Car Culture Drives Rhode Island’s Climate Inaction

Other modes of transit and those who rely on them are largely ignored, at the expense of everyone

June 6, 2022

The roar of oversized pickups has failed to muffle the hysteria over the rise in gasoline prices.

These two circumstances — the fact they are connected is mostly ignored, as is the fact the cost of gasoline is still far more expensive in most of the rest of the world — perfectly exemplify America’s collective disregard of climate change and the populations most impacted by its consequences. It also highlights the depth of U.S. fossil fuel addiction and how far we will go to insulate the multinational corporations that extract it, even as they continue to report huge profits.

In Rhode Island, elected officials looking to score political points have called for the suspension of the state’s gas tax. Rhode Island currently taxes gasoline and diesel at 34 cents a gallon. The Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) is funded in large part by revenue generated by the state’s gas tax. The tax also helps fund the transportation infrastructure, including the filling of potholes, on which motorists rely.

In response to the two House bills (H7983 and H8006) looking to impose a moratorium on the fuel tax, RI Transit Riders, a grassroots advocacy group dedicated to improving mass transit, has noted the best solution to high gas prices is not to increase demand for gasoline by making driving cheaper, but to encourage alternatives to gasoline consumption by promoting, supporting, and funding public transit, walking and bicycling infrastructure, and electric vehicles.

The federal tax on gasoline, which also funds transportation infrastructure maintenance and repair, is 18.4 cents a gallon and 24.4 cents a gallon for diesel. The rate of the federal gasoline excise tax has been increased 10 times since 1933, when it was $0.01 a gallon, but it has not been touched since 1993, when it went from 14.1 cents to its current rate.

Many of the same Rhode Island politicians in favor of suspending the gas tax have also spent the past several years attempting to eliminate the motor vehicle excise tax. If boats are any indication, Rhode Island lawmakers could one day target the elimination of the state sales tax on cars.

The Ocean State’s no-sales-tax policy on boats went into effect in 1993, thanks in large part to the lobbying efforts of the Rhode Island Marine Trades Association. There is also no boat excise tax in Rhode Island.

And, as a Newport-based yacht seller notes on its website, “you don’t have to live in Rhode Island to take advantage of these exemptions. According to the most recent statistics, approximately half of the registered boaters in Rhode Island live in other states.”

But when it comes to other transportation choices that would benefit Rhode Island’s low-income and non-car-owning (and non-boat-owning) populations, the political desire for action falls off a cliff.

Rhode Island lawmakers for the most part are against proposals looking to make riding RIPTA free. Bicycle sales are taxed (an amendment to Rhode Island law to exempt bicycles from the state sales tax was introduced in January; it was held for further study). Most politicians offer few if any ideas on how to improve public transit on which much of the state’s most-vulnerable and marginalized populations, such as the poor, people with disabilities, and the elderly, rely.

RIPTA leadership can even present itself as uninterested in the needs of the state’s most disenfranchised. Just before summer beach season was to begin, RIPTA announced, without soliciting public feedback, that it was going to discontinue express beach buses.

“It is unfair to require those who cannot afford a car to lose the direct, rapid access to the beaches that the express buses provide,” said Patricia Raub of RI Transit Riders. “Furthermore, given the state’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions, the cost of gas, and the lack and expense of parking at the beaches, it is counterintuitive to make it harder for those who might prefer to leave their cars home to do so.”

After pushback from RI Transit Riders and other advocates, the governor directed RIPTA to reverse course.

The same politicians concerned about rising gasoline prices don’t seem to share the same worry about the rising cost of life-saving medicines such as insulin. The cost of medicine and health care in general have risen faster than gas prices, which places enormous pressure on low-income families — much more so than an increase in the cost of gasoline, the burning of which helps keep this negative feedback loop spinning.

“The over-reliance on fossil fuel-powered, individually driven cars is unsustainable, so much so we passed a landmark piece of legislation just last year called the Act on Climate,” Teresa Tanzi, D-South Kingstown, said during a late-April House Finance Committee hearing. “We are legally required to reduce our carbon output in the rapidly approaching years. In order to do so, we will need to heavily invest and rapidly to make that happen.”

She noted Rhode Island has two “amazing” plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The fully vetted plans were adopted nearly two years ago, but no funding has been made available.

Profit over planet

ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, and BP have earned some $75 billion in profits during the past year, according to a recent report from Accountable.US, a nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based watchdog organization.

A report released in early April by a trio of organizations — BailoutWatch, Public Citizen, and Friends of the Earth — explains how fossil fuel behemoths and their wealthy shareholders have profited off global tragedy — the coronavirus pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the worsening climate crisis — during the past few years.

The 15-page report notes that these powerful corporations have spent $45.6 billion in stock buybacks since the start of 2021.

“This is a master class in war profiteering,” Lukas Ross, climate and energy program manager at Friends of the Earth, told The Real News Network in April. “Oil and gas companies are feeding off humanitarian disaster and consumer suffering in order to reward Wall Street.”

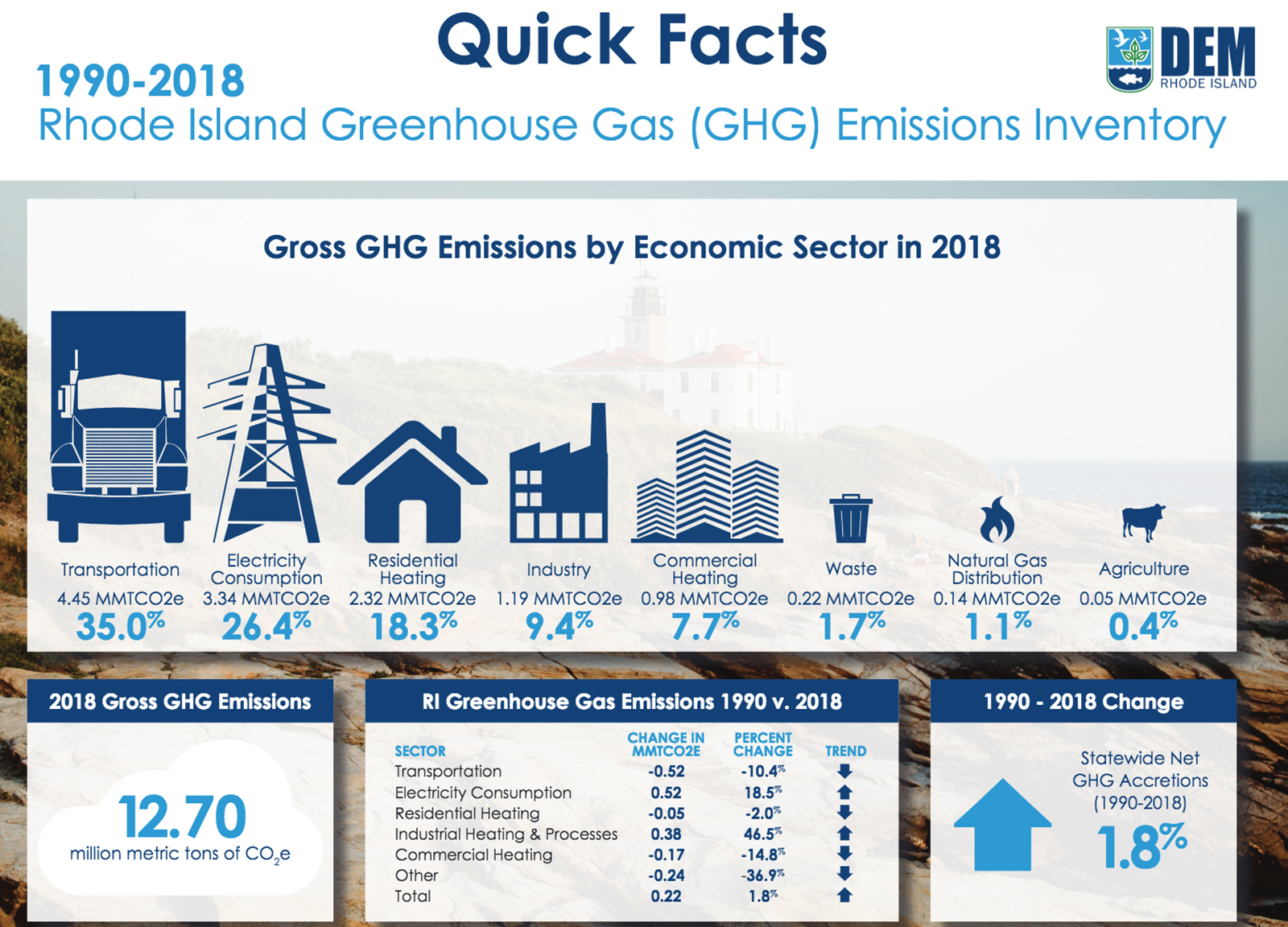

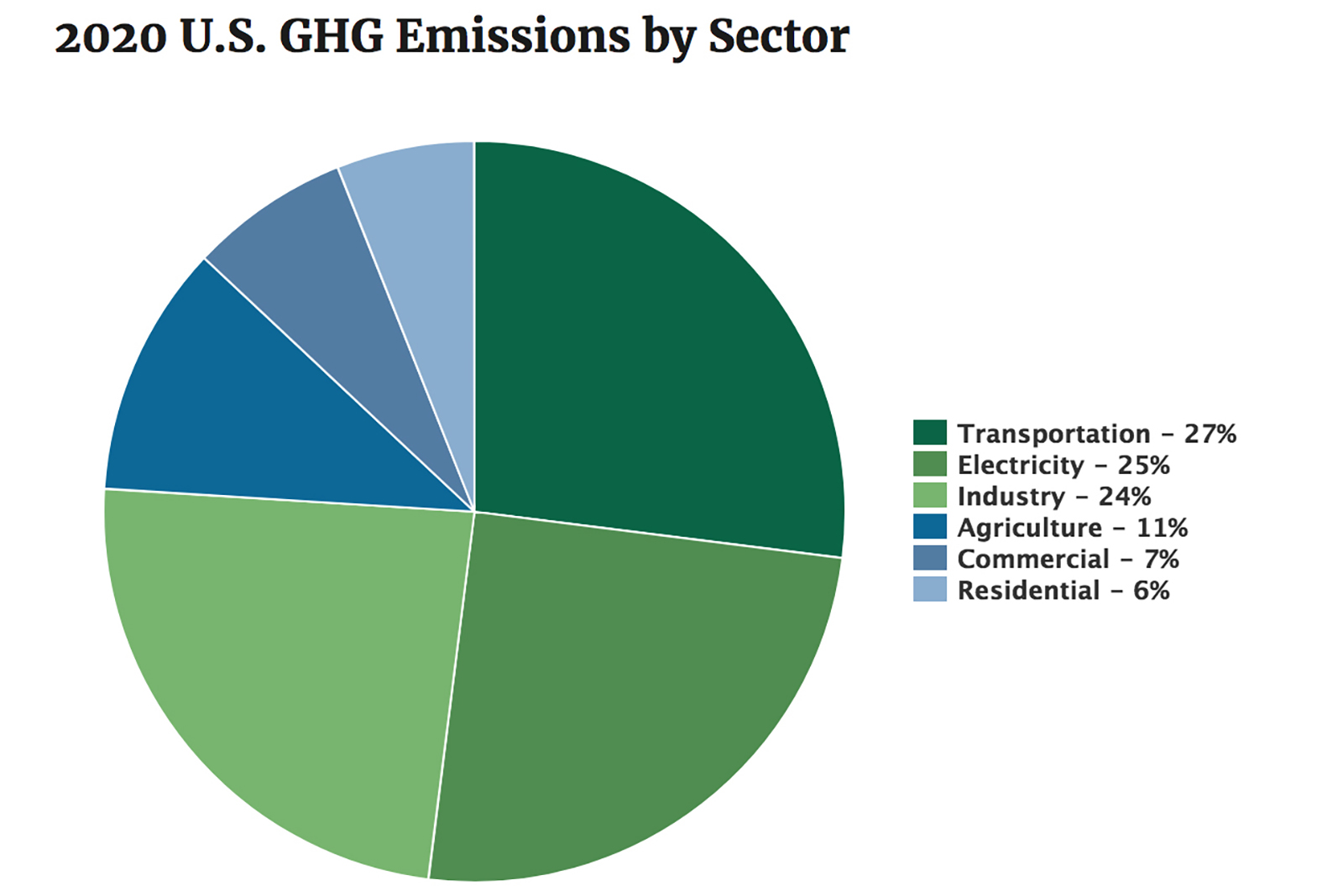

The transportation sector accounts for 35% of Rhode Island’s greenhouse gas emissions — nearly 10% higher than the next highest emitter, electricity consumption. At 27%, the U.S. transportation sector generates the largest share of climate emissions.

Despite the immense amount of climate pollution the transportation sector produces, the U.S. Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy says internal combustion engines “provide outstanding driveability and durability.” The U.S. Department of Energy office also refers to natural gas (methane) and propane as renewable or alternative fuels.

Rhode Island has no plan to reduce emissions from its transportation sector, despite the fact Act on Climate mandates are nearly impossible to meet without doing so. The 2021 law includes a provision enabling lawsuits to be filed when citizens or organizations believe the state is not upholding its climate responsibilities.

To lessen pollution impacts from the transportation sector, the state decided two decades ago it was going to crack down on diesel emissions spewing from Rhode Island’s largest vehicles. It is still trying to figure out how.

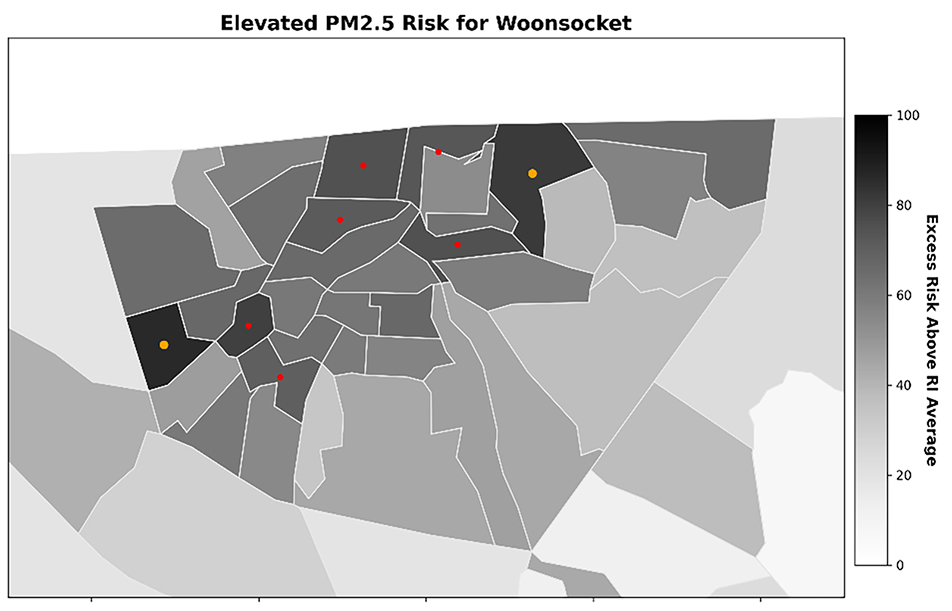

A 2000 amendment to state law acknowledged that heavy-duty diesel vehicles contribute significantly to air pollution and diminish “the quality of life and health of our citizens.”

The amendment also noted the “Citizens of Rhode Island frequently raise concerns about emissions from heavy-duty diesel engines” and “Technology exists to determine the level of exhaust emissions from heavy-duty vehicles.”

“It is in the public interest to establish a program regulating exhaust emissions from heavy-duty diesel trucks and buses traveling within Rhode Island,” the amended law stated. It directed the Division of Motor Vehicles and the Department of Environmental Management (DEM) to tackle the issue and launch such a program by 2003.

Nineteen years later, no program exists.

Last year, Laurie Grandchamp, administrator of DEM’s Office of Air Resources, told ecoRI News, “I’m not exactly sure why, what’s taken so long. We really haven’t done anything with the heavy-duty [emissions], and so there really isn’t a program that I can speak to because, I mean, it’s in its infancy.”

In a June 3 email to ecoRI News, Jay Wegimont, DEM’s programming services officer, wrote, “DEM’s Office of Air Resources continues to partner with the DMV in developing a heavy-duty inspection and maintenance (HD I&M) program. The goal is to finalize Heavy-duty I&M Regulations by the end of 2022 with a program launch in 2023.”

Besides enforcing existing laws, Rhode Island could drastically lower the transportation sector’s climate-changing emissions by: increasing RIPTA funding and support to spur increased ridership; building and connecting more pedestrian and bike paths; designing safer streets that encourage the use of bicycles, rollerblades, skateboards, and scooters; better incentivizing the buying/leasing of electric vehicles and funding the installation of more charging stations; and incorporating bus-only lanes on the roadways the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) loves to widen.

Barry Schiller, a longtime transit advocate and a former RIPTA board member, rattled off a list of inequities that pervert Rhode Island’s transportation choices: clearing roads of snow for cars but not sidewalks for pedestrians; expanding parking around the Statehouse but not putting up a bus shelter for those who use public transit; proposed tax relief for drivers of fossil fuel-powered vehicles but nothing for those who drive electric vehicles or don’t drive at all; and the proposed ending of property taxes on cars with no help for those without cars.

Even as the problems fueled by a changing climate now routinely present themselves — back-to-back near-90-degree days two weeks ago in Greater Providence — and last year’s Act on Climate law that requires the Ocean State to substantially reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, politicians continue to file pro-car legislation and RIDOT clings to a bygone era.

In February, lawmakers introduced a bill to amend state law concerning sidewalks. Their two-sentence amendment was this: “All maintenance of sidewalks along state highways shall be the responsibility of the state. Such maintenance shall not include snow removal, sweeping and cleaning.”

RIDOT continues to favor the car-dominant status quo while often fighting initiatives that improve bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure — modes of transportation relied on by those who can’t afford to own a car.

The agency’s director is among those who spent five years trying to dismantle Providence’s central bus hub in favor of a patchwork of bus stops in other areas around downtown, including Allens Avenue — a road heavy with truck traffic and caked with industrial pollution.

RIDOT’s embedded old-school mentality continues to embrace the fallacy that more highway lanes will reduce congestion. It is why the rebuild of the 6-10 Connector failed to free Olneyville — a Providence neighborhood that is 64% Latino and 11% Black — from 70 years of isolation.

RIDOT officials contend the agency’s 10-year transportation plan has “created a generational investment focused on key infrastructure priorities including rehabilitating bridges in critical need of repair, reducing carbon emissions, increasing system resilience, removing barriers to connecting communities, and improving mobility and access to economic opportunity.”

Most motorists do or should acknowledge RIDOT has done a fine job maintaining and repairing motor vehicle infrastructure under the leadership of its current director.

As for RIDOT’s contention that it is reducing carbon emissions and removing barriers to connecting communities, most transit and environmental justice advocates vehemently disagree.

Transit advocates rallied across the street from the Statehouse in early February to highlight the inequities they said are embedded in transportation investment. They noted the vast majority of government investment in Rhode Island transportation goes toward maintaining, improving, and expanding roads and highways, often at the expense of projects such as expanding public transit or adding bicycle lanes.

“We want to raise the voices of those who depend on public transit, whose social, economic and political futures are dependent on a good transit system,” RIPTA rider Rochelle Lee said at the Feb. 11 event.

All study and no action

Both of the 2020 plans Tanzi referred to in her April 26 testimony — Transit Forward RI and the Bicycle Mobility Plan — were written to provide a pathway for Rhode Island to reduce its transportation-sector climate emissions.

Besides helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Transit Forward RI was designed to enhance mobility for residents, workers, and visitors. The 70-page report also notes that those who do not use public transit benefit from increased economic activity, less traffic, cleaner air, and a “more livable and attractive state.”

The Bicycle Mobility Plan took a detailed look at the needs surrounding bicycle infrastructure in Rhode Island and identified strategies and projects that could help close service gaps and better connect the state.

These two studies, however, are not the only ones recently conducted to help improve Rhode Island’s transit system and provide more transportation choices.

RIPTA and the agency’s Human Services Transportation Coordinating Council are working to update the RI Coordinated Public Transit + Human Services Transportation Plan.

The plan, last done in 2018, is updated every five years to consider the changing transportation needs of individuals with disabilities, older adults, and people with low incomes; provide strategies for meeting those needs; and prioritize services for funding and implementation.

Four listening sessions were recently held to hear ideas from RIPTA users, advocacy organizations, and the public. ecoRI News attended the April 27 online session. Participants spoke about, among other things, a need for urban bus improvements, increased service hours and routes, and expanded service into rural areas.

The last RI Coordinated Public Transit + Human Services Transportation Plan features public comments urging RIPTA to better align bus service with other transit infrastructure.

“Would like to see a recognition of the impact of transportation on health outcomes and see a plan for transportation infrastructure that supports active living such as walking, biking, etc.,” one commenter wrote. “Active transportation can be facilitated by the accessibility of buses aligned with safe walking routes for example, which can impact overweight and obesity rates, and rates of diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and depression.”

RIDOT’s 10-year transportation plan, the State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) 2022-2031, envisions “a multimodal transportation network that connects people, places, and goods in a safe and resilient manner by providing effective and affordable transportation choices that are supportive of healthy communities, provide access to jobs and services, and promote a sustainable and competitive Rhode Island economy.”

Listed among the plan’s goals and objectives are: improve regional connectivity; design roadways to increase transportation choices; improve individual and community health; create a network of open space and trails; and reduce transportation-sector greenhouse gas emissions, traffic congestion, and vehicle miles traveled.

The 2021 Clean Transportation and Mobility Innovation Report notes the importance of a transit future built “upon core values of innovation, equity, public health, and economic development.”

The 169-page report also notes that, because the transportation sector is the top contributor of greenhouse gas emissions in Rhode Island, it is impossible to meet the state’s emission-reduction goal of 80 percent by 2050 without “aggressively transforming” the way the state moves people.

To do so, the report says, “Bold initiatives to electrify motorized transportation, expand public transportation options, and encourage infrastructure as well as community design that allows for active transportation are all needed.”

All of these plans are chock full of great ideas, clear-eyed visions, and 21st-century recommendations. The problem lies with a car culture that dominates Rhode Island’s transportation landscape and a lack of plan implementation.

“[D]espite the fact Rhode Island has developed very detailed blueprints for investing in transit, as well as in bicycle mobility, we have not yet taken a step to fund the implementation of those plans,” John Flaherty, deputy director of Grow Smart Rhode Island, said during that late-April House Finance Committee hearing.

Flaherty was among other advocates who were testifying at the Statehouse hearing in favor of a few environmental justice bills related to transportation, climate change, and affordable housing construction.

Among those bills was a proposal for a $100 million 2022 bond referendum that would fund Transit Forward RI recommendations and a $25 million bond referendum that would fund Bicycle Mobility Plan suggestions.

“[T]here is huge potential for mode shift from vehicles to transit and the reason I say that is because nearly 80 percent of our state’s population already lives within a 10-minute walk of a transit stop,” Flaherty said, “and yet less than 3 percent of the state’s population uses it as a means to get to work. I know why that is because I use transit. It’s the fact the hours of operation aren’t what they need to be; in fact, my wife is here to pick me up tonight because I can’t get home by transit.”

A fleet of 240 RIPTA buses, covering 59 statewide fixed routes, provide 2,794 daily trips on weekdays, 1,641 on Saturdays, and 1,123 on Sundays. RIPTA transports about 58,000 people daily.

Fifty-three percent of RIPTA riders are people of color; 81 percent lack dedicated access to a car; and 39 percent live in households with annual incomes less than $10,000, according to a 2019 RIPTA study. They also overwhelmingly live in the urban core: 53 percent live in Providence and another 10 percent live in Pawtucket.

Flaherty also noted the frequency of RIPTA buses isn’t sufficient for people to ditch their cars. As an example, he has noted a bus ride from Central Falls to Quonset (about 30 miles) can take one and a half hours one way — about twice the time it takes by car.

“The point is the state has the bones for a first-class transit system; we just haven’t made the investment yet,” he said. “I’m excited the Legislature is actually stepping up to do what the state administration, through the State Planning Council and the state Transportation Advisory Committee, have failed to do, which is to adequately invest in these plans. I will just remind you that we are investing hundreds of millions of dollars still in expanding highway capacity, which we know is going to induce more driving, more emissions.”

One way

The nation’s roadways were hijacked in the 1920s when General Motors, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil, Phillips Petroleum, and others conspired to dismantle the U.S. streetcar system.

When the crusade to destroy the country’s popular rail-based public transit system began, only one in 10 Americans owned a car. There are now some 287 million cars registered in the United States. Americans, at least before COVID, collectively spent some 4 billion hours stuck in traffic annually, wasting about $90 billion in fuel and lost productivity.

Besides dismantling a robust public transit system, the shift to cars also helped to make walking less popular and more dangerous. It also ushered in unceasing increases in transportation costs.

The average U.S. household spends 16 cents of every dollar on transportation, and 93% of this goes to buying, maintaining, and operating cars, the largest expenditure after housing.

In 2016, when regular retail gasoline prices averaged $2.14 a gallon, owning and operating an average sedan cost $8,558 a year, according to AAA, which was equal to $713 a month or 57 cents a mile.

The cost of car ownership only continues to increase, even as wages remain mostly stagnant. From 1975 to 2020, the average cost of car ownership increased from 14.4 cents per mile to 63.7, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Even as the cost of car ownership moves further out of reach for impoverished people and the climate emergency grows increasingly dire, disproportionately impacting the lives of society’s most vulnerable, there has been no collective effort in Rhode Island to improve and expand public transit, despite those taxpayer-funded plans that stress the importance of getting people out of cars.

Efforts to implement a vehicle miles traveled tax haven’t moved beyond some task force or study commission possibly exploring the feasibility of such an idea — a penny per mile would generate about $30 million annually for Rhode Island public transit and infrastructure improvements.

Before the pandemic struck in 2020, public transportation in parts of the country — not necessarily in Rhode Island, where government inertia has killed many progressive ideas about transit — was thriving and a new mobility era was emerging.

In a 20-year span from 1997 to 2017, public transit ridership rose 21%, as total passenger miles traveled increased 14.6 billion to 57 billion, according to a 2019 report by the American Public Transportation Association.

The 52-page report also noted that “77 percent of Americans think public transportation is the backbone of a multi-transit lifestyle.”

The Washington, D.C.-based organization also noted that every $1 invested in public transportation generates $5 in economic returns; every $1 billion invested in public transportation supports and creates about 50,000 jobs; home values are up to 24% higher near public transportation than in other areas; hotels in cities with direct rail access to airports raise 11% more revenue per room than hotels in those cities without; traveling by public transportation is 10 times safer per mile than traveling by automobile; public transportation saves the United States 6 billion gallons of gasoline annually; and communities that invest in public transit reduce the nation’s carbon emissions by 63 million metric tons annually.

Despite the economic, social, and environmental advantages created by public transit, 45% of Americans have no access to buses, trains, streetcars, trolleys or ferries, according to the American Public Transportation Association.

Rhode Island, as Flaherty noted during that committee hearing in April, has the bones to build a first-rate public transit system and the ability to reduce carbon emissions, but lacks the political will to make it happen. Unless that changes, expect a bevy of Act on Climate lawsuits to be filed.

To view the series, click here.

Time to close DOT permanently, or at least until it gets a Director who gets the future instead of living in a car centric past

excellent and comprehensive!

The car culture, once established, indeed gets deeply rooted. Those with cars, which is most of us including me, reason why not take advantage of the convenience of coming and going when you want, in RI usually you can even park close to the door wherever you go. Politicians have to pander to all the motorists, hence the expanded highways, priority for tax reductions on driving. Corporations too understandably move out to where parking is easier/land is cheaper – think “Neighborhood” Health Plan, Fidelity, CVS, Citizens Bank, and the DOT facilitating all that with Route 99, widening Route 7, a new interchange on I-295….

Of course the problem with all the individuals/companies so reasoning, is the gradual ruin of the cities, countryside, and the climate, plus all the accidents and energy dollars flowing out of state. But in this “tragedy of the commons” situation, ruin is inevitable unless we can mutually agree to voluntarily accept restraints on the car culture and implement the alternative visions being developed.

the article is very interesting as are greg and barry’s comments (who are friends of mine). i agree that the availability of public transit should be extended to the suburbs and made convenient with 24 hour service if justifiable. boston being an obvious example. however RI is not boston so advocating for a more robust suburban public transit service which allows a few people to get home at midnight is totally wasteful. emphasis to improve public transit in areas where people are carless would be a more productive focus on the improvement of public transit.

regarding the development of bike paths and walking paths as an alternative to driving to work is a bit ridiculous unless you are 23 years old and live a mile from work, and even then it is ill advised in the winter. people have a lot of time obligations in their life and to imply that they should spend an additional couple of hours a day riding public transit is unrealistic.

this article cherry picks a lot of statistics to argue a case implying that bike and walking paths and a massive public transit system is the remedy to climate problems and the congested highways when in fact they are not. i ve worked out of the house for 33 years but on a typical field day i ll drive 250 miles and have six site inspections. i need the highways clear not bumper to bumper from connecticut to the cape.