R.I. Environmental Enforcement Moves at Speed of Business

Since Smith Hill looks down on enforcement, state agencies tasked with protecting the Ocean State’s natural resources are labeled anti-business and their resources are gutted. The environment and public health pay the price.

December 10, 2018

In early November, one of Rhode Island’s TV news stations ran drone video shot from high above the forests of Foster. The imagery, with colors bursting, was stunning.

While environmental protections certainly helped make that amazing WPRI-TV video possible, they are constantly in the crosshairs here in Rhode Island, where the speediness of approving projects seems to take precedent over protections, where environmental enforcement is considered anti-business and/or confrontational. It isn’t and doesn’t have to be.

Protecting the state’s environment needs to be about more than promoting hunting grounds, fishing holes, beaches, and hiking trails and the license fees and tourism dollars these activities generate. Environmental protection is about more than conservation easements, hyping farmers markets, and holding an annual Great Outdoors Pursuit. It’s also about uniformed, timely, and fair enforcement.

Rhode Island’s 14 state beaches, seven major state parks, 40,000 acres of state forestland, and more than 400 miles of coastline are more than economic drivers. These areas, and the state’s dwindling collection of other open space, protect biodiversity, provide clean air and water, filter stormwater runoff, mitigate the impacts of climate change, and safeguard public health.

“There’s no value assigned to the resource itself, and the habitat, and the ecosystem,” said Save The Bay staff attorney Kendra Beaver, a Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) attorney for 10 years in the mid-1980s to mid-1990s. “It goes undervalued and is incrementally destroyed by a lack of enforcement.”

The state may be selling more hunting and fishing licenses and noticing more summer beach-goers, but the fact is Rhode Island’s much-ballyhooed natural resources are being eroded by fragmentation and stressed by human activity — it’s a global problem that, like here, isn’t being dealt with effectively because economic interests rule.

The laws — celebrated in the Rhode Island Statehouse when they are passed — to protect the state’s natural resources from encroaching development, sea-level rise, and pollution are quickly forgotten when it comes time to appease special interests.

For instance, DEM has never enforced the state law that requires businesses to recycle.

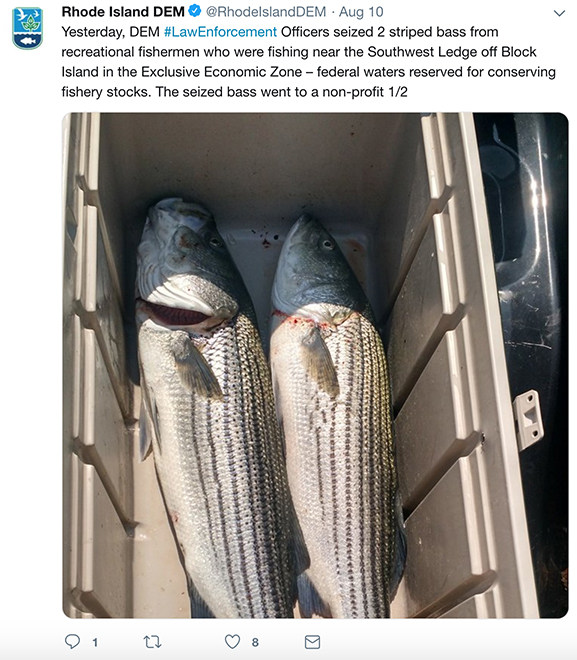

When it really matters, many of the state’s environmental regulations are enforced unhurriedly and/or selectively, depending if you are a 72-year-old Charlestown man charged with the possession of striped bass during the closed season, an industry with political pull, or a lawmaker with a business interest.

“You have this group of people in leadership in our state who oversee a budget who think enforcement is bad,” Beaver said.

Lack of resources

The continued slicing and dicing of enforcement resources and support makes it increasingly difficult for DEM and the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) to stay on top of violators, whether their actions are deliberate or accidental — even if major past polluters, like jewelry manufacturing, are history and more businesses, both large and small, are embracing the green movement.

To understand how the state prioritizes enforcement, DEM’s Office of Compliance & Inspection, which enforces more complex and egregious environmental violations than, say, arresting a guy for possessing illegally caught striped bass, actually has fewer full-time employees (24) than the agency’s Division of Law Enforcement (29 sworn officers, seven dispatchers, two clerical, and one marine maintenance staffer), which, among other things, busts individuals for catching too many premier game fish and important commercial species.

As of mid-October, DEM’s Office of Air Resources, which is responsible for the preservation, protection, and improvement of air quality in Rhode Island, had 25 full-time employees.

During an Oct. 17 Rhode Island Society of Environmental Professionals talk titled “Briefing by the Rhode Island DEM Section Chiefs” at DEM headquarters, Laurie Grandchamp, Office of Air Resources chief, noted that staffing has been a challenge.

“As I’ve said, I’ve been here in this position for a little more than a year but we’ve had quite a few retirements and quite a few vacancies,” she said. “In fact, in the two years that I’ve been with the office, we’ve probably had a turnover of about 30 percent. … That’s been challenging to making sure that we’re keeping up with the duties and responsibilities that we have.”

At that same presentation, Eric Beck, groundwater and wetland protection chief for DEM’s Office of Water Resources, noted that the “workload is up” and “resources are down.” This combination, he said, slows the permitting process.

“One thing I can’t commit to is placing a larger burden on my staff,” Beck said. “I can’t make the applicant’s life easier while accepting more work at the same time. You can see how that doesn’t work. It will break down.”

CRMC has an enforcement staff of two, to cover 420 miles of coastline being stressed by climate change and development. Its regulatory authority extends from 3 miles offshore to 200 feet inland from any coastal feature, including manmade structures. The agency has 28 full-time employees. CRMC doesn’t have full-time legal counsel. The agency uses an attorney part time for meetings and when needed, according to Laura Dwyer, CRMC’s public educator and information coordinator.

The council has spent the past five years asking for more enforcement staff and more enforcement capabilities. These annual budget requests are ignored by the Statehouse.

“The request from us for more enforcement capability means higher fines and more latitude to fine people in large quantities,” Dwyer said. “We do request it every year.”

Back in 2004, the General Assembly did approve an increase in CRMC’s maximum fine, from $1,000 to its current $2,500.

One of the many matters CRMC is responsible for is issuing permits for home building in coastal areas. The council, however, doesn’t have the staff to conduct inspections when a house is being constructed, to make sure the structure isn’t built closer to the shore than it should be, an existing natural buffer isn’t being destroyed, or an unapproved outbuilding isn’t being added.

Laura Miguel, who along with Brian Harrington are CRMC’s only enforcement staff, has been employed by the council since 1992. She can’t recall a single time when a compliance check was done after a permit was issued, unless a complaint was filed. She said the agency doesn’t have the staff to conduct such follow-up.

“They’re not going to know until way later … if someone reports it, because they don’t have sufficient staff to patrol their permits, to do compliance checks, let alone just patrol the coastline,” Beaver said. “Now you have a house and you gotta get it moved.”

For those who think a house can’t be built in Little Rhody where it shouldn’t, take a look at the 2014 Rhode Island Supreme Court case Rose Nulman Park Foundation v. Four Twenty Corp. A Rhode Island developer was ordered to remove a $1.8 million house built in 2009 on public parkland in Narragansett.

The three-story waterfront house in Point Judith — complete with a rooftop cabana with spa tub and wet bar — was built on land that belonged to the Rose Nulman Park Foundation.

CRMC deals with two types of violations: unpermitted actions and actions in violation of a permit. The most common violations are the removal, or failure to establish, vegetative buffers and the filling in of wetlands.

For Miguel, however, the most important issue she deals with is public access.

“For me personally, that’s a very critical role that we have: protecting access either at designated rights of way or when access has been required in a permit,” she said. “To me, that is a very important aspect of my job.”

Miguel and Harrington typically handle between 150 and 200 formal complaints a year, with about 100 going from complaint, through the enforcement process, to resolution. The duo addresses everything regarding enforcement, from minor infractions — an homeowner who unintentionally mowed down a natural buffer — to major violations, such as significant land development or impeding public access.

“There are folks who have figured out a way to circumvent our program and use the enforcement system to their benefit, or manipulate both,” Dwyer said. “It certainly happens.”

Miguel is considering asking for a drone in the fiscal 2020 CRMC budget, to improve the agency’s enforcement abilities.

Time-consuming work

The work required of DEM’s strained Office of Compliance & Inspection and CRMC’s skeleton enforcement staff includes inspections, title searches, investigating complaints, visiting aquaculture operations, filing and pursuing cases at hearings and in court, making sure public access to the ocean isn’t being choked off, monitoring consent agreements, testifying at hearings, and writing notices of violation and warning letters.

For example, correctly labeled drums and properly stored waste at a warehouse or chemical manufacturer matter, especially when, say, firefighters respond to an emergency. Unlabeled barrels and improperly stored waste and chemicals can lead to more than a polluted stream.

But protecting game-fish habitat, the coastal wetlands that buffer the state from rising waters, and emergency responders from corner-cutting businesses seem secondary, at least when it comes to how the state prioritizes its enforcement resources — resources the Statehouse consistently undermines during budget season by routinely underfunding the two agencies largely responsible for protecting the Ocean State’s environment: DEM and CRMC.

The number of full-time DEM employees was capped at 395 for fiscal 2019. As of Nov. 10, the agency was nearly two dozen short of that limit (374). More than a decade ago, the agency had 650 employees.

Beaver said DEM needs staff and not just inspectors. “They need lawyers to go to court, to look at land evidence records,” she said. “You need more than one witness to go to court and testify in these things. You have to staff up in order to have a good, strong enforcement program.”

DEM has five attorneys: one executive counsel, one deputy chief legal counsel, and three staff attorneys.

While Terrence Gray, DEM’s associate director for environmental protection, acknowledged the number of employees in the Office of Compliance & Inspection has decreased over the years, he said any agency or department would want additional resources.

“When you ask somebody can you use more resources … the answer is always yes,” said Gray, a 32-year DEM veteran. “But … we have to operate within the constraints that are out there, in terms of the budget, the system, and everything like that, so we spend a lot of time prioritizing issues. And the key thing is to take the most serious cases first.”

Gray said DEM submits proposals in the annual budget requesting additional resources, such as more inspectors. He noted that the agency’s repeated requests haven’t made it through the entire budget process.

“We’ve talked about this. We’ve had the opportunity to … say how important enforcement is,” he said. “And we’ve tried to get some support around further investment.”

Despite the wide-reaching importance of properly protecting the state’s natural resources, funding for environmental enforcement hasn’t been a Statehouse priority for the past few decades. That fact hasn’t changed under the Statehouse’s current leadership.

While DEM and CRMC enforcement staff is squeezed, Gov. Gina Raimondo’s Rhode Island Commerce Corporation staff grows and new positions are created and filled at the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) and the Department of Administration. Those agencies, for the most part, also offer better pay for comparable jobs.

Unfair competitive advantage

Rhode Island’s environmental enforcement moves at the speed of business — the governor’s Lean Government Initiative demands it. This rush to appease business interests has eroded the resources needed to conduct effective enforcement. This erosion began in the 1990s. It shows no signs of slowing.

ecoRI News spoke with Beaver and Save The Bay’s baykeeper, Michael Jarbeau, in early November at the organization’s Providence headquarters on Narragansett Bay. The environmental advocacy nonprofit began harping on the state’s lack of effective environmental enforcement a few years ago.

Beaver said she doesn’t think DEM’s enforcement approach has necessarily changed since she left the agency two-plus decades ago. She noted that DEM “definitely issues more warning letters” now, it works with companies more to get them into compliance, and there’s more agency outreach. All good practices, she said.

“The problem is to me not a difference in approach. It’s not following up, not having the staff,” Beaver said. “So you issue a warning letter; if you follow it up in a year with another warning letter, that’s not helpful. You need to have the staff in order to follow through. If you issue a warning letter that says come into compliance in 30 days, you need staff to go back in 30 days to see if they are in compliance. If they’re not, then you have to start taking harder action.”

Conservation organizations have noted that an inability to effectively enforce environmental law provides an economic incentive for less reputable businesses to skirt regulations, thereby giving them an unfair competitive advantage.

During a press conference in January 2016 at the Statehouse, David Caldwell Jr., of the Rhode Island Builders Association, said as much, noting that weak regulation enforcement hurts the environment and the businesses playing by the rules.

While he added that he would like to see improved efficiencies within DEM and CRMC to speed up the processing of applications and permits, he also said:

“There’s stacks of paper waiting to be approved while some businesses are polluting the bay. I’d like to see a healthy economy and a better environment. The better we dedicate resources to enforcement, the better we are for it and the better the economy will grow.”

Rhode Island’s top elected officials and appointed bureaucrats, however, only hear Caldwell’s plea for improved efficiencies. Businesses that, say, invest significant resources in installing stormwater management systems to mitigate the impacts of runoff watch the slow enforcement response to other businesses, or even a state agency, that illegally discharge polluted runoff into local waters.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), for instance, had to take RIDOT to court because DEM failed to adequately enforce the Clean Water Act and the terms and conditions of RIDOT’s national pollutant discharge elimination system permit.

Significant portions of the areas of Rhode Island polluted by RIDOT’s negligence and DEM’s casual enforcement were environmental justice areas, according to the settlement agreement.

Here are a few more examples of slow-moving DEM enforcement:

Constancia and F.C.C. Inc.: Freshwater Wetland File No. FW C11-0188 (Bristol)

The initial permit was approved in 2007, and was revised in February 2009. A Dec. 6, 2011 inspection revealed: clearing within swamp resulted in the unauthorized alteration of 3,040 square feet of freshwater wetland; clearing and filling, in the form of sediment, altered 14,560 square feet of freshwater wetland; no temporary erosion and sediment controls were installed; house was built in a location that differed from the location shown on the approved plan.

On Feb. 29, 2012 a notice of violation (NOV) was issued. No appeal was filed. The NOV could have been enforced in court on March 2012. On Jan. 28, 2014 the property was acquired by Global Consulting Group LLC through a mortgage foreclosure. The NOV wasn’t resolved until April 2016 — four years after it was issued and six years after the permit was issued and violations likely committed. The new owner restored the freshwater wetlands as required in the NOV and paid an administrative penalty of $5,000; no penalty for the violators, as DEM officials said the couple had “no ability to pay the remaining penalty.”

Ayn Wardo Realty LLC: Freshwater Wetland File No. C09-37 (Cumberland)

Inspections in April and August 2009 revealed clearing and filling — in the form of gravel, sand, rock, tree slash, logs, brick, and concrete — within the 100-year floodplain and 200-foot riverbank wetland of the Blackstone River, as 40,000 square feet were altered.

On July 22, 2010 a notice of intent to enforce was issued. An Aug. 27, 2010 inspection documented additional clearing, filling, and fill pushed into the Blackstone River. A Sept. 16, 2010 inspection found additional earthwork in the riverbank wetland and floodplain since the prior inspection on Aug. 27.

On March 28, 2011 an NOV was issued. An appeal was filed, but the defendant failed to appear for the hearing. The appeal was dismissed in August 2013. The original owner filed for bankruptcy and the property was acquired by a new owner. In May 2016, the new owner complied with the NOV and paid a penalty of $2,000.

OBF LLC: OWTS File No. CI09-137 (three-bedroom house in Little Compton)

A Nov. 18, 2009 inspection revealed that the property’s onsite wastewater treatment system (OWTS) failed and sewage was discharged. On June 25, 2010 an NOV was issued. No appeal was filed. The NOV could have been enforced court in July 2010.

DEM said the owner claimed that he never received the NOV. Since the original file couldn’t be found, there was no way to verify whether the NOV was properly served, so the penalty was waived.

The owner eventually repaired the septic system and was issued a certificate of conformance by DEM on Jan. 27, 2016.

Eli Metals Group: Air File No. 08-04 (Providence facility)

Eli Metals operated an organic solvent vapor cleaning machine — a batch vapor degreaser — using trichloroethylene (TCE) at its 91 Hartford Ave. facility. TCE is a hazardous air pollutant, a volatile organic compound, and is a toxic chemical regulated by federal and state air pollution control (APC) regulations.

An Aug. 11, 2005 inspection revealed noncompliance with APC regulations for failure to report usage of volatile organic compounds for the years 1999, 2003, and 2004. A Nov. 29, 2005 inspection showed continued noncompliance and also found multiple violations of an APC regulation pertaining to equipment, monitoring, record keeping, and reporting requirements for the degreaser.

On June 23, 2008 a NOV was issued for violating APC regulations for failure to control emissions from organic solvent cleaning and failure to keep records. An administrative penalty of $18,000 was imposed. No appeal was filed and NOV was ignored. The NOV could have been enforced in court in July 2008.

In March 2014, a consent agreement was reached. The business agreed to discontinue further use of the degreaser, render it inoperable, remove any waste contained in it, and properly dispose of that waste in accordance with DEM regulations. The defendant also agreed to pay an administrative penalty of $3,684 in 17 equal monthly installments.

DEM closed the file as “uncollectible debt” when a hired collection agency couldn’t proceed with the collection “because of the debtor’s age.”

Town of Johnston: Water Pollution File Nos. 14-29 and 10-092

On Dec. 19, 2003 a Rhode Island pollutant discharge elimination system (RIPDES) permit — “the backbone of the state’s water pollution control strategy,” according to DEM — was issued.

On March 18, 2004 the town of Johnston submitted a stormwater pollution prevention plan (SWPPP) for general permit coverage. On Oct. 31, 2005 the town obtained coverage under a general municipal separate storm sewer systems (MS4) permit. Such a permit requires: a revised SWPPP and scope of work to DEM’s Office of Water Resources (OWR) to implement stormwater controls in response to total maximum daily load (TMDL) determinations within 180 days of notification; submit annual reports to OWR; implement a public education program; issue public notices and provide an opportunity for public comment; implement an illicit discharge detection program; implement a construction site stormwater runoff control program; implement a post construction stormwater management program for new development and redevelopment projects; and implement a pollution prevention program for municipal operations.

On Jan. 31, 2007 the OWR invited all MS4s to participate in a voluntary education outreach program, but the town chose not to participate. On Aug. 29, 2007 OWR advised the town that a TMDL water-quality restoration plan was completed for the Woonasquatucket River and that stormwater from Johnston’s MS4 was contributing to bacteria and dissolved metals impairments in the river. The town failed to submit an amended SWPPP in response to the TMDL determination.

In 2009, the OWR reviewed the status of compliance for each MS4 in the state. The Johnston review revealed the following failures: implementation of a public education program; public notice of the annual reports for 2006, 2007, and 2008; implementation of an illicit discharge detection program; implementation of a construction site stormwater runoff program; implementation of a post-construction stormwater management program; and implementation of a pollution prevention program for municipal operations.

On Jan. 26 and April 24, 2009 and April 9, 2010 notices of intent to enforce were issued. The town failed to respond or comply. On Nov. 22, 2010 an NOV was issued for violating RIPDES regulations and an administrative penalty of $25,000 was assessed. An appeal was filed.

On March 24, 2014 a consent agreement was reached. The town agreed to undertake a number of actions, ranging in deadlines from April 31, 2014 to July 1, 2019. DEM waived the administrative penalty. The consent agreement is still open.

Mark J. Ginalski of East Providence: Sunken crane and barge

In fall 2017, a floating crane owned by an East Providence man sank in the Providence River. The crane is sticking out of the water and the rest of the vessel is submerged. A houseboat that was once attached to the barge is sunk elsewhere in upper Narragansett Bay.

DEM responded to a call in October 2017 that the barge was leaking oil. The owner was cited for violating five pollution laws and given 30 days to remove the barge and crane. The order was ignored.

In a July 31 letter to the owner, DEM threatened to impose a $25,000 daily fine. The agency followed its July 31 threat with several stern letters. On Aug. 31, DEM issued a notice of intent letter to enforce the July 31 letter. The owner eventually told the agency he couldn’t afford to move the vessel.

A Nov. 21 dive by ecoRI News contributor and professional diver Michael Lombardi found propane and/or natural-gas tanks, a welding unit, and a gas pump with a Honda engine among the items on the sunken barge. (Video at top of story.)

Untimely enforcement expensive

Failures like those listed above to enforce environmental law in a timely manner come at a price, according to Save The Bay.

Cause significant environmental degradation. Impacts from wetland alterations that destroy habitat are increased, pollutants are discharged into recreational waters, and people breathe in unpermitted emissions. “Each day of delay causes additional impacts to the resources and those impacts can’t be remedied.”

Complicate enforcement, because an inspection is required each time an action is taken; property may be transferred in the meantime, which causes additional legal work; and violators often escape the consequences.

Result in settlements that don’t fully protect the impacted resource.

Impact the strength of a case — i.e., how important is it if the agency waited years to enforce?

Fail to serve as a deterrent and creates an uneven playing field for compliant businesses.

“There is a lot of incremental degradation that’s going on by not being efficient and not having the staff to follow up on these violations,” Beaver said.

ecoRI News spoke with Gray and David Chopy, Office of Compliance & Inspection chief, Nov. 16 at DEM headquarters, 235 Promenade St. in Providence, about agency resources and environmental protections.

To offset staff reductions, they said DEM relies on efficiencies, priorities, and technology — Chopy, for example, mentioned that Google Earth has helped make enforcement easier. Gray noted that Rhode Island’s “business sector is a lot cleaner” and many companies today have a “better environmental ethic.”

Gray said the agency has “invested a lot in the computer system that supports Dave’s office.” He noted the agency’s “expedited citation process,” which was created about a decade ago and encourages the early settlement of straightforward violations with reduced penalties for noncompliance. He said expedited citations save DEM time and get things back into compliance quickly.

Chopy, a 33-year DEM employee, noted that the number of complaints the agency receives has “dropped quite significantly from where they were 10 to 15 years ago.”

“I think it’s because the environment overall is getting cleaner. The type of industries we have here are not what we used to have, so there’s just not as many things for people to complain about,” he said.

He added that if elected officials were getting calls about environmental concerns, that would get their attention.

“If they’re not getting those calls, they’re working on other things that they’re getting calls on,” Chopy said. “Plus, I think people generally use their senses to decide whether things are getting better or getting worse. If the water looks clean and the air is clean looking and it smells fine and they don’t see piles of waste everywhere, they’re going to think that things are generally better. And I think things are generally better.”

Looks, however, can be deceiving. Invisible contamination surrounds us. Particulate matter swirling in the winds around Westerly quarries and among the neighborhoods in South Providence isn’t necessarily noticeable. Lawn chemicals washing into nearby waters is hard to watch. Microfibers and microplastics are accumulating in the environment. A group of hazardous chemical compounds that are common in industrial processes and personal-care products but which aren’t typically monitored by the EPA have been detected throughout the Narragansett Bay watershed.

The good news, according to University of Rhode Island professor Rainer Lohmann, is that since the compounds weren’t detected in several samples, then “clearly you can get to almost zero. It means that Rhode Island has a number of point sources that potentially could be targeted for reduction. If DEM wanted to, they could probably identify where those compounds are coming from and maybe try to reduce their emissions. That would be a good thing for the bay.”

An economic bubble

Time and again, the governor’s office, the General Assembly, and DEM leadership stress the importance of being “business friendly.” They wrap statements about Rhode Island’s natural resources in an economic bubble, as if protecting the environment matters because it supports the economy and creates jobs. This messaging is relentless.

An Oct. 19 DEM press release seeking public feedback on outdoor recreation states that the inaugural report from the governor’s Outdoor Recreation Council “highlights the importance of the state’s recreational network to Rhode Island’s economic and cultural vitality.” It notes that, “According to the Outdoor Industry Association, outdoor recreation in Rhode Island generates $2.4 billion in consumer spending and supports 24,000 jobs each year.”

An Oct. 12 DEM press release announcing the opening of small-game hunting season notes that, “Hunters and anglers purchase around 70,000 licenses, permits, stamps, and tags each year and contribute more than $235 million to Rhode Island’s economy.”

An Oct. 3 DEM press release about improvements to the boat ramp at Glocester’s Echo Lake states that, “Recreational boating and fishing are ingrained in the culture of the Ocean State and are important economic drivers.” It notes that, “According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, there are approximately 175,000 recreational anglers (age 16+) in Rhode Island, and recreational fishing contributes more than $130 million to the economy each year.”

A Sept. 4 DEM press release inviting youth to a free waterfowl training workshop and mentored hunt repeats the “70,000 licenses and $235 million line.”

A Nov. 2, 2017 DEM press release touting the opening of muzzleloader deer hunting notes that “hunting plays an important role in connecting people with nature, supporting quality of life and family traditions, and attracting tourism.” It mentions that “hunting contributes more than $18 million annually to Rhode Island’s economy.”

A Dec. 8, 2016 DEM press release about stocking local waters with trout for the winter fishing season mentions that there are “approximately 175,000 recreational anglers (age 16+) in Rhode Island. And recreational fishing contributes more than $130 million to the economy each year.”

At a Statehouse hearing in May 2015 critics of DEM’s enforcement efficiency said the agency was getting better at issuing permits but was getting worse at stopping polluters.

“The enforcement capacity at the agency has been whittled away for 10 years now,” Save The Bay executive director Jonathan Stone said at that hearing.

To prove his point, Stone said that since 2005 DEM had cut its legal staff from nine attorneys to six; compliance and inspection officers had been reduced from 35 to 22; and OWR, which oversees water quality and wetlands, had dropped from 68 to 51 employees.

DEM director Janet Coit defended her agency by praising it for its business-friendly improvements, such as faster permitting and a new customer-service center.

“The governor is very focused on keeping jobs in Rhode Island, growing jobs, and promoting jobs,” Coit said at the hearing. “And I want to emphasize how much the infrastructure and parks and facilities of DEM are part of our tourism sector as well as a growing agriculture sector.”

She also noted that during the past 10 years, the agency had reduced the number of attorneys from eight to six, compliance and inspection personnel from 39 to 23, and water resources staff from 86 to 69.

Either way, everyone agreed that the number of DEM staff responsible for environmental enforcement had decreased. Those numbers haven’t improved much in the three years since.

Public shaming

During an interview with ecoRI News in late 2015, Coit, DEM director since 2011, said, “It can’t be about big business versus the environment. That can’t be the dichotomy. Both are extremely important. Our parks, beaches, bike paths, and forestry are part of the tourism economy, but they also contribute to quality of community and their health.”

Ample evidence, however, suggests the playing field tilts toward the bottom line. Rhode Island government conceals, impedes and/or minimizes more complex environmental enforcement issues and actions and makes a show out of busting the proverbial low-hanging fruit.

In 2012, when local fishermen and some General Assembly members were expressing concerns about large out-of-state trawlers fishing close to the Narragansett and Charlestown coastline, DEM wasn’t worried about overfishing, but did express concern about the economic impact of fishing revenue moving out of state.

When it comes to individual fisherman, however, overfishing is a priority. In late October, DEM’s Division of Law Enforcement arrested an East Greenwich man for taking 21 tautog.

In the detailed press release announcing the man’s arrest, Coit says, “Rhode Island’s natural resources such as saltwater fisheries are a public trust.”

DEM shames individual fishermen who have caught too many tautog and striped bass by e-mailing press releases and posting the enforcement action on social media, but buries formal enforcement actions against polluting businesses and homeowners with failing septic systems on a hard-to-find webpage. Chopy admitted that the agency’s monthly formal enforcement action summaries aren’t easy to find. He said DEM is working to make that information more visible.

No press release was issued in September when a Smithfield business was issued an NOV for violating hazardous waste regulations. No tweet three months ago shaming a Glocester couple for having a failed septic system that illegally discharged wastewater. No Facebook post in June when a Cranston business was issued an NOV for failing to determine if the waste generated onsite meets the definition of a hazardous waste, for not providing training to employees who handle and/or manage hazardous waste, and for mixing incompatible waste in a container in a manner that starts a fire.

Meanwhile, as the state protects the public trust from a poaching fisherman in Wickford Cove, two South Providence neighborhoods in an environmental justice zone have spent the past decade wondering why a waterfront metals recycler continues to be allowed to contaminate the Providence River with polluted runoff and fuel from derelict vessels the company has no business storing. The company opened in 2009 without many of the required permits, including the one needed to conduct car-crushing operations.

The fishermen’s offenses are considered “criminal” and the others, including the decade-long contamination of upper Narragansett Bay, are considered “administrative.” Catching too many of the wrong fish is a crime — unless you’re doing it with a big net stretched between trawlers and throwing the dead bycatch back — but a business that is caught dismantling, in the Providence River, vessels it doesn’t have the authority to be storing is a violation.

CRMC doesn’t publicize its enforcement actions online, something conservation groups believe the agency should.

Environmental organizations claim that staff cuts, early-retirement buyouts, and resource squeezing have lead to a decline in timely enforcement and follow-through — even while responsibilities have expanded because of new mandates, such as the Fresh Water Wetlands Act of 2014.

For the past few decades the Statehouse’s corner offices have methodically transformed the agency into a contracted developer for applicants, working with builders to push projects to the threshold of what is allowable. If that fails to satisfy chambers of commerce, industry trade groups, and other business interests, laws are passed and regulations rewritten.

However, adequate staff and resources and timely enforcement would, besides better protect the Ocean State’s lauded natural resources, also support the economy and create jobs, in construction — to build stormwater systems, for example — design consulting, engineering, and planning, and increase the need for workers who support those industries.

Editor’s note: This is the first story in a three-part series.

ecoRI News staffer Tim Faulkner contributed to this report.

I have written regularly about the stupidity of a real estate driven economic development model and how it is a disaster for the planet and the peop;le of Rhode Island. Real estate intersts dominate our political system, much to our detriment. Governor Wall St has continued the tradition of letting the rich rule. I offer up a short snippet of an essay I wrote on some of my adventures in permitting and trying to get a permit to do a restooration of amphibian habitat. The process is truly broken and Smith Hill, run by crimimals in the real estate industry, will nevr fix it.

"the entire model of real estate development driven economic development is broken. Broken so badly it ought to be abandoned. Economic development experts such as the IMF and the World Bank have repeatedly pointed out that subsidizing the rich to build buildings does not contribute to long term community prosperity and drives much of the inequality that is harming our communities. In Providence we make this worse by focusing on building subsidized buildings for the medical industrial complex, which guarantees that health care will be unaffordable for more and more people.

Some day we shall learn, but as long as Wall St and real estate interests determine our policies, be prepared for more hard times, especially when the next real estate bubble bursts. "

Thank you so much for your efforts. Tried to come up with something positive to say but it’s pretty discouraging all around, except for the efforts by people like you. I think many feel powerless. My own ideals were systematically beaten down during my career as a social worker in long term health care for 35 years. Dismissed as a ‘bleeding heart’ by both the corporation I worked for and the government agencies that supposedly monitored the industry. The only concern being the bottom line…a value the oversite agency ultimately respected and supported.

Thank you Tim for this detailed and informational report.

We should all contact the State of RI (Governor, DEM Director, and our State Senators/Reps to demand more cleanup and enforcement of environmental issues facing RI.