Wildlife Management to Boost Hunting Chokes Biodiversity, Ignores Climate Crisis

Rhode Island favors habitats popular with game species. The state instead needs a renewed commitment to stewarding the natural world in a manner that allows it to reduce the impacts of climate change and to preserve life.

November 30, 2023

“The conservation of biodiversity is among the most important missions of human society and should be a fundamental goal for management of both public and private land.”

This statement appears in the 1994 book “Saving Nature’s Legacy: Protecting and Restoring Biodiversity,” by Reed Noss and Alan Cooperrider. The book was designed to be a manual “to do what needs to be done to protect and restore the full spectrum of biodiversity in North America.”

Both authors had formerly been employed by federal land management agencies and realized the challenge of balancing traditional agency missions to manage for maximum yield of natural resources with the rising need to limit management to address the biodiversity crisis. Noss and Cooperrider recognized the sense of mission they shared had to be tempered with a pragmatic realization that internal changes in these agencies would be central to any advances in biodiversity conservation.

Nearly 30 years since the book’s publication, the internal changes that would be essential to biodiversity conservation haven’t materialized. In fact, the mission to preserve North American biodiversity has lost considerable ground.

The loss of biodiversity became a public issue with implementation of the 1993 U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), an international treaty that has been signed and ratified by every member state except the United States and the Holy See. President Clinton signed the CBD, but Republican lawmakers have continually blocked ratification, which requires a two-thirds Senate majority.

Signatories of the CBD are required to prepare a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plans that addresses the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity in each member state, but as a non-signatory the United States isn’t obligated to prepare such a document.

As recently as 2022, President Biden was petitioned by Democrats in Congress to sign a presidential order to prepare a National Biodiversity Strategy; however, there is a larger contingent of congresspersons, federal and state government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and universities that would be more than happy to never see such a document, because a national focus on biodiversity would require adopting new land management paradigms that focus on maintaining the integrity of natural ecosystems.

Such a focus is anathema to government natural resource agencies, because the extraction of resources requires the despoilment of natural ecosystems. Any limitations placed on resource extraction would be, in the view of corporate America, economically unsound. It’s simple: natural resources contribute to gross domestic product (GDP), biodiversity does not.

Reducing carbon emissions by curtailing the extraction and use of fossil fuels is a threat to the U.S. economy and GDP, or so says the fossil fuel industry and the army of climate deniers it supports. In response, government fails to enact appropriate regulations, continues to subsidize fossil fuel industries, and carbon emissions continue to rise.

Likewise, curbing the loss of biodiversity by curtailing the harvest of trees is viewed as an economic threat by the wood and wildlife industries. In response, government has failed to enact management policies on public lands that address biodiversity loss, has continued to implement management practices that diminish biodiversity, and has participated in a disinformation campaign to support these decisions.

A 2020 paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution warned in its title that “Biodiversity scientists must fight the creeping rise of extinction denial.” According to the paper, there are three categories of extinction denialism. The “literal denial” posits that species extinctions were mostly a historic problem and that the natural rate of extinctions has leveled off. The “interpretive denial” suggests that economic growth alone will fix the extinction crisis because pressures on the environment will eventually decrease with rising income levels.

The “implicatory denial” claims technological fixes and targeted conservation interventions will overcome extinction. This claim implies that human intervention with new technologies will solve the problems created by humans intervening in the functioning of natural systems. For example, foresters develop new harvesting strategies they say will create habitats preferred by certain declining wildlife species.

Wildlife vs. biodiversity

“Wildlife not only reflects the continent’s wealth but, in many respects, wildlife is that wealth.” So says the Wildlife Management Institute.

The wildlife industry is a significant contributor to GDP. The National Shooting Sports Foundation reports gun sales of more than $50 billion in 2023, and an additional $80 billion in economic impact associated with the manufacture, distribution, and sale of firearms. Although most guns sold are not for hunting, an excise tax collected on the sales of all firearms and ammunition is directed to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for dispersal to state wildlife agencies for conducting wildlife management. Disbursement amounts are based on the number of hunting licenses sold in each state.

The Wildlife Management Institute (WMI) is a nonprofit support organization for the wildlife industry, self-described as “typically working away from the public limelight to catalyze and facilitate strategies, actions, decisions and programs to benefit wildlife and wildlife values.” The board of directors includes representatives of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, Boone and Crockett Club, Pheasants Forever, and Wild Sheep Foundation.

The essential thing to know about the Washington, D.C.-based organization is encapsulated in the following paragraph that introduces the organization’s efforts in recruitment and retention:

“Hunters and recreational shooters collectively form a multi-billion-dollar industry and, as a result, have significant cultural and economic impacts in the United States. These two groups are also the foundation of financial support for state-level wildlife conservation efforts. However, since the 1980s, there has been a noticeable decline in participation in these activities posing a threat to wildlife conservation and the related outdoor industries.”

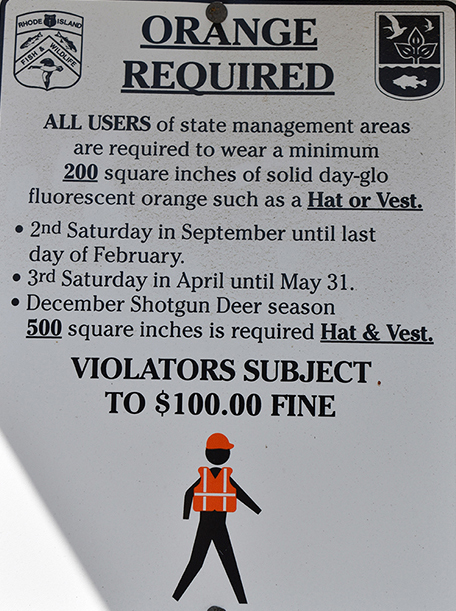

“Decline in participation” refers to the drop in the number of U.S. hunters from 17 million in 1980 to 11.3 million in 2016, as reported by the Fish & Wildlife Service. This decline is most noticeable in urban states like Rhode Island, where the number of hunting license holders in 2022 was fewer than 8,000.

A 2021 article from North Carolina State University noted that “for state wildlife agencies, the decline in hunting has stifled license sales and other forms of funding, leaving them inadequately staffed and unable to protect critical habitat and effectively implement management programs for deer and other animals.”

Although wildlife agencies and the WMI are working to recruit new hunters, retain old hunters, and reactivate those who have quit, these programs have generally failed to bring in new hunters.

The WMI has helped some state agencies with budget shortfalls by hiring contract employees for them. This link is a WMI job announcement for a wildlife biologist position in Rhode Island, one of several positions now staffed by WMI personnel that were formally staffed by state employees.

WMI employees come to Rhode Island to conduct the organization’s work, and a big part of their portfolio is the Young Forest Project, listed by the WMI as one of its most important accomplishments.

According to the Institute, “implementation of the Young Forest project has been successful in the Northeast, northern Appalachian Mountains, upper Great Lakes, lower Great Lakes and the mid-Atlantic Coast regions. The project involves more than 30 partners and is designed to meet habitat restoration goals identified in the American Woodcock Conservation Plan, New England Cottontail Conservation Strategy and Golden Winged Warbler Conservation Plan. Habitat restoration will also benefit ruffed grouse, white-tailed deer, moose, snowshoe hare, and 60 other species of wildlife in need of conservation.”

Young forest is simply another name for early successional habitat. For those unfamiliar with either term, take note of the white-tailed deer listed as a species in need of conservation. Many Rhode Islanders understand the deer population to be excessive in their state, to the point of being an issue of public safety. It should be apparent that there is plenty of habitat in Rhode Island to support a substantial deer population, yet wildlife agencies insist on conducting more and more habitat “improvement” projects that create more and more white-tailed deer habitat.

Young forest and early successional habitat are just new names for the kinds of wildlife habitat improvement projects that managers have been doing since the 1950s on state management areas, but in recent years these practices have been encouraged on properties owned by land trusts and other conservation NGOs, as well as on privately owned land.

It should be easy to understand that creating open, sparsely vegetated areas by clear-cutting tracts of forest is a highly destructive action that destroys a significant amount of biodiversity. Despite the obvious negative impacts, resource agencies insist on promoting these projects and objecting to any efforts that might limit their implementation.

The degree to which these objections have been made in Rhode Island reached a particularly concerning level during the recent legislative effort to protect old-growth forests. The Old Growth Forest Protection Act (H7066) was first proposed in the House during the 2022 General Assembly session and was eventually held over for further study, primarily because of objections by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

The agency stated in written testimony that passage of the act would “inhibit DEM’s ability to effectively manage forests located on state property in a manner that benefits wildlife, recreational users, and the overall health of our forest ecosystem.” The state agency suggested that the newly established Forest Conservation Commission “be given the opportunity to study the issue of old growth forests and to make appropriate recommendations regarding their protection.”

However, when the Old Growth Protection Act was reintroduced in the 2023 session (H5344), DEM did not offer recommendations. Instead, the agency noted “the definitions for several terms used in the bill, including ‘forest’ and ‘old growth forest’ are inconsistent with the current forest science consensus. Additionally, the techniques that the bill proposes for identification of old-growth forest, such as tree coring and soil sampling, are not necessary to determine if a forest displays characteristics of old-growth forest. Neither the age of an individual tree or group of trees nor soil characteristics in a forest are what defines an old-growth forest.”

DEM also began a campaign to discredit the proposed act with a technical commentary. The tone of this commentary is entirely negative. There are no suggestions for improvements to the bill, no offerings of assistance in defining old-growth forests, or identifying where they are on the Rhode Island landscape, and no recognition of the importance of old-growth forests in supporting biodiversity.

Instead, every attempt is made to downplay the importance of old growth, to dispute the need for H5344, and is a clear message from DEM that the agency has no interest in protecting old-growth forests.

Apparently, DEM is so adamantly opposed to H5344 that it disputes the provisions of the bill with disinformation, turning the science of conservation biology upside down. For example, H5344 states as a point of fact that there are certain animals, insects, and birds that only live in old-growth forests.

In response, DEM states this is factually incorrect. There are no known old-growth specialist species in New England.

The agency’s response is wrong. There are several well-known specialists in New England’s old-growth forests representing several taxonomic groups including mammals, birds, plants, lichens, fungi, beetles, and a host of other arthropods. Even in Rhode Island, yes, there is old growth. The best example is a 200-plus-acre red maple swamp in Charlestown with 200-year-old trees that is the only New England nesting site for the prothonotary warbler, a recognized old-growth specialist at the northern edge of its breeding range.

DEM adds that, in fact, while mature forest species in New England tend to be generalists, early successional and young-forest species are often habitat specialists. Many early successional and young-forest species that were once abundant in pre-colonial southern New England are now in decline or have disappeared completely, according to DEM.

Mention of “early successional” and “young forest” is superfluous to a discussion of old-growth protection and is indicative of DEM’s paranoia about any limitations on what they do, even to the point of spinning a false narrative.

To start, early successional species were never abundant in the pre-colonial forests of southern New England. During that period of peak forestation, species that managers label today “early successional” would have been found in natural habitats near the coast, such as salt marshes, dunes, and maritime shrublands. Some of these species occasionally took advantage of actual early successional habitats that were created within upland forests by windstorms and other natural disturbances, but these events were quite rare.

With European colonization, early successional habitat exploded as the forest was eliminated for wood products and fuel and the open land became farmland, pasture, and habitat for a group of opportunistic species we call generalists because of the wide range of habitat conditions they occupy. Today, there are many modern-day human-created habitats that have been adopted by early successional species, including thousands of acres of powerline and pipeline rights of way.

The treatment of early successional species as habitat specialists is indicative of a problem that proponents of this management action have in trying to explain the value and purpose of what they do. Managers claim that creation of early successional habitat (ESH) is necessary to enhance populations of imperiled or vulnerable species, but no such species have been identified. Even the American woodcock, which serves as the poster species for ESH proponents, has been shown to be secure and in little need of conservation action.

However, where the DEM argument really loses credibility is the realization that a major beneficiary of ESH creation is the white-tailed deer, which could be defined as the perfect generalist.

The dearth of early successional species that actually need conservation attention has forced managers to invent some. For example, the Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan identifies the gray catbird as a species of greatest conservation need, because the gray catbird “utilizes shrub thickets that are important to many other nesting species and birds during migration, this is a useful umbrella species with which to track the condition of this habitat type.”

The newly published Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in Rhode Island describes the catbird as “a familiar sight in Rhode Island … one of the state’s most abundant breeding birds … estimated statewide population of >360,900.”

With such impressive numbers, why is the catbird considered a species needing conservation attention?

One answer is that listing the gray catbird in Rhode Island, the only state other than Alabama to do so, allows the Wildlife Management Institute to include this bird in its publication Under Cover: Wildlife of Shrublands and Young Forest. This booklet identifies “65 birds, mammals, and reptiles identified as species of greatest conservation need that depend on young forest or shrubland for their continued existence — habitats that have steadily dwindled over the past century.”

It is difficult to give much credence to a conservation plan that highlights an abundant species, suggesting its habitat has dwindled. The fact is, habitat for the gray catbird is plentiful, and listing this bird is simply a convenience to support management actions that diminish biodiversity. As stated in “Under Cover,” “gray catbirds will breed within clearcuts once dense, woody vegetation has regenerated.”

The University chimes in

The DEM technical commentary was prepared by the agency’s forest stewardship program coordinator, Fern Graves. Curiously, the document wasn’t attached to DEM’s H5344 objection letter, which was submitted to the House Committee on Environment and Natural Resources on March 9.

Apparently, the commentary was prepared to convince the state’s environmental community to not support the bill, as when Graves appeared before the regular monthly meeting of the Environment Council of Rhode Island on April 3. (ECRI eventually decided to not support H5344.)

However, another piece of testimony submitted in objection to H5344 was a Feb. 15 letter from Christopher Thawley, a University of Rhode Island assistant professor, that repeated some of the same false claims as the DEM technical commentary. It noted, for example, that “there are no known animal species in Rhode Island (or even New England!) which are shown to require old growth forests for their survival.”

Thawley discussed at length how prohibiting management of old-growth forests is “an outcome which could endanger public safety and property.” He claimed “the bill would actively restrict, exclude, or prevent some types of management on many lands, including managing for wildfire prevention and mitigation, improving water quality, and wildlife habitat. … These prohibitions would effectively bar responses to ongoing wildfires and even timely preventative measures. Loss of life and property could result from these prohibitions [along with] loss of habitat for vulnerable wildlife, reduced water quality, and buildup of fuel material leading to increased wildfire risk, a pattern we are currently seeing across the US.”

Why is the issue of life-threatening wildfire raised in objection to an old-growth forest protection bill? New England forests are much less prone to destructive wildfire than other regions of the country where fuel buildup is a contributing factor. Moreover, protecting old growth is a much better strategy for reducing fire risk.

Disinformation campaigns typically rely on a fair amount of hyperbole, exaggerated claims using words intended to shock the reader — “loss of life and property,” “loss of vulnerable wildlife,” “reduced water quality.” It is astonishing to see these phrases used in objection to old-growth protection when this forest age class is more effective in protecting vulnerable wildlife, improving water quality, and reducing the risk of fire.

Thawley also complained that H5344 will restrict DEM’s ability to manage the state’s forests. It is certainly true that the management of Rhode Island’s public forestlands needs serious attention by the General Assembly in response to the biodiversity and climate crises; however, the intent of the bill is to restrict management in a few special places that can serve as touchstones for what Rhode Island once was. It is not a restriction on DEM’s management of the majority of the state’s 40,000 acres of forest.

Thawley also shared an interesting assessment of the capabilities of volunteer, non-governmental personnel to identify old-growth forests. In his opinion, the “tree coring, identification surveys, and soil sampling require extensive training and person-hours to conduct correctly so that resultant data is interpretable. Simply providing unspecified materials to local governmental organizations to engage in this specialized work without additional financial support and hiring of appropriately trained personnel will not yield quality results.”

It is unfortunate that as a newcomer to Rhode Island, Thawley is apparently unfamiliar with projects supported by URI that rely on significant support from trained volunteers. Notable programs include Watershed Watch, Breeding Bird Atlas, Invasive Plant Atlas of New England, and New England Plant Conservation Program.

Again, the tone of Thawley’s letter is not one of cooperation that should be expected from a university professor, which is quite puzzling considering his stated belief “that identifying and protecting old growth forests is a valuable goal.”

Biodiversity, climate, and government

State legislatures throughout the country are struggling with how to address the climate and biodiversity crises. As they go about their business, these assemblies of mostly nonscientists must have access to the latest science concerning two basic strategies for addressing these issues: mitigation and adaptation.

Mitigation is recognizing what is currently available that can help lessen an impact. For example, carbon emitted into the atmosphere can be mitigated by forests that sequester and store the greenhouse gas. Advice concerning climate mitigation in Rhode Island was provided by the Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) in its 2016 Rhode Island Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Plan, in a section titled “The Mitigation Option.”

“Land use conservation strategies preserve natural systems and environments that provide carbon dioxide ‘sinks,’ helping to reduce the state’s net [greenhouse gas] footprint,” according to the 89-page document. “Strategies include protecting existing forest acreage, reforestation, conservation of riparian buffers, enhanced forest management programs, reductions in soil erosion to minimize losses in soil carbon storage, coastal wetland protection, and enhanced urban tree canopies.”

The plan also noted that “Existing programs like the Forest Legacy Program, the Forest Stewardship Program, and Urban and Community Forestry help reduce those pressures and allow forest land to be preserved and utilized to be a carbon sink. Continued public support for funding open space protection continues to be a critical component of the State’s land protection efforts.”

Rhode Island has a long history of conserving land to preserve natural systems, but most state-owned properties were acquired and are managed for wood and wildlife. It is not surprising to see the EC4 suggest that “enhanced forest management” is a viable mitigation tool since the chair of the council is the director of DEM, the same agency that cringes at any attempt to limit its management of the state’s forests. The lesson here is that no land acquired by a conservation entity in Rhode Island guarantees it will be protected for its natural values unless there are enforced legal restrictions.

If forest ecosystems are to effectively preserve biodiversity and mitigate the impacts of climate change, then forests must remain intact. The EC4 doesn’t recognize this reality. Instead, it points to existing U.S. Forest Service programs that reward private landowners for maintaining “working forests,” farcically suggesting that enhanced management will improve a forest’s ability to be a carbon sink.

There is no EC4 for the biodiversity crisis. There is no Rhode Island biodiversity action plan. There is in fact no recognition by Rhode Island government that a biodiversity crisis exists. Maybe it’s because people are just tired of being told they are responsible for another bad thing happening in the world, but the general public apathy about biodiversity has allowed the wood and wildlife interests to convince everyone their methods are a solution, when in fact they are exacerbating the problem.

A solution to this problem is for the state to adopt a policy of pro-forestation in which existing intact forests are allowed to grow to their full ecological potential. According to the proponents of this stewardship action, pro-forestation serves the greatest public good by maximizing co-benefits such as nature-based biological carbon sequestration and unparalleled ecosystem services such as biodiversity enhancement, water and air quality, flood and erosion control, public health benefits, low-impact recreation, and scenic beauty.

It serves the greatest public good. Is this not the primary function of government? To legislate and develop policies that serve the greatest good. How bad does it have to get before government understands that unpopular actions will be necessary to solve the existential crises of our time, climate change and biodiversity loss? How catastrophic do storms and floods need to be? How many more species need to be lost?

A call for biodiversity action

The state of Rhode Island needs to officially recognize the biodiversity crisis and pledge to do its part in addressing this issue with the following actions:

Prepare an updated biodiversity protection strategy. From 1978-2007, the Rhode Island Natural Heritage Program (NHP) inventoried the state’s biodiversity and identified priority sites for protecting natural ecosystems and rare species. Many of these sites were eventually protected with the assistance of open space grants provided by voter-approved referenda.

In addition, the NHP reviewed the required management plans of all properties acquired with open space funds to ensure biodiversity elements would be protected.

An updated biodiversity strategy would require reestablishing a Natural Heritage Program, or similar initiative, that should be situated in a state office other than DEM, to reduce the natural resource bias and provide a balanced approach to how state-owned lands are managed. Management plans should be written for all state-owned properties through a transparent, publicly reviewed process.

Reform the state current use program. Forest landowners in Rhode Island can seek property tax relief through the state’s Farm, Forest, and Open Space program, which allows land to be assessed at its current use value, rather than its development value. To qualify, a property must be a minimum 10 acres, and “the forest must be actively managed in accordance with the provisions of a written stewardship plan for the purpose of enhancing forest resources.”

Today’s forest landowners are besieged by government agencies and NGOs that provide money and expertise for harvesting trees to enhance wildlife habitat. The Natural Resource Conservation Service, Fish & Wildlife Service, and Forest Service provide the money, and nonprofits like The Nature Conservancy and Audubon provide on-the-ground support. In the southern part of the state, landowners can agree to manage their forests as part of the Great Thicket National Wildlife Refuge.

But what about forest landowners who want to keep their forest intact? Carbon sequestration and storage and biodiversity should be included in “stewardship plans” as forest resources that can be enhanced by doing nothing more than leaving a forest intact. Landowners should not be penalized for adopting pro-forestation.

Bring accountability to the work of state managers. In Vermont, state land managers are required by law to develop binding rules for what is and isn’t appropriate on state lands, balancing management goals to protect climate, public health, and biodiversity. As noted by proponents of this law, “without accountability and transparency, state land management is an open-ended adventure in executive privilege, removing the ‘public’ from public lands. State agencies can cut trees, build damaging roads, and amend management plans with impunity.”

Rhode Island managers are not required by law to develop binding rules that balance management goals to protect climate, public health, and biodiversity. They are accountable only to the federal agencies (Fish & Wildlife Service and Forest Service) that fund them, do not have management plans for state lands, and conduct logging, road building, bridge construction, and wetland alterations on those lands with little oversight.

DEM will argue that its natural resource managers are accountable for their actions as they are outlined in the State Wildlife Action Plan. As reported in the 2016 EC4 Annual Report: “RIDEM — with the assistance of the RI Chapter of The Nature Conservancy and the University of Rhode Island — was one of the first states to forge ahead towards a revision of its State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP), which aims to: reassess priority species/habitats, and provide more detailed mapping of priority conservation areas; analyze threats affecting fish and wildlife, including those posed from habitat loss, degradation, population growth, and climate change; outline a number of conservation actions to address or alleviate threats and help effectively conserve Rhode Island’s valuable wildlife resources.”

The state’s Wildlife Action Plan is not a biodiversity plan. It is a document required by the Fish & Wildlife Service to qualify for funding through the federal agency’s State Wildlife Grant Program. Its citation in the EC4’s 2016 Annual Report is dubious because the SWAP provides few recommendations for addressing the climate and biodiversity crises. There is no discussion of mitigation, and much of the talk about adaptation refers to creation of habitats predicted to be impacted by climate change, including early successional types.

The most important function of the SWAP is defining the list of species of greatest conservation need (SGCN), which identifies those species eligible for wildlife grant funding. Unlike lists of rare and endangered species that are based on biological criteria, SGCN lists also include species that are not necessarily in need of conservation action, such as the gray catbird.

Clearly, the inclusion of common, secure species in an official list of species needing conservation action raises credibility issues with the SWAP. Recognition of the SWAP by the EC4, when it has no relevance to the climate crisis, is just a weak attempt to give DEM, URI, and TNC more credit than they deserve in addressing the climate crisis.

The deer problem. There are many people who have come to think of white-tailed deer as an invasive species. Lyme disease, traffic accidents, and foraging in suburban and urban neighborhoods are some of the familiar problems. Deer are also a significant factor in forest ecosystems as foragers of regenerating trees, shrubs, and ground vegetation. They have been implicated in the demise of several native plants in Rhode Island, including painted trillium and yellow lady’s slipper.

DEM’s Division of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) has consistently refused to consider any method of controlling the state’s overabundant deer population other than regulated hunting. This should not be surprising given its association with the Wildlife Management Institute, which believes creating more young forest to support more deer is a fine thing to do.

This situation requires legislative action, at a minimum the creation of a study commission to investigate the various deer control options and how the DFW currently conducts deer management to determine what legislation is needed to address the state’s overabundant deer population.

Natural areas protection. In 1993, the Rhode Island Natural Areas Protection Act (NAPA) was passed with support of TNC to provide “the highest level of protection to the state’s most environmentally sensitive natural areas.” Under this law, potential natural areas would be evaluated by the Natural Heritage Preservation Commission, with advice of the Natural Heritage Program, and sent to the DEM director for official designation.

Following passage of the act, several natural areas on state land were recommended for designation, but 30 years later there are no records on file at DEM or TNC about these designations, or anything regarding implementation of the NAPA. It is important to note that there would be no need for an Old Growth Forest Protection Act if the NAPA was functioning as envisioned. Reestablishing the Natural Heritage Program would provide the expertise to identify old-growth forests and other unique biological and geological features as protected natural areas.

The keynote speaker at the 2017 Rhode Island Land & Water Conservation Summit was Dr. Eric Chivian, co-editor of the book “Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity.” The essential message of the book is that “human health depends, to a larger extent than we might imagine, on the health of other species and on the healthy functioning of natural systems. The greater we understand and more rationally manage our relationship to the rest of life, the greater the guarantee of our own safety and quality of life.”

Natural systems can’t function properly when they are constantly being altered to provide resources for the economic benefit of humans. If Rhode Island’s biodiversity is to be sustained, the state’s resource managers must stop following their inane policy of creating more habitat for wildlife that doesn’t need it.

There also must be a renewed commitment to stewarding natural ecosystems in a manner that allows them to perform the ecological functions necessary to reduce the impacts of climate change and preserve biodiversity.

Rick Enser served for 28 years as the coordinator of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Natural Heritage Program before retiring in 2007. The now-defunct state program documented the Ocean State’s biodiversity and provided guidance for the preservation of rare and endangered species. He now lives in Vermont.

This is excellent writing and thorough. Thank you Rick!

Very informative and well written. All RIers concerned with our State’s natural systems and biodiversity should read this!

Thank you Mr. Enser.

Excellent opinion piece. I continue to be amazed at the folly of humans to think they can “manage” the natural world better than ultimate life-sustaining systems that millions of years of evolution has produced. As Mr. Enser points out, allowing forests to achieve the full “ecological potential” should be the aim which would allow for a plethora of benefits for all life (including humans). Imagine that as a society we embraced such an ethic across the board. How wonderful that would be.