Unsung Infrastructure Protects Nature from Humanity’s Squeeze

Wastewater treatment faces pressures both big (climate) and small (baby wipes)

September 27, 2018

Rhode Island’s rapidly aging wastewater infrastructure is facing growing man-made pressures that go well beyond Nos. 1 and 2. More intense and severe weather, thanks to a changing climate, and wrongly labeled consumer products called “flushables” are causing problems of various sizes.

“It’s the most important infrastructure no one ever sees,” said Bill Patenaude, principal engineer for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Office of Water Resources. “It’s civilization 101 — the greatest boon to public health. This infrastructure got waste away from where you live and the water you drink.”

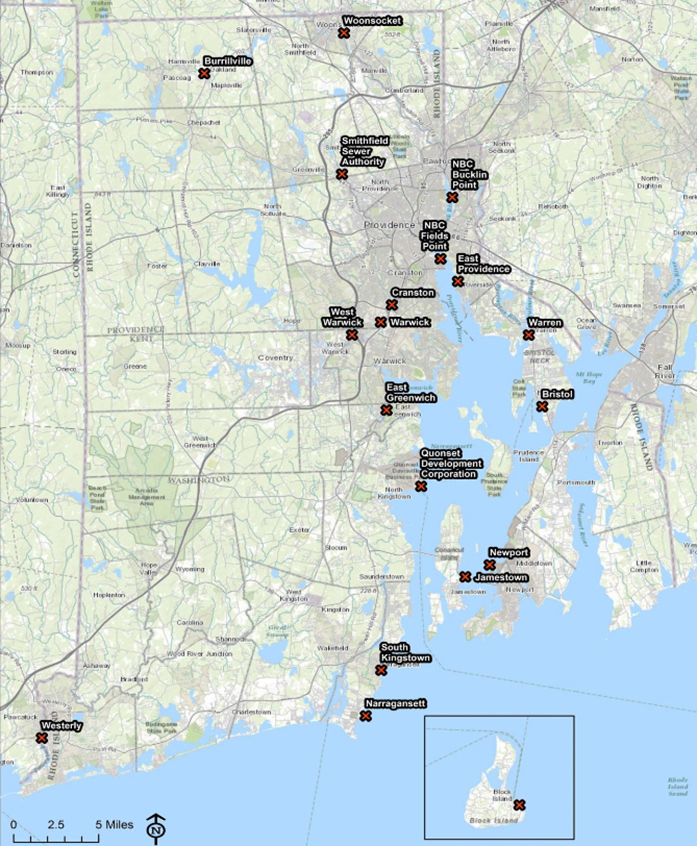

Nationwide there are some 15,000 facilities that treat about 32 billion gallons of wastewater daily. In Rhode Island, there are 19 major wastewater treatment facilities, with 240 pumping stations and hundreds of miles of sewer lines, from a few inches to 9 feet in diameter, that treat 120 million gallons of waste every day. This flow — from residential, commercial, industrial, and septic haulers — never stops, even as system pressures mount.

The state’s collection of wastewater infrastructure also includes smaller facilities and private onsite systems, such as septic systems, both working and failing, and useless cesspools that do nothing to treat waste.

Most of this wastewater infrastructure is underground, making maintenance and repairs difficult and expensive. Much of this infrastructure, which defends the perimeter of Narragansett Bay, is also old.

Here is a brief look at the state’s 19 major wastewater treatment facilities, courtesy of a 2016 DEM document:

Bristol: Built in 1935, serves population of 20,700, and discharges into Bristol Harbor.

Burrillville: 1980, 9,700, Clear River.

Cranston: 1942, 73,200, Pawtuxet River.

East Greenwich: 1927, 6,000, Greenwich Cove.

East Providence: 1952, 46,100, Providence River.

Jamestown: 1980, 2,100, East Passages of Narragansett Bay.

Narragansett: 1965, 7,300, Rhode Island Sound.

Bucklin Point (Narragansett Bay Commission): 1954, 120,000, Seekonk River.

Fields Point (Narragansett Bay Commission): 1901, 226,000, Providence River.

New Shoreham (Block Island): 1977, 300-700 in winter/4,000 in summer, Rhode Island Sound.

Newport: 1955, 41,600, East Passage of Narragansett Bay.

Quonset: 1941, 10,000, West Passage of Narragansett Bay.

Smithfield: 1978, 14,000, Woonasquatucket River.

South Kingstown: 1978, 29,400, West Passage of Narragansett Bay.

Warren: 1951, 8,000, Warren River.

Warwick: 1965, 60,200, Pawtuxet River.

West Warwick: 1942, 31,600, Pawtuxet River.

Westerly: 1927, 16,500, Pawtuxet River.

Woonsocket: 1897, 51,400, Blackstone River.

The Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank invests significantly in wastewater treatment projects, and municipal bonds also pay for vital upgrades. However, maintenance, repairs, and upgrades are becoming more costly and necessary as the climate changes and consumption intensifies. Sewer bills alone can’t fund all of the necessary upgrades and repairs.

The American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2017 Infrastructure Report Card estimates that Rhode Island needs to spend $1.92 billion during the next 20 years on repairs and upgrades to the state’s wastewater infrastructure.

Three years before the historic floods of March 2010 revealed weaknesses in the state’s wastewater infrastructure, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) expressed concerns about Rhode Island’s water quality. The federal agency was particularly focused on eliminating sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs).

“There are numerous reported discharges of untreated sewage from SSOs in New England states, including Rhode Island. Sanitary systems are designed to collect and transport all of a community’s wastewater to a publicly-owned wastewater facility for appropriate treatment before discharge to our nation’s waters,” according to a 2007 EPA letter to municipalities. “Sanitary sewer systems that are not properly designed, financed, operated and maintained, or that lack adequate capacity, result in discharges of raw sewage and industrial wastewater into the environment. EPA has reviewed DEM’s records and determined that SSOs in Rhode Island have resulted in beach and shellfish bed closures, and other risks to public health and the environment.”

The state has since invested in repairing problem areas, but it’s an ongoing battle. For instance, 37 wastewater treatment facilities, including 16 of the state’s major plants, discharge more than 200 million gallons of wastewater into the Narragansett Bay watershed daily. All of this effluent ends up in the Ocean State’s most important natural resource.

Wastewater infrastructure is expensive to build and maintain and difficult to relocate. Costs associated with infrastructure operation increase significantly when managers are forced — typically because of a lack of money — to be reactive rather than proactive when it comes to addressing problems.

Janine Burke-Wells, the executive director of the Warwick Sewer Authority, recently had to deal with the collapse of a concrete sewer line that unleashed an estimated 300,000 gallons of raw sewage into Buckeye Brook. It took four weeks and cost $350,000 to replace 700 feet of sewer line.

She noted that the replacement of 700 feet of sewer line for a recently planned project cost only $64,000.

The Warwick Sewer Authority is collecting and recording data regarding the condition of system sections, such as age, materials used, and risk of failure, as it creates an inventory in hopes of fixing problems before they become emergencies.

“We want a master plan in place instead of rushing from one emergency to another,” said Burke-Wells, the authority’s executive director for the past 10 years. “We’re creating a plan for how to fix our infrastructure before emergencies arise.”

DEM’s Patenaude said decisions about building new infrastructure, or adapting what exists now, must be strategic and often incremental. He also said designing with future conditions in mind will improve public safety and avoid costly repairs caused by increasingly harsher weather.

“How much more money do we spend to protect this infrastructure is a question that continuously needs to be answered,” Patenaude said. “There’s millions of dollars of equipment in these plants, but it might make sense to let the system flood and repair it for twenty million as opposed to building a fifty million dollar wall to protect it.

“This infrastructure is in constant need of repair, maintenance, and replacement, like a car. You need to understand what you own and how to keep it working.”

Climate stress

By their very nature, wastewater treatment plants are sited in flood-prone areas, to use gravity to help lessen pumping and electricity costs. But in Rhode Island, as elsewhere, more intense storms are damaging these low-lying plants and pump stations, according to a 2017 study.

The floods of March 2010 are a prime example of climate-related damage, and it wasn’t the Ocean State’s 400-mile coastline that felt the effects. The planet’s changing climate is impacting more than sea levels and Greenland’s melting ice sheet.

The flooding that occurred eight years ago wasn’t coastal, as might happen during the storm surge of a hurricane, but rather it was riverine, as heavy rains caused rivers to rise above their banks and flow across floodplains. This happened along several of Rhode Island’s major rivers, and many areas of the state experienced severe flooding twice: first on March 15, which broke previous flood records, and again March 30-31, an unprecedented weather event that exceeded the record set two weeks earlier.

After the floods, which severely damaged Warwick’s wastewater treatment plant — valued at $250 million — to a tune of $21 million, the sewer authority elevated the levee around its pump station 6 feet to withstand a 500-year flood event. The facility also had to reintroduce its waste-eating bacteria after the flood waters receded.

As part of broader state efforts to build climate resilience, last year’s study also includes recommendations to help mitigate the risk of flooding, storm surge, and other severe-weather impacts to Rhode Island’s wastewater treatment facilities. It’s expected that continued climate change will accelerate this risk, according to state officials.

Of the state’s 19 major treatment facilities, seven are predicted to become predominantly inundated in a catastrophic event, according to the $222,900 study.

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), in cooperation with the state’s Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) and municipalities, commissioned the study to help the state and local communities better understand the threats posed by climate change and take action to protect wastewater infrastructure.

Adaptive strategies recommended in the study include: hardening, such as building walls and dikes; relocating and/or elevating equipment and systems; standardizing equipment and/or stocking spare parts; redundancy, such as providing means to convey wastewater to two pump stations or using portable, temporary pumps; and wet-weather bypasses that control flow to surface waters to avoid flooding public ways.

Patenaude said about half of the report’s recommendations can be done for $50,000 or less. He noted that a $10,000 hatch installed at the Cranston wastewater treatment facility a year and half before the March 2010 floods prevented “millions of dollars in damage.”

Based on an analysis of recent storms and new and existing flood mapping, the 246-page study includes individual risk assessments for each plant, with a series of suggested improvements to help protect the facility from future flooding.

For example, the Bristol facility, at 2 Plant Ave., experiences localized flooding from Tanyard Brook to the north and west, and from adjacent wetlands to the south. This flooding, combined with limited plant capacity, leads to sewage overflows during wet weather, which have negative impacts on Bristol Harbor, Narragansett Bay, the Kickemuit River, and Mount Hope Bay.

Improvement recommendations include protecting the facility with flood barriers and elevating critical equipment, and elevating the pump station building above flood elevation or relocating the pump station inland.

In East Providence, extensive infiltration and inflow issues are being addressed in a number of ways, including raising manhole covers and epoxy lining collection system piping.

Some of Westerly’s pump stations are subject to inundation from both coastal and inland flooding. Recommendations include protecting facility’s entrances with flood barriers and elevating the backup generator systems.

“We are already confronting rising seas, warmer weather, and more intense rainstorms,” DEM director Janet Coit said when the report was released. “The vibrancy of our economy and health of our communities depend on us taking practical actions now to prepare for climate change. That means identifying and addressing areas where our infrastructure is at risk.”

Since the floods, Patenaude said DEM and wastewater treatment plant managers have begun working closely with the National Weather Service and staff are being trained to deal with climate-change impacts.

The three Ps

Wet-Naps, baby wipes, adult wipes, and other consumer hygiene products are often marketed as “flushable.” They aren’t. These products create blockages in residential and municipal sewer systems, as the pipes, pumps, and other equipment aren’t capable of handling wipes that remove makeup or treat hemorrhoids.

Burke-Wells said it’s easy to remember what can be flushed: “pee, poop, and paper (toilet only). That’s it.”

Several recent studies have provided evidence to suggest that wipes branded as “flushable” are clogging wastewater systems and getting caught up in pumps. These problems are costing U.S. utilities up to $1 billion annually, according to the National Association of Clean Water Agencies.

Since 2014, several communities have filed class action lawsuits against flushable wipe companies and retailers.

“This is somewhat of a new problem — flushable consumer products that aren’t,” said Patenaude, who has spent the past 30 years working in DEM’s Office of Water Resources as an inspector and supervisor. “These items aren’t degrading in the sewers. When we try to prohibit or regulate them, the industry fights back.”

Hygiene and cleaning wipes, however, aren’t the only obstructions that gum up wastewater infrastructure. During a recent ecoRI News tour of Warwick’s wastewater treatment plant, Burke-Wells listed off a number of other problem items that get flushed often: tampons, condoms, beepers, cell phones, sanitary napkins, rags, and toys.

The plant’s preliminary treatment system removes about 200 wet tons of debris annually. This debris, which also includes grit and other screened materials, is sent to the Central Landfill.

Keeping Rhode Island’s wastewater treatment plants running efficiently — a charge that is “part science and part art,” said Burke-Wells — is no easy task, especially when funding doesn’t necessarily keep pace with man-made pressures.