Concerns About Corporate Takeover of Water Supply Overflow

Opponents of the sale or lease of Providence Water say the goal of a public water supply should be clean drinking water, not closing budget gaps

April 1, 2019

PROVIDENCE — Opponents of privatizing Rhode Island’s largest public water supply to cover pension obligations say selling or leasing the public water source represents the same kind of shortsighted thinking that created the city’s pension crisis.

Monetizing — as Mayor Jorge Elorza likes to call the idea — Providence Water and its source, the Scituate Reservoir, would largely shift the financial burden of funding the city’s pension responsibilities onto those who can least afford it. It also would push that responsibility onto ratepayers who don’t even live in Providence, as all Providence Water customers would face the same inevitable rate increases.

Providence’s pension problem was created by previous mayors and local officials, most notably the late Buddy Cianci, who routinely underfunded the city’s pension liability. According to estimates, only about a third of the city’s estimated $1 billion pension obligation is currently funded. Under the state standard, a pension system that is less than 60 percent funded is considered to be in “critical condition.”

Elorza has called the Providence Water system and its accompanying real estate, some 13,000 acres, a “significant asset.” He has publicly stated that it’s worth somewhere between $300 million and $700 million, depending on the number of restrictions included in any enabling legislation. The system’s value increases with fewer restrictions.

He has said Providence should be allowed to generate a profit on the water supply it controls. His current plan proposes a long-term lease of the system, and he has mentioned the possibility of such a deal with the quasi-public Narragansett Bay Commission. The enabling legislation (H5390 and S0324), however, allows for any type of “transaction.”

Since 2017, Elorza has been touting the sale or lease of Providence Water as the best way to pay down the city’s unfunded pension liability.

Late last year, the mayor told WPRI, “There are no other assets. If there was another option out there, you would think that either my administration, [Angel] Taveras’s administration, [David] Cicilline’s administration, would have identified it by now. That easy option, that easy alternative, is just not out there.”

On March 25 in a Providence middle-school auditorium — the last of three public presentations conducted by the mayor’s staff — city officials laid out their argument for leveraging the municipal water system to fund the pension system. However, they largely ignored the many documented problems created when corporate interests take control of a public utility like drinking water.

“All of these deals are the same. They all work out in the same terrible way,” said Gillian Kiley, an opponent of privatization who attended last week’s presentation. “There are characteristics of these deals that are consistent from city to city … the water quality suffers; the infrastructure suffers; environmental regulations are ignored; labor gets cut usually by about a third; the cities never get the money that they want, and the rates always go up. The corporations know exactly how to get around any promises they make. They’re resourced to do so, and it’s their job to do it. Their mission is not to protect the water. Their mission is to make money.”

Private problems

Opponents of the mayor’s privatization idea have all drawn comparisons to Flint, Mich., and other municipalities that have suffered from privatizing public water systems.

In fact, the four corporations that responded to Elorza’s request for qualifications — Veolia, Aquarion, and a joint bid by Poseidon Water and SUEZ North America — have questionable track records that include misuse of chemicals, boil-water advisories, an increase of lead in drinking water, lawsuits, and broken promises.

Elorza’s privatization plan faces opposition from City Council members, mayors of neighboring municipalities, the state treasurer, who has questioned whether Providence even owns the system, and environmental and social justice organizations.

The Conservation Law Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, the Rhode Island Land Trust Council, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island, the Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe and other indigenous groups, and the Land and Water Sovereignty Campaign, which was organized late last year, have all raised concerns about changing ownership of the water system.

Kiley, a member of the Land and Water Sovereignty Campaign, said the city can’t solve decades of financial mismanagement by placing much of the state’s drinking-water apparatus in private hands. She said Rhode Island shouldn’t trust that an out-of-state private entity will protect the interests of Rhode Islanders.

ecoRI News recently meet with Kiley and two other Land and Water Sovereignty Campaign members, Cristina Cabrera and Kate Schapira, to discuss their concerns about privatizing Providence Water.

Should Providence Water be privatized, Schapira is concerned stewardship of the natural resource would be compromised and Rhode Island’s entire drinking-water supply would become vulnerable to a corporate takeover.

“People who are most likely to be injured by this deal are people who have expertise on what happens when life-sustaining resources are commodified, because they have already been on the receiving end of similar deals,” Schapira said.

Cabrera noted that water isn’t a corporate asset for shareholder benefit. She said the current enabling legislation better protects corporations than the water supply and the public.

“The city’s fiscal issues are separate from the water issue,” she said. “We need to protect our water from corporate America.”

The three women said such a move would threaten open-space land buffers and risk polluting the watershed, the Providence Water supply, and private wells. They noted that the legislation also would allow the sale or lease of any municipal water system in Rhode Island to a corporation or investment firm.

Kiley said city officials are “just talking about the pension, the pension, the pension … they don’t include the people who will be hurt the most by this.”

The Municipal Water Supply Systems Transactions Act would strip authority away from state agencies and place water-system decisions solely in the hands of for-profit entities. “(N)either the Rhode Island public utilities commission nor the Rhode Island division of public utilities and carriers shall have any jurisdiction, authority, or other power to approve, reject, review, or in any way affect any transaction,” according to the House bill sponsored by Reps. Scott Slater, Raymond Hull, Joseph Almeida, and Grace Diaz, all Providence Democrats.

All three Land and Water Sovereignty Campaign members said the goal of a public water supply should be clean drinking water, not closing budget gaps.

They say there is no evidence that privatized water systems are superior to public ones in terms of safety and water quality. In fact, there are plenty of examples of water systems being run poorly in the hands of private interests. The Flint tragedy is the most notable, but water privatization problems also have been documented in Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and Rockland and Gloucester, Mass.

“If I were from Nestlé, and I looked at this legislation, I would celebrate,” Kiley said. “Rhode Island is next. Let’s go mine some water, because it’s like a wishlist for a corporation. It opens the door to incredible exploitation.”

The women said the Land and Water Sovereignty Campaign has filed 10 Freedom of Information Act requests with the city for more information about the bidders. All have been denied, they said.

Bad deals

Veolia, a French transnational company with activities in service and utility areas traditionally managed by public authorities, such as water management, was sued in 2016 by the Michigan attorney general for the role the company played in the Flint water crisis.

The initial elevation of lead levels in Flint water was traced back to the city’s decision to switch its water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River, which occurred before the city hired Veolia. The AG’s lawsuit, however, charged the company with “professional negligence and fraud, which caused Flint’s lead poisoning problem to continue and worsen, and created an ongoing public nuisance.”

Veolia published a report at the height of the Flint lead crisis, stating that the city’s water was safe to drink.

At around the same time, the city of Pittsburgh was also witnessing a higher level of lead in its drinking water. Veolia had a contract managing the city’s water system, but in 2016 the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA) sued the company, charging that “Veolia grossly mismanaged PWSA’s operations, abused its positions of special trust and confidence, and misled and deceived PWSA.”

Pennsylvania’s attorney general has since sued the PWSA for violating the state’s Safe Drinking Water Act multiple times. In response to the AG’s recent action, the Our Water Campaign asked why Josh Shapiro is “only focusing on the authority that was left to pick up the pieces after a failed privatization contract, instead of the corporation — with a disastrous track record — that managed the authority when the lead crisis was triggered?”

Three years into a 20-year deal Indianapolis signed with Veolia, officials began investigating the safety of the city’s water supply. Veolia mismanagement had caused a boil-water advisory for more than a million people, closed business, and canceled school. The city eventually paid Veolia $29 million to terminate the agreement early.

In 2004, Rockland, Mass., canceled a contract with Veolia for the operation of its wastewater treatment plant, after state officials found the agreement may have been illegally tailored to help the company. And last April, Veolia, which manages Plymouth’s water-treatment plant, agreed to pay $1.6 million to settle allegations that it allowed thousands of gallons of contaminated wastewater to spill into Plymouth Harbor and millions of gallons of raw sewage to flood parts of town. Despite the settlement, the company blamed the spills on the town.

In 2003, Atlanta dissolved its 20-year contract with United Water — now known as SUEZ North America — after four years of terrible service that included cutting the workforce in half, a maintenance backlog of more than 13,000 work orders, and corruption.

In 2009, after bacterial contamination forced residents and businesses to boil their water for nearly three weeks, the city of Gloucester, Mass., decided against renewing SUEZ’s contract.

Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that focuses on corporate and government accountability relating to food, water, and corporate overreach, has published reports that document the water-system problems of Veolia and SUEZ.

In Hingham, Mass., local officials and representatives of Aquarion, a privately operated subsidiary of Eversource, have spent the past three months fighting over the future of the town’s water system.

Hingham officials believe they can operate the system better than Aquarion and are seeking to force the company to sell it under a provision of the 1879 law that first privatized the town’s municipal water infrastructure, according to a Feb. 4 story in The Patriot Ledger.

Aquarion has spent some $2 million on marketing to keep control of the water system. Selectwoman Mary Power told the newspaper, “I wish Aquarion spent as much money replacing the water mains as they do on public relations efforts.”

This month, Town Meeting voters are expected to decide who takes control of their water system.

Boston-based Poseidon Water is a leading seawater desalination developer — a controversial method for creating fresh water that takes in and destroys marine habitat by killing fish, invertebrates, fish eggs, plankton, and larvae and discharges a byproduct of concentrated salt and harmful chemicals.

Expensive water

Activists and environmental groups have noted that privatization typically increases water rates, because the corporations supplying the water are obligated to generate a profit for their shareholders.

Food & Water Watch has found that corporations have “consistently raised customers’ rates after taking control of public systems — often making water unaffordable to the poor.” It also has noted that profits are funneled away from maintenance and infrastructure upgrades and into the pockets of distant shareholders and corporate executives.

National data compiled by the D.C.-based organization found that privately owned water companies charge 58 percent more, on average, than public utilities do, and rates of privately owned companies have increased on average at three times the rate of inflation. Private sewer service can cost as much as 80 percent more than public service, according to Food & Water Watch.

A 2016 Food & Water Watch survey found that water systems are publicly owned and operated in the 10 most affordable cities for water of the 500 systems surveyed. As of January 2015, Phoenix, Ariz., had the most affordable household water use, while Flint “was the most expensive — an anomaly given the problems that the city has faced under emergency management.”

Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization, has published research in opposition to water privatization, claiming that privatization leads to rate increases, undermines water quality, decreases access to water for the poorest residents, and creates a lack of accountability.

Hostile takeover

The Scituate Reservoir was created more than a century ago by displacing indigenous people and local residents and razing some 1,200 buildings and homes. It’s a story of eminent domain and the state’s use of force. The story began in 1915, when the General Assembly approved the state’s largest public works project in history: level and flood five villages in the town of Scituate to build a reservoir to provide drinking water for Providence residents.

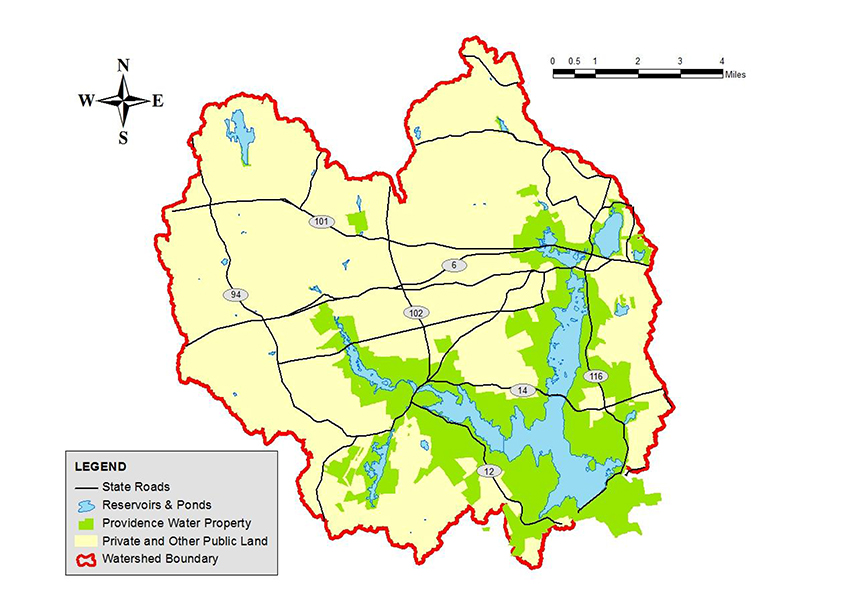

Today the Scituate Reservoir provides water to 60 percent of the state’s population. It holds nearly 40 billion gallons of water. Its watershed is primarily within the rural towns of Scituate, Foster, and Glocester. The total drainage area covers 93 square miles or nearly 60,000 acres.

Don’t let the fox guard the hen house – the farmer (Providence and the State of RI) barely do their job. Water is life. It should be a top priority to insure its purity and availability to all.