Rhode Island’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams

Department of Transportation's plans for 6-10 Connector contradict advice from experts invited to speak at a recent public meeting. State agency intends to maintain connector as highway.

March 26, 2016

PROVIDENCE — There was a difference of opinion at a recent public meeting about the reconstruction of the dilapidated 6-10 Connector. Three national experts with highway-removal experience recommended prioritizing pedestrian mobility and local car trips. Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) director Peter Alviti expressed a commitment to accommodating local and regional trips on more equal footing.

No one disagrees that the 6-10 Connector needs attention. Seven of nine bridges along the route are classified as structurally deficient. More than a decade ago, many of those bridges were reinforced with wooden buttresses. Now, ironically, the braces themselves have fallen into disrepair and need replacement, according to Alviti.

For decades, RIDOT has struggled internally over how to proceed with the 6-10 Connector. Alviti noted that after 30 years of design work, the plans to reconstruct the connector were only 30 percent complete when he was appointed as director last year. Furthermore, the plans called for a nearly identical reconstruction of the highway, despite the poor performance of the existing design, and the steep cost such a plan would entail.

“Historically, the way (RIDOT) has reacted is to rebuild what was (already) there — taking the worst conditioned roadways and bridges and rebuilding them over and over and over again. This led to the state having one of the worst transit systems and worst bridge and roadway systems in the country,” Alviti said during his presentation at the March 23 event. “We’ve set out to break that cycle.”

A different vision

The conversation surrounding the 6-10 Connector changed dramatically in 2014, after James Kennedy, author of the blog Transport Providence, proposed a completely different configuration for the highway. Kennedy recommended replacing the highway with a boulevard that would accommodate cars, pedestrians, cyclists and transit users.

Kennedy claimed traffic flow through the corridor would counterintuitively improve if the highway was drastically reduced in size and scope. He cited similar projects along the Embarcadero in San Francisco, the West Side Drive in New York City, and the Park East Freeway in Milwaukee.

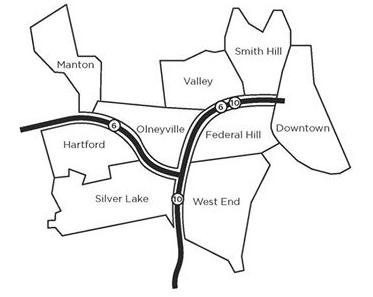

A boulevard would also benefit neighborhoods, which have suffered for half a century because of their proximity to the 6-10 Connector, according to Martina Haggerty, associate director of special projects for the city’s Department of Planning and Development. The connector effectively isolates Federal Hill and the West End from Valley, Olneyville and Silver Lake despite these neighborhoods sharing borders; the connections that do exist, via overpasses and underpasses, aren’t inviting to pedestrians. The neighborhoods have suffered economically and their residents experience negative health impacts because of the connector, she said.

Ian Lockwood, a transportation engineer who focuses on urban design and one of three invited speakers at the recent public meeting, said the 6-10 Connector is designed to allow suburban commuters to access the city or I-95 traveling at high speed, at the expense of the quality of life and air quality of the residents of adjacent neighborhoods.

“There comes a point, from a policy perspective, where it makes sense for the community to have regional commuters driving on (the community’s) terms, and not on some kind of long-distance commute terms,” he said.

Haggerty said a boulevard would reintegrate affected neighborhoods, convert up to 80 acres of state-maintained, right-of-way land into revenue-generating, developable real estate, and improve the overall health of nearby communities.

Boulevard supporters

After decades of delay, funding is finally available to reconstruct the 6-10 Connector. RhodeWorks, RIDOT’s recently approved, 10-year transportation plan, allocates $400 million in state funds to the connector. The project is also eligible for $400 million in matching federal funds, because it will incorporate a bus-rapid-transit route. Furthermore, RIDOT will apply for an additional $100 million in federal grant money available to projects that include pedestrian and bike features and improve disadvantaged neighborhoods.

The allocation of funding has changed the conversation about the 6-10 Connector’s future from theoretical to tangible, and stakeholders have taken note. The city of Providence and the American Planning Association of Rhode Island organized the March 23 public meeting to build support for a multimodal connector that restores connectivity between adjacent neighborhoods.

While not stated explicitly, the remarks of city staff and the homogeneous viewpoints of the three invited presenters imply the city’s preference is a complete replacement of the highway with a boulevard. Event sponsors included environmental groups, neighborhood associations, developers and downtown businesses, each, presumably, with an interest in a boulevard-oriented connector.

The event was attended by about 300 members of the public. Based on their reactions during the presentations and the public comments offered, most favored a multimodal, less-isolating connector.

Expert advice

Peter Park, the former planning director of Milwaukee and Denver, began his presentation with a simple idea: “Remove a highway, improve a city.” Park oversaw the highway-to-boulevard transformation of Milwaukee’s Park East Freeway, and the redevelopment of Denver’s Union Station into the hub of the largest public transit project in the country.

According to Park, it was never the intent of the people who developed the interstate highway system in the mid-20th century for highways to travel through cities. Instead, drivers were intended to exit the highway and access the city via a grid of boulevards that could provide more efficient access to local destinations. While highways limit where people can enter, exit and cross, boulevards allow drivers to enter, exit and cross at logical locations based on their destinations, thus reducing bottlenecks and congestion.

Park said removing highways as a way of improving cities is not a theory. Numerous case studies have proven that a multitude of benefits — place-making, tourism and recreation, development, connectivity — are realized, and that traffic doesn’t metastasis, as is regularly predicted, he said.

“Where do the cars go? They go where they want to go, faster than they did before,” Park said.

He said it’s up to mayors to fight for highway-to-boulevard conversions. Federal and state processes are set up in a way that perpetuate building and rebuilding highways, he said.

“Their process is about mitigating the impact of a highway, more than it is about giving consideration to an alternative,” Park said. “Local leadership is the only way it happens.”

Veronica Vanterpool, executive director of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign and chair of the Bronx River Alliance, spoke about the 19-year struggle of a South Bronx neighborhood demanding the removal of the Sheridan Expressway. The expressway separates residents in the low-income, majority minority neighborhood from waterfront parks on the Bronx River and contributes to the neighborhood’s high rate of asthma.

In the two decades since the New York State Department of Transportation announced its intent to extend the 1.2-mile expressway, advocates of removing the expressway have built a coalition of community members and planning and policy experts, who have worked with local and state leaders to achieve their goal.

In 2001, the state agency agreed to consider removing the expressway. In 2007, it withdrew its plan to extend the expressway. In 2013, New York City endorsed an expressway-to-boulevard proposal, which now resides on Mayor Bill De Blasio’s list of priority projects.

“Don’t be the victims of your transportation network. Be the beneficiaries of it,” Vanterpool said.

Lockwood, the transportation engineer, also advocated for tearing down urban highways. The purpose of cities is to promote efficient social and economic exchanges. Urban highways, he said, decrease efficiency by spreading people and exchanges farther apart.

He cautioned against one form of highway reconstruction: a tunnel or cap. “Capping a highway gives the illusion that you can have it both ways — that you can have great stuff happening on top and have the highway underneath,” Lockwood said. “However, (a cap) still rewards the long trip, creates the parking issues, (requires) ramps — still has the baggage.”

Lockwood said a cap is most common when traffic modelers control the project. Modelers assume that the number of cars using a road will remain the same after a reconstruction project, even if a highway is replaced with a boulevard. Case studies have shown that this isn’t accurate, he noted, and that traffic issues don’t arise because of highway-to-boulevard conversions.

“If the people who believe in modeling control the process, you’re going to get another highway,” Lockwood said. “If people who believe in community control it, then you are going to get a community-friendly outcome.”

He described Boston’s big dig as a project that was controlled by traffic modelers. The resulting cap created several desirable city blocks, he said, but at both ends, the highway comes out of the tunnel and “barfs all over” the surrounding communities.

Missed connection

The overwhelmingly pro-boulevard event left RIDOT director Alviti in the uncomfortable position of being the speaker most hesitant to consider removing the highway. “Coming to you from a place called the Department of Transportation, I feel a little out of sorts with the previous speakers,” he said after taking the stage following the other speakers.

Alviti agreed that the reconstructed 6-10 Connector should be multimodal in nature and offer more connectivity between neighborhoods, but he expressed concerns about the highway-to-boulevard approach. He implied that the connector’s level of service — some 100,000 cars daily — is too high to be accommodated by a boulevard. He also said the railroad tracks adjacent to the connector and the elevation difference between neighborhoods on opposing sides of the highway would continue to make connectivity challenging.

During a panel discussion, Alviti asked the other speakers a question that expressed his concern for suburban commuters. “There (are) competing interests on this project. There are regional interests where commuters from outside the city use (the 6-10 Connector) to pass through Providence rather than connect to local roads,” he said. “When you have regional use that would be displaced or inconvenienced for the sake of the local conveniences that would be afforded through (highway removal), how do you reconcile those two and how do you make provisions to still provide service to the regional users?”

Lockwood’s response further crystallized the differing views of the DOT director and the urbanist experts. He suggested the commuters would have to use an alternative route, such as I-295, to avoid the city. If they elected to pass through the city, it would be on the city’s terms.

“If they decide that they want to live 20 miles away and commute downtown then they need to pay that time tax,” he said. “(City residents) shouldn’t have to pay with their quality of life, health and everything else.”

Commuters receive a “public-social-health subsidy” for living far away from their jobs that people who live near their jobs don’t receive, Lockwood said. The commuter “gets priority in funding, design and space. Why are we spending so much money to reward the problem, when we should be rewarding the solution?”

Put a cap on it

During his presentation, RIDOT director Alviti unveiled early renderings of the agency’s designs for the 6-10 Connector. The renderings show the location where routes 6 and 10 merge between Olneyville and the West End.

In the renderings, the highways enter a tunnel as they merge together and travel along their present-day route under a cap. The cap includes local roads, a bike path and park space. A bus-rapid-transit line is included down the center of the connector and reached by descending into bus stations accessed from the cap.

After the recent meeting, RIDOT deputy director, Peter Garino, explained that initially a cap could be built between Olneyville and the West End and another could be built further north around Dean Street between Federal Hill and Valley. Over time, the space between them could be filled, he said.

The highway is basically maintained in its current form and, therefore, is likely to experience similar congestion. Alviti estimated that the bus-rapid-transit route could have ridership of 10,000 people a day, but the remaining 90,000 cars may be left to sit in traffic in the tunnels leading to the sprawling I-95 interchange.

Lockwood suggests that the reason the connector is congested is because it’s carrying both regional and local traffic. “Do people have to come downtown to get on (I-95), then go 45 miles somewhere else? I don’t think that is the right role of a downtown.”

In his closing remarks, Park emphasized that the 6-10 issue isn’t a technical one, but a political one.

“Engineers are very smart, they figure out all kinds of stuff,” he said, “It’s a question of the criteria that they are designing and engineering to. If it’s just been focused on moving vehicles, than that’s what you’ll get. If it’s about making great cities, strengthening neighborhoods, and connecting people then there is more too it.”

Good summary of the event.

The presentations on situations where highway removal or downgrades lead to much improved city life were inspiring. I’m familiar with examples from San Francisco and Portland OR and it is no exaggeration.

It is disappointing but not surprising that the RIDOT Director (who wants to represent interests of (impatient) suburban drivers as well as the city) plans to keep an expressway. The tunnel idea is his attempt to also take into account the city interests, which I suppose is an improvement from the days (such as when the highway was built) when the DOT took ONLY the motorist interest into account. But the proposed tunnel and green space pictured above with an expressway below, keeping all the land given to the Dean St ramps and such, will be expensive and far from transform the city. The project is still a work in progress, advocates should keep pushing for a better plan.

As for the $400 million busway, it may be "eligible" for "new starts" Federal Transit funds, but that it is competitive and it is far from certain they would award any such funds unless RIDOT/RIPTA can explain the need a busway on Route 6 where there are currently only 7 buses a day weekdays that use it (#9 to Pascoag has 6/day plus one to Scituate) and little potential demand in the area. There are a few more buses using Route 10 but as I recall figuring, even at rush hour a bus on average about every 15 minutes. A real operating plan as to how to use such a busway would be needed. Skepticism is in order for now.

If you don’t want people to drive to work in Providence, they will just take their businesses and tax money to surrounding towns (i.e. Citizens Bank).

If Providence doesn’t want my car flowing through their streets, I don’t want my taxes flowing through their schools.

We are happy to have you driving through our streets, Dan. We are less happy that our streets were destroyed to run highways through our neighborhoods.

Commuters like Dan feel threatened by the boulevard, but I think they’ll find if we build it that it will not only be cheaper, but will be better to drive on.

One of the reasons that Olneyville is constantly congested is that there are few ways through it. Even the folk wisdom that we should "build a flyover" to connect the highway better relies on the idea that people should want to circumnavigate this crunch. But the boulevard greatly reduces the size of bridges– by 80% or more– so that means that we have more room to build a variety of connections in the grid instead of just a few. The flyover plan from the ’90s required knocking down housing, and today’s RIDOT plan for a "610 Dig" like the Big Dig requires capping an expensive highway. Our plan cuts costs, reconnects the options that drivers have, and also adds options for people who don’t want to drive, so that those folks can get out of the way of those who do.

The East Side managed to avoid a highway through it, but imagine an Angell Street Expressway. Wouldn’t that be great? it would make traffic go twice as fast on Angell. The problem is that there are fifteen pairs of lanes going up and down the East Side between Main and Butler, and those lanes carry 30 lanes worth of traffic. They may all be small streets, but they manage the flow. If we built a highway down Angell, only a few of those streets would be open, unless we wanted to spend hundreds of millions reconnecting each additional street. So you’d have 30 lanes of traffic piled onto a few streets (perhaps, Main, Hope, and Gano) and being snarled.

Additionally, we’d have to knock down acres of housing and businesses. Perhaps the whole Thayer Street district. So would this be worth it? And would it help traffic?

No, and that’s why despite the fact that the East Side has many suburban commuters who drive and has some of the largest employment centers in the state, it is not snarled like Olneyville– where almost 50% of residents don’t own a car, and there are no real employment centers for outsiders to visit. Olneyville Square looks like Spring Street in Newport on a summer afternoon, but with none of the economic activity pushing that traffic.

Let’s save. Let’s put back what we save into lower tolls. Let’s build taxable income back into our city.

Stop610Dig

Yes610Blvd

I apologize for my angry reaction. Lets do a real study with real numbers and show if it will work or not. How many cars use the 6/10? How many are local and how many are passing through? What will be the transit time from the Boulevard to Downtown and how many cars can it handle? How else will people get to work and how long will it take? Lockwood says I’ll have to take 295 to 95, which is miles out of my way, but Park says I’ll get to where I have to go faster than before. If you can prove it with numbers, I’ll support it.

I have no transportation expertise, but I will share this personal experience. Every Friday afternoon I drive from Silver Lake to Pawtucket, and it is always faster to drive through the city streets to get to 95 rather than take the 6/10 Connector. My gut tells me that the boulevard will work.

8 months later, the opportunity is missed and the city caved to suburban motorists who care nothing for the city or the neighborhoods, and gave in to basically the same highway system with a few improvements that may be worthwhile but won’t be a game changer.

I think one difference here from the San Francisco example pictured is we have no transit culture as SF does. They extended their streetcar system to the new boulevard and made it part of their real transportation options. Here, and this includes the city, progressive groups, and the environmental community generally, transit is seen mostly as a service for the poor, not a real option for the rest (even though the service is actually better than most non-users think it is) so alternatives to massive auto infrastructure are not on the radar. (same thing with the proposed widening of I-95 north thru the city)