Site of Invenergy Power Plant Long Ago Deemed Fatally Flawed

Differences in siting of Ocean State Power and Clear River Energy Center show how much Rhode Island’s environmental concerns have waned

August 12, 2018

BURRILLVILLE, R.I. — The vast forest canopy of northwest Rhode Island, which boasts a rich ecosystem and is home to several public parks, was sheared nearly 30 years ago, but the gash could have been far worse had the Ocean State Power facility been sited where a Chicago-based energy developer now wants to build a new fossil-fuel power plant.

In the late 1980s the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) all agreed that the so-called Buck Hill Road site, about 6 miles southwest of where Ocean State Power now stands, wasn’t an environmentally responsible location for a fossil-fuel power plant.

Fast forward to present day, and all of that documented environmental work and agency concern didn’t stop Invenergy Thermal Development LLC and Rhode Island elected officials from embracing the construction of a nearly 1,000-megawatt power plant some 3,000 feet southeast of that alternative Ocean State Power site.

Ocean State Power, 1575 Sherman Farm Road in the village of Harrisville, began operating in 1990. The facility, about half the size of the proposed Clear River Energy Center, required FERC approval and an environmental impact statement was conducted. For reasons that remain unclear, the Clear River Energy Center doesn’t require FERC approval and no environmental impact statement has been done, leaving opponents frustrated and triggering court battles.

During the siting process for Ocean State Power, 82 locations throughout southern New England were reviewed. Only six sites for the Clear River Energy Center were considered, and most of that discussion focused solely on the controversial Buck Hill Road site.

In fact, two of the handful of Ocean State Power finalist sites, 1575 Sherman Farm Road and Buck Hill Road, were both deemed inappropriate by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

“Based on our review of the DEIS (Draft Environmental Impact Statement) and other relevant information, we recommend that the Buck Hill Road and Sherman Farm Road sites be deleted from further consideration as potential locations for the proposed combined-cycle power plant,” Gordon Beckett, New England supervisor for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, wrote in a letter attached to the July 1988 Ocean State Power Project Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume II Letters and Comments. “We believe the proposed project is inconsistent and incompatible with the existing land use on and adjacent to these Wildlife Management Areas.”

Beckett also wrote that, “We believe siting these facilities close to wildlife management areas, parks and similar public facilities should be considered fatal flaws and, therefore, the Buck Hill Road and Sherman Farm Road sites should be eliminated from further consideration.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) noted that the “Ironstone” site in Uxbridge, Mass., was better suited to host a power plant since it would be reusing an industrial site next to a state highway (Route 146) and would be conveniently distant from both human populations and wildlife habitats.

The EPA concluded that the DEIS “contains enough information for us to conclude from our review that the project could cause substantial water quality, wetlands and noise impacts, and that these impacts could be largely avoided through selection of the environmentally preferable site — Ironstone in Uxbridge,” according to the Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume II Letters and Comments.

The federal agencies’ concerns were ignored, and the 560-megawatt Ocean State Power facility was built on Sherman Farm Road, half a mile from the 1,548-acre Black Hut Management Area — the preferred site of the developer, the Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co.

Despite a lengthy paper trail condemning the Buck Hill Road site as a power-plant option, Invenergy’s preferred site a half mile away has been given the green light by state officials unmoved or unaware of past concerns.

In its updated advisory opinion, the Rhode Island Division of Statewide Planning says the natural-gas/diesel-fueled Clear River Energy Center will not impinge on state open space and greenway master plans, such as the Ocean State Outdoors or the Forest Resources Management Plan.

Statewide Planning also claims the proposed power plant doesn’t conflict with any aspects of the State Guide Plan. Its most recent opinion claims the site was never singled out in state plans for land protection.

DEM’s most recent advisory opinion avoids declaring whether the Clear River Energy Center should be approved or denied. The state agency’s waffling stems from a reluctance to determine if the facility will cause unacceptable harm to the environment. The Rhode Island Energy Facilities Siting Board (EFSB) had hoped to have DEM answer that concern, but the agency said its response is contingent on the outcome of pending permits: three pollution permits, one permit to destroy wetlands, and permits for stormwater and wastewater management. The EFSB doesn’t require that they be issued as part of the application vetting process.

If those permits are granted — something that likely wouldn’t happen until the EFSB renders a decision — DEM said, “It is a formal declaration that the proposed facility has met the standards and criteria for acceptable harm to the environment as established in state and federal laws and regulations.”

DEM’s most recent advisory opinion does maintain its original conclusion that the power plant will not impact Rhode Island’s compliance with the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

To meet the goals set in the 2016 Paris Agreement, agreed upon to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, “no new investment in fossil electricity infrastructure is feasible from 2017 at the latest,” University of Oxford academics concluded in a study published in 2016.

A recent report published by IOP suggests that in order to avoid a 2-degree Celsius global increase in temperature all existing proposed power plants must not be built.

“Even if all currently planned projects are immediately suspended, up to 20 percent of global fossil-fuel generation capacity would still have to be stranded (that is, prematurely decommissioned, underutilized, or subject to costly retrofitting) if humanity is to meet the climate goals set out in the Paris Agreement,” according to the May report.

Last June, Gov. Gina Raimondo signed an executive order “reaffirming Rhode Island’s commitment to the principles of the Paris Climate Agreement.” The toothless order notes that “Rhode Island is home to a wealth of historic parks, beaches, forestlands and some 150,000 acres of conservation lands that contribute to its natural beauty, strengthen its resilience, and promote quality of life, tourism and a stronger economy.”

Apparently, a stronger economy requires championing a climate-changing behemoth that could roar for decades be built among wildlife management areas and popular public recreation destinations. Past and present concerns about the environmental risks associated with developing the Buck Hill Road site have been drowned out by the constant cry of “jobs.”

Testimony by Anthony Zemba, a senior ecologist for Fitzgerald & Halliday Inc. and a sworn expert witness for the town of Burrillville in the Clear River Energy Center (CREC) application process, notes that “significant adverse impacts to wetlands will occur” if the power plant is built.

“It is possible that minimization measures might reduce the severity of some of the adverse wetland impacts on the site, but in the realm of environmental impact analysis, significance is determined by context and intensity,” he said. “In the case of the proposed CREC facility, there are two wetland resources identified on site as ‘Special Aquatic Sites.’ … One special aquatic site would be completely obliterated due to the construction of the facility. The other would lose the forest surrounding it, rendering the supportive habitat for obligate vernal pond species inhabiting that pool severely degraded.”

Environmental impact statement missing

The EFSB was created in 1986 by an act of the General Assembly. Ocean State Power’s application was filed with the EFSB in mid-January 1987.

At the behest of then-Gov. Edward DiPrete, and in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), FERC was eventually requested to conduct an environmental impact statement (EIS) for the Ocean State Power (OSP) project. No such request has been made by Raimondo or the current EFSB for the Clear River Energy Center.

In May, Michael Healey, DEM’s chief public affairs officer, told ecoRI News that, “DEM is not aware of any requirement for Invenergy/Clean River Energy to submit an EIS. More to the point, we’re not aware of any statute or regulation giving DEM the legal standing to require an EIS where no federal jurisdiction exists.”

About 25 miles to the south, on Providence’s South Side, where another fossil-fuel project is happening, state officials were again left powerless to do anything, this time because federal jurisdiction does exist. Rhode Island’s congressional delegation has remained silent on the project.

During the Ocean State Power application process state officials were far less apathetic to environmental concerns. They didn’t automatically elevate jobs, economic growth, and campaign promises above all else.

At a public hearing in April 1988, Sandy Sullivan, assistant director of the Rhode Island Office of Intergovernmental Relations, presented the governor’s position on the project, as noted on page M-3 in the Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume II Letters and Comments.

Sullivan testified that DiPrete supported the project, but with one stipulation: “To maintain Rhode Island’s present strong economic growth, adequate and reliable electricity supplies are critical. With this background, the Governor has supported the proposed OSP project, on the strong conditions that the plant be environmentally sound and that a thorough analysis be undertaken to ascertain the effects of the plant’s operation on the Towns of Burrillville and Uxbridge. The Governor requested that an EIS be conducted, and the state’s regulatory proceedings have been delayed to allow preparation of the EIS to follow the NEPA process.”

Rhode Island’s first EFSB — Mary Kilmarx, chairwoman of the Public Utilities Commission, Robert Bendick, DEM director, and Daniel Varin, associate director of administration for Statewide Planning — agreed with DiPrete that an EIS needed to be done, saying such a report “is essential to the Board’s deliberations.”

“While the Board does not have jurisdiction over major environmental permits, e.g. permits required under the Clean Air Act, state policy requires that a major energy facility ‘produce the fewest possible adverse effects on the quality of the state’s environment’ and the Board must implement that policy in its final decision,” according to Ocean State Power: Final Decision and Order. “Thus, we conclude that the Board has both the responsibility and the power to evaluate all individual and cumulative environmental impacts of the proposed facility before arriving at a final decision regarding the OSP application. Preparation of an EIS is the most efficient way of identifying those impacts for Board review.”

Late last year, seeing that state officials weren’t going to require that an environmental impact statement be done, the town of Burrillville requested one. The EFSB said it was too late in the process for such a report.

Nearly three decades ago, Ocean State Power defended its preferred site at Sherman Farm Road against both the EPA and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service by essentially arguing that the Black Hut Management Area wasn’t as environmentally significant as the George Washington-Pulaski forest and the Buck Hill Wildlife Management Area that surround the Buck Hill Road site.

To make that case, OSP’s director of environmental affairs, James O’Neill Collins, argued that the two protected areas were hardly of equal conservation and recreational value.

With three adjacent and significant conservation and recreational holdings, including the Boy Scout reservation, plus a record of greater biological significance in reference to rare and endangered species, Collins cited “sound reasons for excluding the Buck Hill Road site from consideration.”

Those “sound reasons” seem not to apply today, however. Little of the information gathered for the Ocean State Power EIS has been sourced for the CREC project. Even less of what has been learned about the forested area since the late ’80s is being considered as the EFSB deliberates the Invenergy project.

Sound of environmental silence is deafening

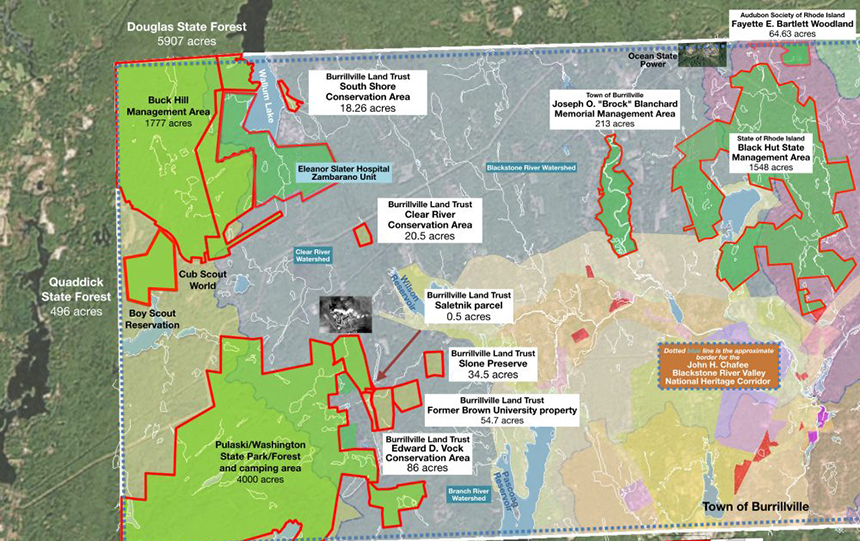

The Buck Hill Road site is one of seven contiguous parcels owned by the Algonquin Gas Transmission Co. with addresses on Wallum Lake and Buck Hill roads. The site for Invenergy’s proposed Clear River Energy Center, including its 0.8-mile power-line right-of-way that would connect the power plant to an existing National Grid power line, would be subdivided, in whole or in part, from five of those seven Algonquin parcels, including the Buck Hill Road site that was long ago deemed environmentally inappropriate for a power plant.

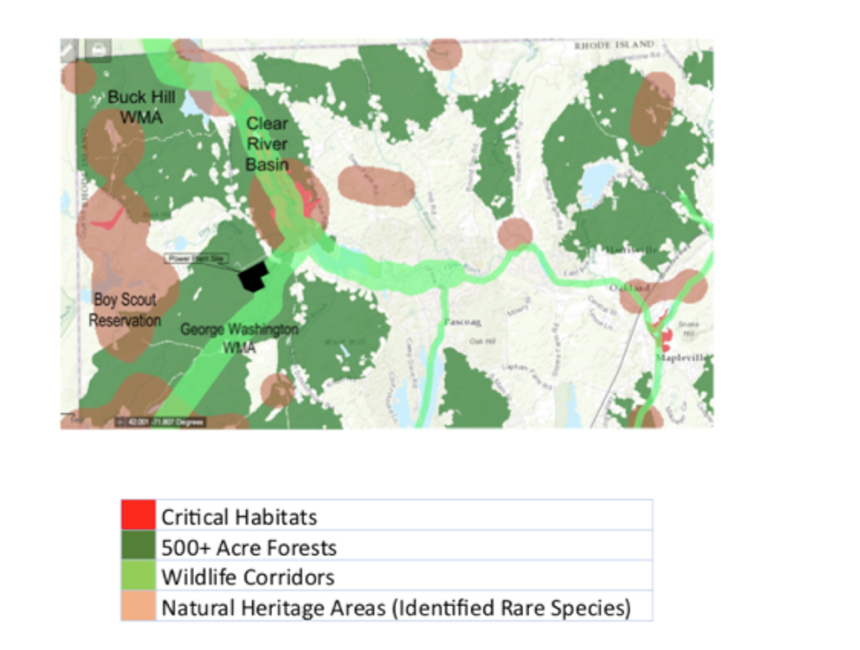

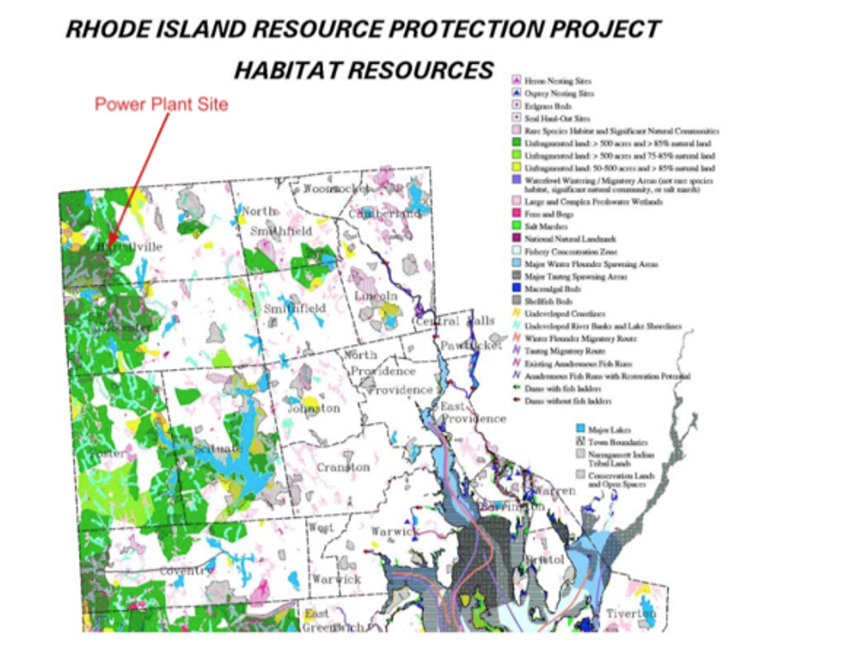

The Clear River Energy Center site is across the way from the Clear River basin and critical habitat areas; would be located some 200 feet from Iron Mine Brook, a Clear River tributary; a right-of-way would cross Dry Arm Brook wetlands, an ecologically sensitive white cedar swamp; would be near a Boy Scout reservation; and would be situated among 16,000 acres of protected wilderness in three states: George Washington Management Area/Pulaski State Park, Durfee Hill Management Area, and Buck Hill Management Area in Rhode Island; Quaddick State Park in Connecticut; and Douglas State Forest and Mine Brook Wildlife Management Area in Massachusetts.

Kevin Cleary, chairman of the Burrillville Conservation Commission, has noted that the proposed location of the Clear River Energy Center is “part of the only remaining intact contiguous forest along the entire Eastern Seaboard.”

The Nature Conservancy says the power plant would be built right on top of a critical pinch point in an important habitat corridor. This forest that spans three states features beaver dams and small ponds that connect to streams and rivers to form a watershed that acts as an important filter for Narragansett Bay.

In a May 25, 1988 letter addressing the siting of Ocean State Power, Christopher Raithel, a natural resources specialist for DEM, wrote that Dry Arm Brook “has been recommended as one of the finest examples of a White Cedar swamp” in Rhode Island.

An Invenergy-funded study found 47 species identified in the Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan as “species of greatest conservation need,” including some that are endangered or threatened, such as the bobcat and spotted turtle, on the site of the proposed fossil-fuel power plant.

The presence of state-listed species indicate Burrillville’s forestland is of high integrity and maturity. Of the 17 state-listed species — animal, insect and plant — found on the proposed site of the Clear River Energy Center, one is state endangered (cerulean warbler); two are protected (eastern box turtle and spotted turtle); four are state threatened (black-throated blue warbler, blackburnian warbler, northern parula and bobcat); and 10 are species of concern (great blue heron, Cooper’s hawk, pileated woodpecker, worm-eating warbler, white-throated sparrow, dark-eyed junco, arrowhead spiketail, wild calla, white-edge sedge and pointed trillium).

It’s been estimated that the Clear River Energy Center’s construction and operation would impact at least 200 acres of forestland. The heavily forested northwest corner of Rhode Island is home to hundreds of wildlife species, including the hairy woodpecker, the wood frog, red fox, gray fox, the six-spotted tiger beetle, and the wood turtle, which has become increasingly rare because of its complex habitat needs.

Forest fragmentation, an expanding concern in Rhode Island, invites invasive species, such as multiflora rose and Japanese barberry, to displace established vegetation and decrease the value of an ecosystem.

In 2010, DEM classified the region as a priority forest and wetland area.

According to the most recent Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan, fragmentation is linked to the impacts of climate change, because the dispersal and migration of forest plants and animals are disrupted.

A 2016 report by the Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council acknowledges the importance of preserving and expanding wetlands and forests in Rhode Island to help mitigate the impacts of climate change.

In its original advisory opinion for the proposed Clear River Energy Center, DEM concluded that, “The location of a [power plant] of this size and scope immediately adjacent to substantial acreage of state holdings of conservation land is not consistent with the conservation priorities that informed these state conservation lands.”

According to that advisory opinion, “Given the weight of this threat in an already fragmented landscape, the best course of action is to avoid further fragmentation to the greatest extent practicable.”

The fossil-fuel power plant proposed by Invenergy, though, has received a tiny fraction of the environmental concern that was so well documented in the Ocean State Power siting process.

In this era of climate-change awareness, one would think the environmental and greenhouse-gas impacts — locally, regionally, nationally, and globally — of a proposed fossil-fuel power plant would be closely scrutinized. But those concerns have failed to register with Rhode Island’s top elected officials.

When the Clear River Energy Center project was announced in 2015 no concerns about its environmental, public health, or climate impacts were noted. That lack of concern has persisted for three years. For all the flaws during the siting of Ocean State Power, such as not building the facility at a vacant gravel pit in nearby Uxbridge, environmental impacts were studied, discussed, and noted.

That hasn’t been the case with the Clear River Energy Center.

Gov. Raimondo enthusiastically endorsed the project when it was announced. During a press event three summers ago, Invenergy CEO Michael Polsky and Raimondo jointly announced the fossil-fuel project. The governor thanked the out-of-state energy developer for investing in Rhode Island.

“I know you have choices about where you could be and I’m pleased you’ve chosen Rhode Island, and you should know we are going to make sure that you are successful here,” Raimondo said.

The governor’s public support of the project has been less effusive during the past 18 months, as opposition to the facility has grown. Now when speaking about the project she once waved pom-poms for, Raimondo repeatedly says she wants to “let the process play out,” something she didn’t do when she spent nearly two years celebrating the facility’s construction and providing it with needed political momentum.

Speaker of the House Nicholas Mattiello has also been a project cheerleader. Neither elected official has publicly expressed concerns about the proposed power plant’s climate or environmental impacts.

The state Office of Energy Resources has endorsed the Clear River Energy Center, claiming it will lower carbon emissions and help Rhode Island meet its greenhouse gas-reduction goals.

Rhode Island’s congressional delegation has remained silent on the project.

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsRecent Comments

Leave a Reply

Related Stories

Your support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings

its discouraging that so much effort is needed to oppose this bad power plant proposal, effort that might have gone into reducing demand for energy or developing cleaner, better sited energy. Why can’t Invenergy face that this project is not wanted except by the few who wold profit from it and move on to something else?

It’s too bad or elected State leaders won’t step up and speak the truth. They’re all just scared to speak it. Painfully shameful our leaders don’t have the course to step up and do whyat right fire the people. Heads are all in the sand in the state level.

This plant is not needed.

I have been to the EFSB’s offices and have read the record of the EFSB’s Ocean State Power case from ’87-’88, including a document sent by RI DEM in July 1987 to Patty Marajh, of KRT, Concord Ma—Ocean State’s environmental consultants.

Anticipating that the proposed power plant would undergo an Environmental Impact Statement, KRT had presented to DEM for comment regarding environmental impact, 7 possible alternative Rhode Island sites, including the site then, as now, owned by the Algonquin Gas Transmission Company which is planned to become part of the Invenergy power project if it is approved. DEM biologist, Chris Raithel, of DEM’s threatened species and rare habitat watchdog, the Natural Heritage Program, (which was disbanded in 2007,) wrote commentary and included maps of each power plant site and any sensitive environmental sites nearby if these existed. This is what Raithel wrote about "site #1," the so called "Buck Hill Road site" which will host part of the Invenergy project:

"As can be seen on the accompanying maps, the entire northwest corner of Rhode Island is not only botanically significant, but is highly utilized for recreational purposes, including camping (George Washington and Buck Hill Scout Reservation), hunting, fishing and hiking, among others. I would recommend that site #1 [the Buck Hill Road site] not be considered for this power plant project, not only because of its potential impact to significant wildlife and plant species as well as to recreation in this area. On the basis of what I know of the seven sites you have listed, this seems by far the most inappropriate location for a power plant."

…No wonder there has been no sensible call from the Governor’s office—a la Governor DiPrete—for an Environmental Impact Statement for the Clear River Energy Center. No wonder her Director of DEM, Janet Coit, spoke for the EFSB in refusing last December the Town of Burrillville’s motion calling upon the EFSB to conduct an Environmental Impact statement. The fix has been in from the beginning. It is obvious from the material collected in the OSP EIS that an Environmental Impact Statement would imperil the Invenergy project. Invenergy certainly knew this the moment it concluded its interrogation of the Algonquin Gas Transmission Co officials it met with and learned every detail of the site’s history. Which leaves this following question: Was Gina Raimondo and/or her staff informed of the OSP EIS and its relation to the proposed Invenergy site when the company’s officials came calling? How exactly did Invenergy, with the help of local intermediaries, finesse this conundrum? How was the EFSB prevented from emulating their 1988 predecessors?

Perhaps we will learn that when the appeal of Invenergy’s approval is heard in Superior Court.

As election season approaches I would be interested to know who, if anyone, is a candidate that residents could support who is in opposition of the proposed plant.

You can’t keep destroying the natural filters for Narraganset Bay. If you do, it won’t be long before it smells like Florida.

Beth, so far I have read statements against he power plant, on various grounds, by Fung, Morgan, Flanders, Dickinson and Brown. Flanders’ was the most pointed, the others rather vague on details such as the exact location being next to a state forest, and none have referenced the big question that the Ocean State Power EFSB vetting raises: "Why no Environmental Impact Statement for Invenergy?"

This is precisely why Rhode Island needs to pass state law requiring environmental review for discretionary permits (ie, many environmental permits) similar to NEPA. See New York’s State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA), Massachusetts’ Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA), and California’s California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This ensures local natural resources conservation and management regardless of federal jurisdiction and provides assurances that local interests and needs are formally accepted and addressed during the entitlements process.