More Money Approved to Replace Region’s Lead Water Pipes

April 27, 2020

Progress is being made in southern New England on the long-running struggle to replace lead water pipes, both on the public and private side.

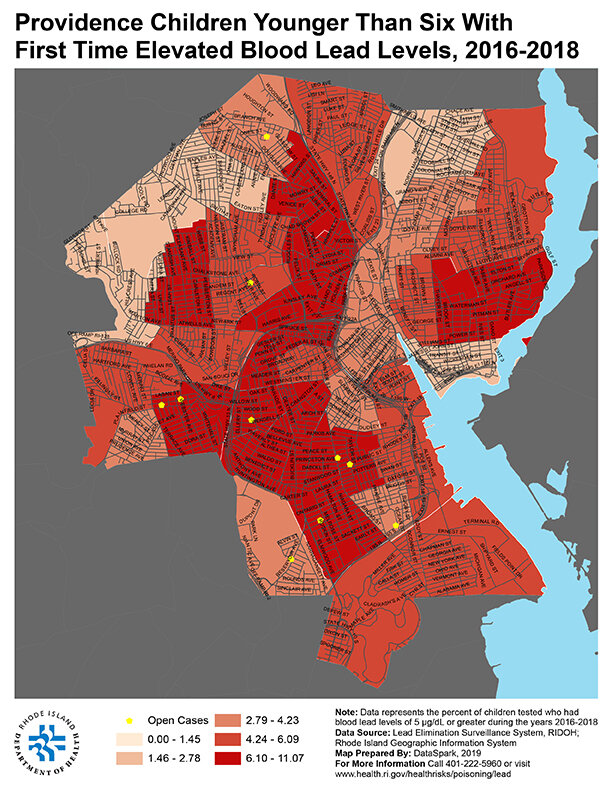

The region’s old housing stock and water-service infrastructure are riddled with lead pipes and fixtures that are blamed for numerous ongoing health problems. For children, in particular, lead exposure damages the nervous system, causes learning disabilities, inhibits growth, and impairs hearing.

The problems have been known for decades, but it wasn’t until 1986 that the United States banned lead service lines and lead solder used for plumbing. Awareness of the risks has prompted water utilities to remove lead infrastructure that runs from reservoirs to water mains, which are not made of lead.

But the pipes that connect water mains to homes and businesses, known as service lines, have remained. Providence Water, the state’s largest water utility, stopped installing lead service lines in 1945. Yet today, about one out of every six of its customers have service lines made of lead. Most are located in Providence and Cranston. Some are in Johnston and North Providence. Providence Water customers can use this online map to learn if they have lead service lines. All other municipal water suppliers should know which customers are using lead pipes. Water testing by local labs can also identify lead contamination from internal plumbing.

Paying to get rid of service lines has been a challenge. Various loan programs and tax incentives help property owners absorb the costs, but progress is slow. For instance, only a few hundred of Providence’s 28,000 private-side lines made of lead are replaced each year. Since 1996, Providence Water has replaced approximately 18,600 public side lead service lines.

A recent study of the Washington, D.C., water system by the Environmental Defense Fund found that wealthy households are taking advantage of pipe-replacement incentives, while low-income and minority households are less likely to make the switch, further increasing public-health problems.

“The practice puts low-income households in a difficult position — either they pay to avoid a partial LSLR [lead service line replacement] or their families are at an increased short-term risk of exposure,” according to the study published last month.

The study also found that posting online interactive maps showing the location of lead water pipes triggered a 75 percent increase in permits for pipe removal. The study recommended that water customers receive notification of pipeline repairs or infrastructure work near their property so that replacement can be done simultaneously, often at a discount.

Water districts have resisted the most comprehensive approach: having ratepayers foot the bill to replace private-side lead service pipes. Unlike other water districts, Providence’s private service lines are technically owned by the property owner.

This year, however, the Providence Water Supply Board, the city-owned manager of the Scituate Reservoir with 600,000 water customers, put forth a proposal to the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission (PUC) to do just that. The PUC is expected to rule this year on whether Providence Water can increase rates to spend $3 million annually on private-side replacements.

Recently, another $10 million has been freed up, thanks to a temporary federal rule change, that allows states to use a portion of the federal money they receive for clean-water projects to pay for lead-pipe-related projects. In January, the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank (RIIB) approved a $19.1 million loan to state water districts to conduct water-main rehabilitation, which includes the replacement of public-side lead service lines.

In the next 18 months, RIIB expects to approve requests for those funds from Providence Water, the Bristol County Water Authority, the Greenville Water District in Smithfield, and the water authority in Newport. The money will pay for reducing the 11,000 or so public-side service lines, or those pipes that connect from the curb to a water main.

Providence Water also received permission to spend $3 million on a loan program that will offer 10-year, interest-free loans to property owners to cover service-line replacement, which can cost between $1,900 and $15,000. The district’s current loan program offers 3-year, interest-free loans, which have an average payment of about $100 a month.

“We’ve got over $20 million of lead work to be done,” said Jeff Deihl, RIIB’s executive director.

These programs and actions in Rhode Island have largely been triggered by Providence Water’s struggles to deliver lead-safe water levels. The Environmental Protection Agency allows a maximum of 15 parts per billion (ppb) of lead in water tests. Providence Water spiked to 30 ppb in 2009 and 2013, and hasn’t stayed below the EPA threshold for consecutive testing periods since 2015.

Under federal regulations water utilities that fail to meet this threshold are required to replace 3 percent of their lead service lines annually. Currently, Providence Water has a target of replacing 7 percent of these lines annually, while giving priority to high-risk ratepayers such as pregnant women and homes with young children.

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsRelated Stories

Your support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings