Land Restoration Helps Revive Polluted Urban River

From the stench of sewage to the sweet smell of success, partnership transforms Acushnet River and former sawmill along its banks into public park

April 2, 2015

NEW BEDFORD, Mass. — The stench emanating from the end of Edward Haskell’s dock on the Acushnet River was so foul that he was compelled to file a lawsuit against the city.

He claimed the large amount of sewage that was accumulating at the end of his dock was causing offensive odors and restricting boat access. He won the case, but 29 years later, in 1899, the problem was no less severe.

On July 15, 1899, the local newspaper, the Morning Mercury, reported that the city’s Board of Health described the Acushnet River as “thick with slime and shores covered with filth from the sewers.” That day’s evening edition, The Evening Standard, reported that the board said bathing in the river was dangerous to health.

This sewage problem also was contaminating shellfish in New Bedford Harbor. From 1900 through 1903, 575 local residents contracted typhoid fever from eating contaminated shellfish, and 93 died. By 1904, the State Board of Health closed the Acushnet River to shellfishing.

The Acushnet River watershed is the most urbanized area in the Buzzards Bay drainage basin, and New Bedford Harbor, the estuarine section of the Achushnet River, is the most contaminated area in the basin, according to a February 2011 report.

The largest of seven rivers that flow into Buzzards Bay, the Acushnet River is routinely ranked in the Buzzards Bay Coalition’s Bay Health Index as one of the most polluted waterways in the bay watershed.

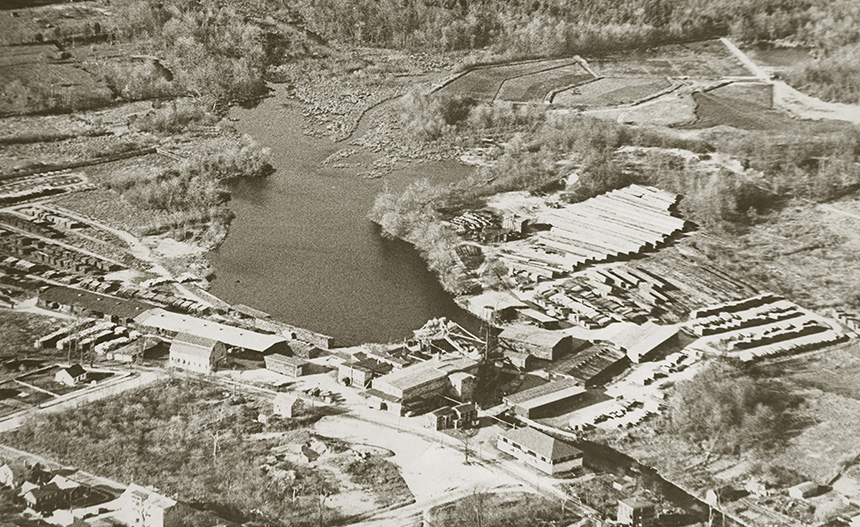

The 8.6-mile river runs through the middle of a 19-acre site just north of New Bedford Harbor that has its own long history of pollution problems. The property, commonly referred to as the Acushnet Sawmill, was a perfect location for a host of industries, from whaling and fishing, to textile manufacturing and metalworking, to tanning and printing. Besides being home to a mill, the property also once housed a roofing company. It was home to some type of industrial use into the 1980s.

Dams were first installed along the Acushnet River circa 1738, cutting off fish passage. The centuries that followed saw the river polluted with sewage, garbage, stormwater runoff, wastewater from bleaching and dyeing processes, heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), combined sewer overflows and fertilizers.

“Humans don’t always take very good care of natural resources,” Sara N. da Silva Quintal, restoration ecologist for the Buzzards Bay Coalition (BBC), said during a March 25 event at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Quintal spoke about the coalition’s Acushnet River restoration project, and how, through dam removal, riverbank reconstruction, invasive plant management and land restoration, the urban river’s herring population has increased dramatically. She also detailed how the BBC and its partners are transforming the derelict lumber yard and abandoned industrial complex into a park scheduled to open to the public by this summer.

Since 2007, when the BBC bought the property, work has been ongoing to remove the remains of the former sawmill. This restoration project also will improve the health of the river and Buzzards Bay, and make it easier for migratory species such as river herring and American eels to travel back and forth between the ocean and upriver spawning and nursery areas.

When the BBC took possession of the neglected property, it was overgrown with weeds and had become an eyesore to neighbors along Mill Road. Decaying buildings sat on acres of cracked pavement, sending polluted runoff into the Acushnet River every time it rained. It took the BBC a full year to get all the necessary local and state permitting.

One of the project’s partners, the city of New Bedford, removed the asphalt to make way for a wildflower meadow and a red maple swamp. All of the property’s buildings, with the exception of one that was salvaged, were razed. Granite blocks taken from the deconstruction of river walls were reused as amphitheater seating. Lumber from the invasive trees that were cut down was used to make boardwalks and lookouts, which local high-school students helped build.

Along the river’s bank, native plants and trees have replaced the broken concrete and granite slabs that unnaturally channeled the river’s water. Natural areas again, these spaces will now filter and absorb pollution instead of sending it straight into the river. Floodplains have been restored, and a canoe launch built.

The restored meadow and wetlands also will provide habitat for birds, foxes, turtles and other wildlife. Since work began eight years ago, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries has recorded a 16-fold increase in the number of herring in the Acushnet River. Last April, 10,144 herring were counted in the Acushnet River, according to the BBC.

“We want to bring people back to the river to enjoy it,” Quintal said. “They haven’t been able to get up close and personal with the river for a long time because of the pollution.”

The Acushnet River restoration project has been funded primarily by the New Bedford Harbor Trustee Council. This project is one of 34 the council has supported throughout New Bedford Harbor as part of a $20.4 million settlement with companies that polluted the harbor.

It’s a nice story but it’s mostly bullshit. What article misses is that this part of the river wasn’t and isn’t urban or polluted. This writer and the Coalition for Buzzards Bay doesn’t know or doesn’t care kids and adults used this pond (about two miles upstream and above a waterfall) for all sorts of things throughout the 50’s, 60s and 70’s. It became used less when Joe England bought the surrounding property and made a mess out of trails with dirt bikes. The writer and CBB would do well to talk to the people and families that actually live in the surrounding area.