Proposal Would Blow Up Gales Ferry Hill to Create Quarry Along Thames River in Connecticut

January 8, 2024

LEDYARD, Conn. — Dave Harned’s wife suffers from respiratory issues, so he’s concerned a proposal to detonate a hill to create a quarry about a half-mile from their home will impact her health.

Silica dust is created by the crushing and/or cutting of materials such as stone, rock, concrete, and brick. Breathing crystalline silica dust can cause silicosis. Dust enters the lungs and causes the formation of scar tissue, reducing the lungs’ ability to take in oxygen. There is no cure for silicosis, and since it affects lung function, it makes a sufferer susceptible to infections such as tuberculosis.

“How in God’s name do you keep dust from getting airborne and escaping the property from a blast?” he asked. “You just can’t control 100 percent of it.”

A Massachusetts-based company has proposed blasting a 40-acre forested section of Mount Decatur, the site of a fort built during the War of 1812, and sell off the material, largely granite. (Mount Decatur is also known as Dragon Hill and Allyn’s Hill.) The hill is home to bald eagles, deer, foxes, turkeys, and other wildlife. All of the trees on the site will be cleared, in phases.

The well-known hill that Route 12 traverses is also home to a plaque that honors the memory of naval officer Stephen Decatur, who had an earthen encampment built when his ships were trapped by a British blockade of the Thames River. Little of the roofless fort remains, but the hill still contains artifacts from the war.

The 10,000-square-foot, diamond-shaped fort and the area around it would be preserved, according to the developers.

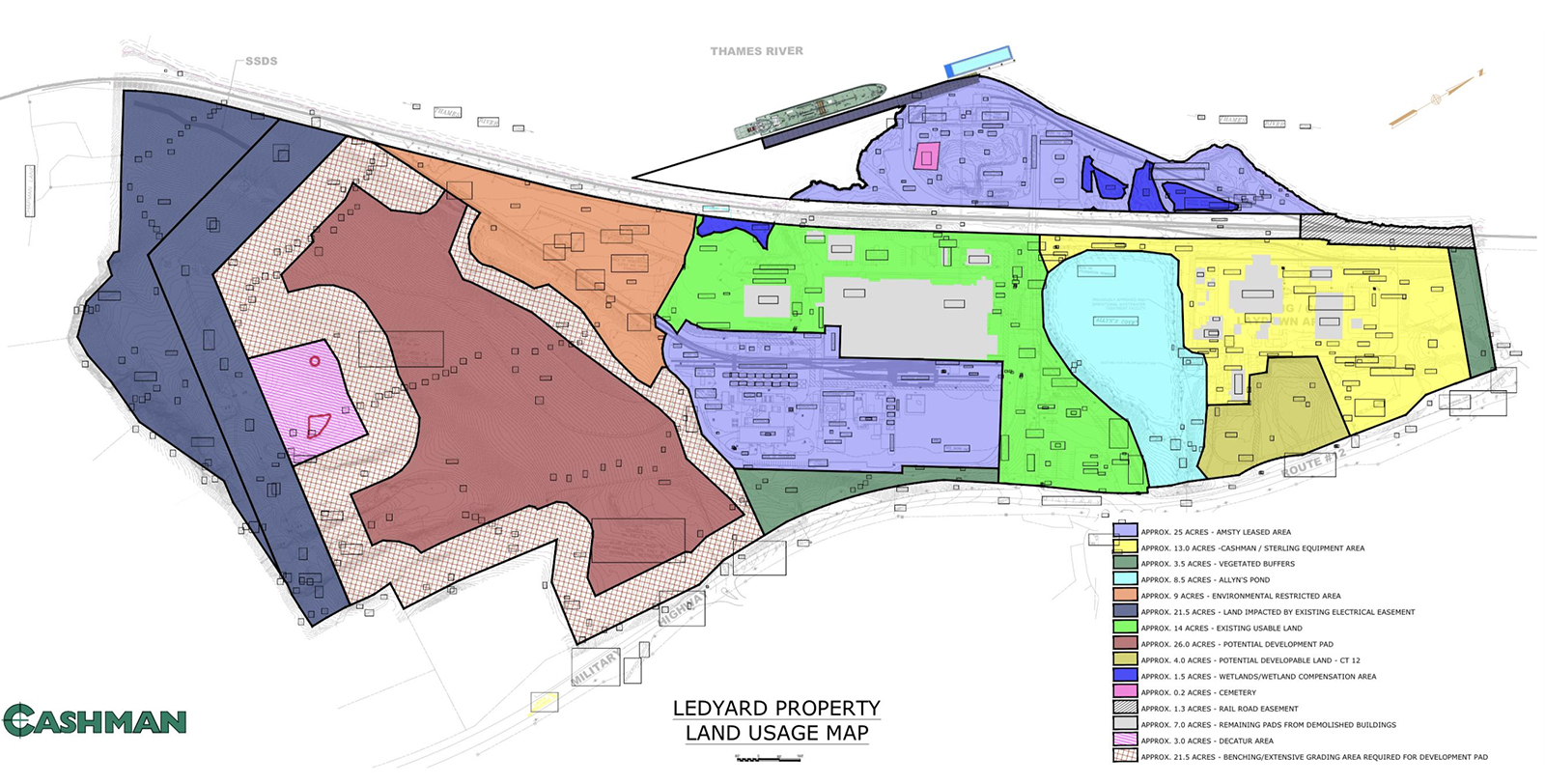

The project and property owner, the Gales Ferry Intermodal, is the latest idea Cashman Dredging & Marine Contracting Co. LLC has proposed for the 165-acre brownfield long associated with Dow Chemical. The Quincy-based business bought the waterfront property, with a dock and pier, in May 2022 for $5 million. A polystyrene plant, a Dow affiliate, leases a 25-acre lot on the property for a nominal fee.

The Gales Ferry Intermodal property is situated between marine facilities Cashman owns and operates in Quincy and Staten Island, N.Y.

Development of the quarry, which the company has referred to as “industrial regrading” or “rock regrading,” would be done in five phases over about a decade. Some environmental use restrictions are attached to the property, which has a nearly 9-acre pond.

Harned grew up in the village of Gales Ferry and moved back five years ago. His property is about 200 feet from the northern border of the Cashman property.

He recently told ecoRI News the proposed intensity in use is significantly more when compared to previous operations on the property, which is zoned commercial/industrial. He said the town’s zoning regulations state the applicant has the burden to prove, in this case, the quarry won’t have dust, noise, and vibrations that are “noxious, offensive or detrimental” to the neighborhood, and that the operation won’t cause air or water pollution.

“I personally believe that if the commissioners use our zoning language to make their decision they wouldn’t approve this,” Harned said. “I just don’t believe that they can do it without violating our zoning laws.”

Following the quarry’s operation for 7-10 years, the company’s plan is to build a complex of industrial buildings to create what it called in its application a pad of “prime, level, industrial land.”

Alan Perrault, a Cashman vice president, recently told ecoRI News that the company’s biggest interest is supporting the offshore wind industry. He said leveling the south side of the 256-foot-high hill would ultimately create 26 acres of development space to support southeastern Connecticut’s role as a hub for offshore wind energy.

The Gales Ferry Intermodal property wouldn’t be a primary assembly site for turbines like the nearby State Pier Terminal in the Port of New London, according to Perrault. He said the Route 12 site would be a support facility for extra vessels, maintenance and repair work, and businesses that accommodate the offshore wind industry. The company spent $4 million to upgrade the property’s deepwater pier to handle the needs of the industry it hopes to support.

“We understand it’s a balance between historical significance and economic development of green energy,” Perrault said.

Cashman’s application said the company would use sprayers to keep quarry dust from drifting off the Route 12 property. All the processing equipment would also have sprayers to constantly capture the dust, according to the company, and a water truck to spray the floor would always be on the site.

Perrault said every precaution will be taken to ensure blasting — to be done electronically and not with dynamite — and the processing of materials are done in a controlled way and follow industry/government guidelines to keep on-site employees and the community safe.

“Protecting workers first and foremost is the most important thing,” he said. “They’re the most impacted people. The protection provided to our employees who are right there reaches into the community.”

Blasting would be limited to between 11 a.m. and 4 pm., and other activities from 7:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m. weekdays, and 9 am.-5:30 p.m. Saturdays.

Harned and his wife aren’t the only neighbors and local residents who have expressed worry that fugitive dust, noise, vibrations, and increased truck and barge traffic would impact their health and cause quality-of-life disruptions. The community is also concerned the blasting, quarry operations, and further development on the property would impact the nearby Thames River, which supports wild oyster harvesting and aquaculture operations. The river is on the Environmental Protection Agency’s list of impaired Connecticut waters.

Concerned neighbors, including Harned, founded the Citizens Alliance for Land Use (CALU), a group of residents who organized to share their concerns with Cashman’s plans and be a conduit between the community and company.

Harned said CALU’s goal is to increase awareness “so that people know that there’s a significant issue going here and to have planning and zoning decisions be based upon facts.”

“There’s almost nothing that this project doesn’t put at risk,” he said. “Anytime you open up land, there’s the issue with where’s the water go, because you no longer have vegetation to control it and handle it.”

During a Dec. 14 Planning & Zoning Commission meeting, Cashman attorney Harry Heller said most of the material would leave the site via barge, with 100 truck trips a day expected. During the continuation of the hearing a week later, 16 residents spoke against the project.

The company has said the granite is “high quality” and will be in high demand from the construction industry. The company’s conceptual plans have shown the space being filled by a 100,000-square-foot building, a 80,000-square-foot one, and twin 40,000-square-foot buildings.

Cashman originally proposed a dredging hub for the company’s major operations in New York and Massachusetts. Facing significant public opposition, however, the company paused the application.

In 2021 the EPA fined Cashman $185,000 for dumping dredged materials nearly 3 miles outside of an authorized disposal site in Rhode Island Sound. Cashman officials said a subcontractor hired by the company made some mistakes. Cashman took responsibility and paid the fine.

The Planning & Zoning Commission is scheduled to hold another special meeting on the Cashman application Thursday, Jan. 11, at 6 p.m. at Ledyard Middle School. Cashman is seeking a special-use permit to add the excavation and processing operation.

Dow Chemical operated on the site from the 1950s to 2011. Before that, the property hosted a coal pier in the 1850s and was the terminus for a New York Ferry service, where passengers transferred to the Providence and Norwich Railroad for service to Providence and Worcester.

To view a PowerPoint presentation about the project, click here. To view site preparation plans, click here.

More criminal activity by the rich

aerial on Google Maps shows a typical subdivision driveway running west along the top of the ledge

what happened to that?

Have the proper environmental impact statements been done.

With Dow Chemicals reputation as a major polluter what lies buried on that site wouldn’t surprise me.

As the article states many species of flaura and fauna call this area home. If you decimate this mountain where will these species relocate to? My guess is that they would be on their way to extinction.