Oceanic Acid Trip Bad for Business

Ocean acidification could have a profound impact on marine life, and southern New England’s shellfish industry would be at risk.

January 18, 2016

Shellfish are arguably one of southern New England’s most valuable natural resources. Like the region’s many popular beaches, the area’s quahogs, oysters, lobsters and clams attract tourists. Clamming, as much as sunbathing, is a local summertime ritual.

Ocean acidification, however, a byproduct of the planet’s changing climate, is threatening shellfish and the industries they support. Studies have found that more acidic salt waters make it more difficult for oysters, mussels, scallops and other shelled mollusks to develop their hardened protection.

Shellfish rely on aragonite, a naturally occurring form of calcium carbonate, to generate their shells. Increased ocean acidity, however, means less aragonite, forcing mollusks to expend more energy to build shells and less on reproduction and survival.

Mark Gibson, deputy chief of marine fisheries at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, told the Providence Journal last year that ocean acidification is a “significant threat” to local fisheries.

In fact, a study published last year said the Ocean State’s shellfish populations are among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of acidification.

Ocean acidification — a change in pH accelerated by the absorption of carbon dioxide by seawater — isn’t turning coastal waters into hydrochloric acid, but it can have a profound impact on marine life, local businesses and southern New England’s way of life.

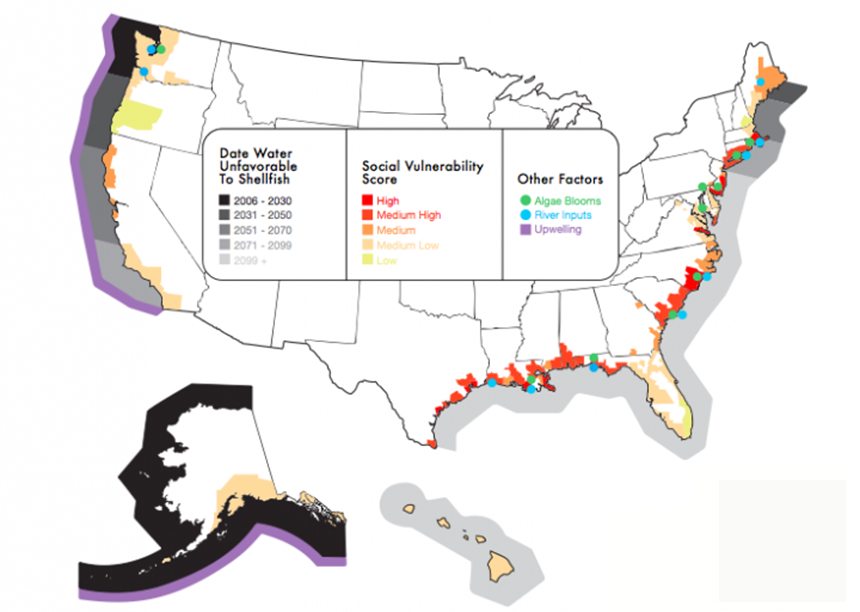

Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut are among 15 states whose shellfish industries are at long-term economic risk from the impact of ocean acidification, according to the 2015 study funded by the National Science Foundation.

Among the concerns, according to the study’s authors, is that many of the most economically dependent regions, such as Massachusetts, New Jersey and Louisiana, are least prepared to respond, with minimal research and monitoring assets for ocean acidification.

While Northeast fisheries face lower acidification rates than the Pacific Northwest, their vulnerability is higher, according to Lisa Suatoni, a senior scientist for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“Massachusetts and Maine are places that are just screaming for problems,” Suatoni told Climate Central last year. “New Bedford is the highest earning fishing port in the country. Eighty-five percent of landings are coming from one species: scallops. They’re really vulnerable.”

Southern Massachusetts brings in more than $300 million in shellfish annually, accounting for most of the region’s fisheries revenue, according to Climate Central.

Rob Rheault, executive director of the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association, told The Westerly Sun late last year that he is waiting for more scientific evidence to show how an increasingly acidic ocean will impact oysters and clams.

“Right now, the science on the impacts is weak,” he told the newspaper. “The only thing that we know for sure is that the larvae, in that first 48-hour period before they start feeding, are tremendously susceptible to dissolution. Their energy budget goes negative because they haven’t started to feed yet, and if they haven’t got enough energy in that egg and they’re starting to dissolve, then it takes extra energy to lay down shell, and they sometimes don’t make it.”

Acid hits

Oceans store dissolved carbon dioxide for hundreds of years, creating a large-scale environmental problem that is causing wholesale changes to ocean chemistry worldwide, according to a 2013 study.

Long Island Sound is just one example of acidification’s impact. The tidal estuary between Connecticut and New York is feeling the effects caused by excess carbon dioxide, according to the Connecticut Fund for the Environment. The New Haven-based nonprofit has noted that the sound’s low-oxygen dead zone forces finfish from local waters and kills shellfish.

Low oxygen levels (hypoxia) begin with massive algal blooms, caused largely by runoff that contains nitrogen and phosphorous. The blooms then die and decay on the seafloor, sucking in dissolved oxygen. Research from the University of Stony Brook suggests that bacteria feeding on the decaying algae also emit carbon dioxide, which reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid. Researchers at the New York university are examining the link between hypoxia and ocean acidification.

This dual threat is a considerable concern for both Connecticut’s environment and economy. The state’s shellfishing industry generates about $30 million annually and accounts for some 300 jobs, according to the state Department of Agriculture. More than 70,000 acres of shellfish farms are under cultivation in Long Island Sound alone, and shellfish account for about 70 percent of all Connecticut fisheries’ revenue, according to the agency.

Since 1998, when Connecticut’s lobster catch hit a record 3.7 million pounds, the numbers have dropped significantly. In 2013, the Nutmeg State lobster catch was 121,700 pounds, according to the Department of Agriculture.

Varying explanations have been theorized — overfishing, warming waters, pollution and habitat loss — but Connecticut isn’t alone when it comes to changing saltwater chemistry and adjusting populations of marine life.

The world’s oceans haven’t been able keep pace with increasing greenhouse-gas emissions. After decades of absorbing nearly a third of excess atmospheric carbon dioxide, the planet’s salt waters are suffering from acid reflux.

Acid sinks

While the shellfish that inhabit the region’s coastal waters are a popular part of southern New England’s social and cultural fabric, they also are integral pieces of a marine ecosystem that provides economic and recreational opportunities, and environmental benefits.

Southern New England has spent plenty of time and taxpayer money upgrading stormwater systems and better managing runoff. Shellfish, most notably oysters and mussels, are efficient at taking excess nitrogen, supplied by wastewater treatment facilities, agricultural operations and over-fertilized lawns, out of vital marine waters.

A 2004 study published in Science that involved analyzing 70,000 ocean samples taken worldwide in the 1990s found that 48 percent of carbon dioxide produced by human activity between 1800 and 1994 — 467 billion tons — had been absorbed by seawater.

The burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution has made the oceans, on average, 30 percent more acidic at the surface, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The world’s five oceans also absorb about 90 percent of the heat trapped by increasing levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

NOAA scientists have projected that the world’s oceans and coastal estuaries will become 150 percent more acidic by the end of the century.

Seawater is naturally alkaline, with a healthy pH that ranges from 7.8 to 8.5 (7 is neutral). But with a daily intake of some 22 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, these waters are losing the ability to handle the acid.

This change in seawater chemistry, caused by an increased concentration of hydrogen ions, also impacts the behavior of non-calcifying organisms. For example, the ability of certain fish to detect predators is decreased in more acidic waters, according to NOAA research.

When marine waters absorb carbon dioxide, carbonic acid — the same acid that gives soda its fizz — is formed. This acid dissolves the shells of mollusks, crustaceans and zooplankton, leaving the foundation of the marine food web vulnerable.

More carbon dioxide in the oceans means slower growth, thinner and more fragile shells, and poor shellfish reproduction, according to Newport, R.I.-based Sailors for the Sea. When excess carbonic acid is present, the formation of calcium carbonate becomes difficult and can dissolve shells that have already been formed.

The corrosion of shellfish caused by increased carbon dioxide in the water will reduce U.S. shellfish production 10 percent to 25 percent in the next five decades, according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI).

“The current rapid rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, due to our intensive burning of fossil fuels for energy, is fundamentally changing the chemistry of the sea,” Scott Doney, a WHOI senior scientist, wrote in testimony he presented to the House Committee on Science and Technology during a hearing in 2008 on the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act. “Acidification threatens a wide-range of marine organisms, from microscopic plankton and shellfish to massive coral reefs, as well as the food webs that depend upon these shell-forming species.”

During the past 250 years, atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased by nearly 40 percent, in large part because of fossil-fuel combustion and deforestation, according to Doney. In that time, the world’s oceans have absorbed some 525 billion tons of carbon dioxide.

Ocean acidification could also impact the millions of people who depend on the oceans for food and jobs. Fish and marine organisms provide, on average, 15 percent of the world’s protein. Americans alone spend about $60 billion annually on fish and shellfish. And reef losses would expose low-lying areas and biologically diverse regions to storm surge and wave damage.

More study needed

Shelley Brown, education director for Sailors for the Sea, testified last year at a House Committee on the Environment and Natural Resources hearing for a bill that would create a Rhode Island marine acidification study commission.

“Ocean acidification not only posses a serious threat to Rhode Island marine species and ecosystems, but also our economy,” Brown said.

In Rhode Island, this change in ocean chemistry could threaten the nearly 15,000 jobs in the state’s marine trades sector and $418 million in annual taxes and fees, said Brown, who holds a doctoral degree that focuses on microbial ecology in coastal marine environments from the University of Rhode Island.

The bill’s sponsor, Rep. John Edwards, D-Tiverton, noted that other states, such as Maine and Maryland, have set up similar study commissions. In Maine, where lobsters account for 80 percent of fishery revenue, there is considerable concern about the impact of acidification, he said.

“Rhode Island has a vibrant fishing economy and we want to make sure we keep that intact,” Edwards said.

URI oceanography professor Susanne Menden-Deuer testified at the hearing that creating a commission to study the available science and identify management strategies for Narragansett Bay is a good idea. She noted, however, that “it wouldn’t suffice to isolate the effect of ocean acidification but rather look at the multiple stressors that estuaries are subject to.”

She said it’s tricky to detect ocean acidification in estuaries, because the effects of runoff often appear as acidification.

Ocean Conservancy scientist Sarah Cooley said shellfish will experience the negative effects of ocean acidification first. Rhode Island is highly vulnerable because of the heavy harvest of oysters and quahogs, she said.

Cooley also said the Ocean State is vulnerable because Narragansett Bay experiences the negative effects of excess nutrients and runoff, which worsens ocean acidification. She said these challenges present opportunities to create tailored responses to acidification.

The bill was held for further study.

Impact on food web

A team of researchers from MIT and the University of Alabama has found that increased ocean acidification will dramatically affect global populations of phytoplankton — microorganisms on the ocean surface that make up the base of the marine food chain.

In a study published last July in the journal Nature Climate Change, the researchers reported that increased ocean acidification by 2100 will spur a range of responses in phytoplankton: some species will die out and others will flourish, changing the balance of plankton species worldwide.

The researchers also compared phytoplankton’s response not only to ocean acidification, but also to other projected drivers of climate change, such as warming temperatures. For instance, the team used a numerical model to see how phytoplankton as a whole will migrate significantly, with most populations shifting toward the poles as the planet warms. Based on global simulations, however, they found the most dramatic effects stemmed from ocean acidification.

Stephanie Dutkiewicz, a principal research scientist in MIT’s Center for Global Change Science, noted that while scientists have suspected ocean acidification might affect marine populations, the group’s results suggest a much larger upheaval of phytoplankton — and therefore probably the species that feed on them — than previously estimated.

“I was actually quite shocked by the results,” said Dutkiewicz, the paper’s lead author. “The fact that there are so many different possible changes, that different phytoplankton respond differently, means there might be some quite traumatic changes in the communities over the course of the 21st century. A whole rearrangement of the communities means something to both the food web further up, but also for things like cycling of carbon.”

Dutkiewicz also noted that shifting competition at the plankton level may have major ramifications further up the food chain.

ecoRI News staffer Tim Faulkner contributed to this report.