Low Wages Minimize Rhode Island’s Economy

The argument against raising the minimum wage is an argument against the middle class and the local economy

October 29, 2016

Tens of millions of working Americans, from adjunct professors to elderly-care providers to fast-food employees, aren’t paid a living wage. In fact, 26 percent of the U.S. workforce earns less than $10.55 an hour, according to The State of Working America, an ongoing analysis published since 1988 by the Economic Policy Institute.

When the largest U.S. employer, Walmart Stores Inc. — the multinational retailer reported a profit of $120.57 billion in 2015 — holds in-store food drives to help its low-wage employees get through the holiday season, there’s a problem with what many workers are being paid. Yet, when the conservation turns to raising the minimum wage, businesses, mainly of the corporate variety such as Walmart, Dunkin’ Donuts and McDonald’s, lobbyists and chambers of commerce all claim jobs will be lost and the economy ruined.

For instance, predictions of economic doom filled the Rhode Island Statehouse this year during hearings for bills to increase the state’s minimum wage a paltry 50 cents, to $10.10.

“We have raised the minimum wage each of the last four years. Raising it again is not on my agenda for this year,” House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello told the Providence Journal in June.

Ignoring a required, and never mind just, component of any successful economic plan — putting more money in the pockets of workers to spend locally — is another example of what passes for Rhode Island leadership.

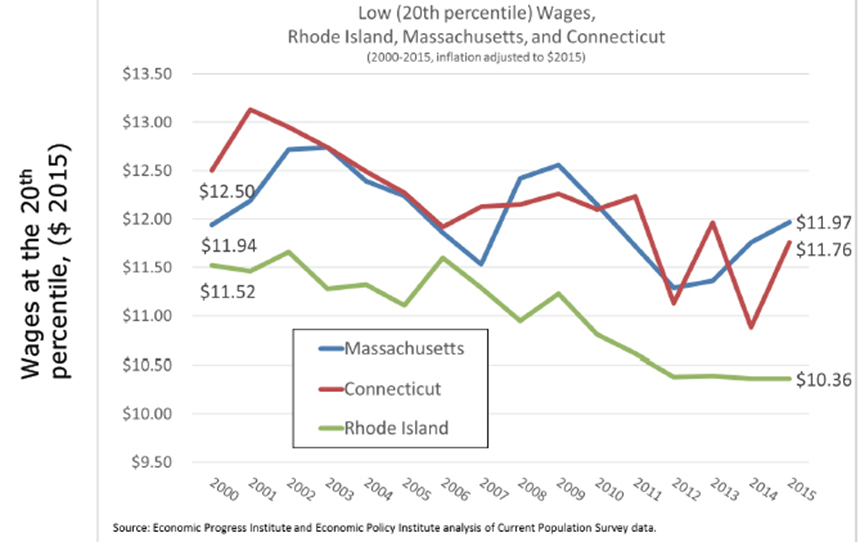

The working poor are a voting bloc that most local politicians aren’t really interested in wooing. Besides, Rhode Island lawmakers threw a few nickels and dimes at income inequality last year, increasing the state’s minimum wage from $9 to its current $9.60.

At the bill’s ceremonial signing in June 2015, Gov. Gina Raimondo said, “We’re going to give a chance to Rhode Islanders who work hard, and it’s just a start, you know. Just even at $9.60, it’s very challenging working full time at $9.60. It’s a huge challenge but it’s a start. It’s a step in the right direction.”

Rhode Island’s working poor must have taken comfort in her use of a cliché to address their real-life situations.

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey has found that about 40,000 Rhode Islander workers are paid the minimum wage. Not all 40,000 are high-school students saving a few bucks for college. Many are adults with families to support. Some of these minimum-wage earners are homeless, and others are living in poverty.

A full-time employee working for the Rhode Island minimum wage, for example, has to work 65 hours a week to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment. Last year, Rhode Island had the highest rate of its residents living in poverty among the six New England states.

Douglas Hall, director of economic and fiscal policy at the Providence-based Economic Progress Institute, told ecoRI News during a recent interview that a “preponderance of evidence” shows that jobs aren’t lost when the minimum wage is increased. He noted the research of John Schmitt at the Center for Economic and Policy Research — Schmitt has said the employment effect of the minimum wage is one of the most studied topics in all of economics — and work done by the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

“Opponents like to tell the story that minimum-wage increases are job killers,” Hall said. “They’ll say its Economics 101. Yeah, but there’s a reason why we study beyond Economics 101.”

In Schmitt’s 2013 report Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?, he examined research going back to 2000 to determine the best current estimates of the impact of increases in the minimum wage on the employment prospects of low-wage workers. He found little or no discernible effect.

“The most likely reason for this outcome is that the cost shock of the minimum wage is small relative to most firms’ overall costs and only modest relative to the wages paid to low-wage workers,” he wrote.

Schmitt also noted that a higher wage reduces reduction in labor turnover, which yields significant cost savings to employers.

Hall said the irony of the ongoing debate is that the companies complaining the loudest about raising the minimum wage — Walmart, McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts, for example — are the ones that would benefit the most if workers were paid more, because those low-wage earners would likely spend more of their increased income at those kinds of businesses.

“What creates jobs is disposable incomes in the pockets of residents,” he said. “The macro effect of raising the minimum wage is taking money from the wealthy and giving it to the less wealthy, who are more likely to spend a greater percentage of it locally. That does more to support the local economy than putting it in the pockets of CEOs and shareholders who are spending their money on Caribbean and European vacations. They’re not necessarily spending that money locally.”

Rhode Island’s economy is inextricably connected to all 1,056,258 of its residents. If unemployment is sharp, wages low, rents high, mortgages underwater and health care unaffordable, then businesses are impacted and the state’s economy suffers.

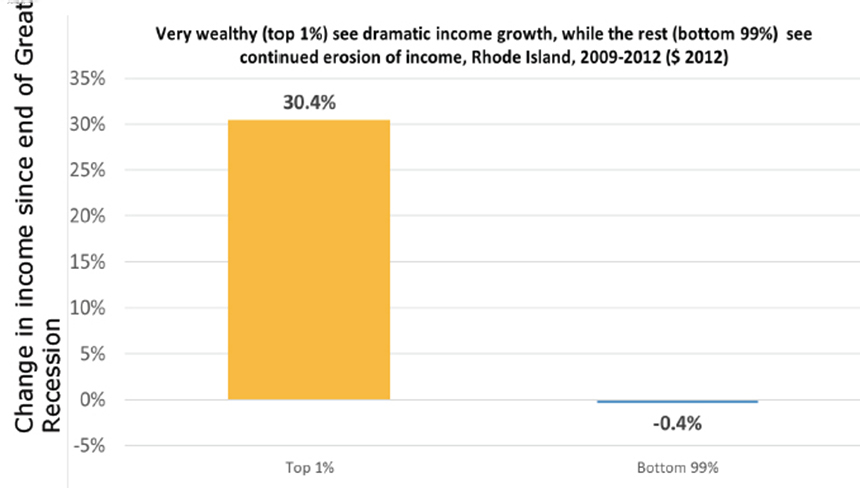

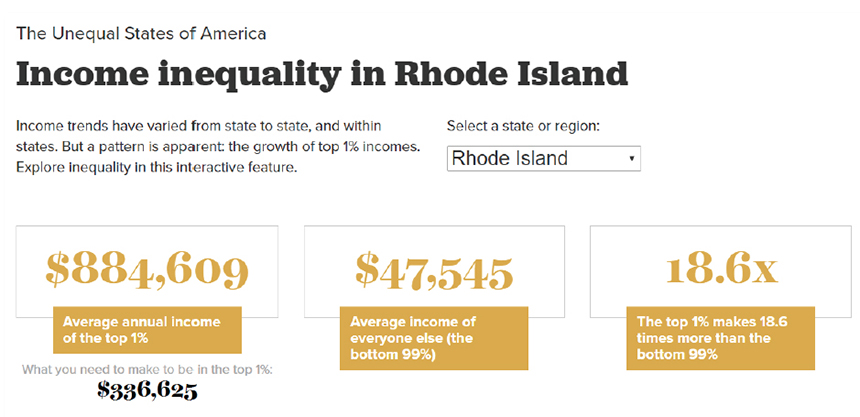

Hall noted that out-of-touch government policies, the weakening of the social safety net, lack of laws supporting collective bargaining, the declining real value of minimum wage, the growing gap between high- and low-wage earners and the consolidation of wealth are weakening both the middle class and local economies.

Rhode Island’s economic development plan, he said, largely ignores these important issues. The state’s continued fascination with using tax deals to lure businesses here from Massachusetts, Connecticut and elsewhere doesn’t make sense or cents, according to Hall.

“We often fail to recognize that unlike license plates economies don’t stop at the border,” Hall said. “Rhode Island has the second-highest share of residents who work outside of the state. We’re part of a regional economy. Luring a company that is 20 miles across the border for 75 to 100 jobs is a losing proposition.”

He said economic development based on a “better-your-neighbor economic approach” is doomed to fail. Hall said Rhode Island would be better served to focus on strengthening its attributes instead struggling to add jobs for the sake of adding jobs.

“Creating an atmosphere of entrepreneurship and tools that would help businesses succeed would pay bigger dividends than tax credits to lure companies in,” Hall said.

However, policies, programs and ideas that would both help society and the economy are largely dismissed or discredited, locally and nationwide. For example, since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted in 2010 more time has been spent trying to destroy the law than correct its flaws.

Despite the law’s needed improvements, the impact it has had on Rhode Island’s most vulnerable is among its biggest successes. Before the law was enacted six years ago, only about 40 percent of the state’s poorest residents were on Medicaid. Today, 85 percent are, thanks to the ACA, according to Eric Hirsch, professor of sociology at Providence College and a member of Rhode Island’s Homeless Bill of Rights Defense Committee.

“Taxpayers save money when people have a primary-care physician,” he said. “It keeps people healthier by catching health problems before they become chronic. Proactive instead of reactive health care keeps costs down and people alive.”

A growing number of low-income households here and across the United States face increasingly unaffordable utility bills, as the cost of living has risen faster than wages. In fact, poorer households are disproportionately impacted by increases in utility prices, as they often pay a far greater percentage of their income for utilities than wealthier consumers.

The loss of utility service because of a household’s inability to pay can lead to severe consequences for individuals, families and taxpayers. People without utility service face eviction, homelessness, illness and the possible suspension of parental rights. Middle-class taxpayers are left to pick up much of that cost, and the economy ultimately takes a hit.

In Rhode Island, if not for the tireless work of the late Henry Shelton, who died in September at his Cranston home, there wouldn’t be an act named in his honor that helps protect low-income residents who owe money to utility companies.

Establishing higher standards for utility shut-offs and better protecting the state’s most-vulnerable residents shouldn’t require a former priest, who in his spare time founded the George Wiley Center, spending decades fighting for justice on behalf of the poor, which also benefits the middle class and the Ocean State’s economy.

Editor’s note: This is the second story in a four-part series looking at homelessness in Rhode Island.

Story 1: Rising Rhode Island Rents Drive Homelessness

Story 3: Providence Cemetery Home Turf for Some People Who Can’t Afford to Live

Story 4: There’s No Place Like a Home to Make Life Better

A low-tax, low-regulation environment enables business growth and hiring. A robust economy creates competition for workers, with a corresponding rise in wages. RI will continue to lose jobs to southern states if it holds to the government-mandated increase in minimum wage as a solution to our weak economy. Companies would simply hire fewer people or leave. Have some common sense.