Environmental Racism Puts South Side’s Health at Risk

Another LNG facility is proposed for two Providence neighborhoods that have experienced long-ignored pollution problems and their related health impacts

February 9, 2018

PROVIDENCE — During a contentious public hearing last November, in the bowels of a state building, Rep. Marcia Ranglin-Vassell told those attending that, “Our community is not a dumping ground for rich corporations.”

Sadly, the South Side’s current and past history is plagued by rampant pollution. Her constituents’ zip code has been degraded by industrial toxins.

The Nov. 28 hearing, which was held in the basement of the Department of Administration building on Smith Street and featured a police presence, provided a delayed opportunity for opponents to express concerns about National Grid’s plan to build more polluting infrastructure along the Providence waterfront. The proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility would pose additional health threats to already-vulnerable South Side neighborhoods.

Ranglin-Vassell, D-Providence, called the project a “toxic facility” and an “environmental threat.” The District 5 representative and public-school teacher told the Coastal Resources Management Council board she strongly opposed the facility and is concerned about public health.

“This matter before you today will adversely effect my neighbors in an already-compromised neighborhood,” Ranglin-Vassell said. “As a community health educator … I know this is a form of environmental justice … environmental racism. By wanting to build in this neighborhood sets a clear message National Grid does not care about our infants, children, seniors … our poorest and most vulnerable citizens, many of whom are already suffering from compromised immune systems. … How much more can mostly poor immigrant families endure?”

Environmental racism is the disproportionate impact of environmental and public-health hazards on people of color and the poor. In 2015, the Rhode Island Department of Health created 10 Health Equity Zones, including one for the South Side, to: “Support innovative approaches to prevent chronic diseases, improve birth outcomes, and improve the social and environmental conditions of neighborhoods across the state.”

Hispanics and African-Americans comprise the majority of the South Side’s population. The median family income is about $23,300, compared with $32,000 for Providence as a whole. More than one out of three families lives in poverty.

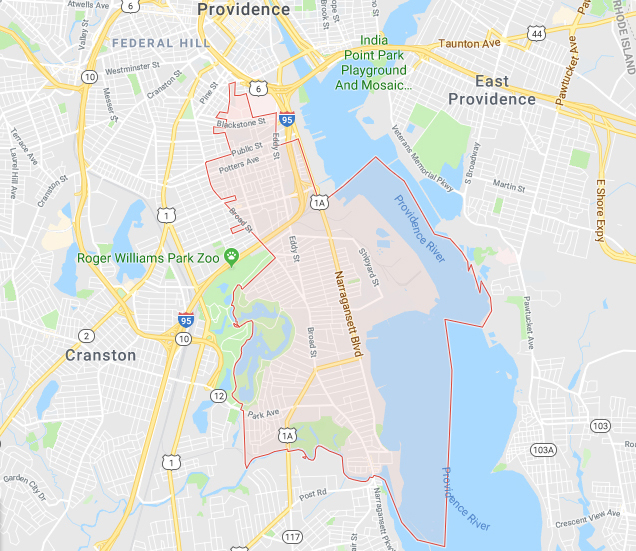

The low-income neighborhoods of South Providence and Washington Park, which are next to the city’s working waterfront, already suffer from high rates of asthma, presumably brought on by pollution from nearby Interstate 95 and industrial businesses at the Port of Providence.

In fact, a 2014 report by the Department of Health shows that the South Providence and Washington Park have some of the highest rates of asthma in the state. Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease that causes treatable episodes of coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, which can be life-threatening. Asthma attacks can be triggered by air pollutants.

Port of Providence companies include a liquid asphalt plant that emits compounds linked to child development disorders and to cancer, and an oil terminal that emits similar pollutants and other toxins linked to neurological and respiratory disorders.

The city’s industrial waterfront serves as a coal port, a fuel-oil depot, and a train depot for ethanol. It’s also home to several chemical-processing plants, including a Univar facility that manufactures chemicals for hydraulic fracturing (fracking). In 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) determined that the Univar plant accounted for 1,275 of the more than 4,000 pounds of chemicals Port of Providence industries spewed into the local environment that year.

The area proposed for National Grid’s second waterfront LNG facility is heavily contaminated. The 42-acre site on the Providence River has endured more than a century of pollution. It once hosted an Army rifle range, a coal gasification plant, and propane and kerosene storage facilities.

The activist group No LNG in PVD and area residents are concerned that construction at the site will spread the contaminants buried there by air and water. Two years ago the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) quietly approved a soil management permit for the site off Allens Avenue.

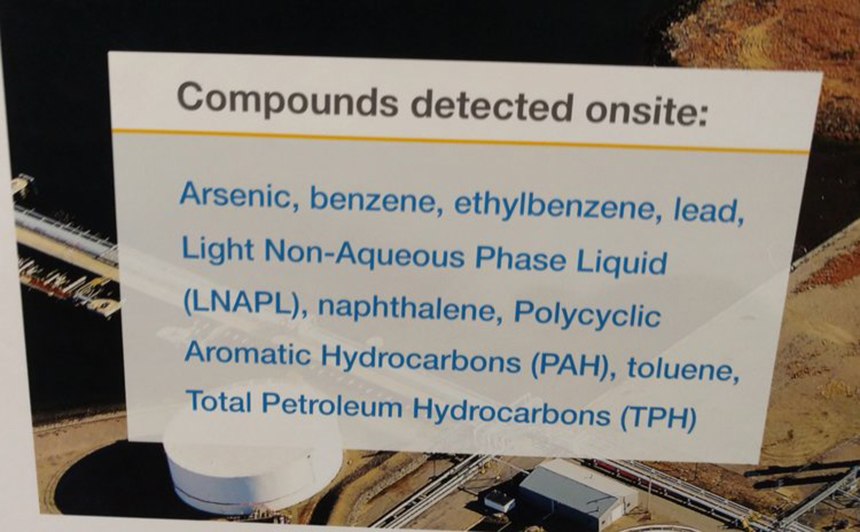

The dirt and groundwater were contaminated at the site between 1910 and 1945, as a result of operations by the Providence Gas Co. The site also has been used to process and store ammonia, toluene and liquefied natural gas.

Despite a partial cleanup of the area, the dirt contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which can cause increased incidences of lung, skin and bladder cancers; total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH), which can affect the central nervous system and can cause adverse effects on the blood, immune system, lungs, skin and eyes; volatile organic compounds, including benzene and formaldehyde that are listed as human carcinogens; and polychlorinated biphenyls, such as cyanide compounds, asbestos, lead and arsenic.

All 11 of the Providence polluters listed in the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory Program are within the city’s 02905 zip code. This section of the city contains a greater number of polluting facilities than any other zip code in Providence County. All 11 polluters are also within a mile radius of National Grid’s proposed LNG facility.

More than 60 people have submitted public comments to DEM in opposition to the National Grid fossil-fuel project.

Hurry-up offense

In 2015 National Grid submitted a proposal to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to develop the $100 million-plus facility to produce LNG directly from a natural-gas pipeline that delivers out-of-state fracked gas to Providence. LNG is produced by cooling natural gas to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, which reduces its volume by 600 times and puts it into liquid form. As described in its application, National Grid would then use tanker trucks to export the Providence-produced LNG, primarily to locations in Massachusetts.

The British-based multinational electricity and gas utility company sought fast-track approval for the project from FERC. The federal agency eventually decided a comprehensive environmental impact statement wasn’t warranted and only issued a limited assessment, which doesn’t require FERC to hold public hearings.

In September 2016, No LNG in PVD claimed that National Grid began excavation at the site without fulfilling a requirement for a public input plan, known as a PIP.

A company spokesman told ecoRI News at the time that the work being done at the contaminated site was unrelated to the LNG project and therefore didn’t require a PIP.

“It’s outrageous that there’s a known toxic site this close to my house, and we can go down Allens Avenue and see clouds of dust blowing off from the piles that National Grid is digging up,” No LNG in PVD member Monica Huertas said in late September 2016. “The whole point of this public involvement plan law is to address things like that, but National Grid is just ignoring our concerns and DEM isn’t doing anything to stop them.”

In fact, past and present state and local officials have done little to mitigate the area’s well-documented pollution problems. It could even be argued, rather easily, that they are equally complicit in creating the neighborhoods’ public-health threats.

The unresolved Rhode Island Recycled Metals case is a perfect example of the apathetic attitude officials hold for the health of South Providence and Washington Park.

Three governors, three mayors, two attorneys general, and two DEM directors have allowed the polluting scrap-metal business on the Providence waterfront to operate illegally since 2009. For nearly a decade the Allens Avenue business has contaminated the Providence River and upper Narragansett Bay with polluted runoff and fuel from derelict vessels the company has no authority to store.

The 6-acre property, a heavily polluted site taxpayers already helped clean up once, originally became contaminated between 1979 and 1989, when state officials failed to regulate the computer and electronics shredding facility operating there. The waterfront site has tested positive for toxins such as polychlorinated biphenyl, a carcinogen commonly used in electronics.

In addressing the most recent South Side public-health threat — the proposal for another LNG facility — it took state and local officials more than a year to give residents space to express their concerns about this fast-tracked fossil-fuel project. And when officials eventually got around to letting residents speak, the spaces provided and the confusing setup of some of the hearings — some were about the LNG project while others were about excavation work at the site; some were “listening” sessions while others were “comment” sessions — did little to assuage concerns that the entire process isn’t a bag job.

Few of the hearings have actually been held in the neighborhood where the project has been proposed. One information session was held at the Providence Public Safety Complex, the city’s main police and fire station. Some project opponents called the use of that location an “intimidation tactic.”

At the July 2017 police station hearing, Providence resident Kate Schapira spoke about the lack of community notification and information about the project, noting one person she just met only heard about the proposed LNG facility “this week.”

“This person lives in the neighborhood. She lives within the area affected by the project and she heard about it this week,” Schapira said. “So who else didn’t hear about it? Who else doesn’t know about it right now? Who else is in their house putting their kids to bed — they know they live in a dangerous area, everyone knows that. They know they live in an area that is making their kids sick. Everyone knows that, but people didn’t know about this project. People didn’t know about this project that was going to wake up this additional risk and this additional danger to their lives and their health was going forward next door. They didn’t know.”

Last month, at the project’s latest public meeting, opponents were welcomed into the Veterans Memorial Auditorium — much closer to the Statehouse and DEM headquarters than the asthma-suffering neighbors of South Providence and Washington Park — for a DEM listening session with a pat-down and bag search.

Aaron Jaehnig, chairman of the Rhode Island Sierra Club, recently sent a letter to the state attorney general noting his concerns about the Jan. 31 meeting at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium. He noted that both venue security and Providence Police officers prevented attendees from entering with laptops. Paper copies of books, notes and other materials were allowed.

“[T]he security measures were effectively discriminatory against people who use electronic means to have access to their materials: attendees whose testimony was stored on their laptops were unable to access it and thus unable to give it as planned. Electronic storage of research materials, notes, etc. is now commonly done on laptop computers and electronic pads rather than paper,” he wrote. “The restrictions were not included in the notice of the hearing. There was no reasonable way for the public to know that at a legal hearing, held at a large entertainment venue, that they would be denied admittance if they had their notes and materials in electronic form.”

Jaehnig also expressed concern with the meeting’s location, noting the hearing, with an increased level of security, was held in a location outside the neighborhood for which the LNG facility is proposed — “despite repeated requests to DEM that hearings for this project be held in the neighborhood in question.”

“I also witnessed people being forced to dispose of food and beverage even though the hearing was scheduled for three hours and venue concessions were not available, and if they were would have been cost prohibitive,” he wrote. “I was informed that it was standard security for the venue, but there was no expectation based on DEM’s notification or prior attendance at similar DEM hearings. Additionally, it was clearly witnessed that members of the press, DEM employees and National Grid employees were not subject to the same security measures.” (For the record, the ecoRI News reporter who covered the hearing was patted down and checked with a hand-held metal detector.)

The proposed LNG facility would release toxins such as ammonia, methanol and acetone into an already-stressed local environment. The natural-gas operation would have a 2.5-mile “hazard zone” from which residents would have to evacuate in the case of a malfunction. An explosion at a plant in Washington state four years ago that injured five workers and caused an evacuation of people within 2 miles of the facility demonstrates the risk associated with such facilities.

Some 80,000 residents and 300 schools are within the project’s hazard zone. A 2014 report by the Center for Effective Government ranked Rhode Island second in the nation for students attending schools near facilities that emit hazardous pollutants. The report also noted that the Providence waterfront has the highest concentration of polluting businesses in the state.

The aforementioned Univar plant, where more than 3 million pounds of toxic chemicals such as chlorine, ammonium and formaldehyde are stored, has a 14-mile hazard radius.

An LNG shipping terminal proposed for the same site on the city’s industrial waterfront was rejected by the federal government 13 years ago.

ecoRI News staffer Tim Faulkner contributed to this report.

Great piece Frank. My main observation regarding differential treatment of the press is that they were allowed to enter with laptops and other electronic devices and pads.