Friends Gather to Help Protect Warwick Pond

August 26, 2016

WARWICK, R.I. — Philip D’Ercole has lived along the banks of the Warwick Pond for 13 years. In that time, he said he has watched the pond become increasingly stressed.

“We need to bring the pond back to levels where we’re not hesitant to go swimming,” D’Ercole said. “We should be able to enjoy our water resources.”

The Edgehill Road home of he and his wife, Carmen, abuts Warwick Pond. In fact, the proximity to the pond made the location an attractive place to retire. The couple enjoys boating and fishing, but they don’t eat any of the fish they catch, and they don’t go swimming. This year, D’Ercole didn’t even put his boat in the water. He tells his guests not to bother bring bathing suits. He forbids his grandchildren from swimming in Warwick Pond, even as they watch others splash away.

Water quality sampling — done by URI Watershed Watch volunteers since 1995 — says Warwick Pond is safe for swimming, at least most of the time. On Aug. 19, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) issued an advisement warning the public to avoid contact with Warwick Pond because of probable blue-green algae. Cyanobacteria blooms can release toxins that can make both humans and animals sick.

DEM noted that “anyone who comes into contact with this water should rinse their skin with clean water as soon as possible, bathe, and wash their clothes. If a pet comes in contact with this water, the pet should be washed with clean water.”

Last summer, DEM issued a similar advisement in August warning the public not to swim, fish or come in contact with Warwick Pond.

D’Ercole said last summer’s algae bloom was one of the reasons he didn’t bother with his boat this year. “The pond looked like pea soup,” he said. “They told us to pull our boats out of the water but don’t touch the water. I was out there with surgical gloves on trying not to touch the water.”

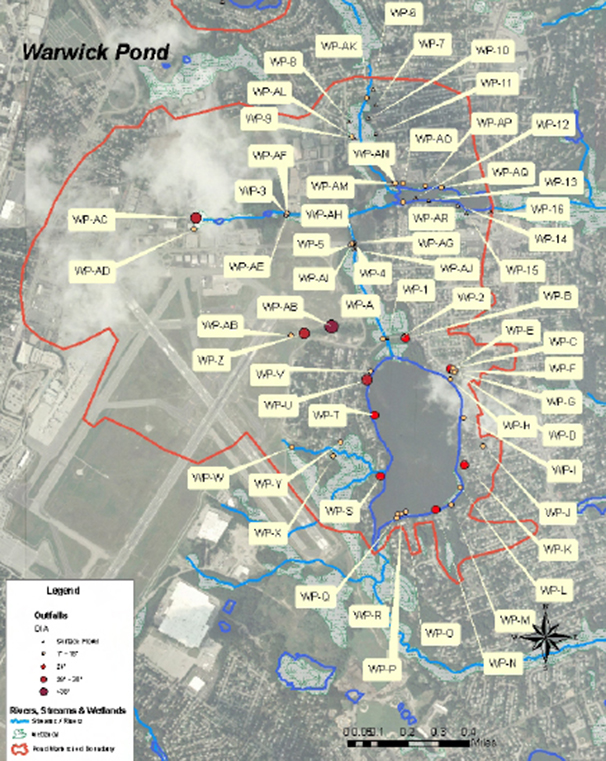

The Warwick Pond watershed is about 855 acres and much of that area is highly urbanized. Stormwater runoff flowing into the 85-acre pond is a problem that is slowly being addressed. There are 44 identified storm drains and 16 areas of concentrated surface water flow discharging to Warwick Pond, its tributaries and hydrologically connected wetlands, according to DEM. Eleven of those storm-drain outfalls discharge directly into the pond.

The Warwick Pond watershed is publicly sewered, but not every home is connected. About a dozen or so homeowners still use onsite sewage treatment, such as a septic system or cesspool.

While there are some forested areas and vegetated buffers within the pond’s watershed, lawns on the western and southern shore typically extend to the pond’s edge, attracting waterfowl, pesticides and fertilizers. The birds’ waste and applied lawn chemicals, containing phosphorus and nitrogen, are eventually washed into Warwick Pond along with other stormwater contamination.

A 2007 DEM report noted that Warwick Pond requires a 46 percent reduction in phosphorus.

Also, just east of the pond and within its watershed is T.F. Green Airport, which occupies 1,100 acres. Two drainage ditches from the airport property discharge into the pond.

Data collected by the Rhode Island Airport Corporation indicates periodic violations of the dissolved oxygen standards in samples collected at the inlet and outlet of Warwick Pond during the winter, according to the 2007 study. These violations of the criteria are more likely associated with the discharge of glycol — the primary deicing compound at the airport — and not phosphorus from airport property storm drains, the state agency said.

“‘Eutrophic’ ponds have excess nutrients that promote growth of algae and vegetation. In an urbanized location, the excess nutrients typically come from fertilizer runoff, waterfowl fecal matter … In Warwick, deicing and anti-icing fluids used at T.F Green Airport also contribute to this issue. Gorton Pond, Warwick Pond, and Sand Pond are among nine eutrophic ponds studied in a RIDEM TMDL 2007 study. The water quality issues in these ponds exemplify the varied conditions and challenges of improving water quality in highly urbanized areas like Warwick,” according to the city’s 2013-2033 comprehensive plan for natural resources.

In May, the city of Warwick signed a consent agreement with DEM to meet the requirements of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Stormwater Phase II Rule of 1999. The law requires operators of municipal separate storm sewer systems — a city or town, a public agency, a municipal utility district or a flood-control district — to obtain permits and establish a stormwater management program that protects waterbodies by reducing the quantity of pollutants that can enter storm sewer systems during storm events.

Last year, DEM sent the city a notice of violation for its failure to properly implement a management program.

At a City Council meeting in early June, to discuss options for dealing with the pollution problems impacting the community’s water resources, Elizabeth Scott, deputy chief of DEM’s Office of Water Resources, noted that 33 bodies of water in the city didn’t meet state water-quality standards, and that Warwick Pond, Buckeye Brook, Gordon Pond and Sand Pond are all degraded.

Last November, D’Ercole and some other concerned residents formed Friends of Warwick Ponds, to help inform and educate the public about water-quality issues, to volunteer on environmental projects, such as water sampling, and, as property owners, to make changes that may collectively improve the health of Warwick Pond and its main tributary, Buckeye Brook.

The volunteer organization recommends not to feed waterfowl, pick up after pets, don’t overfertilize lawns, install a rain barrel and build a rain garden.

“We just can’t sit by and not help address the city’s water-quality problems,” D’Ercole said. “You don’t need lots of money to make a difference. You can accomplish plenty with passion and dedication.”