Rising Waters Put Historic Coastal Properties at Significant Risk

No one strategy can protect landmarks in Newport, Wickford, and other vulnerable locations along the Rhode Island shoreline from rising seas and nuisance flooding

August 6, 2020

NEWPORT, R.I. — On her first day of work at the Newport Restoration Foundation in 2015, Kelsey Mullen arrived late. The house in which she was living had flooded again, and water on the street rimmed her car’s tires.

The Bridge Street home in the city’s historic Point neighborhood is at a confluence of water sources near city storm drains and Newport Harbor, so its stone foundation provides little barrier to storms or high tides. The ground is often saturated and slopes gently toward the house, so water has nowhere to go but inside and all around. The basement perpetually smelled like the sea, Mullen said, while sump pumps and dehumidifiers kept busy.

Built in 1725 by famed furniture maker Christopher Townsend, 74 Bridge St. sits just 4 feet above sea level. Luckily, it hasn’t sustained permanent damage, but the home is a stunning reminder of what could happen to entire neighborhoods if action isn’t taken to protect them from the damaging effects of increased water.

The Environmental Protection Agency reports seas have risen 10 inches since 1880, and they are projected to swell as much as 3 feet during the next 50 years. Coupled with flooding from chronic rain events, coastal houses like this little red Colonial and historic business districts from Narragansett to Westerly and Warwick to Bristol will be underwater.

“This is the canary in the coal mine, where rising water is impacting this house and we will see impacts in other houses,” said Mullen, now the director of education at the Providence Preservation Society. “With this issue, there are no experts, there is no benchmark. If you’re waiting for an official sanctioned recommendation, it’ll be too late, and there will be loss along the way.”

Since seaports and coastal communities were settled first historically, there are billions of dollars of valuable resources in harm’s way statewide.

“Back in 2007, there was the feeling that, ‘Let’s not worry about it,’” said Wakefield-based historic preservation expert and community planner Richard Youngken. “Now everyone is concerned because it’s getting worse.”

Guidance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the National Park Service provides approximate courses of action, while urgent pressure to find a solution forces cities and towns, preservationists and engineers, individual organizations, and homeowners to assess risk, then develop and execute a specialized strategy on their own.

This triggers inconsistent approaches, because what works for one house or municipality, might not work for another, said Arnold Robinson, historic preservationist and regional planning director for Fuss & O’Neill engineers in Providence.

“Flooding varies in different hydrologies and geographies, so what happens in Louisiana is different than Vermont, and how they deal with it is different. So that leaves us preservationists to figure it out, and share solutions with each other,” Robinson said. “There is a lack of funding for this adaptation, too. We are not investing in making historic resources more resilient. And if you look at the economy of New England states, history is our economic engine.”

A ‘future archipelago’

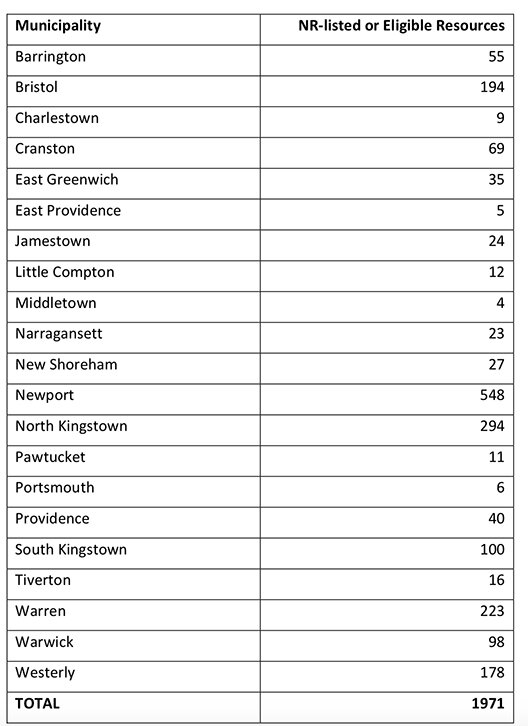

Initiatives in Newport and North Kingstown, most notably in its village of Wickford, which are at the Ocean State’s risk epicenters among its 21 coastal municipalities, show progress. These two coastal communities alone boast 842 historic structures of 1,971 statewide, wrote Youngken in his 2015 report Historic Coastal Communities and Flood Hazard: A Preliminary Evaluation of Impacts to Historic Properties.

With more than $432 million of historic properties within FEMA flood zones, he reported, Newport has the most to lose. A lion’s share of the City by the Sea’s historic district and tourism cash cow could be swallowed by water, including original Colonial buildings on Bowen’s Wharf, Market Square, the historic Brick Market and lower Washington Square, Long Wharf, and The Point, and most of the Fifth Ward and Ocean Drive, according to Youngken.

“Imagine flooding all along Thames Street and everything west of Queen Anne’s Square,” Youngken said. “With sea-level rise, all of that comes into jeopardy, so you lose a big portion of the city. The same is true of Wickford. Rhode Island would become a series of islands — our future archipelago.”

Hoping to stem the deeper existential forces of climate change-induced flooding and sea-level rise, Newport this year issued the state’s first guidance plan for residents to elevate their historic properties. These voluntary guidelines clarify what the city will examine with homeowners’ elevation requests, as well as provide additional advice for materials, siting, options for building accessibility, decreasing hardscapes, and increasing green space and drainage to eliminate excess water in overburdened municipal systems.

“Resiliency to climate change, and specifically the threat posed by rising sea levels, is a fundamental component to the city’s long-term historic preservation goals, and these guidelines speak to that,” said Newport’s historic preservation planner Helen Johnson. “For several years, we’ve been exploring how rising sea levels are projected to impact some of our most historically significant and environmentally sensitive neighborhoods. And while we can’t control the tides, we can influence how we respond as a community.”

In some cases, elevation may not be ideal. It’s expensive, costing between $40,000 to $250,000, and myriad limitations could stymie the most steadfast preservationist. Many houses on The Point, for instance, are situated on the front property line, with their front steps on the sidewalk, so building access is essential to consider, Johnson said, as is drainage and so much else.

“Some homeowners can move the house back, others cannot, so you have to get creative,” she said. “It also impacts the historic streetscape. Some preservationists argue that this approach defeats the purpose, as does relocating the house to drier ground.”

City officials, including the Historic District Commission that drafted the guidelines and will review all future elevation applications, said they recognize that for homes in some of Newport’s more vulnerable areas, elevation is the best route to preservation. The Point has set the elevation precedent during the past century, with many houses already raised since the hurricane of 1938, Johnson said.

The new guidelines complement a series of flood gates buried at vulnerable spots in the city, including the Wellington Avenue and The Point neighborhoods. Another is planned for King Park. The gates act as tourniquets to stop salt water from rushing in from the harbor and to allow stormwater to drain from higher areas.

Though flooding still occurs, especially at high and king tides, Johnson noted that they quickly proved to be a viable option to mitigate flooding.

“But these types of infrastructures can only get us so far,” she said. “The other side is elevating buildings and preparing our aboveground infrastructure as well. But depending on a house’s location in the flood zone, it might have to go up really high. So, when is it not feasible to elevate it, and if you move it, where does it go and does it lose its historic significance? We don’t have those answers, and don’t touch on that in these guidelines, because we wanted to focus on what was achievable.”

On ‘verge of disasters’

Nonprofits like the Preservation Society of Newport County (PSNC) and the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF) are paying attention to those unanswered questions.

PSNC’s 266-year-old Hunter House is perched a few meters from Newport Harbor, its basement floods regularly, and its Bannister’s Wharf store frequently sees water just inches from its front door, according to the organization’s executive director, Trudy Coxe. It hasn’t lost anything yet, she said, but its staff has become adept at relocating both buildings’ contents while they consider contingency solutions, including elevation and amphibious technology.

“Hunter House was even built to endure flooding, so it’s set back slightly and has a small plot of land. But that house is at risk, which is true for a lot of houses along Washington Street,” Coxe said. “I don’t think any state in America is doing enough. One of the things that gets in the way of doing more is that we don’t know what we should be doing. The solutions are incredibly expensive. Plus, people think they can pass it to the next generation, or that someone will come along and wave a magic wand and it will all go away.

“But predictions are pointing to it getting rougher out there. We are on the verge of disasters.”

The NRF is equally concerned. It has preserved and restored more than 80 homes from the 18th and early 19th centuries, 25 of which are in The Point, including 74 Bridge St. Though it hasn’t adapted or elevated its houses to accommodate excessive water, that’s not to say the organization won’t, according to executive director Mark Thompson.

Though the NRF sold 74 Bridge St. in early July, Thompson said he suspects it’s a candidate for elevation with its new owners’ rejuvenation plan.

“A lot of people think that The Point is the focal point of the climate-change issue in Newport, but we are not just interested in our houses, we are interested in Newport, because if we save 25 houses, and nobody else is able to do that, then there is no point in it,” Thompson said. “Cities around the world say infrastructure should be erected, like gating systems, and elevating or relocating houses to preserve the integrity, but how high do you raise it to be effective? Our goal is to save the houses where they are, and that we save them the right way.”

NRF’s interest in that signature property inspired it to launch a national conference where experts discussed these issues and possible solutions. Its inaugural Keeping History Above Water event in Newport in 2016 became a huge success, said Mullen, who was then NRF’s public program manager. Since then, it has spread to other coastal communities, including St. Augustine, Fla., Annapolis, Md., and Palo Alto, Calif.. The conference is scheduled to be held in Charleston, S.C., next year.

J. Paul Loether, executive director of Rhode Island’s Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, also is trying to create an intelligence clearinghouse to help municipalities, homeowners, and nonprofits streamline strategies. As experts in knowing what properties are significant across the state, the Providence-based commission wants to secure funding and political influence to amplify preservation and to identify the highest risk areas and better equip municipal planners.

“Newport’s solution will work for them as a city, but we need to be more strategic as a state,” Loether said. “It doesn’t take much to visualize Main Street in Wickford being underwater. So, we want to give them the best information we can. But there is no easy answer. It raises philosophical issues, financial issues; where is the tipping point? I have seen houses in Connecticut raised 12 feet and it looks like Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds.’ But others you can’t even tell.

“It’s not driven by preservation in many cases, it’s driven by the rising cost of FEMA flood insurance. If you’re dealing with a single structure, it’s one thing, but the whole neighborhood? Are you going to raise the street? Then you have to wonder, are we preserving history or preserving the property? Then the bigger issue is, do you really have a historic district?”

From the Ocean State to the Golden State, there are more questions than answers, which is precisely why the approach is scattershot. But as storms become more frequent and intense and nuisance flooding becomes more routine necessity will drive activity. Though no residents in Newport have received elevation approval yet, Johnson, the city’s historic preservation planner, remains optimistic that this is the way forward.

“We want to get these communities together to learn from what we’re doing here in Newport and see if we can help other municipalities develop their own guidelines,” she said. “We are such a small state but we are so diverse in our building stock and municipal resources, so we need to discuss the impacts and things we can do to tackle sea-level rise and floodwater.”

In the meantime, there are tough truths we must face, Mullen said.

“In terms of cultural heritage, there are only a few possible reactions: you either raise up structures; you relocate structures; or you retreat,” she said. “And ultimately, maybe 100 years, retreat is the only predictable outcome. We’re not seeing reversal in climate trends, and climate scientists say the projections are too conservative. So, if we know the conditions are unlikely to change, we have to change the way we live, and make proactive decisions now about what we’re willing to lose and what we’d like to keep.”

Is there any option to create sea walls using a stone facade exterior to mimic the stone fences that already exist throughout the state? Not sure how that would work within keeping the historical value but maybe in combination with some raising of houses?