Dousing Ourselves and Mother Nature With Poisons Isn’t Sustainable

Dandelions, grubs, and pans that stick aren’t your enemy

March 13, 2024

Every year, over and over again, Rhode Island drenches itself with multifarious amounts of poison. But it’s not just a Little Rhody problem. It’s a nationwide and worldwide pandemic of madness.

The Rhode Island Department of Transportation annually applies thousands of gallons of herbicide, diluted by water at various ratios, to public lands across the state.

These poisons are often applied in a haphazard manner. RIDOT spraying logs, for instance, seldom note what targeted plants are being poisoned by what herbicide, or note the herbicide applied but not the amount used.

Keeping troublesome invasives, such as multiflora rose and oriental bittersweet, at bay is important for native plants and animals and for roadside maintenance.

But blasting Rhode Island’s 1,100 miles of state roads, highways, and bridges with poison fired carelessly from truck-mounted sprayers comes at a cost, for both human well-being and environmental health, especially when other state agencies, municipalities, landscapers, farmers, property owners, and backyard gardeners are indiscriminately spraying herbicides, insecticides, and all kinds of other -cides.

The health impacts spread by ticks and mosquitos — Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, powassan, ehrlichiosis, West Nile virus, eastern equine encephalitis, and the Zika virus — should be taken seriously, but so too should our persistent use of toxic chemicals to kill them.

The poisons used to kill ticks and mosquitos are part of a cocktail of chemical pollution, including lawn-care pesticides and fertilizers, that threaten the stability of global ecosystems upon which humanity depends, according to a 2022 study.

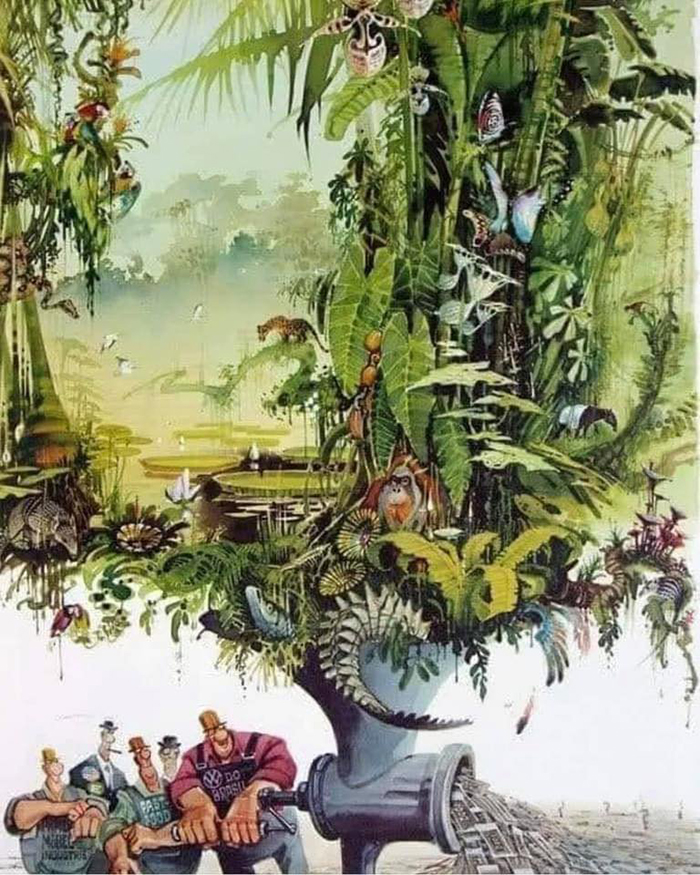

Nature would keep their numbers in check if we weren’t constantly grinding it up for profit and hollow convenience.

RIDOT’s historical herbicide of choice has often been dicamba, which was introduced to U.S. agriculture in 1967. It’s on the Environmental Protection Agency’s list of restricted-use pesticides, meaning it’s more highly regulated and requires training to apply.

Dicamba-based herbicides “have the potential to cause unreasonable adverse effects to the environment and injury to applicators or bystanders without added restrictions,” according to the EPA.

In the first week of February a federal judge in Arizona banned three dicamba-based herbicides widely used in U.S. agriculture, finding the EPA, which has warned about their use, broke the law in allowing them to be on the market.

The ruling is specific to a trio of poisons that have been blamed for millions of acres of crop damage and harm to endangered species and the environment across the Midwest and South.

This is the second time a federal court has banned these poisons since they were introduced in 2017. In 2020, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued its own ban, but a few months later the Trump administration reapproved the toxic products.

Pregnant women in Indiana, a farm state, are showing a fourfold increase in the amount of the toxic plant-killer in their urine, a rise that comes alongside climbing use of dicamba-based poisons in agriculture, according to a recently published study.

The study, led by Indiana University, showed that 70% of pregnant women tested in the Hoosier State between 2020 and 2022 had dicamba in their urine, up from 28% from a similar analysis for the period 2010-12.

Glyphosate has also been used regularly by RIDOT. Glyphosate is among the most widely used herbicides in the United States. It was popularized as the main ingredient in Monsanto’s controversial Roundup products.

Glyphosate poses a broader range of health risks than dicamba, according to some health experts. Research has shown that the chemical, first registered for use in the United States in 1974, is an endocrine (hormonal) disruptor. It’s been classified as probable carcinogen. Prolonged exposure to glyphosates in drinking water can lead to kidney and reproductive difficulties, studies have shown.

New research has found childhood exposure to glyphosate is linked to liver inflammation and metabolic disorder in early adulthood, which could lead to liver cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease later in life.

Besides being a popular herbicide in the United States, it’s also commonly used in Europe. It’s been found in 45% of Europe’s topsoil, and in the urine of three-quarters of Germans tested. In the United Kingdom, glyphosate residues have been found in biscuits, crackers, and breakfast cereals and in 60% of breads.

Since glyphosate was introduced five decades ago, enough of this enzyme-blocking herbicide has been applied worldwide to cover every cultivated acre of land in the world with a half-pound of the poison. Yikes.

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management also applies a variety of pesticides to waterbodies and public lands. For example, the golf course at Goddard Memorial State Park — a nearly 500-acre park along the shores of Greenwich Cove and Greenwich Bay in Warwick — is routinely sprayed with fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides to kill broadleaf weeds, brown patch, crabgrass, goosegrass, grubs, and stinkhorns.

In Rhode Island, manufacturers are required to register their pesticides annually with DEM before their products can be sold or used in the state. Pesticides used in Rhode Island fall into two categories: restricted use and general use. General-use pesticides can be purchased over the counter and require no level of training.

There are between 7,000 and 9,000 pesticides registered in the state annually, according to DEM.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has determined that the federal government has allowed most pesticides onto the market without a full set of toxicity tests, thanks to a loophole called a conditional registration. As many as 65% of more than 16,000 pesticides have been approved using this loophole, according to the New York City-based nonprofit.

About a billion pounds of pesticides are used annually in the United States, according to Beyond Pesticides. While herbicides, insecticides, algaecides, and fungicides can selectively target species, they seldom discriminate against what they kill, meaning, for example, insecticides also kill pollinators and other beneficial insects. These poisons can also make wildlife sick, and they can put human health at risk.

Late last year an analysis of conventional baby food found nearly 40% contained pesticides. The research, conducted by the Environmental Working Group (EWG), looked at 73 products and found at least one pesticide in 22 of them. Many products showed more than one pesticide. (None of the organic products sampled in the survey contained pesticides. Organic food costs more, because we don’t subsidize health.)

Last spring the Agricultural Labeling Uniformity Act was filed in Congress. The proposed measure would provide sweeping protections to pesticide companies and their products, preempting local governments from implementing restrictions on pesticide use.

The Guardian reported that lobbying disclosure records show Bayer and the industry-funded CropLife America have made passage of the bill a priority.

Many pesticides contain persistent organic pollutants. They accumulate in the fatty tissue of humans and wildlife. These human-made poisons saturate the planet, mixing with each other, other human-crafted killing concoctions (such as white phosphorus and the millions of pounds of rat poison used annually in the United States alone), the sun, and water in ways we don’t understand.

I, for one, don’t find comfort living in an uncontrolled chemical experiment being run by the Swedish Chef.

Fire hose of toxicity

Sadly, pesticides are just a ripple in the tidal wave of human-manufactured poisons engulfing us. And those who profit from their sale and the regulators they buy don’t want to crimp the toxic fire hose.

The chemical industry spent $110 million during the past two election cycles paying lobbyists to kill dozens of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) legislation and to slow administrative regulation around “forever chemicals,” according to an analysis of federal lobbying documents published in November.

The industry got its money’s worth, as only eight pieces of legislation that targeted the toxic chemicals made it through Congress, according to the 19-page paper prepared by Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit.

PFAS are a class of some 15,000 compounds used to make products resistant to water, stains, and heat. They have been linked to cancer, high cholesterol, fetal complications, weakened immune response, elevated blood pressure during pregnancy, and liver, kidney, cardiovascular, and thyroid disease.

“As the dangers of PFAS became public and legislative efforts to regulate PFAS and fund remediation grew, so too did lobbying by the chemical industry,” according to the analysis. “The chemical and associated industries are powerful and have used their army of lobbyists and campaign finance war chests to thwart meaningful action.”

About 70 million people are exposed to these toxic compounds in U.S. drinking water, according to EPA testing.

But the testing completed to date has only examined about a third of the country’s public water systems, meaning the federal agency is on pace to find some 200 million people are exposed, or at least 60% of the population, according to a recent story in The Guardian. (Those numbers don’t include private wells, and the EPA has estimated about 8 million people who draw water from those are exposed to PFAS.)

Last summer the Rhode Island Department of Health issued “do not drink” orders to three different water systems because of PFAS contamination above 70 parts per trillion (ppt). Another eight Rhode Island water systems tested above 20 ppt.

Monitoring shows that virtually all people living in the United States have some level of PFAS in their bodies and that “we are exposed through many routes, including our drinking water, food, consumer products, soil, and air,” according to a 2021 NRDC report.

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is a volatile organic compound commonly used in carpet cleaning treatments, hoof polishes, brake cleaners, pepper spray, and lubricants. The toxic chemical is a carcinogen and a liver toxin, harms male reproduction, causes neurological damage, damages kidneys, and causes Parkinson’s disease.

The Obama administration proposed strong limits on its use in 2016, but the Trump administration suspended the process.

Recent EPA research has found that as much as 250 million pounds of TCE are still produced in the United States annually, and much of that poison ends up in water used for drinking, bathing, swimming, and fishing.

A 4-acre site in Johnston on Peck Hill Road near the Scituate border is known to have been contaminated with TCE and other pollutants that contaminated wells in the area decades ago.

The property may again be threatening public health, this time through vapor-forming solvents possibly entering nearby homes and businesses, according to a recent story in The Providence Journal.

Most of the 86,000 consumer chemicals registered with the EPA have never received vigorous toxicity testing, according to a September story in The Guardian.

Regulators also often side with business interests even when a product is found to be hazardous to public health and the environment, because profit over people rules.

Last month the EPA again approved the use of a toxic herbicide linked to Parkinson’s disease. The agency’s recent decision is the latest salvo in a decades-long battle over the use of paraquat. About 60 countries have banned what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls a “highly poisonous” herbicide. Paraquat, which was first produced for commercial purposes in 1961, is on the EPA’s restricted-use list.

About 8 million pounds of this highly poisonous chemical are used annually in the United States. Its use tripled between 2008 and 2018.

A little-heard-of pesticide linked to reduced fertility, altered fetal growth, and delayed puberty has been found in 92% of oat-based foods sold in the United States, according to a study published last month.

Chlormequat was detected in 77 of 96 urine samples taken between 2017 and 2023, with levels increasing in the most recent years, according to the EWG research.

“Our tests found higher levels and more frequent detections of chlormequat in the 2023 samples, compared to those from 2017 through 2022, which suggests consumer exposure to chlormequat could be on the rise,” EWG said.

EPA regulations allow chlormequat to be used on ornamental plants only, not food crops, grown in the United States. Since 2018, however, the chemical’s use has been allowed on imported oats and other foods sold across the country, and the EPA is now considering allowing the use of chlormequat on barley, oat, and wheat grown in the United States.

When applied to oat and grain crops, chlormequat alters a plant’s growth, preventing it from bending over and thus making it easier to harvest. Convenience over human health.

While the federal government is purposely slow to counter this flood of poisons, the U.S. military is annually drowning us in an estimated 500 tons of chaff. Chaff is an electronic countermeasure designed to reflect radar waves and obscure planes, ships, and other assets from radar tracking sources.

It consists of aluminum-coated glass fibers ranging in length from 0.29 to 0.31 inches. Chaff is released from military vehicles in cartridges or projectiles that contain millions of these fibers. Most of those 500 tons are released during training exercises within the continental United States.

The odds of a U.S. resident dying of cancer is 1 in 7, while the odds of dying in a terrorist attack is 1 in 3.5 million.

As for other bits of nastiness we ceaselessly manufacture without thought, preclinical studies have found that microplastics and nanoplastics are emerging as a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Polyethylene, the most commonly produced plastic, was detected in carotid artery plaque of 150 patients, or 58.4%, of those examined, according to a March 7 study.

“Electron microscopy revealed visible, jagged-edged foreign particles among plaque macrophages and scattered in the external debris,” the authors wrote.

Their presence was linked to a subsequent 4.5-fold increase in heart attack and stroke.

Note: For those unfamiliar with the Swedish Chef, shame on you. Here’s a link.

Frank Carini can be reached at [email protected]. His opinions don’t reflect those of ecoRI News.

We need to have laws stating the precautionary principe. Unless you can prove something is safe, do not let it onto the market and into the public spaces at all. our current practice seems to be let everything loose and itf it kills enough people sue to get it off the market. We are collectively homicidal maniacs.

What does it take to get products like Roundup off of the shelves in Rhode Island stores

The World Health Organization has stated that Rounding is a known carcinogen. What about all the pesticides that are decimating our bees and other pollinators

Are our regulators asleep at the switch or is it something more sinister

Why can’t they safeguard our environment. They are called Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management what exactly are they managing.

Could it be profits for pesticide manufacturers.

I Hope not.

Great info Frank Carini!

But some consumers demand picture perfect lawns and the hardware stores have shelves of chemicals.

Time for an environmental levy for toxic chemicals or outright ban for many?

Time to make the little lawn chemical application signs list the chemicals used near public property and leave them up for 10 days? And post more than one sign!

great column Frank with lots of info. An example of why we support ecori!

Even though I’ve followed transportation issues here a long time I didn’t know about RIDOT’s roadside chemicals (except for salt to control snow and ice which also sees into the water supply.) I thought they planted billboards.

And I like dandelions, just saw my first this spring with bright cheerful yellow, if they crowd out a bit of boring grass I don’t mind