Balancing Housing with Protecting Water Resources Requires Smart Approach

April 10, 2023

Human activity on land is directly tied to water quality and the resource’s availability. How a property owner uses or abuses her land can impact a neighbor’s drinking water well. Land-use decisions at the municipal level can impact coastal salt ponds. Building more housing in the wrong location can drain an aquifer.

With the demand for housing outpacing availability, southern New England, like many other regions of the country, is facing a housing crisis. Rhode Island’s lack of affordable housing has been called a crisis by both lawmakers and government officials. In the Ocean State, however, most of the new housing stock developed has so far been built with the wealthy in mind — second homes, McMansions, and grandiose dwellings. Much of the state lacks affordable housing.

How municipalities respond to the demand for housing has significant consequences not only on community character but also residents’ quality of life and the resources they depend upon for their drinking water, livelihood, and recreational pursuits.

An early March webinar sponsored the SNEP Network explored the approaches being used in Rhode Island to support growth and housing density while also protecting water resources, both surface and ground.

The hour-long presentation — by Scott Millar, director of conservation and community assistance for Grow Smart Rhode Island, and Lorraine Joubert, program director Rhode Island Nonpoint Education for Municipal Officials — focused on the unintended impacts to water resources resulting from development; described state-adopted approaches to supporting growth and housing density while also protecting water resources; and identified the reasons why municipal adoption of certain regulations to protect water and other natural resources is critical and where housing density is appropriate.

They noted the region’s housing needs can be met without impacting water quality. The key is creating more housing, affordable or otherwise, without diminishing a vital resource.

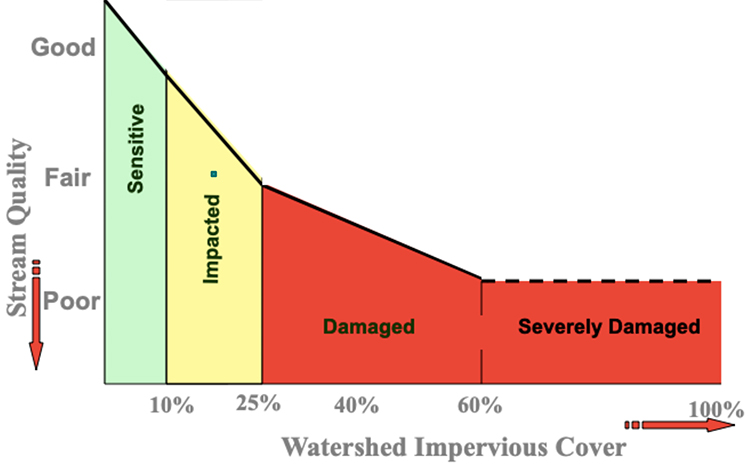

Millar began his presentation by noting an increase in housing density equals a decrease in water quality, and since polluted waters are expensive to restore, he said, prevention is critical.

State regulations alone are inadequate to protect water quality, according to Millar.

“That’s not a function of the weakness of the regulations or the people that administer them. They’re as good as they’re gonna get,” Millar said. “The issue is that the state cannot control density or the type of use. Therefore, municipal use is critical to supplement state regulations to protect water quality.”

To balance the need for more housing while also protecting water quality requires smart-growth techniques, such as minimizing impervious cover and keeping development away from sensitive areas like wetlands, the coastline, riverbanks, and lakes.

Joubert noted the negative impact stormwater runoff, carrying pollutants — hydrocarbons, chemicals, fertilizers, pesticides, dog poop that was irresponsibly left behind — from roads, highways, driveways, rooftops, other hard surfaces, and even lawns, can have on water quality.

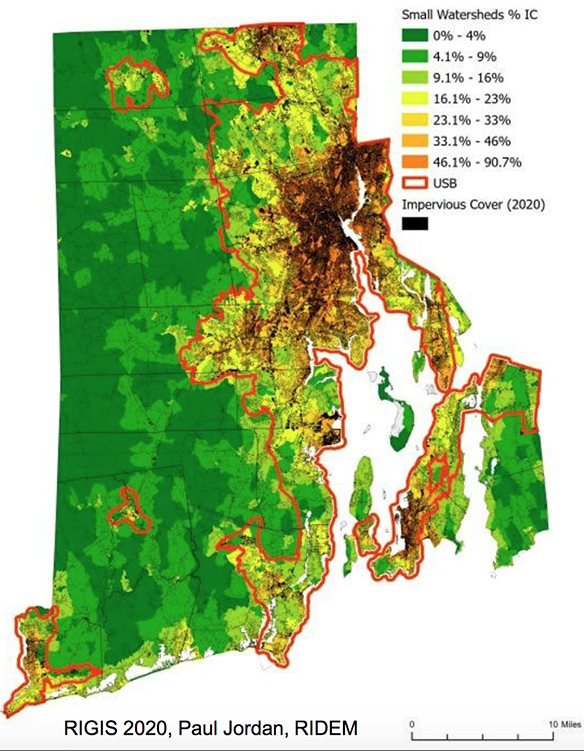

“We’re beginning to see water quality impacts in fresh waters … rural areas of the state that we’ve considered pristine and have not had problems before,” she said.

Among the waterbodies Joubert mentioned that are now being impacted by nutrient enrichment that fuels algal blooms is the eastern end of the Scituate Reservoir where the water is shallower. The Scituate Reservoir, the largest freshwater body in Rhode Island, supplies about 60% of the state with its drinking water.

Some municipalities, such as Charlestown, have done a lot of work to remove cesspools, which offer no protection from or treatment of waste, and repair failing septic systems to help better control nutrient enrichment to nearby waterbodies, most notably South County’s popular salt ponds. But, as Joubert explained, housing density remains a problem.

“Charlestown has actually eliminated all but two cesspools in the entire town, which is incredible,” she said. “So they continued groundwater monitoring to see the impact and it’s very discouraging but the groundwater nitrate levels continue to increase despite all the improvements they made — and that is based on density. There’s no other explanation. Density with increased development on small lots, often times with pretty large houses.”

Ban chemicals on lawns too.

Build up not out.

Agree with Greg’s point.

Saying that housing density leads to degraded water quality- drinking water, fresh and salt ponds, while having truth based on practices of today, seems to limit what we can do to add needed housing in much of the state….like giving greater density bonuses to quality housing with the greatest need and shortage-for low to extremely low income households….and through limiting use of water for watering lawns…..restricting fertilizer and enforce proper maintenance of septic systems-especially advanced ones and those in critical locations…..enforcing proper maintenance of stormwater control systems…..limiting impervious surfaces….and other steps ?… can we develop practices that limit point and non-point pollution in residential developments and protect natural resources in parts of the state that have the most conservation land, the least degraded lands and water resources and the least contribution to the affordable housing crisis……..

….edit last line, above, to ….least contribution to solving the affordable housing crisis

Charlestown needs to ban asphalt residential driveways. Some are now putting down asphalt and covering it with shells or pea gravel. In areas where there is high density this causes more run off.