Invenergy Failed to Make Case for More Fossil Fuels

June 24, 2019

WARWICK, R.I. — In swift and stunning fashion, the Energy Facility Siting Board (EFSB) denied what would have been the largest power plant in the state and one of the largest natural gas facilities in New England.

The $1 billion Clear River Energy Center endured the longest application process of any energy facility since the state siting board was created in 1986, taking 3.5 years to meet its demise. The EFSB, though, needed less than three hours of discussion to dispatch the application by a unanimous 3-0 vote. It was the first power plant application the EFSB has denied.

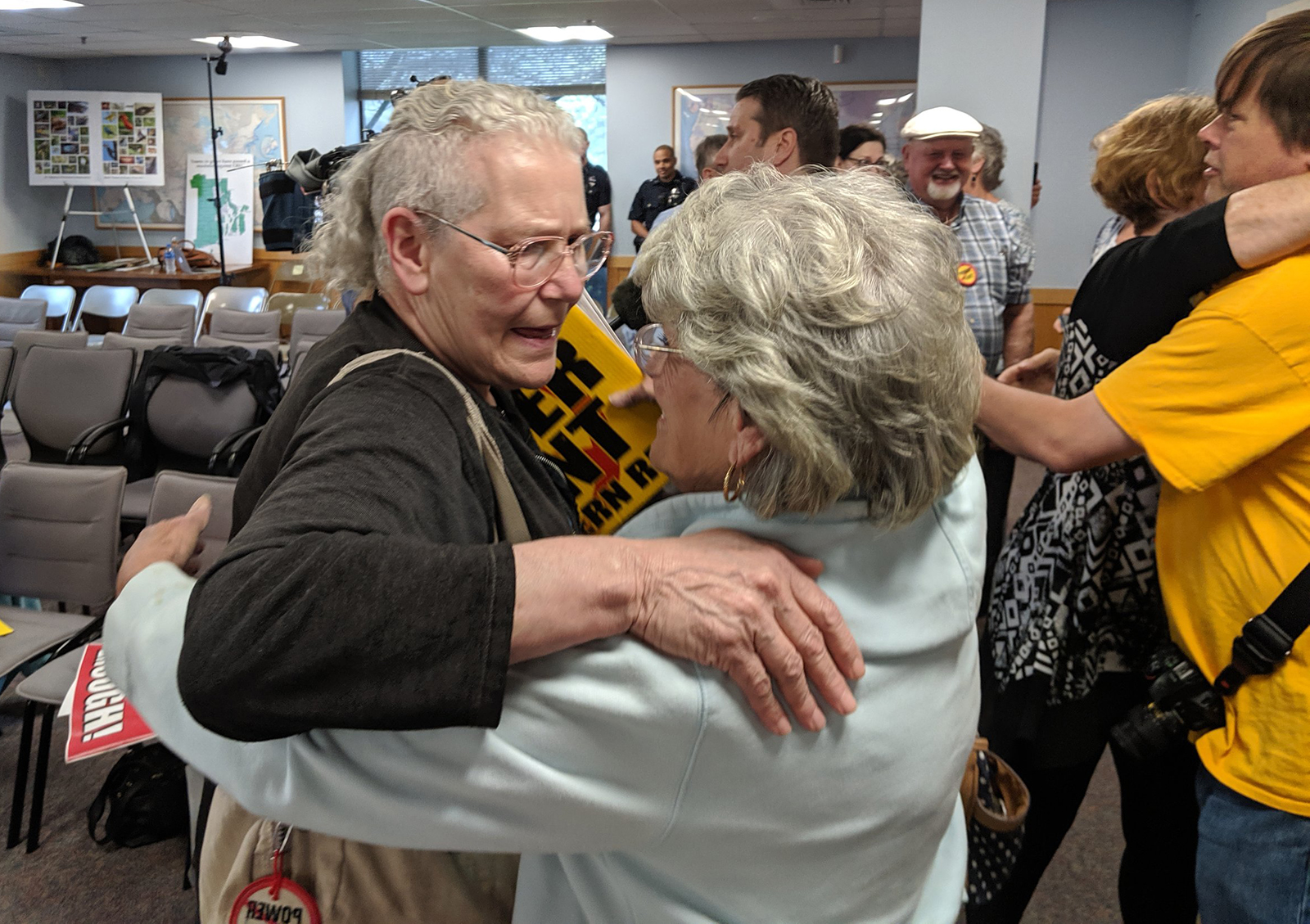

Opponents of the project, who built a formidable campaign and were a steady presence with signs and T-shirts at more than 30 public hearings, were taken aback by how quickly the EFSB rejected the application.

“I never expected it to be over so soon,” said Mary Pendergast, ecology director for the Sisters of Mercy in Cumberland, “but I am very happy that Rhode Island will not be contributing to massive noxious emissions and to deforestation.”

The board may have tipped its intentions early, when its first of many expected motions was to reject the argument that the power plant was needed. The “need” issue was one of three criteria the applicant, Chicago-based Energy Thermal Development, had to satisfy to receive a license to build and operate the Clear River Energy Center (CREC).

Board chairwoman Margaret Curran allowed fellow EFSB member Janet Coit to lead the discussion about need. Coit, who heads the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, steered the conversation on complex matters throughout the application process. At the June 20 meeting, she dispatched some of the unresolved issues around need that were expected to be parsed and debated by the board.

Invenergy championed from the outset its fast-starting, lower-emission facility as the regional bridge from fossil fuel power to renewable energy. CREC would be the backstop for older oil, coal, and natural gas facilities to reliably deliver electricity during cold snaps and heat waves, Invenergy argued. The facility was promoted as a steady electricity supply as renewable energy projects and related infrastructure gained a foothold on the regional power grid.

When wind and solar finally achieved scale, Invenergy said CREC would be a standby facility to fill power gaps created when there wouldn’t be adequate sun or wind to deliver renewable energy.

That argument may have held up in late 2015 when the application was filed, but the unanticipated influx of renewable energy, combined with other new natural gas plants, improved energy efficiency, and the extended use of older power plants, created a surplus of electricity in the grid.

In its closing report to the EFSB, Invenergy referred to state guide plans confirming the need for such a bridge facility, but Coit and EFSB member Meredith Brady, who heads the Division of Planning, downplayed those reports as simply general overviews of issues that served as guides for making decisions. The state planning documents aren’t mandates in themselves, they said.

Brady compared the planning documents to aerial photos. “They’re guides. They’re general in nature. They’re not the experts on the topic.”

Coit said the CREC conforms with state guide and energy plans, but “to me, that’s not evidence on need.”

Even if the plans were able to offer insight decades ahead, “It seems like the trends are for decreasing demand and so it wasn’t a compelling point anyway,” Coit said of Invenergy’s reliance on the guide plans.

Another gray area was whether CREC, which could operate as long as 50 years, would be needed to provide electricity when existing natural gas and oil facilities were decommissioned. There was never a reliable third-party report that specified the need for conventional power plants beyond 10 years. Invenergy often referred to reports by ISO New England identifying some 6,000 megawatts from power plants “at risk” of retirement. But the analysis never projects much beyond the years when the proposed power plant would have been in its early years of operation.

The EFSB acknowledged that the reports by ISO New England, the operator of the regional power grid, lacked the long-term needs analysis for new power plants. But in its more recent forecasts, known as Capacity, Energy, Loads, and Transmission (CELT) reports, the regional grid operator recognized that renewable energy was adding power to the grid faster and in greater amounts than anticipated. ISO New England also noted that energy-efficiency programs were reducing current and long-term electricity demand.

Coit said the CELT reports were reliable and credible, and not rebutted effectively by Invenergy. She said Invenergy’s energy expert, Ryan Hardy, was less convincing than experts who testified against the power plant. Hardy, Coit and Curran both said, came across, at times, as an advocate instead of an expert and gave evasive answers when his conclusions were questioned. They noted that it hurt his credibility that his repeated predictions about power-purchase agreements never materialized.

“It certainly was a problem for him that consistently his estimates and predictions for the future were shot down again and again. And was really confident about them. And he was wrong,” Curran said.

Brady added that Hardy and his predictions were undermined by the quickly shifting energy landscape.

“It was unfortunate for him that the environment that we are examining is larger than that set of facts,” Brady said. ”And that’s what we have to take a look at here is the entirety.”

Hardy’s assertion that having a power-purchase agreement from the regional grid operator proved the power plant was needed worked against him once Invenergy lost its agreement and failed to secure a new one for three consecutive years.

Both Coit and Curran agreed that credibility was a major factor in their decision-making. They mentioned misleading assertions by Hardy and the Chicago developer about Invenergy’s appeal to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to have ratepayers fund CREC’s connection to the electric grid, a project that would have cost about $168 million. Coit also noted that Invenergy misrepresented itself when it acquired maps of the proposed construction site from The Nature Conservancy.

The EFSB emphasized the convincing testimony of energy experts who testified against the power plant on behalf of the town of Burrillville and the Conservation Law Foundation.

Robert Fagan, of Cambridge, Mass.-based Synapse Energy Economics, was praised for effectively arguing that the CELT reports showed a declining demand for electricity from fossil-fuel power plants. Coit said Fagan was “the most compelling of the witnesses on this particular point.”

The EFSB put heavy emphasis on the capacity-supply obligations (CSOs), the long-term power-purchase agreements awarded by ISO New England to power plants and other energy suppliers to the power grid. CSOs are prized by developers because they ensure a fixed revenue stream, thereby making projects more appealing to investors and lenders.

Coit noted that the annual CSO auctions were attracting bids above the amount of electricity ISO needed to keep the lights on in New England. As a result, power-purchase contract prices dropped significantly for three straight years.

To the EFSB, the drop in price and increase in supply answered the question of long-term need for the CREC. Energy project developers, they reasoned, were building projects with a 20-year or longer time horizon and, as such, the power-purchase auction results were showing that there would plenty of power sources to meet the demand in the decades ahead.

Invenergy was therefore hurt by the long application process. In 2015, ISO New England awarded its highest contract price at $17.73 per kilowatt-hour for a CSO. But by 2019, the price had dropped to $3.80 per kilowatt-hour. Meanwhile, the amount of electricity vying for a CSO was some 6,000 megawatts above the amount needed in for the 2016 auction and jumped to nearly 10,000 megawatts above need this year.

Invenergy argued that the southeastern New England region of the grid had a low supply, but ISO New England never acknowledged the constraints because it kept power-purchase prices the same for all six states.

Invenergy received a CSO contract in 2016 for power from one of CREC’s two generators, but in an unprecedented decision, ISO New England rescinded the CSO in 2018. Invenergy blamed opponents for stymieing the vetting process and inferred that the EFBS allowed too many delays and suspensions of proceedings.

The lack of a CSO was the reasoning used by the Connecticut Siting Council (CSC) in 2017 to deny a 550-megawatt power plant proposed for Killingly, on a site some 15 miles from the proposed CREC location.

It should be noted that the Killingly power plant was approved by the CSC on June 6, after it received a CSO earlier this year. The initial denial by the CSC was without prejudice, leaving open the option for the developer to reactivate the application. Rhode Island’s EFSB decision, however, doesn’t allow the application to be reopened. Invenergy would have to file an entirely new application if it wants to restart the project, a process that would likely takes years to advance.

Although ISO New England agreed that Invenergy’s protracted application effort was the reason for rescinding the CSO, the EFSB noted that the delays weren’t its doing. Curran said there was criticism from outside sources suggesting the EFSB was to blame.

“We should get credit for moving along as well as we could given a number of things that came up that the parties acknowledged, made it imperative that we pause,” Curran said.

Coit noted delays were because of Invenergy’s struggle to find a source of cooling water for the power plant and caused by Invenergy’s appeal of the loss of its CSO to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

“When there’s no water supply plan, there’s no ability to run a facility of this kind,” Coit said.

Jerry Elmer, senior attorney for the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), one of the project’s primary opponents, called it a “colossal mistake” that Invenergy filed its application prior to having an agreement for a water source. As it struggled to secure a deal, the project was further delayed because Invenergy switched its cooling system design to one that required less water.

Proceedings were also delayed by the interconnection funding controversy. An initiative that irked the EFSB, as Invenergy promised from the onset that it wouldn’t ask ratepayers to pay for CREC.

“That these were mistakes and botches over and over again on the part of Invenergy, that caused delays that Invenergy then blamed the EFSB for,” Elmer said.

Invenergy may appeal the decision in state Supreme Court, but Elmer and other legal experts have told ecoRI News that the court gives deference to the EFSB’s decision. Elmer said CLF will litigate against Invenergy if the decision is appealed.

“I think it would be wise for Invenergy not to appeal because they are not going to win on an appeal,” Elmer said. “You can always appeal. It doesn’t mean you are going to win.”

If Invenergy can prove it meets the need criteria, it still has to show a financial benefit and answer the question of acceptable environmental harm, an issue the EFSB never addressed and opponents built a considerable case against.

Invenergy said it will review the EFSb’s written decision before making a move. But the company likely has the money to make a comeback. The energy developer received $26 million by selling the CSO for the two years it couldn’t provide electricity because of construction delays.

Ultimately, it was a rapid change in the energy landscape and markets that doomed the project.

“Because the case took three and a half, almost four years to litigate, we had the benefit of year after year, after year, after year, after year of new ISO information coming out,” Elmer said.

The passage of time may only make it harder for Invenergy to build a fossil fuel power plant, as the growth of renewable energy accelerates and energy-efficiency and energy-storage programs advance.

“Any company could file a new application for a new power plant tomorrow, because it’s a new application,” Elmer said. ”But as a practical or economic matter, no power company has an economic interest in doing that with the energy market being the way it is now, because they wouldn’t make any money. So I don’t think we’re going to see another application tomorrow.”

EXCELLENT Thanks for covering this important issue!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!