Historic Cemeteries Could See Grave Impacts of Climate Change in the Ocean State

October 3, 2022

Climate change is impacting almost every aspect of people’s lives … and deaths. From melting permafrost to frequent forest fires to flooding – as weather gets more extreme, so does its effects on burial grounds around the world.

In Rhode Island, historic cemeteries are particularly at risk due to a number of environmental factors, according to Charlotte Taylor, archaeologist at the Rhode Island Historic Preservation Commission.

The state has more than 2,500 recognized historic cemeteries, and many of them lie in flood zones and areas that will be affected by sea level rise.

“The most severe threat to historic cemeteries is going to be flooding, both coastal flooding, you know, giant hurricanes sweeping across the low-lying areas. But even more so… river flooding is going to be the problem,” Taylor said.

The bouts of extreme rain that will become more common in Rhode Island because of climate change will cause river levels to rise and disturb previously peaceful final resting places.

Although most of the state’s historic cemeteries are small family plots near old homesteads, during the 19th century, garden cemeteries with scenic views started to become popular. Around that time, municipalities started using land near rivers to bury their dead, not knowing that these areas would someday be vulnerable to the effects of climate change, Taylor said.

Though storm flooding could be a major threat to the integrity of historic cemeteries, general flooding and higher water tables will also have an impact on trees, which hold the ground together in many cemeteries. Falling trees, either weakened by disease, pests, or waterlogged roots, will have the potential to smash historic gravestones and reveal what’s below them.

“We have a lot of mature trees in cemeteries that are going to come down, and I bet we’re going to find burial remnants in the root balls of those trees,” Taylor said.

Flooding in other areas, including in Boston and Louisiana, have already disturbed active and historic gravesites, which then need both remediation and reburials.

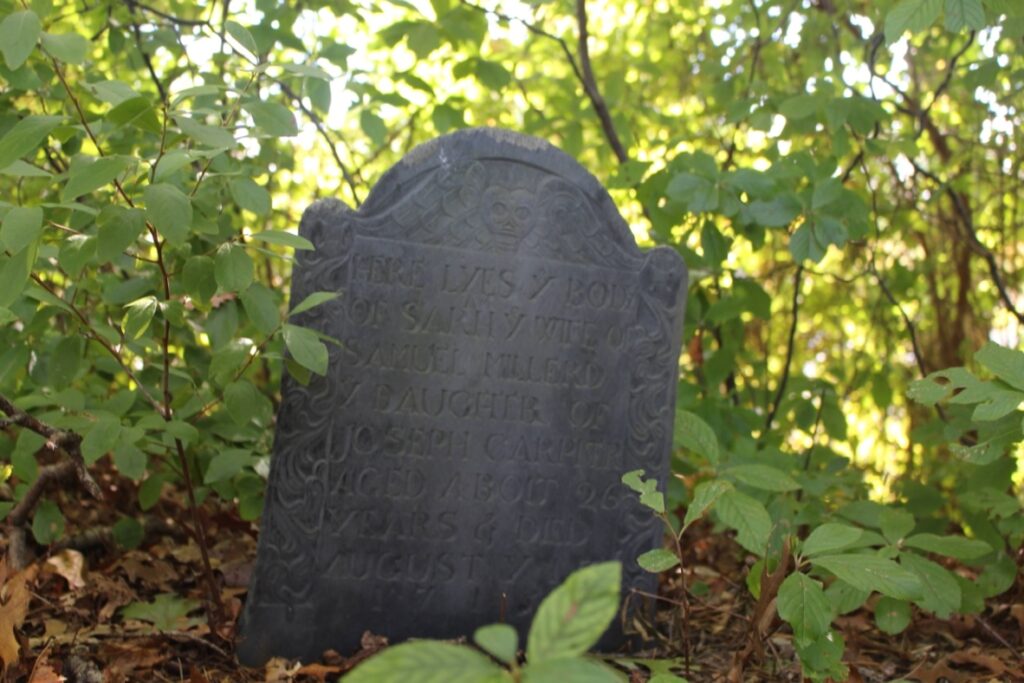

Kickemuit Cemetery in Warren, named after the river it sits on, contains some of the oldest gravestones in the state and could be vulnerable to flooding, according to Caroline Wells, an archaeologist, urban planner, and member of the Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission.

The oldest marked grave on the site belongs to John Luther, who died in 1697. A former Rhode Island governor, Josias Lyndon, who fled Aquidneck Island for Warren when the British invaded during the Revolutionary War, is also buried in Kickemuit.

Wells had her eye on Kickemuit Cemetery during her tenure as Warren’s urban planner because of its historic value, proximity to the river – between five and 10 feet from the shore in certain places – and the frequent flooding that would occur behind the cemetery on Serpentine Road.

Wells said that there is some hope for Kickemuit Cemetery.

The site sits between two dams, but the town and state are taking the structures down and restoring the waterway back to a tidal river.

“It will return it back to its more natural state of hydrology, which will return salt marshes and habitat,” Wells said. “That will be a big step. And maybe the twist here is how this might benefit some cemeteries.”

The process of returning the area to pre-dam conditions, which will lower the water levels and add back native vegetation, will likely shore up the cemetery, adding some protection from erosion, she explained.

Although Kickemuit has not yet flooded, another riverside burial ground, Precious Blood Cemetery in Woonsocket, did flood during Hurricane Diane in 1955.

The Horseshoe Dam right next to the cemetery held during the storm, but the rest of the land around it didn’t. Part of the property collapsed and washed coffins into the floodwaters.

Roger Beaudry, a volunteer at the Woonsocket Historic and Preservation Society, was 6 when Diane hit. Although Beaudry doesn’t remember any coffins floating in the river, he said he can still picture all the furniture drifting on the Blackstone River and feeling the ground rumble because of the ferocious current.

Photos in the historical society’s collection from the aftermath of the hurricane show part of Precious Bloods’ grounds fallen into Harris Pond.

In another photo, the remnants of the cemetery’s retaining wall and what appears to be a few coffins sit below the spared memorials above.

Someone once tried to donate photos of a body from Precious Blood that had washed into a cellar well, but the historic society didn’t accept them, Beaudry said.

The coffins that were recovered in 1955 were reburied in the cemetery. Now, the grounds are wrapped in another retaining wall, further back from the river.

In the years following the storm, the state and federal government spent millions repairing the damage throughout Woonsocket and installing a dam for flood protection upstream.

In the United States, most cemetery owners are not required to have climate mitigation or resilience plans, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which “leaves them vulnerable when disasters strike.”

Active cemeteries usually have a steadier income stream and larger staffs than historic cemeteries for preventing and repairing environmental impacts, according to FEMA’s “Guide to Expanding Mitigations” in cemeteries.

There aren’t many financial resources out there for the basic conservation needs of historic cemeteries, both Wells and Taylor said, so finding the money to be proactive would be even more difficult.

Documenting graves before they are damaged so that descendants can get information about their ancestors, and considering the impact other infrastructure projects will have on historic cemeteries (like in the case of the Warren dams’ removal) may be the best of limited options, Wells said.

There have been some cases of transporting whole burial grounds in Rhode Island for environmental reasons. A cemetery in Tiverton was moved to make way for the expansion of a septic field, and two burial grounds were shifted in Johnston to avoid being consumed by the growing landfill.

“Given the choice between saving a historical cemetery and saving a living community, what choice should be made?” Taylor asked. “Should cemeteries be moved back from areas where they’re going to be flooded and eroded? Is that something that tax dollars should be spent doing?”

Taylor said she didn’t have an answer but that these would be questions communities will be asking themselves as the impacts of climate change increase.

“On the other hand, if we, as a society, no longer respect our dead, what are we losing?” Taylor said. “I’m not sure what we’ll be losing, but I’m sure something.”

Colleen Cronin is a Report for America corps member who writes about environmental issues in rural Rhode Island for ecoRI News.