Rhode Island’s Climate Crisis Means Higher Energy Bills and Less Work

October 8, 2020

The economic damage caused by the climate crisis will impact many industries in different ways. And since these industries have different geographical patterns, the economic damage will affect southern New England’s 27 counties differently.

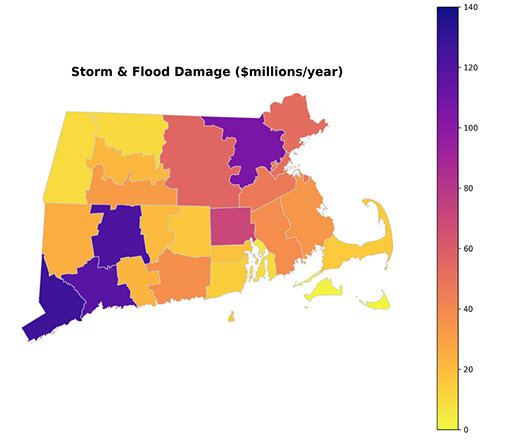

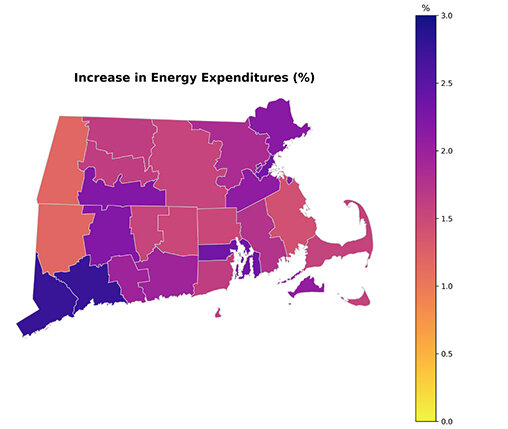

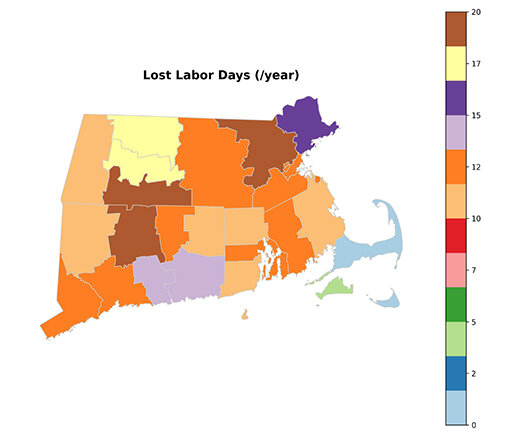

The map to the right and the others below, created using data from a 2017 study titled Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States, summarizes the yearly economic damage, in millions of dollars annually, to the counties in southern New England by the end of the century.

Therefore, in concert with state and national activities, each county will likely need to develop its own specific mitigation strategies. The economic damage will come from many different sources.

Storms and flooding

Southern New England is vulnerable to the coastal impact of hurricanes, storms, floods, and sea-level rise. The total damage to the three states is estimated to average $7 billion to $8 billion annually.

A comparison with the impact of Superstorm Sandy on New Jersey in fall 2012 is useful. Sandy destroyed property worth about $25 billion and decreased New Jersey’s gross domestic product by $12 billion, according to a 2013 report. In the last quarter of 2012, Sandy caused employment losses of 4,200 jobs and a drop in personal income of $1 billion.

Sandy was a once-in-a-lifetime event. By the end of the century, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut could experience a Sandy-level event every two to three years, according to research projections. Rebuilding and recovery from each storm would be completed just in time for the destruction caused by the next storm.

The continued warming of the atmosphere and the oceans is also significantly increasing rainfall and flooding.

Increased energy costs

Global warming will increase the demand for energy. In southern New England, hotter temperatures will mean more summer air conditioning and less winter heating.

While the overall net increase looks small — a few percent — monthly bills will likely increase. By 2050, a 40 percent increase in summer air conditioning costs will only be partially offset by a 35 percent decrease in winter heating cost, according to a 2014 study.

This trend is already clear. In winter 2019-20, heating costs were down about 9 percent compared with winter 2018-19.

For utility companies, the increase in energy demand in the summer will require significant investment in additional capacity and energy-efficiency measures. Capacity expansion in the energy sector requires long lead times. Therefore, little time remains to act on anticipated warming trends.

Lost working days

As temperatures rise, the total number of hours worked declines, as does worker productivity.

About 23 percent of all employed workers are at high risk due to outdoor temperatures. Occupational sectors that will be impacted the most are agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, mining, quarrying, utilities, construction, and manufacturing.

In Rhode Island, workers in the above high-risk categories could each lose two to three weeks per year of work time.

Without action, the economic impact from the climate crisis will likely be devastating. The impacts will be felt in many industries and will be distributed unevenly across geographical areas.

Much of the economic damage will be felt by individuals and families through poorer health, rising energy costs, increased health-care premiums, and decreased job security.

Agriculture

The dairy industry is highly sensitive to temperature changes, as the productivity of dairy cows starts decreasing above 77 degrees Fahrenheit.

As temperatures rise, maple sugar harvests will decline. Maple sugar is currently a $31 million industry that is expected to suffer losses of between 15 percent ($5 million) and 40 percent ($12 million) in annual revenue because of decreased sap flow.

The forest industry will likely face declines in productivity as high as 17 percent. Rising temperatures will change forest composition and the industry will be jeopardized by pests, fire, and extreme weather events. The forest industry employs some 300,000 people in New England and New York.

Public health

Higher temperatures result in increased mortality and this is particularly true in northern cities, where residents are less accustomed to extremely warm weather. For example, the death rate rose 85 percent in Chicago after a five-day heat wave in 1995, followed by an 11 percent increase in hospitalizations.

Warming also contributes to the spread of infectious diseases, because warmer temperatures create ideal conditions for the development of stagnant air masses that reduce air quality and trap pollution. Rising temperatures also increase pollen production and air pollution, both of which aggravate existing respiratory ailments and raise death rates.

The impact on health-care costs will be significant. The costs of adapting to changing health conditions will likely lead to noticeable health insurance cost increases.

Infrastructure

Much of the region’s extensive transportation infrastructure is close to the coast, where it’s vulnerable to severe economic devastation from climate change. This infrastructure includes roads and bridges, water-supply facilities, and energy-supply networks.

In 2004 alone, coastal damage in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions was nearly $4 trillion. A category 4 hurricane touching down in a major metropolitan area could inflict $50 billion to $66 billion in insurance losses alone by the end of the century.

Added to the above storm damage, the economic impact from sea-level rise could add another $8 billion to $58 billion.

Southern New England’s tourism and beach-related sectors, which are primarily located in vulnerable coastal communities, will experience declines. Changes in water quality and water temperature near the coasts will negatively impact the $63 billion ocean economy sector, which employs more than a million people in the region.

Editor’s note: Part 2 of a three-part series about the economic consequences of the climate crisis on Rhode Island. Part 1. Part 3.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at [email protected].