Pascoag’s Water Supply Was Spiked With Gasoline Additive; Residents Still Sick to Their Stomachs

Late last year the state of Rhode Island reached a settlement with the final gasoline refiner accused of polluting groundwater with a fuel additive

February 7, 2024

BURRILLVILLE, R.I. — The five words are still seared into my memory a dozen years later. The quote “It burns when I shower” appeared in a 2011 story I didn’t even write. The five simple words were so powerful that I stole them for the headline.

The public health crisis to which the quote refers led to some local residents taking showers at the town’s hockey rink. The problem was caused by leaking underground fuel tanks at a Mobil gas station. Residents likely drank and bathed in tainted water for months before finding out it was harmful to their health.

Two-plus decades ago, the water supply in the village of Pascoag, in Rhode Island’s northwest corner, was poisoned by the now-banned gasoline additive methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). The colorless, toxic, and flammable liquid was long used as an octane booster for unleaded gasoline. It replaced lead as an additive. One poison substituted for another.

MTBE contamination led to two lawsuits being filed. The second was settled late last year.

In early September 2001, gasoline, 7 inches deep, was discovered at the bottom of a groundwater monitoring well about 20 feet from the gas station’s underground storage tanks. Pascoag Main Street Service had five 6,000-gallon tanks, three of which stored gasoline.

The level of MTBE in Pascoag water climbed from 340 parts per billion (ppb) on Sept. 1, 2001, to 600 ppb on Sept. 17. In response, the state Department of Health recommended Pascoag Water Department customers continue to use bottled water for drinking, cooking, and food preparation and to reduce their time spent in the shower or bath, ventilate bathrooms with exhaust or window fans, give sponge baths to children who may swallow bath water, and reduce their overall water use.

Levels of MTBE measured in a bedrock aquifer near the Pascoag well reached concentrations up to 1,100 ppb — some 1,000 times higher than approved drinking water limits. Other gasoline constituents, including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes, were also detected in the well’s water and in the soil around the North Main Street gas station.

Laurel Ridge Avenue residents Norman and Margaret Desjarlais, in 2011 while a class-action lawsuit was making its way through legal channels, spoke with ecoRI News about their ordeal with the village’s MTBE-infected water. Norman said he was convinced the contamination began in May or June of 2001, not when authorities announced the problem in September.

“Even the slightest scratch would burn like hell when you were showering,” he said. “Blurred vision, difficulty breathing. We had all of that. It’s ridiculous to think that that level of contamination happened overnight.”

In the decade after the poisoned well was taken offline, the longtime Pascoag couple said they endured several medical problems, from skin rashes to skin cancer.

“Every household on our street has lost a family member to some weird, oddball cancer or had bouts with weird cancers,” Norman said. “If you look at it statistically, something is wrong here. Brain cancer, pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, the list goes on and on.”

The wife of one of their neighbors died of cancer, and the husband is currently battling a rare cancer.

ecoRI News recently spoke with the couple’s youngest son, Mat, about that time in his family’s life. He was 16 in 2001.

What Mat remembers most is how distressed his parents were.

“My parents had been through some stuff [Norman survived renal cell cancer] and they don’t shake very easily,” he said. “They were visibly scared as to what this meant. I don’t remember a whole lot about it, but I remember the feeling of seeing them that uneasy and that made me uneasy.”

He also remembers the water’s stink.

“I remember it came on all of a sudden. We were showering, washing dishes, things like that, and all we could smell was the smell of gasoline, or like a gasoline type of smell,” he said. “Your skin was so dry after showering.”

Before they where told about the MTBE contamination, Mat said his father boiled the water in hopes of eliminating the unknown problem. Boiling, however, doesn’t remove the odorous gasoline additive.

In 2015, Mat’s 2-year-old son was diagnosed with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a rare disorder that affects just five in a million people in the United States. Among the condition’s most common symptoms are skin rashes. Doctors aren’t sure what causes LCH.

“One of the leading doctors for his type of condition believes that the condition is caused by benzene exposure on the paternal side,” said Mat, who lives in Thompson, Conn. “Benzene really causes some nasty stuff.”

His son has had a few surgical procedures and endured chemotherapy for a year. The disease is in remission.

At the age of 1, the daughter of friend and fellow Pascoag native Troy Peck was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of acute myeloid leukemia. After nearly three years of treatment, including a bone marrow transplant, the disease is in remission.

“Mat and I grew up together in Pascoag, endured MTBE contamination, and we each have one child who’s endured a rare, life-threatening cancer,” Peck wrote in an email to ecoRI News.

In a subsequent phone call with Peck, he told me when his daughter was first diagnosed, the first thing he thought of was the poisoned well water that sickened Pascoag. The Cranston resident spoke of two other people he and Desjarlais grew up with who have children with rare forms of cancer.

“It can’t not be connected,” the health-care attorney said. “There’s zero way to prove that, but I can’t get that thought out of my mind.”

Peck hasn’t visited an ExxonMobil gas station for more than 20 years.

After MTBE was detected in Pascoag’s drinking water, the public well was eventually shut down, leaving many residents without a supply of water for drinking and cooking. The well served some 4,000 people, and about 40,000 gallons of water a day were pumped from its wellfield.

One local couple reportedly withdrew $5,000 from their children’s college fund to have a private well drilled. Some residents temporarily left town, and restaurant owners posted signs telling customers town water wasn’t being used.

In the initial announcement warning residents of the contamination, the Pascoag Water Department (PWD) noted that “Based on the limited sampling data currently available, most concentrations at which MTBE have been found in drinking water sources are unlikely to cause adverse health effects.”

The department’s general manager requested that, until further notice, customers either buy bottled water for drinking or get water from others not served by the utility. The notice said the “water is fine for bathing and laundry but, as always, the Utility Executive stressed the need to maintain adequate ventilation during showers and while washing and drying clothes.”

Peck said both he and his mother suffered from lightheadedness when showering before they realized they needed to open the window. He said he noticed that summer, before PWD notified its customers of the problem, that ice made with tap water “smelled like sulfur or garbage. We knew something was wrong and stopped drinking it.” They also stopped making ice with it.

The PWD told nursing homes to make arrangements with private suppliers for their potable water needs, noting a list of companies that supply potable water was available at its office.

On Sept. 7, 2001, the PWD announced two businesses had donated 1,200 cases of bottled water. “Any customer who has not received their water, please stop by the District office during normal business hours for their free case.”

A week later three other businesses donated more bottled water. Some was delivered to homes, dropped off on porches or left in front yards. The National Guard also supplied and delivered cases of water that contained six 1-gallon jugs.

A mandatory outdoor water ban took effect Sept. 18, 2001. The water ban, which PWD said would be “strictly enforced,” prohibited any outside watering of lawns and gardens, washing of cars, or any other outside use.

By the end of 2001, Pascoag’s public water system was connected to the nearby village of Harrisville’s water supply. That supply was then temporarily shut off when E. coli contamination was detected.

Twenty-two years later, the local and state responses still upset Roberta Murphy, Patty Griffin, and Mat Desjarlais. I recently spoke with the trio at Murphy’s Spring Street home.

Good friends Murphy and Griffin are older than Desjarlais and remember the ordeal more vividly. Most of their memories revolve around the doughnut/coffee shop Griffin and her parents used to own and operate on High Street. Murphy routinely caffeinated herself at Best In Donuts, even when the coffee began to smell funny and taste funky.

“I asked, ‘Are you guys, like, using something to clean the pots at night that isn’t getting filtered, because I’m getting a chemical taste in my mouth?'” Murphy said.

Griffin said the business started getting complaints about the taste of its coffee in August 2001. She also recalled being nauseous for much of that month, as she drank plenty of coffee at work.

She noted a woman who worked in the coffee shop and lived in Pascoag survived breast cancer. She recalled one of the coffee shop’s employees had a baby that summer and the mother telling her “his skin is so sensitive, he’s got a rash, especially every time I wash him up. He always seems to have a rash.”

Griffin recalled the condition of a woman who attended an October community meeting at the Knights of Columbus. “There was one woman that looked like she was wearing a turtleneck, but it was just a full-on rash,” Griffin said.

She remembered being told village residents, in October and November, were jumping in Echo Lake to bathe, afraid to shower in the contaminated water flowing from shower heads and faucets. Peck, who grew up in a house on Echo Lake, said he bathed in the lake during that time, but not when fall arrived. He noted some neighbors pumped water from the lake into their homes to shower.

Before they knew why their water tasted terrible and smelled bad, the Griffins installed a water filter. But the taste and stink remained. They eventually bought and plumbed in an 800-gallon water tank called a “buffalo.” It was used from September 2001 to well into spring of the next year, according to Griffin.

“We had to pay for the buffalo and for water to be brought in. That’s how we stayed in business,” she said. “And there was never any compensation for that.”

The Griffins closed their longtime business in 2005 — not because of water woes, but the opening of a Dunkin’ Donuts down the street.

In 2012, the class-action lawsuit resulted in a settlement with ExxonMobil for $7 million. The Griffins received $300 and, according to Desjarlais, his parents got “two hundred and something dollars.”

Remediation of the Mobil gas station property was exhaustive. Some 12.5 million gallons of groundwater were pumped from the area, treated through carbon filters, and discharged into the Pascoag River or into the town of Burrillville’s wastewater collection system. It has been estimated that some 3,100 equivalent gallons of gasoline were removed from the property.

The state Department of Environmental Management reported local residents complained of massive headaches, vomiting, wheezing, and blisters on their lips.

Longtime Pascoag resident Janice Kaplan told ecoRI News in 2011 that she suffered from chronic ear, throat, and lung infections, chemical burns, and elevated liver function. After showers left her husband’s skin burning, he began showering at the June Rockwell Levy Community Ice Center, she said.

Kaplan said her family seemed to be caught in a revolving door of infections and rashes. Her oldest daughter, she said, also suffered from extremely elevated — to the tune of four times higher than normal — liver function.

“Everybody around you was sick or hospitalized,” she told ecoRI News.

The village of Pascoag, one of nine that makes up the town of Burrillville, wasn’t the only area of Rhode Island contaminated by MTBE leaking from underground fuel tanks, however.

Fifteen years after the Pascoag contamination was identified and four years after ExxonMobil was fined, officials took action statewide against those responsible for MTBE contamination. The seven-year court battle recently ended.

The Rhode Island attorney general’s office, in December, resolved a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, the final gasoline refiner named in the state’s 2016 lawsuit, for its role in polluting Rhode Island’s soil and groundwater with the fuel additive.

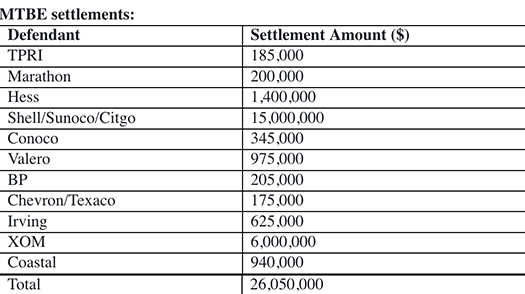

Rhode Island had previously entered into settlement agreements with other major refiners for their role in MTBE contamination.

“We have now settled with every major gas refiner named in our lawsuit and returned more than $26 million in damages to the people of Rhode Island,” Attorney General Peter Neronha said when the $6 million ExxonMobil (XOM) settlement was announced. “These oil and gas companies knew about the dangers of MTBE well before the public did, and for that, we made them pay.”

Did we make them pay, really? Do we ever make the fossil fuel industry pay for the pollution and the associated health impacts it causes? The settlements the industry agrees to pay only amount to a fraction of its annual profits. As the cases are dragged out in court, taxpayers often foot the legal bills while the industry is rewarded with billions in federal subsidies annually.

Peck called the settlements “a joke.”

“They paid their attorneys more than that to defend them,” he said. “No plaintiffs were made whole. They just think a few people were inconvenienced by some bad-smelling water.”

He’s right. The money eventually gleaned from Big Oil never comes close to paying for the damage its products create. No corporate CEO ever goes to prison. They are never even charged, despite knowing, and often hiding, the dangers.

Besides Pascoag residents getting sick and, at least initially, not knowing why, being without potable water caused families mental and emotional stress. They had to depend on bottled water to drink, cook, and brush their teeth. They had to jump in a lake or visit an ice-skating rink to shower. Trust lost. Life dangerously interrupted. Human health diminished. People scared.

Neronha said the $6 million from the latest ExxonMobil settlement would be used to remediate contaminated waters. The cost of cleaning up an MTBE plume is significant, and taxpayers are routinely left holding the bill or paying for state and/or federal officials to take the responsible parties to court.

Research has shown that MTBE’s presence in drinking water, even at low concentrations, can pose serious health risks. MTBE can give water a strong turpentine-like taste and odor, its removal is costly, and it’s considered a probable human carcinogen.

MTBE was added to gasoline in the mid-1980s to increase fuel efficiency, with peak usage during the 1990s. The fossil fuel industry said the petroleum byproduct would reduce ozone and carbon monoxide levels.

When MTBE started to be detected in groundwater, several states banned its use in gasoline. It hasn’t been added to gasoline in the United States since 2005, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rhode Island’s 2016 lawsuit alleged that fossil fuel corporations promoted, marketed, distributed, supplied, and sold gasoline and other petroleum products containing MTBE, when they knew, or reasonably should have known, that MTBE would be released into the environment and cause contamination to the state’s water supplies and threaten public health.

The state’s previous settlements with Big Oil have funded several remediation projects. For instance, DEM has performed remediation at the Community Baptist Church in Pascoag, using a compound to supply oxygen for enhanced aerobic biodegradation, feeding bacteria that eat the contamination.

The church bought the property at 175 Church St. after the gas station was demolished in the 1980s. In 2020, 254 tons of contaminated soil were excavated from the site.

Work has begun at Edwards Garage in Hopkinton, and future remediation efforts have been identified in Cranston, Foster, and Tiverton.

In announcing the December settlement with ExxonMobil, DEM director Terry Gray noted MTBE has had “direct impacts on the environment in Rhode Island.”

Petroleum refiners termed MTBE an “anti-knocking agent.” The petrochemical is made by blending isobutylene and methanol — isobutylene is derived as a byproduct of the petroleum refinery process and methanol typically is derived from methane. The fossil fuel industry claimed the toxic byproduct was going to lessen air pollution by making gasoline burn cleaner.

Everything the industry touches gets sick.

By the mid-1990s, it was being reported that MTBE was eating away rubber fuel lines, leading to car fires and recalls. As of December 2020, the United States was still exporting the poisonous concoction, according to the CDC.

(Fuel ethanol has since replaced MTBE as a gasoline additive. Corn-based ethanol, which for years has been mixed in huge quantities into gasoline sold at U.S. pumps, is likely a much bigger contributor to global warming than straight gasoline, according to a 2022 study.)

MTBE has been shown to cause cancer in rodents, most notably in their kidneys and livers. Humans exposed to MTBE experience an increased frequency of respiratory, allergic, and neurologic reactions. Symptoms include a cacophony of unpleasantness: headaches; nausea; vomiting; burning sensation in the nose, mouth, or throat; cough; dizziness; nosebleeds; eye irritation; spaciness and disorientation; breathing problems; fatigue; inability to concentrate; shortness of breath; anxiety; depression; stomach cramps; poor memory; insomnia; and loss of appetite.

In Rhode Island, and across the country, underground tanks filled with unleaded gasoline spiked with MTBE inevitably began to leak. Leaking MTBE doesn’t act like other components of gasoline, which stick to soil and biodegrade. It stayed intact and traveled with the flow of water. Groundwater was contaminated and drinking water supplies abandoned, often after the tainted water had made people sick.

“We’ll probably be living with this for a long time,” Murphy said.

Note: To read the ecoRI News stories from 2011, click here, here, and here.

Frank Carini can be reached at [email protected]. His opinions don’t reflect those of ecoRI News. The organization’s co-founder was the editor from 2009 to 2021.

I remember my mom who had a horrible rash on her face and passed away from cancer in 2002 was drinking this water for many years . I drank it too when I visited her along with my children not knowing that the water was poisoned.

How many more of these underground tanks are leaking? The entire country is full of them. Was exxon mobile or the company who made the tanks ever made to evaluate them after this law suit? They could use underwater snake line cameras like the sewer folks use. And relign them like the septic religning, or fill them with concrete after removing the gas.

“Our society is run by insane people for insane objectives. I think we’re being run by maniacs for maniacal ends and I think I’m liable to be put away as insane for expressing that. That’s what’s insane about it.” – John Lennon

The hair fell off of my dog. I have chronic health issues. IDK if it’s from the water. 💦 but I remember it was a really bad time living here. Before companies donated water, you had to take cleaned out milk jugs to the Harrisville Fire Dept, stand in line and fill up your jug. My kids were in college at the time so they were not affected. And putting water in milk jugs was pretty sketchy too. You had to put a couple of drops of bleach in the jug, so the water wasn’t contaminated from any residual milk. That was such a bad time and it was hard to get the cases of water into my house. I had stairs leading up to my property then stairs to the porch area. One time they delivered the water early and it was winter and I had to go to work and didn’t have time to take it in the house, so I figured I would bring in when I got home from work. I got home at midnight and someone stole all my water. I felt so defeated.

This article is infuriating. I lived in nearby Harrisville at the time, from 1999-2002, literally a stones throw from the Pascoag water wells , but fortunately had Harrisville water supply at that time. The first hand accounts of friends and familiar acquaintances becoming ill because of this blatant negligence on the behalf of Big-Oil and watching them, basically get away with murder, by blaming the pollution on the “operator” of the station is so profound. The fact that the State AG has only been able to achieve $26 million in damages as a result of the lawsuit prevalence on this case is absurd.

This is akin to the manufacturers of PFAS, in that they’ll never truly be held accountable as responsible parties, is maddening!

Exxon-Mobil should have to drink the poison they made Pascoag’s population drink. This is so infuriating to the point that 24 years later this wound still feels fresh.

The society we live in, the rules we play by, the maniacal society by which we live in and the unfairness corporate power has over government offers no hope our children will ever have a healthy and prosperous future.

We’re all victims, yet we all contribute to the same problem. Is there really any answer? Mobil should’ve been found more at fault and the State should’ve grown a set of kahunas and challenged the ruling further for a larger settlement. $26 million is a joke, a piece of northern RI is forever in ruin.

How will we ever get away from poisons that continue to kill us?