Toxic ‘Forever’ Chemicals Pose Risks to Rhode Islanders

Efforts to raise awareness about dangers of PFAS continue

July 27, 2020

In the United States, 98 percent of the population has detectable levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in their bodies. These manufactured chemicals linked to cancer coat food packaging that resists oil, such as microwave popcorn bags and some pizza boxes.

While some of the more dangerous PFAS (PFOA and PFOS) are no longer manufactured in the United States — they are still produced internationally and can be imported in consumer goods — there are thousands of related compounds in wide use and the number is expanding rapidly. There may be as many as 3,000 on the market today.

Most of these man-made chemicals are protected by trade secrets, and their impacts are largely unknown.

Your non-stick frying pan may be PFOA or PFOS free, but like labels that read “BPA Free,” there are thousands of chemicals that are structurally related and could produce similar health problems. For example, little is known about replacement substances such as GenX. Preliminary studies suggest that they react in the body in the same way as PFAS.

That is why there is a need to regulate the entire tree of these related 5,000 to 10,000 compounds, according to those who spoke at a recent online panel discussion about the dangers of PFAS and related substances.

The July 22 event, hosted by Clean Water Action Rhode Island, the Conservation Law Foundation, and Reps. Terri Cortvriend, D-Portsmouth, and June Speakman, D-Warren, featured Terry Gray, deputy director of environmental protection at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM); Angela Slitt, director of graduate programs at the University of Rhode Island’s College of Pharmacy and co-lead of the school’s Sources, Transport, Exposures & Effects of PFAS; and Craig Howard, who worked on the research study featured in the film Dark Waters that showed the devastating effects of PFAS on DuPont employees and the residents of Parkersburg, W.Va.

Gray said these chemicals are a problem in Rhode Island, even though there are no DuPont plants here. He noted that PFAS are pervasive.

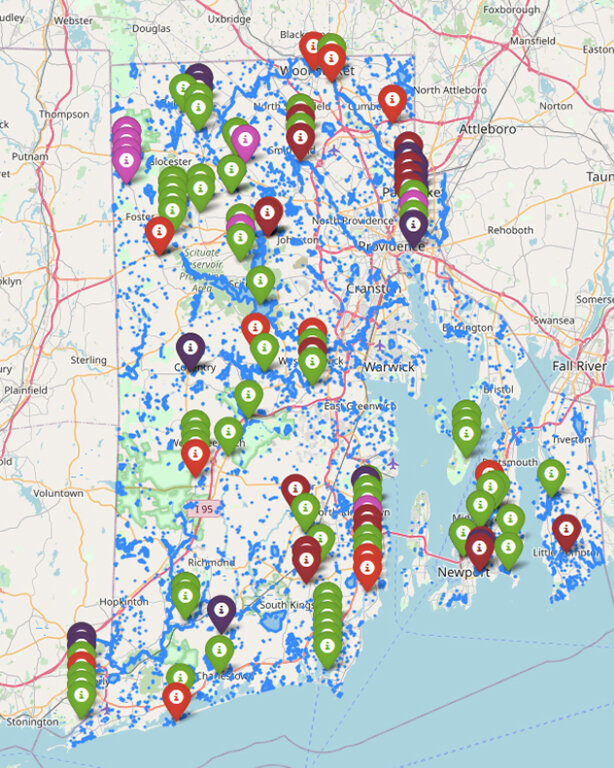

The Rhode Island Department of Health tested for PFAS last year. The agency tested every major drinking-water supply in the state and the water in every school that had its own well. In all, 87 percent of Rhode Islanders had their primary source of water tested. The results showed that PFAS are in a significant portion of the state’s drinking water — they were detected in 44 percent of the locations tested — and that more than 40 percent of the schools tested had levels above the new recommended standard of 20 parts per trillion (ppt). The Environmental Protection Agency originally issued a 70 ppt health advisory level, but since then a growing number of public-health officials and some states are pushing for levels of 20 ppt or lower.

In Rhode Island, House and Senate versions of the same bill would require municipal water systems to treat their drinking water or offer an alternative source if levels exceed 20 ppt. Last year, New Hampshire adopted rules that established drinking-water standards for four PFAS chemicals of 12 ppt. The state was quickly sued by industry behemoth 3M.

In 2017, just weeks after the Oakland Village Water System in Burrillville was awarded “Rhode Island’s Best Tasting Drinking Water” by the Atlantic States Rural Water & Wastewater Association, DEM discovered the water was contaminated with PFAS.

PFAS used in firefighting foam are blamed for the closure of the Oakland Village Water System and several other private wells in the area. The fire suppressant is also the likely source for massive concentrations in wells at the Quonset State Airport in North Kingstown. PFAS-containing firefighting foams were commonly on hand and used anywhere fuels were stored, including airports and military bases.

Newport’s Naval Education & Training Center stored hundreds of millions of gallons of fuels and had firefighting foams on site. The Melville area of Aquidneck Island has been a fuel depot since World War I. There was a recent proposal to convert the site to a commercial marina, but the discovery of PFAS halted the project. A cleanup is ongoing.

Bradford Dye, now bankrupt, was a facility that manufactured battle dress uniforms and chemical suits for the Department of Defense. The plant left hundreds of PFAS-contaminated drums and highly contaminated lagoons adjacent to the Pawcatuck River, which, along with the Wood, is designated a wild scenic river and is a valuable natural resource for both Rhode Island and Connecticut.

Slitt noted that PFAS accumulate in the liver, and it takes four to five years for the human body to remove just half of these chemicals. According to research, PFAS cause increased cholesterol, a decrease in vaccination effectiveness, liver damage, and decreased birth weight. New data even suggests that PFAS leave humans more susceptible to the coronavirus.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident.