Brown University Students Examine How Noise Pollution Disproportionately Affects Some Providence Neighborhoods

December 11, 2022

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Imran Dharamsi, a junior at Brown University, was a little bit shocked the first time he walked over the India Point Park Bridge and heard the rush of traffic.

“I’ve never been to a park that’s just that loud because there’s a six-lane highway right there,” said Dharamsi, who went to high school in rural Pennsylvania.

That astonishment was something that inspired Dharamsi’s project for a class exploring noise pollution in Providence, taught by Erica Walker, assistant professor of epidemiology.

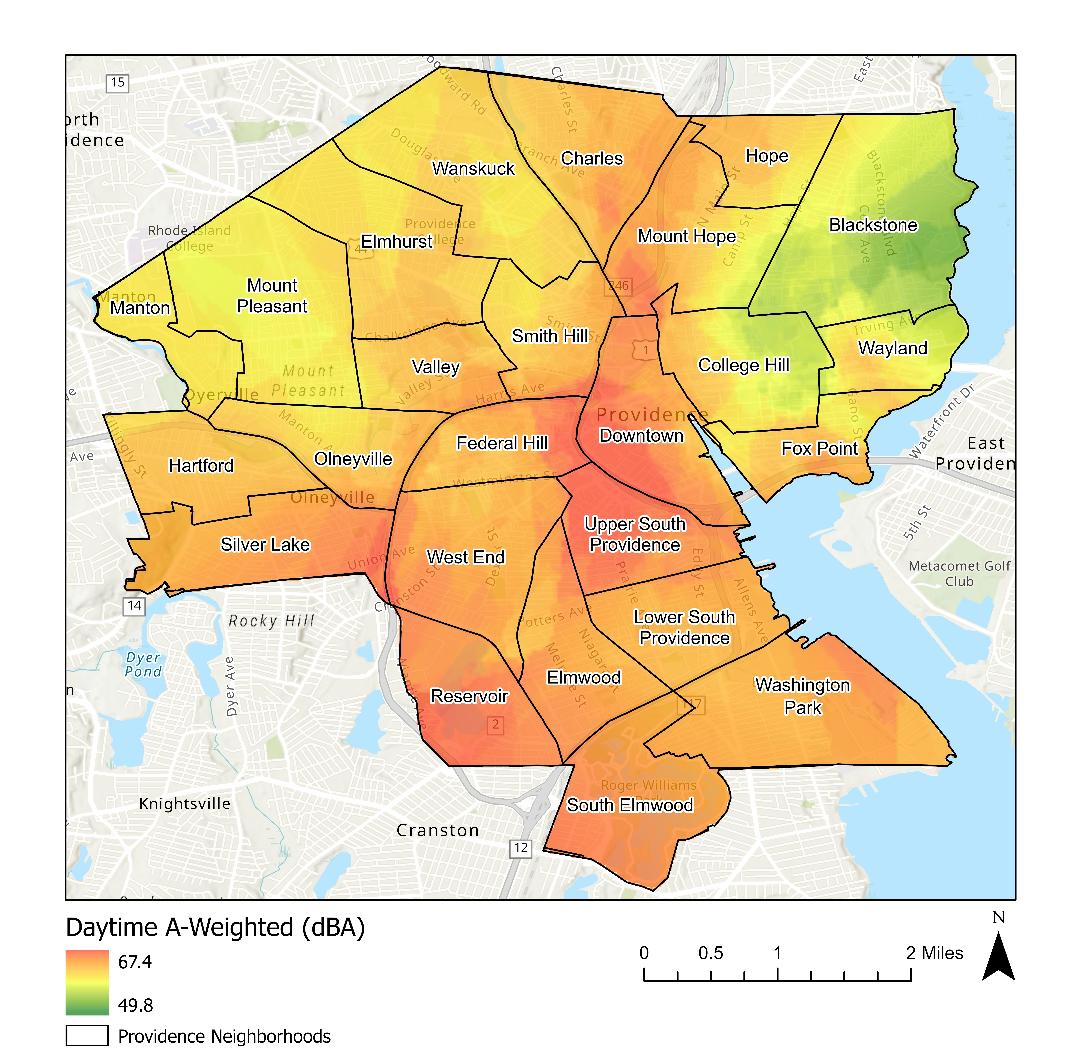

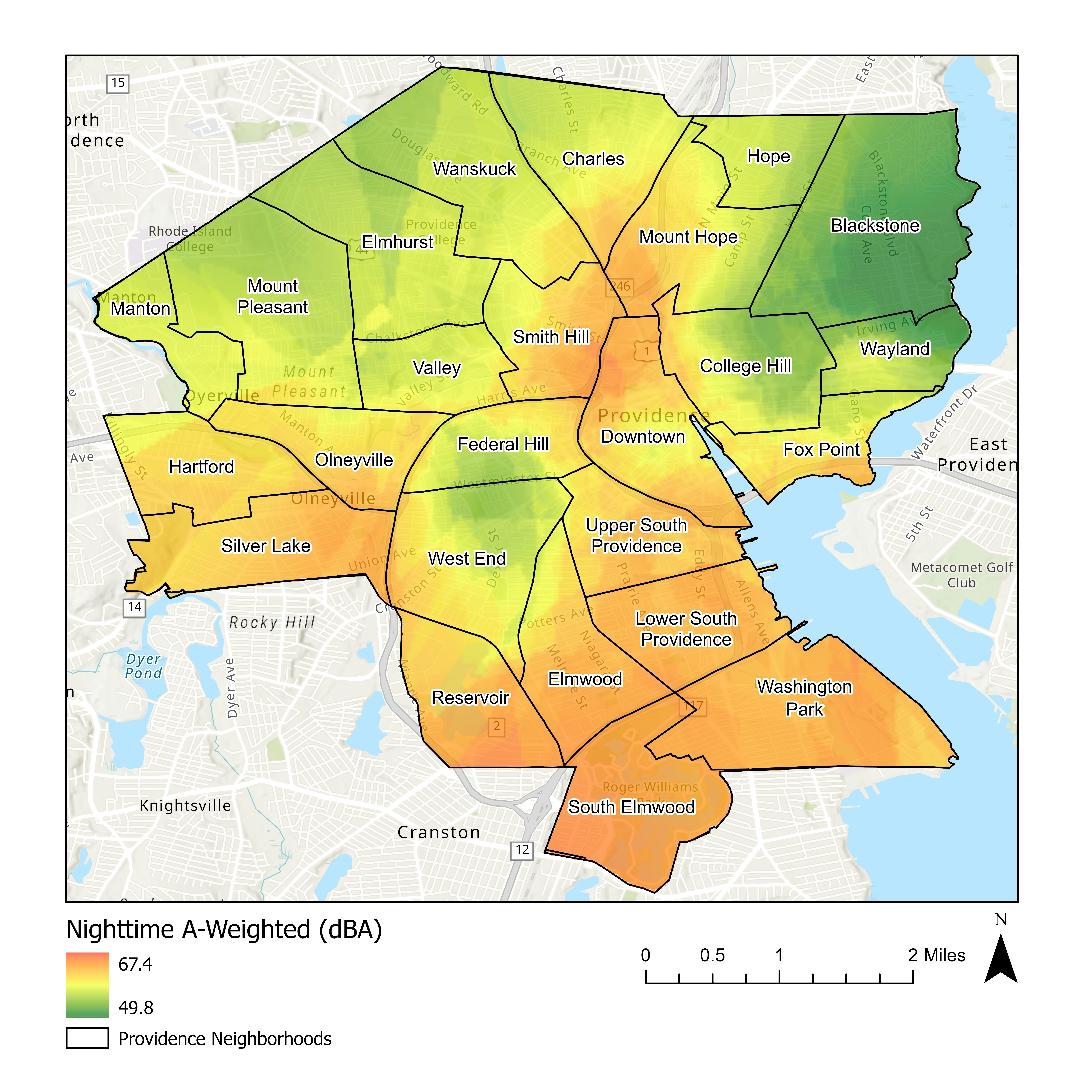

Dharamsi and the rest of Walker’s class, called “Environmental Exposure Assessments in Practice,” tested sound levels in 180 sites around the city during the semester. Their findings created a noise heat map and “report card” for Providence that highlights the disparities in noise pollution, which can have serious physical and mental health impacts.

In the areas around highways and in neighborhoods with more non-white and low-income residents, students in Walker’s class found noise pollution levels were higher — sometimes above the maximum decibel levels set by city ordinances.

The heat maps the class created show South Elmwood and upper South Providence are the loudest neighborhoods, while the College Hill and Blackstone neighborhoods are the quietest. It also shows the difference between daytime and nighttime noise, which quiets only slightly in some neighborhoods at night.

Before the students started taking noise samples, they wrote abstracts to explain what aspects of noise pollution they wanted to investigate and why they had chosen their sampling sites.

Students then traveled around the city — Dharamsi had to borrow someone’s car after he realized walking across Providence wouldn’t work — to collect noise samples using research-grade sound level meters.

“We used equipment that could hold up in a court of law,” said Walker, knowing the data would be shared with community members and decision-makers.

The data points for each location represent samples taken from a day and night on a weekday and day and night on a weekend.

After collecting his data from 10 sites near highways and five sites near residential areas, Dharamsi found the average decibel level near highways was lower than the daytime noise limit set by the city but higher than the nighttime maximum.

Using U.S. Census data, Dharamsi was also able to discover that among his sample sites, areas that had 10% higher proportion of white residents were about 1.6 A-weighted decibels quieter (A-weighted sounds are within the range that the human ear is most sensitive to).

Dharamsi explained that this is mostly because people of color tend to live near highways, which are louder, even at night.

Other projects in the class, like one done by Orly Richter, also looked at the difference between areas of the city with more high- and low-income residents and more residents of color versus white residents.

Richter’s study examined sites on bus routes and showed “significantly higher sound levels in areas with lower median household incomes, lower percentages of white residents, higher percentages of Black residents, and on bus routes, meaning that people living or spending time in these areas face greater sound exposure.”

Another study done by Malcom Johnson analyzed areas impacted by redlining and found that places where more Black residents lived were about 10 decibel units higher than the areas that they’d been historically excluded from.

“The findings extend previous research that links disproportionately adverse environmental exposure to historically marginalized people and communities,” Johnson wrote in the study’s abstract.

These disparities are distressing because noise pollution can impact the health of those who experience it, Walker said.

Walker likened hearing loud noises to the feeling of preparing to flee from a predator, prompting the release of stress hormones, which trigger sweaty palms, a churning stomach, and a pounding head, she said.

“That constant stimulation of that fight or flight response can lead to the manifestation of really pretty serious diseases,” she said.

Noise pollution can also disrupt the quality and quantity of a person’s sleep, which can cause major health disturbances, and it can take a toll on mental health, Walker added.

Dharamsi, who is double majoring in economics and public health, said this research followed other academic work he’s done, including work on the relationships between community safety and safe injection sites, and car stops and fatal crashes, which shows structural issues and inequity.

Although it might be difficult to change where and how a highway operates, Dharamsi said one “Band Aid” solution to reducing noise pollution could be offering soundproofing equipment to residents living close to those major roads.

“It’s not a perfect solution,” he said, but added, “we need to do something, given how high the sound levels are.”

“I told students in the class that we’re not necessarily in the business of telling people what to do,” Walker said. “I kind of do public health as a tool to make sure that everyone, regardless of their socioeconomic status, [is] able to choose from a basket of goods that maximizes their quality of life and health and well-being.”

She hopes the students’ work will be something decision-makers are aware of and think of when they decide where to put highways or zones for entertainment and nightclubs or any effort that could affect the noise levels in a neighborhood.

“We hope that our findings will allow people to think about those things when they’re planning their cities, when they’re determining where things go, who gets helped the most,” she said.

Colleen Cronin is a Report for America corps member who writes about environmental issues in rural Rhode Island for ecoRI News.

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsRecent Comments

Leave a Reply

Related Stories

Your support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings

The map is a bit misleading when one thinks about how much noise people are exposed to as hundreds of acres in the Blackstone neighborhood have zero people living there. The quietest place is a cemetery.

Planting more trees could help with sound dampening. Higher density of people typically leads to more vehicles on city streets too. One triple decker can equal 3-6+ vehicles. If the property owner paves to create parking, one will also lose some green sound buffer. I would appreciate if all the cities stepped up the tree – green planting where it can happen.

besides possible noise abatement grants noted solutions could include: more + incentives for quieter electric landscape equipment and for quieter vehicles including electric cars, electrifying the commuter rail, noise ordnance enforcement, especially on trucks and motorcycles, reduced speed limits in affected areas.

Maybe look into what was done around the airport where noise is also an issue.

I also note in the 1970s Congress passed a Nosie Control Act that the EPA was supposed to administer, but when Reagan became President he had that program dropped

Double down and overlay noise pollution maps on a map with light pollution and I bet the similarities are starkly similar. Areas with high light pollution levels probably also have high nose pollution levels as well. Now, compare the associated health risks with both pollutants acting as stimulates to the living populations there and trend hospitalizations, cancer rates along with other health factors and I bet it’s easy to conclude all these artificial, man made pollutants are significantly impacting society. Good read, great research study and I hope the results can be used to effectuate positive change.

I wonder about noise levels in classrooms and their effect on learning.

I’m pleased to see this is becoming such an important topic in many places. Kcinri6876 does well to add light pollution, but the one thing I don’t see addressed is that noise–and light–pollution don’t stop at town borders. Pawtucket is allowing a truck distribution center to be built just over the town line from Providence. The noise, light, and air pollution from this plant (my research tells me that such centers world wide are the third leading cause of lung chancer) will affect Providence as much as it will affect the remaining play/green space next to the center and the people in the elementary school half a mile away.

After seven good years and one very bad year living of Federal Hill in Providence, we sold our house there. The unbelievably loud and uncontrolled noise the city allowed to proliferate in neighborhoods, which came from commercial establishments (licensed by the city) drove us out of Providence. My husband, an engineer, informed the Board of Licensing that sound travels great distances, especially when it travels uphill. We were hearing loud music from across the highway, and from as far away as 1,500 feet, though the legal limit is 200 feet! Many residents joined us in signing petitions and attending Board of Licensing meetings to ask that the law be followed, but nothing was ever done. The BOL was told repeatedly that the sound levels were unacceptable, yet residents were left to suffer long nights of thudding windows and high decibel music and shouting.