Tick-Borne Alpha-Gal Syndrome Becomes More Common in Region as Lone Star Ticks Move In

April 11, 2024

Cliff Vanover knew something was wrong one night while traveling in upstate New York in 1995. His palms got itchy, then he got hives, then “my body was one solid hive,” he said. He had gone into anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction.

His wife had antihistamines for her own allergies, so he took some and the symptoms subsided. But then it happened again. “I had no allergies at the time,” Vanover said, so he went to an allergist, who did a series of scratch tests. The Charlestown, R.I., resident learned he was allergic to beef, lamb, and pork.

Although there was no name for it three decades ago, when Vanover contracted it, he had what is now known as alpha-gal syndrome. It’s caused by the bite of a lone star tick, and it’s going to become a lot more prevalent here in New England.

Tick migration

Thomas Mather is a professor of plant sciences and entomology and is the director of the University of Rhode Island’s Center for Vector-Borne Disease and its TickEncounter Resource Center. He oversees TickSpotters, a site that educates the public about ticks and encourages people, when bitten by a tick, to submit a photo of it to the site so the tick can be identified.

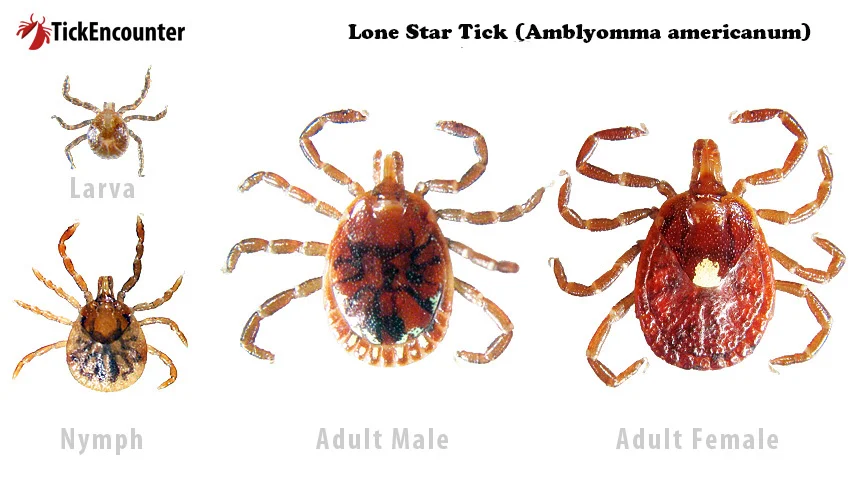

Since he has begun tracking ticks in Rhode Island, Mather said, the reports of lone star ticks increased by 300% between 1999 and 2023. Previously, they were thought to be a mostly southern tick.

“In 1992, we started a black-legged tick survey,” he said. “Every once in a while, we’d find [a lone star tick], but it was explainable. Six to seven years ago we started seeing them on a regular basis.”

The ticks were common on Prudence Island, he said, but were never really established elsewhere in Rhode Island. Now, he said, they are the main tick species in Jamestown. “We go over there and we can find them anyplace we stop on [Conanicut] Island,” he said.

That’s because, he said, lone star ticks prefer to feed on white-tailed deer, and also use them as reproductive hosts. “In black-legged ticks, only the adults feed on deer, but all three stages of lone star ticks feed on deer,” he said. “It’s hard to get a lone star tick to bite a rodent.”

Since deer can swim from Prudence Island to Conanicut Island, so too can lone star ticks. In previous tick surveys, Mather said, lone star ticks were found in 11 Rhode Island zip codes. A more recent survey, he said, found them in nearly 30 zip codes.

Mather said that while lone star ticks were previously considered a southern tick, naturalists in the 1700s recorded them as far north as Albany, N.Y. He said their return to the Northeast is a direct result of the reproductive success of white-tailed deer.

“Dog ticks don’t feed on deer, and they haven’t changed distribution,” he said.

All of the ticks that have changed patterns in the past 40 years — black-legged ticks have increased in both the North and the South; lone star ticks moving north — depend on white-tailed deer for their reproductive success.

The name comes from the distinctive white mark on the backs of female lone star ticks. Mather said this species of tick is much more aggressive when they find a host.

“They can be in swarms,” he said. “When they get on you, they move very fast. When they latch onto your clothing, they will be underneath your shirt before you have a chance to see them.”

While black-legged ticks “saunter,” he said, lone star ticks are speedy.

Mather encouraged anyone bitten by a tick to take a picture of it. The TickSpotters website will get back to someone who submits a photo of tick within 24 hours.

“Don’t just throw the tick away,” he said. Different ticks transmit different germs. Find out what type of tick made the bite, and then start tracking health concerns from there, he said.

“It pays to know what kind of tick it is,” he said.

Alpha-gal syndrome

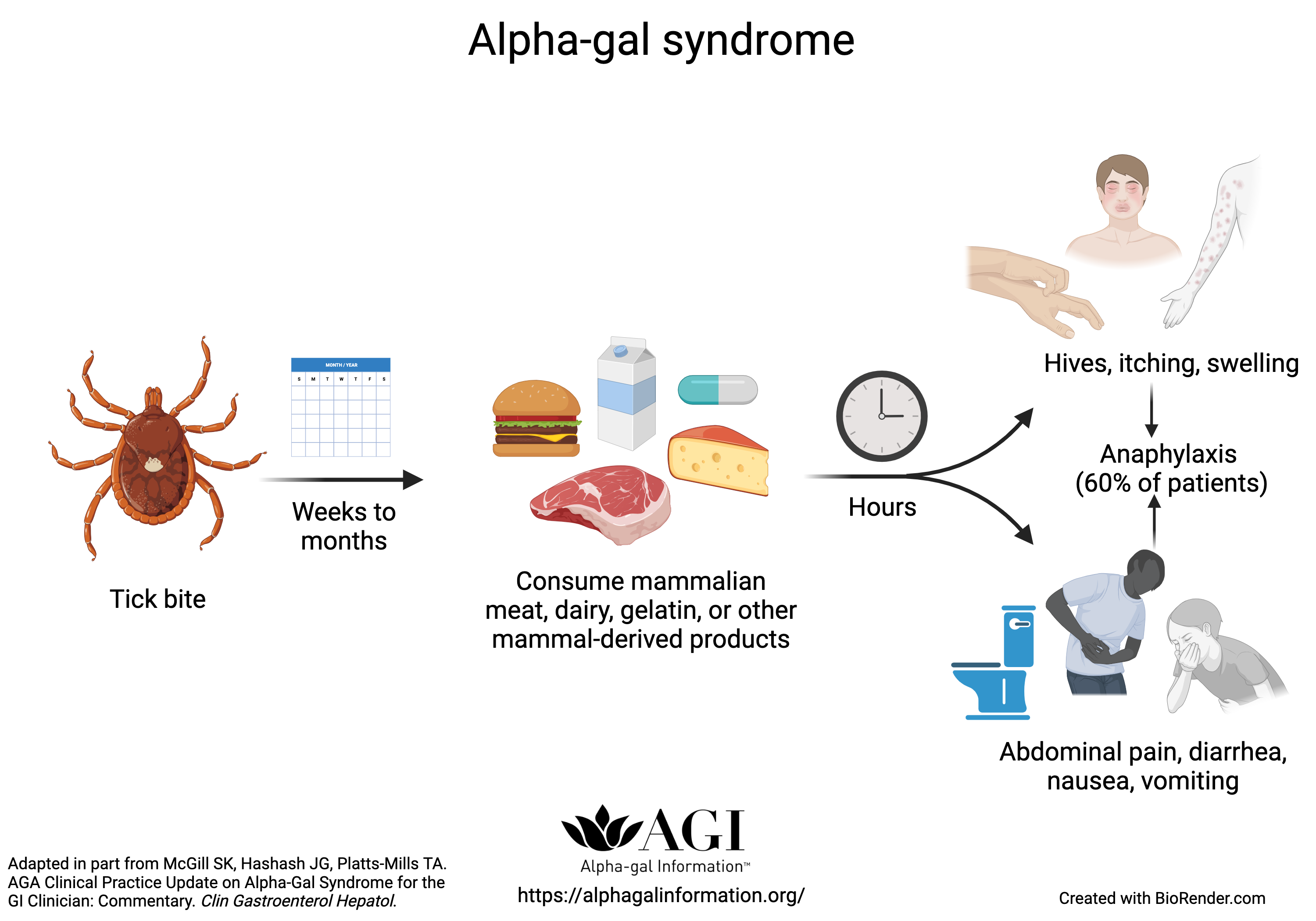

The bite of the lone star tick causes alpha-gal syndrome (AGS), an allergy to alpha-gal (AG), a sugar found in the tissues of all mammals except humans and other primates. The tick can have alpha-gal in its gut or saliva and transfer it to humans via a bite, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This can trigger an individual’s immune system to respond by producing antibodies against alpha-gal, a reaction called sensitization, since the immune system is now sensitive to alpha-gal. When a person sensitized to alpha-gal consumes or is exposed to alpha-gal again — for instance, by eating red meat, lamb or pork — the antibodies bind to the alpha-gal, which, in turn, prompts the immune system to release chemicals that cause an allergic reaction.

Symptoms range from the hives and anaphylaxis that Vanover suffered, to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Symptoms occur between three and six hours after eating.

Alpha-gal is also found in foods, medications, and medical products made from mammals. Dairy products contain AG, as do medications made from gelatin derived from mammalian collagen. It’s also found in prosthetic heart valves taken from cows or pigs. People with AGS have varying allergic reactions to these foods or medicines, with some people not experiencing any reaction, while others may be severe, according to the CDC. People with AGS can continue to eat chicken, turkey, fish, and other non-mammalian meats because those meats do not contain alpha-gal.

According to the website alphagalinformation.org, more than 20,000 drugs, vaccines, and medicines contain mammalian byproducts that could trigger AGS. According to the site, AGS is the No. 1 trigger of anaphylaxis in adults in areas where the lone star tick is prevalent, and is also the No. 1 cause of adult-onset food allergies.

Up to 450,000 U.S. residents have AGS, according to the CDC.

Cutting-edge research

In addition to tracking the location of lone star ticks, Mather is working with a team that includes scientists from the CDC, the University of Massachusetts, and Martha’s Vineyard to help develop an action plan for AGS, from the moment of the tick bite to treatment of the syndrome.

“Once someone uses a tool like TickSpotters, sends us a picture of a lone star tick, we can get them a serum within 72 hours before they develop an antibody” to AGS, Mather said. “We can then follow up four weeks later with a second test to see if they have AG antibodies. We have them fill out a questionnaire with a range of symptoms, and we’re able to include their doctor.”

That’s important, he said, because in a recent survey of health care providers by the CDC, about 75% of providers said they either didn’t know of or wouldn’t be able to diagnose AGS.

“It was alarming,” Mather said of the survey.

Mather said the team studying AGS is “working at the nexus of the front line of the invasion of this tick” in the region. While the tick is well-established farther south, including on the east end of Long Island, N.Y., it’s not common here yet.

“The east end of Long Island is completely infested,” he said. “Hospitals there see 900 patients” with AGS symptoms a year.

“But medical professionals in our area are unfamiliar with AGS,” Mather added.

To confirm a diagnosis, a doctor may order blood tests to check for the presence of antibodies against alpha-gal and/or against specific types of meat, such as beef or pork. But because of medical providers’ unfamiliarity with the syndrome, it can take up to seven years for a diagnosis of AGS.

Before it had a name

It took 10 years for Vanover to receive an actual diagnosis of AGS, he said.

Unlike some with AGS, Vanover can eat dairy products, he said. And, he said, he’s met people with AGS who didn’t know that was what they had. “There was a time when no one knew about alpha-gal,” he said. “But now more people are hearing of the disease.”

An avid outdoorsman, Vanover said he often gets bitten by ticks. “I’m really sensitive to them. Usually, I can feel them biting me. They don’t have a chance to be attached very long.”

He doesn’t know when or where he got bit in 1995 when the AGS symptoms started. He believes it was sometime before he went to New York.

“I had it long before there was a name for it,” Vanover said. “When it was determined that it was a syndrome, that’s when I learned what I had.”

To listen to a RadioLab podcast about AGS, click here.

For more information on alpha-gal syndrome, click here and here.

Strong detailed article about a risk most people are unaware of. Apparently linked to deer movement and migration rather than climate change expanding the habitat of this type of tick?

As for people developing allergies to meat or pork, that would be an ironic gain for the planet.

The lone star ticks have been north for a while. I lived in the Adirondacks and one of my colleagues has been doing tick-related disease research for years; my husband brought her a tick he’d found (on him) and she said immediately, “I didn’t realize the lone star ticks had gotten this far.” I’m glad to know that the tick and AGS are finally being thoroughly investigated.