Expensive Wastewater Upgrades Pay Off for Narragansett Bay

August 11, 2022

The investment Rhode Island has made in upgrading its wastewater treatment facilities has paid dividends for the Ocean State’s signature attraction.

A research paper published last month in Frontiers in Marine Science on the health and eutrophication of Narragansett Bay found nutrient loads between 2013 and 2019 were reduced and seasonal low-oxygen (hypoxia) events lessened.

The paper “synthesized” various aspects of long-running research projects in parallel with treatment-plant upgrades and how Narragansett Bay, especially the upper bay, responded, according to Dan Codiga, the paper’s lead author.

He co-authored the paper with Heather Stoffel, a marine research associate with the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography (GSO), Candace Oviatt, a professor of oceanography at GSO, and Courtney Schmidt, staff scientist for the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program.

Their work examined Narragansett Bay, a warming urban estuary with seasonal hypoxia, during June through September from 2005 to 2019. During those 14 years, Rhode Island wastewater treatment facilities were upgraded to remove nitrogen. The mean 2013-19 bay-wide total nitrogen load was 34% less than the 2005-12 mean, according to their research.

A high-profile fish kill in Greenwich Bay in 2003 galvanized public support for action on nutrient reduction, although, as the paper noted, the cause, in this case, was wind-driven stagnation of circulation as much as excess nutrients.

The General Assembly soon passed legislation to reduce nitrogen loads into the bay from wastewater treatment facilities, as a means to help decrease phytoplankton levels and alleviate hypoxia.

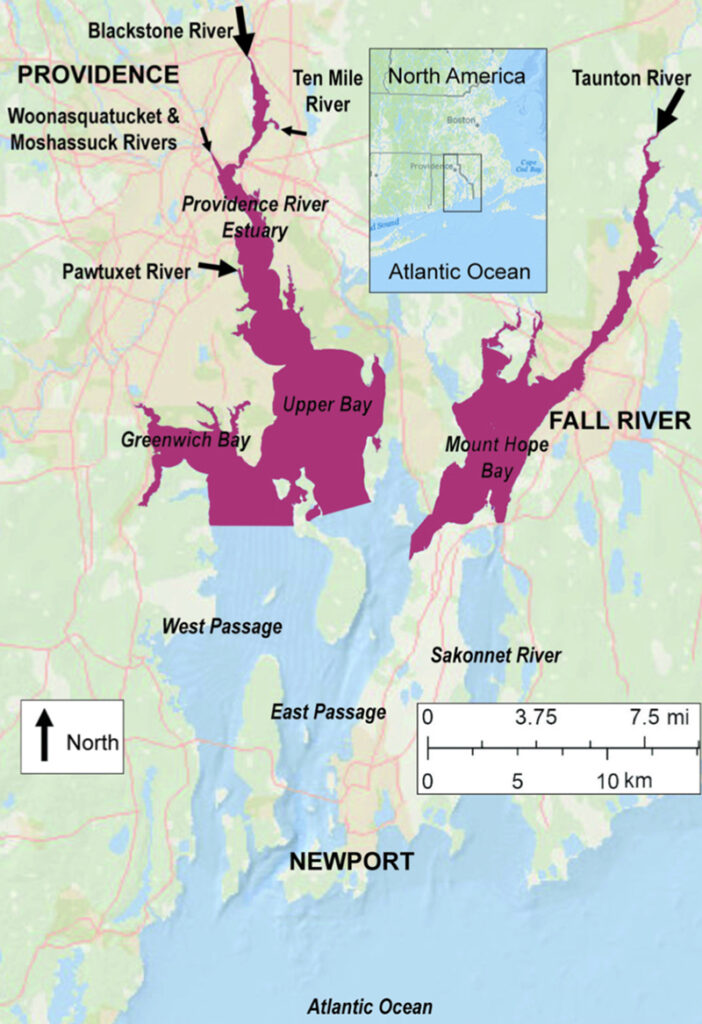

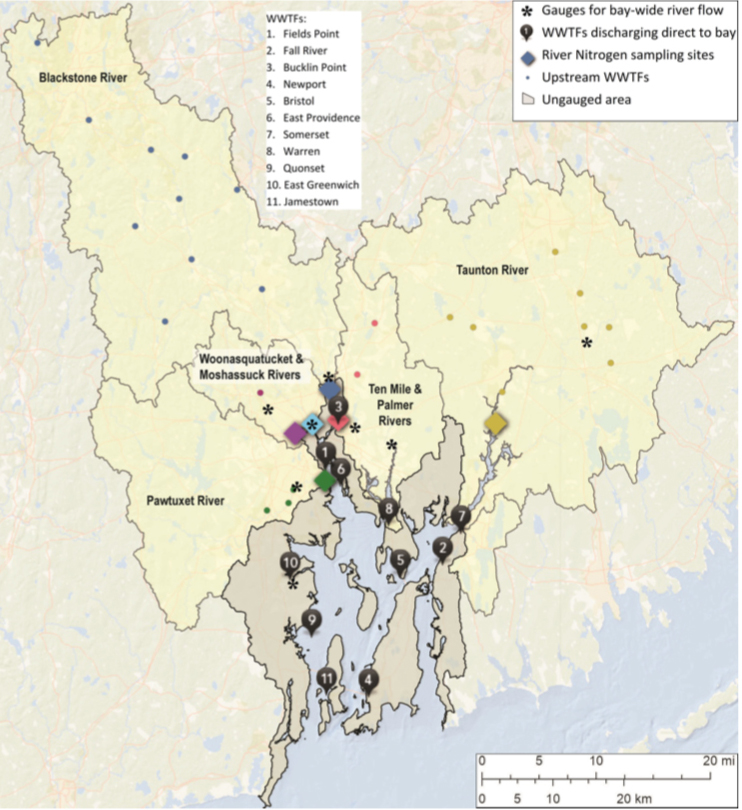

For urban estuaries such as Narragansett Bay hosting large human population centers, Providence and Fall River, Mass., wastewater treatment plant discharges are often a major source of nutrients.

From 2005 to 2013, much of the required and expensive upgrades to 11 of the state’s 19 major wastewater treatment facilities, which have 240 pumping stations and hundreds of miles of sewer lines, were conducted. Improvements are still being made, but the taxpayer-funded effort has worked as intended.

The 16-page report found that in Narragansett Bay, despite its numerous river inputs and broad geographic distribution of treatment facilities, periods of high-chlorophyll and low-oxygen events have declined.

“Our findings support the hypothesis that load reductions are responsible for the phytoplankton decline,” the report states.

Codiga and his fellow researchers examined a variety of datasets to determine the impact wastewater treatment facility upgrades are having on Narragansett Bay water quality. They found load reductions of nutrients explained chlorophyll and hypoxia declines better than physical processes such as river flow, stratification, tidal variations, winds, and temperature.

“Managed Nitrogen Load Decrease Reduces Chlorophyll and Hypoxia in Warming Temperate Urban Estuary” built on research done by others dating back decades and on projects Codiga and his colleagues have been working on since 2005, back when he was working full-time at GSO.

“We looked a lot of different factors, including the potential role of winds,” Codiga said. “In some estuaries the winds are a crucial control over when and where hypoxia occurs and how severe it is. In our study we looked at all these things together. That’s why I think of it as a high-level synthesis. … You have to study this for a long period of time because the inter-annual changes from year to year are large.”

Their research also showed that without warming, the managed load decrease would have curtailed hypoxia more effectively. But long-term warming being caused by climate change will continue to influence the bay’s water quality.

“Climate trends should be at least as important to future eutrophication as the managed load decline because, in addition to warming influences, long-term increases in river flow would increase load and stratification,” according to the paper.

Eutrophication due to excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, from human activities threatens water quality in estuarine and coastal waterbodies worldwide. Too much phytoplankton provides large amounts of organic matter that fuels bacterial consumption and the depletion of oxygen. Two key symptoms are high levels of chlorophyll, an indicator for phytoplankton, and hypoxia, which degrades habitat for many marine species, including fish and shellfish.

Hypoxia in Narraganset Bay occurs as a series of events, each lasting from days to weeks typically in July and August.

For Narragansett Bay, phosphorus plays far less of a role in nutrient loading, the paper noted. Phosphorus in the bay declined by 56% in the 1990s because of its removal from detergents and implementation of controls in its watershed.

While nutrient loading, most notably nitrogen, plays a big role in low-oxygen events, a diverse range of factors actually dictate water quality, according to Codiga. He said influences can include residence times as set mainly by circulation processes, freshwater/river inputs, and sediment fluxes. Both stratification — the separation of water in layers — and oxygen can also be controlled by a range of physical processes, including wind-driven currents and changes in mixing associated with tidal currents.

“The bay’s conditions vary a lot from year to year simply due to whether there is heavy river runoff or heavy precipitation during the summer,” Codiga said. “If we have a really wet summer, we have a lot of extra nutrient load. Conversely, when we have a dry summer, water quality conditions tend to be better — less load and less phytoplankton and hypoxia is less likely to happen.”

He noted this summer has so far been very dry, while last summer was very wet. Wet summers, when the bay’s water temperature is high, mean stormwater runoff carrying nutrients such as nitrogen from lawn fertilizers feeds phytoplankton and the low-oxygen conditions that result.

Codiga said he and his colleagues’ ongoing research will eventually examine the impact the summer of 2022 and 2021 had on Narragansett Bay’s water quality.

In 2014 Codiga took a full-time position at the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, but the Boston resident continues his research on Narragansett Bay, by “moonlighting” and through small contracts with organizations such as the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program.

His training and background are mainly in physical oceanography and eutrophication and processes in coastal waters and estuaries.

“costly” was in the title but not explored in the article. Narragansett Bay Commission rates have skyrocketed, paid by those in their area based on how much water they use. But the problem is largely runoff from heavy rainfall that overwhelms the system. It would be much fairer to charge by the amount of runoff, for example a huge CVS parking lot in North Providence with almost no vegetation produces a lot, but they presumably pay only based on their limited water use. It is also only fair that those who use the roads and the state and commercial parking lots in the metro area pay for the treatment needed for their runoff, but apparently they don’t, the burden is disproportionately on low income urban area renters, many don’t even have a car to use those parking lots while those rich shoreline property owners down the Bay who get the full benefit and who use those roads and parking lots pay almost nothing!