Right to Repair Movement Demands Parts, Diagnostics, Access from Manufacturers

Information would allow individuals and independent repair shops to fix devices

June 29, 2023

Most Americans younger than 40 have never witnessed a live-action example of a shade-tree mechanic: a guy in a driveway or at curbside leaning low beneath the open hood of a car, wrenches and parts spread across the pavement, tinkering with the guts of his vehicle to get it up and running.

Since the early 1980s, when computer systems began to take over the operation of cars, the shade-tree mechanic has faded away as a cultural icon; car repair is now mostly in the hands of professionals.

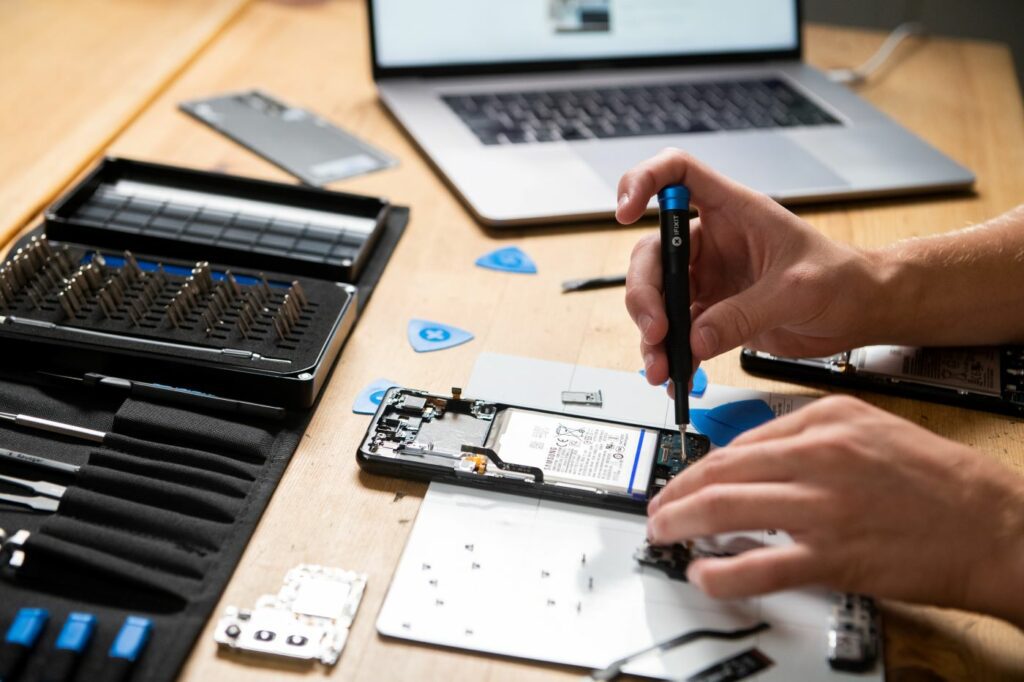

But a nationwide group of activists in the right to repair movement wants to turn back the clock for many other consumer products. They aim to force manufacturers to give consumers access to the parts, tools, diagnostic information, and software codes that would allow individuals and independent repair shops to fix many devices, such as cell phones, laptops, computers, drones, cameras, power wheelchairs, and farm equipment.

Right to repair proponents say some manufacturers — two major offenders being Apple and John Deere — hold an unfair and unnecessary monopoly on repairs. This allows original equipment manufacturers to restrict access to parts and information only to their contractually authorized dealerships. This often, in turn, drives consumers to throw away electronic devices with small problems, like a defunct battery, that could be fixed at home or in a small shop, and to buy new ones instead.

The pattern affects the environment because fixable electronic devices, which suck up a lot of natural resources simply to build and bring to market, land on the trash heap or, at best, in recycling systems, to the tune of an estimated 50 million tons a year, worldwide.

Interestingly, the movement gets much of its drive from farmers in the big Midwestern agricultural states who are enraged — no exaggeration — that they cannot get access to parts and software codes to make basic repairs to their expensive John Deere tractors.

In fact, Rhode Island’s first and unsuccessful attempt at a right to repair bill, in 2022, was initiated by complaints from a Lincoln farmer who couldn’t get a quick and basic repair done to his John Deere tractor.

At least 30 R2R bills have been filed in Congress and state legislatures in just the past two years. R2R laws have passed successfully in Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and New York since 2020.

What is it and why it is needed

Along with farmers who want to be able to fix their tractors, the R2R movement is being driven by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) and its state affiliates; Green Century Funds, a mutual fund that pushes for eco-friendly practices by corporations; and several up-by-the-bootstraps businesses such as iFixit that are figuring out ways to find parts and fix electronics through a kind of communal cowboy DIY movement.

Nathan Proctor, senior director of the Campaign for Right to Repair for U.S. PIRG, said the goal of R2R is to create a “robust competitive repair ecosystem of small appliance and repair shops similar to 30 years ago. People should have a full slate of options to keep the things they own going.”

He called the current system of manufacturers controlling access to parts and information — often through dealerships where staffing and training may be weak — a “captured” economic system. “This is a toxic economic condition in which you have a necessary thing, you have a monopoly over it, and you can charge whatever you want” for access, Proctor said.

Using a farm tractor as an example, he said something as simple as a turn signal “talks” to the machine’s main computer. To repair a turn signal, you have to put in a physical part and then update the computer to connect to it. Without access to the software, it cannot be done.

“It is like if you bought a computer and had to pay HP to drive to your house and install the driver at a cost of $1,100,” Proctor said.

Depending on authorized dealerships for repairs can be dicey. Proctor said he talked to an Apple dealership in Washington that had to pay $25,00 to join Apple’s repair program, but the dealer still did not get access to all repair options. The system for authorized repairs shops “seems specifically designed not to work,” Proctor said.

Overall, he said, when any manufacturer “restricts access to things needed to do repairs, authorized agents can overcharge you.”

Who opposes and why

Why do equipment manufacturers oppose R2R?

The sale of new products to replace dead but repairable devices creates profits. Also, dealership repairs are a profit center for manufacturers. No one throws away a $150,000 tractor, but people routinely will toss a cell phone and buy a new one because of a dead battery.

John Deere’s control over the repair market “is the backbone of its financial success,” with sales of its repair services “three to six times more profitable than its sales of equipment,” according to a complaint the National Farmers Union filed in early 2022 with the Federal Trade Commission.

Andrea Ranger is a shareholder advocate for Green Century Funds. “Over time, capital from sales doesn’t go far, but the repair business is steady income and lucrative for Deere,” she said.

An essay by the Competitive Enterprise Institute lists manufacturer objections to R2R. One item plainly names the fear of losing income from dealership repair services. R2R laws are “expected to cut into manufacturers’ profits by decreasing revenues from their own repair services and lowering the volume of new units sold.”

That could lead to higher prices for new goods, according to the essay. “One should expect manufacturers to raise prices on consumers to account for this profit loss.”

Manufacturers have many more arguments against R2R apart from direct profits. John Deere Co. claims that if farmers were able to open software that operates a tractor and monkey around inside it, they might alter emissions limits and thereby violate Environmental Protection Agency rules, for which Deere could be held liable. (R2R advocates say Deere would face no liability in such a case.)

Manufacturers fear problems over data security, cybersecurity, and trade secrets. The Competitive Enterprise Institute essay said forcing manufacturers to “release embedded software and security patches to independent repair providers … could compromise the cyber security of electronic equipment connected to an IP network.”

R2Rs could “chill innovation” and force makers to standardize their products because they could “persuade some manufacturers not to digitize some products in order to avoid having to comply with the law,” the essay declared.

Some standard arguments against R2R have been heard in the Rhode Island Statehouse, where an R2R bill, H7535, was introduced in 2022 by Rep. Mary Ann Shallcross-Smith, D-Lincoln. The bill would have provided “that original equipment manufacturers of agricultural equipment would provide independent service providers repair information and tools to maintain and repair electronics of the agricultural equipment.”

A statement opposing the bill from the Association of Equipment Manufacturers said, “There is a difference between consumers seeking to repair their own equipment — which they can do today — and those who seek access to the source code or operating software so they can circumvent safety and emissions standards or access proprietary intellectual property.”

The association, at the time, also declared, “These machines run as a system; when something is changed, it has cascading impacts down the line. For example, if a farmer wants to increase the horsepower of his or her tractor, the emissions also increase, bringing the machine out of compliance with the Clean Air Act.”

Right to repair fights back

R2R supporters are not shy about pushing back.

In testimony over Rhode Island’s R2R bill in 2022, the Rhode Island Farm Bureau directly contradicted one of the opposition’s claims about possible violations to air pollution laws, writing that the bill “is asking for the right to maintain, diagnose, and repair machinery that results in the machine being returned to its original specifications. It specifically excludes … any activities that result in the machine being modified outside of the original equipment manufacturer specifications.”

Dean Lees, a Rhode Island farmer whose prolonged and expensive effort to get his farm tractor fixed in the winter of 2021-2022 (when he needed it for snow plowing) said lobbyists and lawyers against the bill deliberately misconstrued one sentence to imply that the bill would drive parts and repair shops out of business.

The original wording defined “part” as supplied by “original equipment manufacturers.” After parts suppliers cascaded into a frenzy of worry over losing their businesses, the wording was changed to “original equipment manufacturers; implemented by or with surrogate distributors.”

On a broader front, R2R has an ally in the White House. In July 2021, President Joe Biden issued an Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, which included 72 initiatives. Among them was “Make it easier and cheaper to repair items you own by limiting manufacturers from barring self-repairs or third-party repairs of their products.”

In May 2021 the Federal Trade Commission issued its report “Nixing the Fix: An FTC Report to Congress on Repair Restrictions.” The report refers to the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, a federal law that governs warranties on consumer products, and asserts that the act “bars manufacturers from using access to warranty coverage as a way of obstructing consumers’ ability to have their consumer products maintained or repaired using third-party replacement parts and independent repair shops.”

The report lists eight specific techniques that manufacturers use to restrict repairs by consumers and notes “there is scant evidence to support manufacturers’ justifications for repair restrictions.”

The FTC also declared its readiness to support R2R legislation: “In addition to the FTC’s pursuit of efforts under its authority, the Commission stands ready to work with legislators … to ensure that consumers and independent repair shops have appropriate access to replacement parts, instructions, and diagnostic software.”

Headway

R2R advocates are gaining a bit of traction, in state legislatures and through other methods.

Green Century Fund filed shareholder proposals in 2021 that nudged Apple and John Deere into making some concessions on giving repair information to customers. A Green Century shareholder proposal in September 2021 asked John Deere to account for its anti-competitive repair policies. The following March, Deere announced that it would provide a better repair process by improving remote mobile access to equipment and the ability to download software updates on certain equipment.

Similarly, on the same day in November 2021 that Green Century proceeded with a R2R shareholder proposal, Apple introduced a new program that would provide individual consumers access to replacement parts, tools, and repair manuals needed to perform common repairs to its products. Apple said the program would launch in 2022 with the iPhone 12 and 13 lineups, followed by Mac computers with M1 chips.

Supporters of R2R know that fighting huge manufacturers is an uphill battle. Lees, the Rhode Island farmer, said he was flabbergasted to see the opposition that came out — literally, at the House Corporations Committee — to fight the bill.

Manufacturers clearly have a pile of money at stake here. In May 2021, U.S. PIRG estimated the total value of all traded shares of the major companies that contributed to lobbying efforts against R2R. That total came to $10.7 trillion. Some of the companies that put money into the fight were Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Tesla, Johnson & Johnson, AT&T, T-Mobile, Caterpillar, John Deere, General Electric, Philips, and eBay.

Proctor, of U.S. PIRG, said he is hopeful.

“We don’t live in a feudal corporate state yet; we live in a democracy. It is difficult to counteract great amounts of money in the U.S. system, but it is possible,” he said. “We are working harder, smarter, and we are right. This is an idea that wins with people.”

Consumer polls, including one by Consumer Reports, have found majorities of respondents in favor of R2R.

Existing R2R laws have passed in Massachusetts (2012) requiring “automobile manufacturers to provide non-proprietary diagnostic directly to consumers and also the safety information needed to repair their cars.” Massachusetts in 2020 required automakers to equip cars with a standardized open data platform “to retrieve mechanical data and run diagnostics through a mobile-based application.”

Colorado has passed laws affecting repairs of powered wheelchairs (2022) and farm equipment (2023).

New York’s law (2022) covers many digital electronic devices, excluding products “sold under a specific business-to-government or business-to-business contract.” Minnesota’s bill (2023) covers many digital devices, with many exemptions, but does include appliances, enterprise computing, and commercial equipment such as HVAC systems.

DIY cowboys doing the work

The fun people in this story are the get-‘er-done characters who are forging ahead on repairing electronic devices with or without cooperation from manufacturers. Among them is Brian Betances, repairman and owner of PC Tech Stores in Cranston, which he opened four years ago, after years of doing repairs informally.

Betances proudly refers to his store as a mom & pop operation and he said stores like his are becoming more numerous everywhere, with most of them specializing in a specific repair niche, be it cell phones or hoverboards.

The sphere of independent shops is evolving fast, Betances said. Ten years ago, resources for parts and technical information were scant, and people like him had to rely heavily on eBay. Now, resources to do the work include vendors of aftermarket parts, Amazon, eBay, and toolmakers. Information flows among peers, on YouTube and TikTok, and via general insider geek gossip. Getting into software to fix or to activate fixed equipment slows his work down “to a small degree, but there are workarounds.”

Asked how R2R laws could affect his business, Betances said, “Right now, we are in a boom as it is. COVID showed us that we are essential. We were doing repairs for a fraction of what it cost to replace [a device] in a financially stressful time.”

Even though Betances and his peers are not sitting on their hands waiting for R2R laws, he sees the need for R2R close up. For instance, cell phone battery replacement varies by maker. Apple glues the battery into the phone, making it difficult and dangerous to remove. Other makers screw the batteries into place, making replacement more feasible. Similar hassles apply to cell phone screens.

But Betances surely supports the principle of R2R. If we cannot repair our devices, he said, “In effect, we don’t own the things, we just rent them.”

He understands why manufacturers are fighting back. “They prefer that you replace your device [rather than fix it]. Apple is not coming out with a new iPhone every year for people not to buy it. But that sounds to me like only one side is winning.”

Betances agrees that people’s information on their devices should be secure. His answer is to develop a national brand of repair shops, which, in turn, would devise and adhere to national standards of security and integrity.

Also among the get-‘er-done crew is iFixit, with the motto “Never Take Broken for an Answer.” Elizabeth Chamberlain, director of sustainability, said iFixit, founded in 2003, is, in essence, “the missing repair manual for devices.” In its early days, iFixit would acquire castoff and non-working computers, dismantle them, and sell the parts. The company’s inventory of parts, tools, and manuals has expanded. It is a resource for deep dives into repairs, like using a microscope and micro-soldering iron to move a microchip from one device to another. (The king of this small realm is YouTuber Louis Rossman.)

In recent years, Chamberlain said, a few manufacturers, such as Google and Samsung, have taken steps to make a limited number of parts and instructions for cell phones available to the public through iFixit. The reason? With recent passage of R2R laws in four states, “manufacturers have a fire under their butts.” Even so, she said, “there is no manufacturer that has done more than a few devices with us.”

She has ready responses to claims from manufacturers, like John Deere’s claim that farmers would get into tractor software, tinker with engines, and violate emission laws. “The vast majority of farmers have no interest in souping up their tractors and violating EPA controls,” Chamberlain said. “That is illegal and would remain illegal.”

When manufacturers say compliance with R2R laws would raise their costs and force them to charge higher prices, Chamberlain retorts by observing the huge costs of the solid waste created when people must throw away repairable devices and buy new ones.

She said, across the world, only 12.5% of electronic devices are recycled, and no single country is recycling more than half its discarded devices. “We have been subsidizing repairs with the health of the planet.”

The environmental impact is both downstream — in junking electronic devices in landfills or, at best, recycling their component parts — and in the depredations on the environment to build, package, and ship the devices in the first place.

Restricting access to DIY repairs is more complicated than just foiling people who want to repair their own things,” said Proctor of U.S. PIRG. “There is a huge ecological price tag associated with” throwing unrepairable things away and buying new ones.