitten by a shark. The chance you are killed by a shark is 1 in 3.75 million. The study’s authors noted that in South Australia’s waters, a known shark hot spot, shark incidents have averaged just one a year for the past 20. Globally, fatal shark attacks number 5-15 annually. On average, there are 63 unprovoked shark incidents each year.

Last year the Florida Museum of Natural History’s International Shark Attack File investigated 120 alleged shark-human interactions worldwide. It confirmed 69 unprovoked shark bites on humans and 22 provoked bites. Of those attacks, 14 were fatal, 10 of which were unprovoked.

On the opposite end of the kill spectrum, humans massacre between 80 million and 100 million sharks annually for sport and food — about 25 million, some 30%, of which are threatened species, according to a study published in January. One in three shark species is threatened with extinction.

Many of these magnificent animals are killed not for food but for a trophy picture or to be stuffed and displayed. Sickening.

Sharks targeted for shark fin soup aren’t taken whole; their fins are sliced off and living mutilated sharks are tossed back into the sea to sink and slowly die. Barbaric.

“Jaws” director Steven Spielberg has spoken about the horrible impact the movie has had on shark populations. In 2022, he told BBC Radio, “I truly, and to this day, regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film.”

“That’s one of the things I still fear — not to get eaten by a shark, but that sharks are somehow mad at me for the feeding frenzy of crazy sport fishermen that happened after 1975,” he said.

Since the movie was released, shark populations have declined by 71%, according to the Save Our Seas Foundation.

The problem of labeling sharks as villains, an animal to be afraid of, hasn’t been limited to film, though. For years the media relentlessly portrayed sharks as scary.

While the media’s hysterical coverage of shark incidents began to change around 2018, according to a 2022 study by Pepin-Neff, much of the damage had already been ingrained.

Humanity’s manufactured fear of sharks and the overfishing of these top predators has put them and the marine ecosystems they support at risk.

Of the 500 or so shark species, 15 are currently listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and another six are threatened, according to NOAA Fisheries.

The most recent global assessment of the class Chondrichthyes — cartilaginous fish, the group of animals to which sharks belong — showed that more than one-third of sharks, rays, and chimaeras are threatened with extinction. Of the 1,199 species assessed, 121 are classed as endangered, 90 as critically endangered, and 180 as vulnerable, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Among those that are the most vulnerable are the shortfin mako, scalloped hammerheads, and the oceanic whitetip.

“With our oceans severely degraded, restoring sharks is key to improving the resilience of these water bodies to climate change,” according to the World Wildlife Fund. “While sharks’ diverse range of species adds complexity to our conservation efforts, the dwindling numbers of these amazing creatures from overfishing and demand for their fins and meat increases the urgency of the task.”

With fossil records dating back some 400 million years, sharks have outlived the dinosaurs and many other forms of life, including us, on this warming planet. I hope we don’t want to be the species responsible for their demise.

Note: I’m not sure what happened to my marine biologist dream.

Frank Carini can be reached at [email protected]. His opinions don’t reflect those of ecoRI News.

Thanks Frank. If we want to get rid of big scary killers, get rid of cars. sharks kill 2 or 3 Americans a year, cars kill thousands. Or maybe just do away with drivers.

yikes Frank, I appreciate how you, and other valiant individuals and groups, are trying to protect nature, but it is getting so discouraging to read yet another report of humanity’s war on wildlife – species of sharks, polar bears, monarch butterflies, bees, elephants, whales, manatees, giraffes, whales, fireflies, amphibians and so many more that I’ve been hearing about all under threat. But besides a core group, hardly anyone seems to care – not just wildlife but the environment, even climate, seems not a factor in our national election. The environment movement has not succeeded in influencing politics at that level. It is difficult enough to make progress with the Biden administration that is at least trying to some extent, but another Trump regime with its disdain for the Endangered Species Act, undermining National Wildlife Refuges, celebration of trophy hunting, drill-baby-drill attitudes, opposition to birth control and reproductive freedom even in the face of continuing rapid population growth, and hostility to climate science – all that would be a death sentence for so much wildlife, but none of that seems to register with the electorate. We need to discuss how to do better

frank

a small bright light with no statistical significance with respect to this situation is that short fin mako fishing was Federally banned three years ago. prior to that we all chased short finned makos as they were delicious and very difficult to land due to their propensity to jump straight out of the water, shake their head and spit the hook. the size limit was 53″ which was about a 125# fish. prior to the ban i noticed and got sick of hooking very immature sized makos so i stopped fishing them long before the ban. in the past years people still shark fish for sport. blue sharks being the most caught. they re all released and tagged if possible as they are totally inedible. there have been days when i ve had four around the boat at once anywhere from six to ten feet each. in the meantime the SFMs have been showing up more regularly (bait fishing for tuna) with some exceptionally sized beasts. a male sfm has to be about 10′ long before it reaches sexual maturity which is a 400# fish. it takes many years to get that big. i don t know about the rest of the world but our local shark population seems to be rebounding slowly. bty one of my tagged blue sharks was caught off Long Island NY retagged and released.

Many years ago i had a 2000# tiger shark (15-20′) scare the s..t out of us 15 miles south of Block Island. she ate all the baits, broke all the lines and sashayed off into the distance