Offshore Wind Industry Plans Comeback in 2024 After Battering by Economic Tsunami Since 2020

December 14, 2023

The Pulitzer Center supported this story through its Connected Coastlines project.

The promise of scores of wind turbines fixed to the ocean floor offers hope for renewable electricity for the 40% of Americans living closest to the country’s windy coasts. Global events gave the offshore wind industry a hard smackdown starting in 2020, leading to postponements and cancellations of projects, including some in and near Rhode Island.

People in the industry — backed by billions of federal dollars and sustained support by states — have declared the industry can right itself. In fact, they say, it must. The nation’s economy and skilled workers need the enormous investment that supports the installation of offshore wind projects; above all, global warming must be reined in with more renewable energy sources.

These goals have strong support from the Biden administration and many states, including Rhode Island, as expressed in its 2021 Act on Climate and 2022 Renewable Energy Standard.

In addition to the five-turbine Block Island Wind Farm, the first commercial project in the United States, two other new northeastern offshore wind projects have steel in the water: South Fork, based on Long Island, N.Y., producing electricity for New York; and Vineyard Wind, based in New Bedford, Mass., under construction and expected to begin pumping electricity soon.

These projects are costly. The recently approved Revolution Wind project, which is expected to start sending electricity to Rhode Island and Connecticut in 2025, cost $1.5 billion.

Planning for these projects begins at least a decade before they enter the water. A risky factor is that the price utilities will pay for electricity is locked in via power-purchase agreements that are inked years before operations begin. That price can’t change for the 20-year life span of the turbines.

The gut punches that the industry has suffered since 2020 came from three or four unpredictable and almost-surreal causes. Ultimately, the problem comes down to money: the cost of construction got too high for the projects in the pipeline to sustain.

The tough 2020s

First came the pandemic. Global manufacturing and trade and transportation slowed to a crawl. Dollars chasing scarce goods led to fears of inflation and spikes in interest rates.

The U.S. inflation rate was 1.9% in 2018, around the time that power-purchase agreements for several offshore wind projects were being calculated. The rate jumped to 6.8% in 2021 and to 7.1% in 2022. The core inflation rate was 3.1 percent on Dec. 12.

Interest rates followed a similar path. In 2017, the federal interest rate was 1.33%. As of November 2023, the rate was 5.33%. The biggest jumps in the interest rate were 6,086% from 2021 to 2022 and by 24% from 2022 to 2023.

Dugan Becker, spokesperson for the SouthCoast Wind project, explained how developers predict pricing for a commodity two decades into the future.

“Price is calculated through a really complicated math problem that takes into account the entire economic climate of the time, like what are steel prices, what do turbines cost, how much do we expect to spend on work force, and what are the reasonably foreseeable economic risks that we might encounter,” he said. “The period 2018-2021 was when many power-purchase agreements were awarded and revenues were locked in. The actual costs that these projects are incurring are now much higher. Essentially, they sold low and bought high.”

Kris Ohleth, executive director at Special Initiative on Offshore Wind, said, “In a new paradigm in the future, when we know how much offshore wind will cost, the developers will bid appropriately.”

Developers and utilities are indexing the price of electricity to inflation in power-purchase agreements under negotiation now to make these investments more feasible for developers. Experts say indexing is crucial for the industry. Energy officials in Rhode Island are considering 30-year contracts rather than the more-common 20 years, because the cost to ratepayers can be borne across another whole decade.

War zone competition

The next whack was the war in Ukraine, which led countries of western Europe to expand their existing offshore wind capacity to reduce their reliance on Russian oil. European countries, such as as Denmark, the United Kingdom, and others began building offshore wind farms more than 30 years ago. Currently, 10,000 offshore wind turbines are spinning in Europe and Asia. (China has the most offshore wind turbines of any country.)

The enormous supply chain needed to create these facilities — for turbines, blades, electronics, foundations, cable, specialized machinery, substations at sea and on land, specialized boats, beefed-up port facilities — is in Europe and China. Not a single turbine is made in the United States. Global competition for these resources is keen.

“Projects in the U.S. are retrenching while Europe and China are doubling down,” Ohleth said. “The supply chain needs a pipeline [to projects]. The challenge with the supply chain is, will it follow where the projects are?”

Another body blow since 2020 or so is the higher cost of materials because of inflation and scarcity. The Offshore Wind Market Report 2023 by American Clean Power declared, “By weight, offshore wind uses more steel than any other material. While steel prices have started to come down from pandemic peaks, prices in North America and North Europe remained 52% and 69% above January 2019 prices at the end of 2022.”

The CEO of Danish energy company Ørsted, developer of the Block Island and Revolution Wind facilities, said last August the company could be prepared to write off up to $5.6 billion at proposed projects on the East Coast because of supply chain and other problems. CEO Mads Nipper was quoted as saying, “We are willing to walk away from projects if we do not see value creation that meets our criteria.” Ørsted’s shares dropped 25% after his comments were reported.

Money — the high cost of borrowing; the locked-in pricing; the uncertainty of funding, at least before passage of the 2021 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022 — is the essential problem. Coming up behind the financing problem is the very slow permitting process in the United States, requiring many federal and state layers of studies and sign-offs, including many to protect the environment. Such long time frames allow catastrophic events to sidetrack the process.

Some experts have said the process of permitting and building an offshore wind project has parallels to building a nuclear power plant because of the long time frame, initial high costs, environmental questions, lots of permitting, and potential for disruptions along the way.

Brace for arithmetic

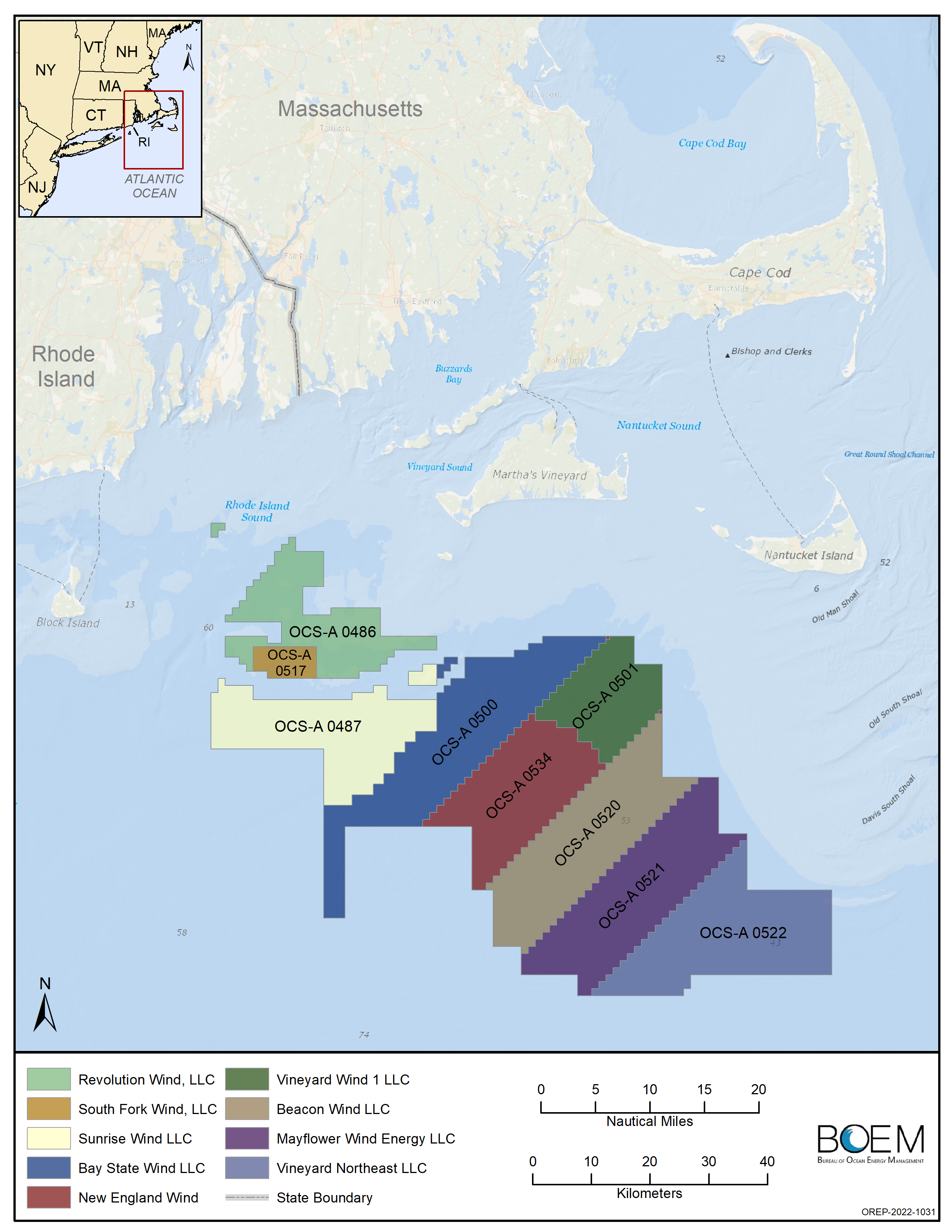

Three offshore wind facilities — two of them very new — are now functioning in New England. All of the wind farms would sit in a patch of federally controlled waters above the Outer Continental Shelf that is east of Montauk, N.Y.; southeast of Block Island; and south or southwest of Martha’s Vineyard. This “wind energy area” is sliced into expanses the federal government leases to developers.

[Little bit of arithmetic here: there are 1,000 kilowatts in one megawatt. Wind farm generation is usually expressed as megawatts (MW). Use of electricity is often expressed as megawatt-hours (MWh) or kilowatt-hours (KWh). Rhode Island Energy says a typical residential customer uses 500 KWh a month.]

The five Block Island Wind Farm turbines, spinning since 2016, produce 30 MW of power for Block Island. The starting price was 24 cents per KWh.

South Fork Wind, now operating, has 12 turbines producing 132 MW, cabled to Long Island. The price of electricity is $160 a MWh, or 16 cents a KWh.

The 62 turbines of Vineyard Wind will produce 400 MW for Massachusetts, and is priced at $74 a MWh, or 7 cents a KWh.

Revolution Wind is under construction. Its 65 turbines will send 400 MW of power to Rhode Island and 300 MW to Connecticut. The price of electricity is $98.43 a MWh, or almost 10 cents a KWh.

Headwinds of 2023

Other projects have stalled.

SouthCoast Wind (originally called Mayflower Wind) had two contracts with Massachusetts utilities that, combined, would have sent 1,200 MW of power into Brayton Point in Somerset, Mass. The original price would have been $70 a MWh. In June SouthCoast paid a penalty of $60 million to terminate the contracts. Rebeca Ullman, spokesperson for SouthCoast Wind, said “Covid-related supply chain disruptions, rising interest rates and the war in Ukraine made the contracts unfinanceable.”

Ullman noted that a February offshore wind industry analysis concluded that the costs of building and operating offshore wind farms have increased well above 20% since 2019. Ullman said SouthCoast would participate in a new request for proposals (RFP) that is being offered jointly by Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, with bids due the end of January.

Sunrise Wind, with 84 turbines, had proposed to produce 924 MW for sale to New York utilities, with cables making land on Long Island. The project stalled in the fall after New York regulators turned down requests by the developers to charge customers higher fees under future power-sale contracts. On Dec. 11, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management accepted and published the final environmental impact statement for Sunrise.

Commonwealth Wind, with contracts with Massachusetts utilities, struck a deal this year to back out of the 1,200-MW project, paying termination fees of $48 million.

Revolution 2 would have created 884 MW of power. Rhode Island Energy turned down the proposal in July, saying the proposed price for electricity was too expensive.

Farther south, Ocean Wind 1 and 2, based in New Jersey, were canceled in October because of project delays due to supply chain disruptions and rising interest rates.

(Prices noted above are as of the end of 2021 and are from OffshoreWindPower.org. The link also shows the levelized cost of electricity, defined as the present value of the total cost of building and operating a power plant over an assumed lifetime. Levelized prices often are lower than year-one prices.)

Future strategies

Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts all have RFPs for projects in place at this time; deadlines for the RFPs are late January into February. Together, the three RFPs are soliciting 6,000 MW for electricity generating capacity. Significantly, the three states signed a memorandum in October that allows developers to bid on one or two or three of the RFPs, with preference given to multi-state proposals. The objective is to lower costs via greater efficiencies and economies of scale.

Jeff Tingley, managing partner of OSWind Partners and an adviser to Rhode Island Commerce on offshore wind, helped write Rhode Island’s Strategic Plan for Offshore Wind Jobs & Investment. He said economies of scale via more projects in a single area are “very powerful” in lowering costs. “It makes a substantial difference.”

One of the big problems, and enormous opportunities, of offshore wind is to create a U.S.-based supply chain to allow the country to step away from the competition for Europe- and China-sourced supplies, and also to boost the U.S. economy and create — or move workers from the old energy economy into — skilled jobs.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) says if the country is to deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030 — a goal enunciated by the Biden administration — the industry will need 2,100 wind turbines and foundations, 6,800 miles of cable, and almost 100 vessels for installation, crew transfer, laying of cables, transport, and servicing. All of this, along with new and expanded ports to accommodate much heavier loads than many ports have ever seen.

Further, the NREL says employment in a fully built-out domestic industry could create 10,000 full-time jobs and up to five times as many jobs for suppliers across the country. The laboratory put the price tag of $22 billion on its vision.

Projects to help create a domestic supply chain overlap, in some cases, onto the topic of local economic development. RFPs for offshore wind developments, Tingley said, typically include requirements for the developer to support other enhancements to the local economy. That could include manufacturing facilities, major port improvements, environmental research, and workforce training.

A typical RFP for a wind farm, Tingley said, might tell bidders: “if our state chooses you to do this wind farm project, you also must build … say … a turbine manufacturer.” Part of the agreement would be the amount of money that the state would be willing to kick in to the required capital project.

Millions of federal, state, and private dollars have flowed into Rhode Island and other OSW-welcoming states to support the industry. Chris Waterson, CEO of Waterson Terminal Services, which manages the Port of Providence, names, for starters, the 2016 state bond of $2 million, approved by voters, to expand the port, including onto land that would later accommodate Ørsted facilities.

Last May, Ørsted and co-developer Eversource promised $100 million to the port to expand its capacity as an offshore wind hub. Ørsted has partnered with two Ocean State shipyards to build five crew-transfer vessels. In 2022, Orsted awarded a contract for infrastructure needed for OSW crew helicopters based at Quonset State Airport, injecting $1.8 million into that facility. Ørsted gave $4 million to Quonset Business Park and its Port of Davisville for facilities to service OSW vessels.

Early this year, Ørsted pledged $35 million to Quonset Business Park for a Multimodal Offshore Wind Transport & Training Center, but that was part of Ørsted’s stalled Revolution 2 wind farm proposal, so that spending is on the shelf at this time, said David Preston of New Harbor Group, spokesperson for Quonset. Also, Ørsted has promised $1 million to an offshore worker training project jointly with Rhode Island.

In Connecticut, Ørsted committed more than $100 million in direct investment in redeveloping the State Pier at the Port of New London, where turbines will be staged and assembled.

Another state/private initiative is the recently announced investment of $35 million from the state and an equal amount for Waterson Terminal Services to develop the South Quay in East Providence into a staging and shipping area for offshore wind turbines.

Rhode Island and its neighbors are not unique in investments by and for offshore wind. A U.S. Department of Energy website has an exhaustive breakdown of places across the country where manufacturing, port improvements, substation assembly, and boat-building for offshore wind is happening.

A map by American Clean Power shows color-coded dots across the country highlighting enterprises involved in manufacturing, boat building, research, workforce development, and ports. Among them is the construction, in Texas, of the first U.S.-made wind turbine installation vessel, an important benchmark.

Tingley said these economic development investments that states may require of developers can “jump-start investments.” Rhode Island has not imposed specific economic development demands — like “build us a steel mill” — on wind developers, Tingley said. But the state directs developers to look closely at topics such as upgrades to ports; development of an operations and maintenance hub here; and promotion of environmental justice initiatives for people historically suffering from environmental depredations.

Show me the money

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which supports renewable energy in many forms, is an enormous and crucial support for offshore wind. It provides a 30% tax credit for projects. Another 10% credit is available for projects that use 100% domestically made iron and steel.

Yet another 10% is available for projects in “energy communities.” This generally means communities and workers that once depended on old and displaced industries based on fossil fuels. Think of the shuttered, coal-burning Brayton Point power plant or the coal mines of West Virginia.

In September, governors of six coastal states, including Rhode Island, wrote to the Biden administration with three specific appeals intended to help offshore wind development. The letter opened with a description of financial stresses on the projects and said, “Absent intervention, these near-term projects are increasingly at risk of failing.”

First, the letter pleaded for greater clarity on whether all tax credits under the IRA fully apply to offshore wind. Next, the governors asked that some of the revenue that now goes straight to the U.S. Treasury from the lease of tracts of seafloor for wind farms be shared with the states where people buy the electricity. Finally, the governors asked for a reform of the permitting process to make it work faster, stating, “slow permitting timelines have the potential to severely limit our ability to grow the clean energy economy.”

Offshore wind projects deal with opposition from citizens and whole industries — for example, commercial and recreation fishermen — who vent their feelings and muscle via numerous public hearings, organizing, and lawsuits. Revolution Wind, now under construction, is challenged at present by lawsuits in state and federal courts from Green Oceans, an East Bay-centered citizens group, and from the Preservation Society of Newport County. Objections range from fears of the impact on the ocean environment, to hobbling of the fishing industry, to worries about unsightliness of turbines from shoreline properties.

Ohleth, of Special Initiative on Offshore Wind and a resident of New Jersey, where opposition to offshore wind has been fierce, said developers consider public opposition one of many risk factors that need to be dealt with. On the risk register, however, she said public opposition “is not the factor they [projects] will live and die by. Macroeconomics is a bigger factor.”

People who support more offshore wind development acknowledge the current problems but seem to see a future of adaptation and growth as nearly inevitable. The Biden administration and its Inflation Reduction Act are strong supporters. States want and support offshore wind to reach their renewable energy goals. Labor unions are in favor of new, skilled jobs. The potential expansion of skilled manufacturing and creation of a giant domestic supply chain is eye-popping. Europe and China offer three decades of experience and know-how. Environmentalists are revved up. The problems of the 2020s are lined up for creative solutions.

“The three projects that are under construction need to get built,” Tingley said. “When they are up and operating we will see a resurgence in excitement, and it will validate that we can build these things.”

Other observers often say, simply: we are seeing the birth of a new industry.

The Pulitzer Center supported this story through its Connected Coastlines project.

Hello

If the turbine lifespan is only 20 years, who will be responsible to remove and recycle all these materials?

Barbara Milotte

https://blog.ucsusa.org/charlie-hoffs/what-happens-to-wind-turbine-blades-at-the-end-of-their-life-cycle/ Wind Turbines can be recycled. They are working on ways to recycle blades that are mostly ending up in landfills. They will not contaminate the soil as waste from forms of non-renewable energy — such as wastewater from fracking which contaminates our soil and groundwater. The burning of “natural” gas from fracking and other sources, not to mention the burning of coal creates air pollution, GHG emissions, etc. The problem recycling of wind turbine blades can be solved unlike the irreparable damage to planetary and human health caused by oil and gas extraction, production and use.

Climate justice is the basic building block of future Rhode Island prosperity for the foreseeable future. Any economic plan that does not have that principle at its heart is just plain not going to work for our communities, even if the rich love it.

These boondoggles are infeasible if not “backed by billions of federal dollars and sustained support by states” and of course the price will ultimately fall on ratepayers and ocean life. And by the developers own admission they will not accomplish what are purported to do. They will only “displace” emissions, rather than reduce or eliminate them.

FACT: Industrial wind turbines do NOT have a lifespan of 20 years…as has been documented with land-based wind power failures. The premise of 20 years is one of many wind industry myths (lies if you will).

Might you explain more clearly what “climate justice” entails?